By Meg Wiehe and Carl Davis

A recent editorial in the Wall Street Journal and an opinion piece in the New York Times are both helpful in making the case for taxing the rich and providing more federal aid to individuals and states.

The Wall Street Journal noted that states ended their fiscal years in a better space than estimated when the crisis first took hold (though notably still lower than had there been no pandemic) in part because of a “rebound in equities and boom in tech stocks.” In other words, because the rich have managed to get richer even during these trying times.

Conspicuously absent from the editorial, however, is any discussion of the $2.2 trillion CARES Act enacted in March that put money in poor, moderate- and middle-income people’s pockets after the bottom fell out of the economy. The $1,200 payments to individuals as well as the weekly $600 federal boost to unemployment benefits allowed those who have no money in the stock market to continue to stimulate their local economies by paying for their basic needs and other goods and services. The Paycheck Protection Program also prevented even more job loss and allowed people to economically stay afloat.

But now that well has dried, and GOP leaders have made it clear that they oppose another robust stimulus package that would help people, communities, and state and local governments. Absent federal aid, state and local revenues will further plummet and policymakers will have to step up to ensure they have the revenue they need to avoid critical service cuts. Case in point, Michigan’s latest consensus revenue forecast released last week acknowledges the positive role the initial federal assistance played in staving off a larger revenue crisis for now (though revenues are still down), but also cites the lack of additional federal aid with a “precipitous drop in revenues for fiscal year 2021.”

In the New York Times, Kitty Richards and Joseph Stiglitz wrote, “In a recession, [state and local] cuts also damage the broader economy, causing layoffs to ripple through the community… Tax increases, especially on high-income people who aren’t living paycheck to paycheck, are much less economically damaging, costing the economy only around 35 cents for every dollar raised. States and localities that raise taxes on the rich to increase spending will create at least $1.15 of economic activity for every dollar raised, and most likely closer to $2.15 or more.”

Reductions in critical state and local investments, including health care and education, would only exacerbate the economic crisis brought on by COVID-19 and worsen racial and income inequality for years to come. Higher taxes on top earners are among the best options for addressing pandemic-related state revenue shortfalls in the coming months.

Some States Are Taking the Lead

In the absence of federal leadership, lawmakers and advocates in a number of states are taking the lead on proposing or promoting tax increases on the rich to stave off deep and devastating budget cuts and allow for much needed new investments.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy re-upped his commitment to taxing Garden State millionaires in a budget plan unveiled last week. He also has voiced support for a tax on high volume trades known as a financial transaction tax. By asking the state’s wealthiest residents to pay their fair share, the plan would protect and expand much-needed investments in education and health care. Gov. Murphy also understands that raising revenue is a surer and more equitable path to recovery for all New Jersey residents than relying on deep spending cuts to balance the state’s budget.

Lawmakers in California, New York, and Rhode Island have also proposed higher taxes on their state’s wealthiest residents to help close their pandemic shortfalls and redress longstanding adequacy and equity issues in their tax codes. Proposals range from raising personal income tax rates on their highest earners to new taxes on net worth and second homes. Advocates in those states have also formed broad coalitions to promote higher taxes on the rich including the Commit to Equity coalition in California, Strong Economy for All in New York, and Revenue for Rhode Island.

Voters in Illinois and Arizona will have an opportunity to directly approve higher taxes on their state’s richest residents this November. Both initiatives were underway pre-COVID but are well-timed to deliver significant new revenue to fund current and long-term investments.

Five Things to Know About Taxing the Rich

Taxing top earners is among the best options for bolstering low state revenues because, by definition, top earners are best situated to afford to pay more. It’s also the most efficient way to raise the amount of revenue needed to meet the challenges brought on by the pandemic. Here are five things to know about this policy option:

- High-income taxpayers have fared comparatively well during this crisis. College-educated and higher-earning households are less likely to have been laid off as a result of the pandemic and its economic fallout. Many of these households have also seen their stock portfolios benefit from the rapid rebound in the stock market. And many top earners have seen their disposable incomes increase as they have cut back steeply on spending at restaurants and on personal services. While some top earners have no doubt faced income losses due to this crisis, those taxpayers will not be affected by targeted increases in top tax rates unless they still managed to reap large incomes during the pandemic. Only those households managing to earn high incomes in 2020 or 2021 (depending on the effective date of the legislation) would be asked to pay more under a new top tax bracket, for instance.

