Earlier this year, Sen. Elizabeth Warren proposed a federal wealth tax on a handful of U.S. households with the highest net worth. Sen. Bernie Sanders has just announced his own wealth tax proposal, which is similar to Warren’s. A few other presidential candidates say they support the concept although they have not provided any details.

The following draws from the report ITEP published in January on the potential for a federal wealth tax and on the details of Warren and Sanders’ plans.

Why would a federal wealth tax be different from the tax policies we already have?

The federal tax system mostly taxes income, not wealth. When an individual’s income takes the form of wages, it is subject to the federal personal income tax and federal payroll taxes. When income is generated from wealth, such as dividends paid on corporate stocks or capital gains generated by selling assets, it is also subject to the federal personal income tax (although, unfortunately, at lower rates). When income is generated by a corporation, it is subject to the federal corporate income tax. But there is no federal tax on the wealth itself—on assets such as corporate stocks, other business interests, real estate or other types of wealth.

The only partial exception is the federal estate tax, which is like a wealth tax except it is only imposed on individuals’ wealth at the end of their lives. And, technically, the estate tax is imposed on the transfer of wealth rather than wealth itself. Warren and Sanders are proposing an annual tax on the net worth of very wealthy individuals—a federal tax directly on wealth—to strengthen our tax system.

What are the goals of proposals for a federal wealth tax?

