The third stimulus package—the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act—was deeply flawed. It did not have to be this way. Yes, the COVID-19 crisis forced Congress to act quickly. But lawmakers could have ensured better targeted and better timed relief if our system of social supports did more through automatic stabilizers for the economy, meaning they take effect, or ramp up, as soon as the economy deteriorates, resulting in government spending that pumps money into the economy even in the absence of any legislative action.

With adequate automatic stabilizers, the United States might not end up with economic relief bills that have provisions tucked in them mostly helping millionaires, as we learned was the case with a CARES Act provision suspending limits on business losses. And regular people could get help more quickly, blunting the economic downturn.

Why Automatic Stabilizers Are Better

The United States has some automatic stabilizers in place, but they are limited and insufficient. For example, during a recession, more unemployment insurance (U.I.) benefits are paid out simply because more people are unemployed, and this increased U.I. spending partly offsets the drop in consumer demand that would otherwise occur. But U.I. is structured to allow state programs to run out of funds during a recession unless Congress provides federal support to prop them up.

A stronger U.I. system is just one example of how the United States could have protected people and the economy more effectively. Providing automatic cash payments to households is another. The cash payments provided by the CARES Act (which are usually described as tax rebates) provide important relief, but they could be even more effective if Congress had already taken the time to enact them as a program that kicks in automatically when triggered by certain economic indicators. As it was, it took several weeks for payments to start arriving, and many people are still waiting.

A variety of proposals could automatize relief during times of economic turmoil ranging from creating new programs to expanding existing ones (see research from the Economic Policy Institute and Washington Center for Equitable Growth, among others). Advance planning can target relief to populations in most acute need and ensure that help is not held hostage by time-consuming political wrangling ahead of economic downturns. Just as importantly, automatizing temporary expansions in social programs can ensure that lawmakers aren’t pressured into pumping the brakes on those programs too early during the economic recovery. In 2013, for example, more than one million unemployed people who had been looking for work for more than six months were cut off from the Emergency Unemployment Compensation program, even as the unemployment rate remained elevated at 6.7 percent.

What We Got Instead of Automatic Stabilizers

Unfortunately, as people face the current crisis, Congress has rushed to draft several relief packages with little time for analysis and even less ability for the public to understand what was being enacted.

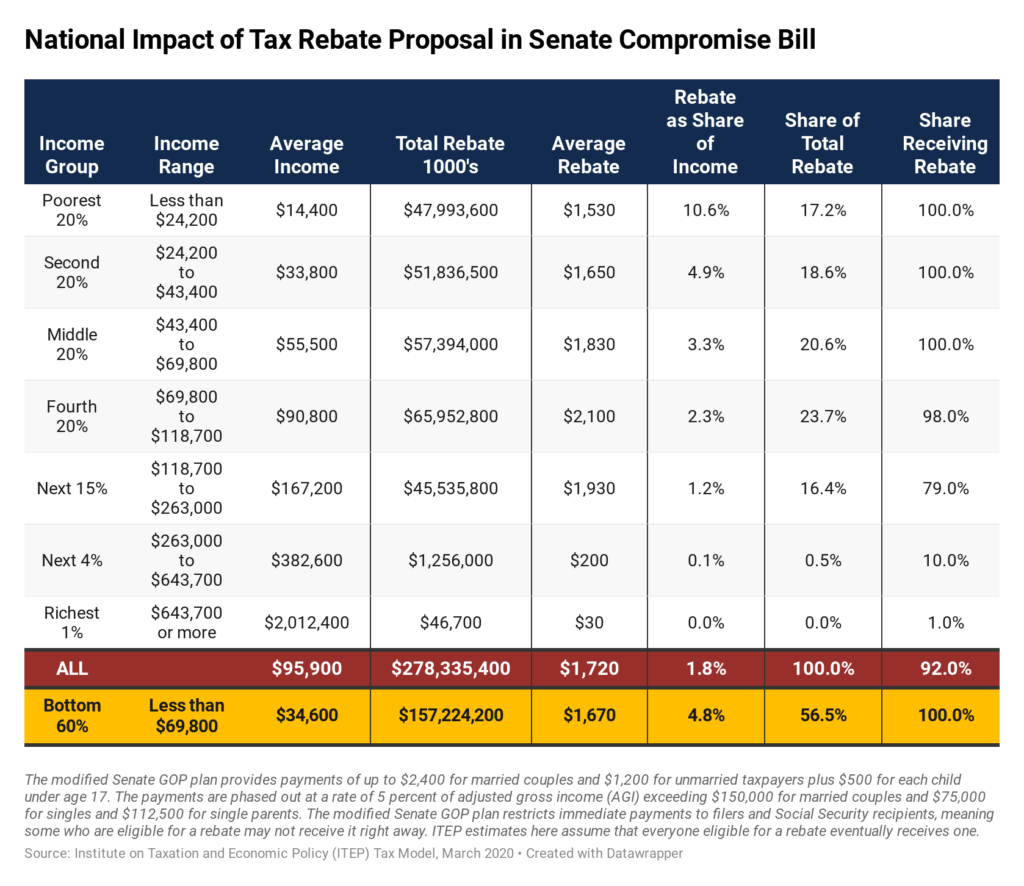

The results speak for themselves. A handful of the CARES Act’s most generous concessions to business overwhelmingly benefit the highest-income tax filers. For example, the CARES Act substantially changed rules related to business losses. A suspension of limits on excess business losses is estimated to channel almost 82 percent of its benefits to those making more than $1 million annually in 2020. On average, those benefiting are expected to receive a windfall of more than $661,500, hundreds of times larger than the modest $1,720 average payment going to working families.

Provisions changing loss rules could cost a combined $195 billion over the next decade—more than the rescue package spends on aid to hospitals and healthcare providers or direct assistance to state and local governments. The scope of these modifications can scarcely be tied to the type of economic relief that workers and small businesses could benefit from, and the widespread gaming these types of changes incentivize are overwhelmingly enjoyed by the wealthiest and most powerful.

The disappointment many feel about these last-minute provisions is not an indictment of the widely-agreed upon need for stimulus spending—instead, it shines a harsh light on the realities of crisis-driven budgeting.

Decades of underfunding of social protection programs and deliberate attempts to bureaucratically disentitle populations by creating byzantine processes for filing benefit claims has meant many working people are struggling to find relief. Additionally, down-to-the-wire negotiations left several notable Easter eggs for advocates and the public to discover and attempt to address after the fact—and this within recent memory of the largest tax package in a generation sailing through Congress before many lawmakers had time to read the 479-page bill.

As frustrations about the on-going push for additional stimulus relief grow, opportunities to expand automatic stabilizers for now and the future ripen. This crisis has exposed decades-long cracks in our economic system which have exacerbated inequalities and reduced the resilience of the working families. We can’t avoid the next downturn. What Congress can do is ensure adequate relief to families from which to negotiate upwards. And we can minimize the opportunities for poorly-targeted giveaways. Those two things would ensure that individuals and families suffer less, and that economic resources are targeted where they’ll do most to spur recovery.