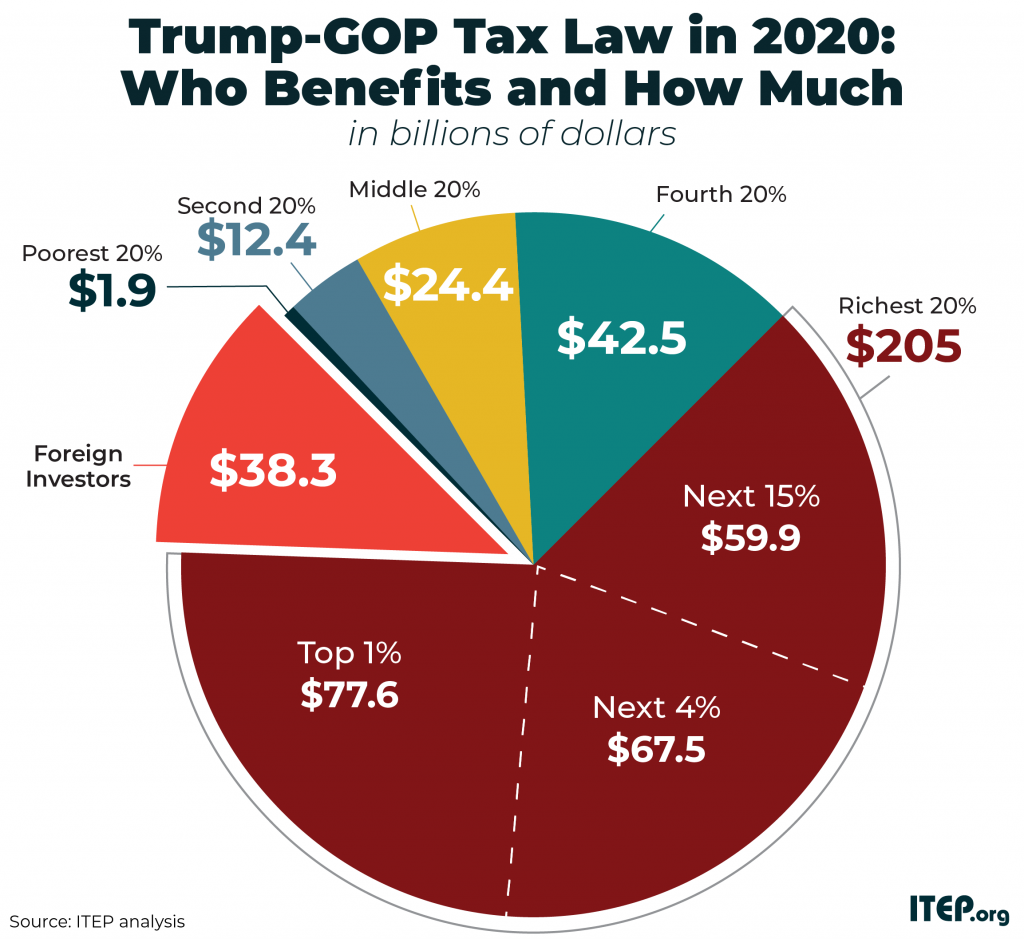

- Top earners are paying less tax now than before. In December 2017, Congress and President Trump enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) which cut taxes on the top 5 percent of earners by an astonishing $145 billion this year alone. The nation’s most affluent 1 percent of taxpayers–those earning over $639,000 per year–can expect to receive an average tax cut of nearly $50,000 in 2020. On top of those cuts, top earners have also contributed less to state and local coffers via the sales tax in recent months as they have cut back on spending more dramatically than families of more modest means. Clawing back some of the tax cuts received by top earners in recent months and years is a logical way to begin addressing state revenue shortfalls.

- High-income taxpayers pay the lowest state and local tax rates. When income, property, and consumption taxes are viewed as a package, the vast majority of states ask less of top earners than of either poor or middle-income taxpayers. That is, states tend to levy the lowest effective tax rates on those taxpayers with the highest incomes. Boosting taxes on top earners is an appropriate step toward remedying this inequity during normal times and is even more urgent during times of crisis when ordinary families are facing economic hardship and state and local governments are confronting clear and immediate revenue needs.

- Raising taxes on top earners is a proven strategy for addressing state revenue shortfalls in economic downturns and was a common response by states to the Great Recession. Most states raised taxes during the last recession and a diverse group of states including, but not limited to, Maryland, New York, North Carolina, and Wisconsin opted to raise top income tax rates. Lawmakers in these states understood that, in times of budgetary and economic crisis, asking more of families with high incomes is far less painful than cutting essential services, weakening the safety net, or raising taxes on families of more modest means who are bearing the brunt of the economic downturn.

- Voters want to see taxes raised on top earners and corporations. Roughly two-thirds of Americans think that upper-income families and corporations pay too little in tax and have made that clear in poll after poll conducted over a span of multiple decades. Raising state tax rates on top earners is an effective way to begin chipping away at this longstanding and widely acknowledged inequity while simultaneously helping states weather the revenue shortfalls brought on by this crisis.

While the vastness of the fiscal crisis still demands significant federal aid to states and localities, all states should follow New Jersey’s lead and consider equitable revenue-raising solutions in their pandemic responses in the coming months.