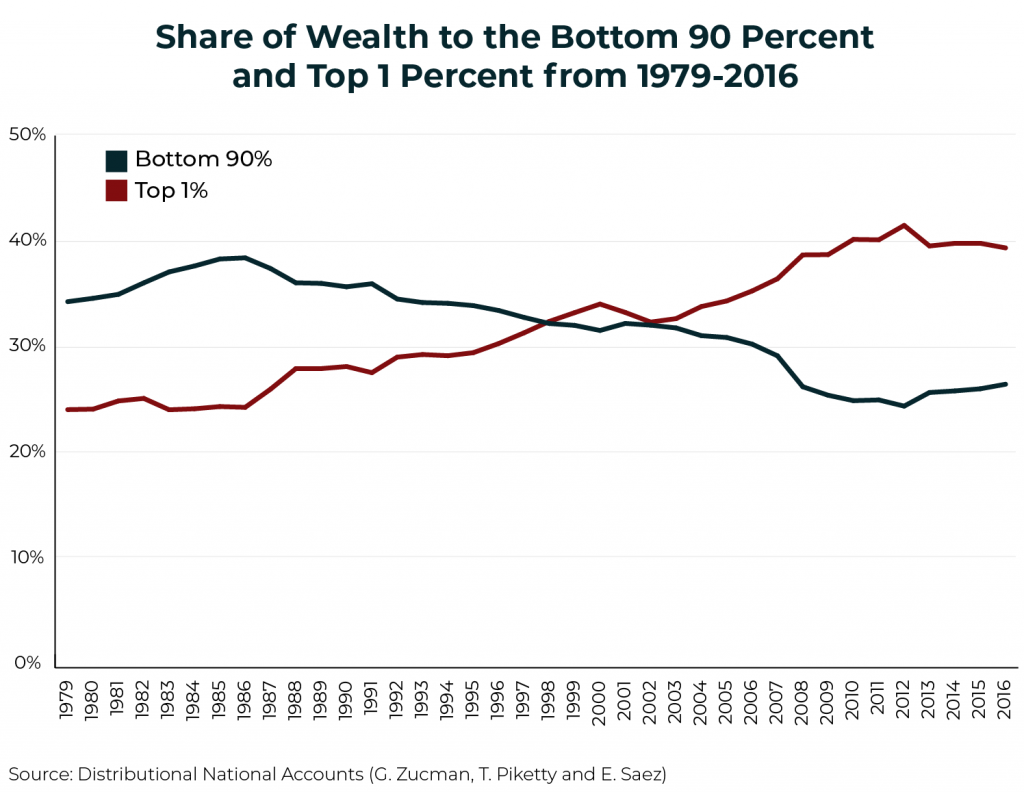

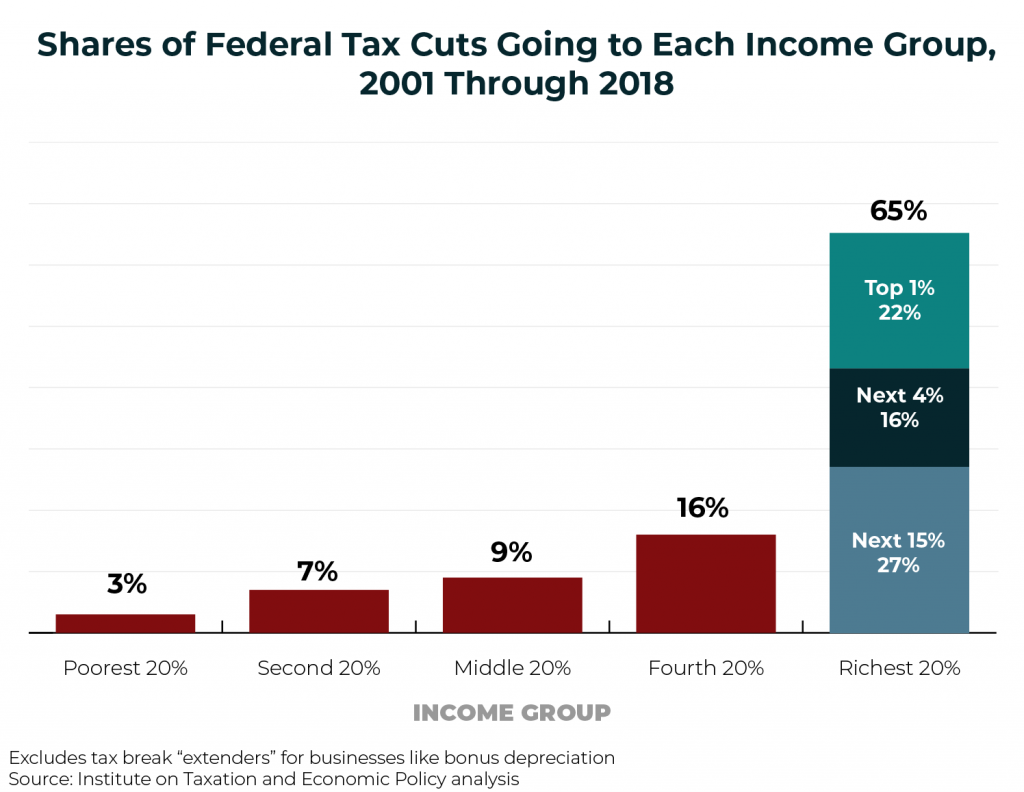

A federal wealth tax would raise revenue to make public investments and curb growing inequality among Americans.

The federal government currently is not collecting enough revenue to make the types of investments that are typical and needed in developed nations. The nation’s tax code is not particularly progressive, even though most Americans say they support progressive taxes. A federal wealth tax could help address both problems.

How would a federal wealth tax improve our tax system?

Federal income taxes as currently structured do not address the ways that very wealthy people accumulate vast fortunes largely tax-free. A middle-income person with a savings account pays income taxes on the interest it generates each year, which over time reduces how much savings can build. But a wealthy person who owns an asset that appreciates each year does not pay income tax until she sells the asset, which allows her wealth to build much more rapidly and substantially over time.

One way to address this problem is to tax wealth directly, as Warren and Sanders propose. Their plans would create a federal tax calculated as a percentage of individuals’ or households’ net worth rather than calculated as a percentage of their income.

Are there other ways to address the same problems?

Another approach to address this is reforming the income tax so that wealthy individuals’ untaxed asset appreciation, their “unrealized” capital gains, would be counted as taxable income. Sen. Ron Wyden, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee, as well as some presidential candidates, have proposed this approach, known as mark-to-market or anti-deferral accounting. These proposals would also do away with the special, lower income tax rates that apply to capital gains income.

Proposals to fundamentally reform how the federal government taxes capital gains income and proposals to tax wealth all are designed to solve the same problem—the ability of the extremely rich to accumulate wealth more rapidly, and with fewer roadblocks, than the rest of us.

Who would pay a federal wealth tax?

Sanders’ wealth tax would only apply to net worth of married couples in excess of $32 million (half that amount for unmarried individuals). This means that a couple with a net worth of $32.5 million would only pay the tax on the $500,000 in wealth that exceeds the threshold.

ITEP’s report concluded that a household would need to have a net worth of roughly $32 million to be among the top 0.1 percent of households in 2020.

Warren’s proposal would apply only to net worth in excess of $50 million, meaning it would apply to an even smaller group.

How much would people pay?

Warren’s proposal would annually tax net worth in excess of $50 million at 2 percent and would add another 1 percent for net worth in excess of $1 billion. Warren’s wealth tax would effectively have two tax rates, 2 percent and 3 percent.

Sanders’ wealth tax would apply at a rate of 1 percent for net worth between $32 million and $50 million and would have progressive rates, each one percentage point higher than the last, until reaching 8 percent for net worth in excess of $10 billion.

Would the wealthy find ways to avoid the wealth tax?

No tax is effective if it is not enforced. One should assume that a president and Congress willing to enact a federal wealth tax would be willing to fund enforcement by the I.R.S. and make reasonable efforts to reduce avoidance. Both Warren and Sanders call for an increase in the I.R.S. enforcement budget to implement the tax. Both would set a minimum audit rate for those subject to the wealth tax. Sanders would require that all billionaires are audited annually.

Both Warren and Sanders also would impose an exit tax on the wealth of anyone who attempts to renounce their U.S. citizenship to avoid the wealth tax. Both propose an exit tax equal to 40 percent of net worth above a high threshold. Sanders’ exit tax would rise to 60 percent of net worth exceeding $1 billion.

It is true that wealthy Americans who do not attempt to leave the United States or give up their citizenship could still try to hide assets offshore. But as ITEP’s report explains, Congress has given the I.R.S. more tools in recent years to track down offshore assets, including the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), which requires taxpayers living in the United States to file information about offshore assets with their federal income tax returns if those assets exceed $50,000 in the case of singles or $100,000 in the case of married couples.

Why do some people say a federal wealth tax would be unconstitutional?

Opponents of a federal wealth tax would certainly challenge it in court if enacted. Some believe they have a case that it would violate the U.S. Constitution. They point to constitutional provisions limiting Congress’s power to impose “direct” taxes. These antiquated provisions were adopted to limit federal taxes that southern taxpayers might have to pay on their slaves and on their land. But even at the time of the Constitution’s drafting, no one knew what taxes might qualify as “direct.”

Many scholars today point out that the “direct tax” clauses were part of a compromise allowing slavery and the very different context in which we live today should lead us to a very narrow interpretation of these provisions.

And in fact, this is what the Supreme Court did for most of its history. But a couple of Supreme Court decisions veered sharply away from this tradition of deference to Congress’s taxing powers, most notably the 1895 decision that struck down a federal income tax and lead to ratification of the 16th Amendment to overturn its result. The 1895 decision was considered incorrect by many scholars even when it was rendered and it has since been eroded by subsequent decisions.

For more information, see ITEP’s federal wealth tax report.