Next week, voters in Multnomah County, Oregon could shift longstanding inequities in the tax code by implementing a pathbreaking local 0.75 percent capital gains tax that would fund legal representation for tenants facing eviction. As the Oregon Center for Public Policy has highlighted, capital gains are a primary driver of racial and economic inequality in Oregon. Taxing capital gains in the county with Oregon’s largest city (Portland) is a step towards rectifying the state’s history of entrenched racism. The tax would fund legal support for tenants facing eviction, especially important given that landlords could raise rents by as much as 14.6 percent next year.

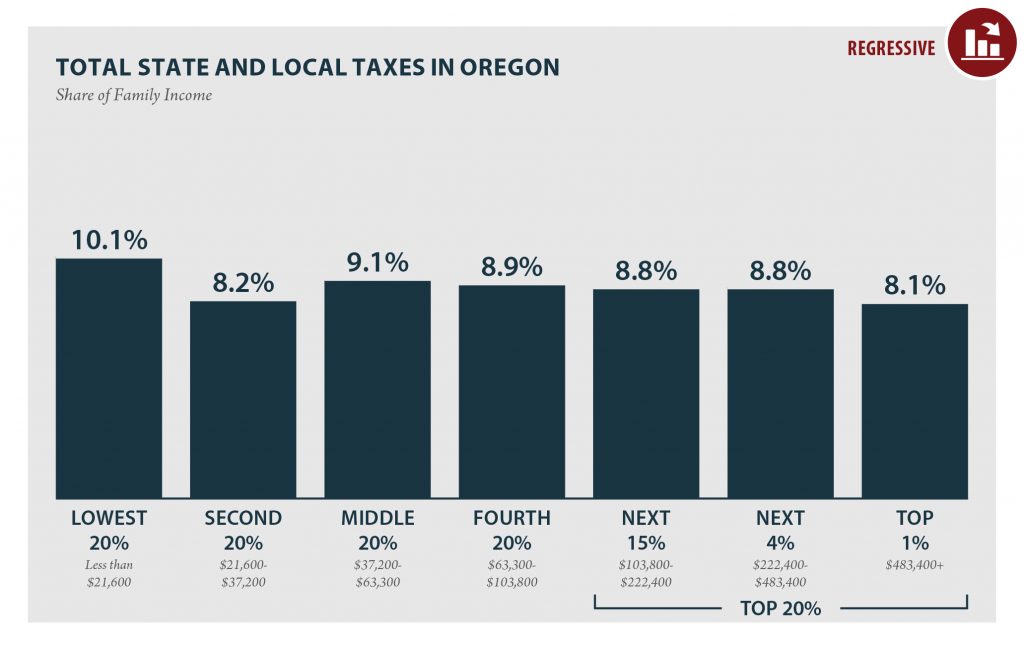

At nearly every turn, Oregon’s tax policies widen inequality; as a result, the top 1 percent pay less state and local taxes as a share of income than the poorest residents. Taxing capital gains at the local level is an important and exciting move in the other direction – to tax income from wealth and use it to address crucial needs.

Capital gains are among the most unequally distributed sources of personal income; the richest 0.1 percent of Oregonians took home over a third of all capital gains income in 2020. Most Oregonians of all races receive little if any capital gains income. Generations of policy advantage and discriminatory policies have led to the vast majority of income from wealth like capital gains flowing to white families. White families comprised 65 percent of respondents in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), yet held 89 percent of unrealized capital gains in excess of $2 million; Black and Hispanic families each held about 1 percent, despite making up 14 percent and 10 percent, respectively, of families in the survey.

There is already a massive carveout for long-term capital gains and dividends at the federal level. Not only are federal tax rates on capital gains lower than income from labor, individuals can enjoy an increase in wealth without having to claim any income due to deferred taxes on unrealized gains. This perk allows some extremely wealthy people to pay zero federal income taxes on most of their true income. Wealthy people can also pass on billions in wealth to their heirs who will not be subject to any income taxes on the change in value of the asset due to something called the “stepped up basis” rule. Therefore, taxing capital gains at higher rates at the state and local level would make the overall tax code more fair.

Local capital gains tax could help communities held back by Oregon’s racist roots

Despite Oregon’s modern-day liberal reputation, it was founded as a white “utopia” and had the highest per-capita Ku Klux Klan membership in the nation in the 1920s. It was the only state with a constitution that explicitly forbade Black people from living, working, and owning property. The repercussions of discriminatory policies – land grants that shifted land ownership from indigenous groups to mostly white settlers, Black-exclusion laws, voting restrictions – can be felt today in disparities in homeownership rates, health outcomes, and graduation rates.

Even after Black people were permitted to live in Oregon, “urban renewal” projects in Portland decimated the few Black communities that existed. Recent studies found that Black and indigenous students faced more drastic discipline in public schools than their white counterparts; among older residents, Black and Latino renters face steeper rents, deposits and fees than white residents. Racial discrimination and exploitation seep into every aspect of daily life. According to a 2014 joint report by Portland State University and the Coalition of Communities of Color, “African-Americans in Multnomah County continue to live with the effects of racialized policies, practices, and decision-making.”

Less frequently discussed is how historic and present-day tax policy contributes to these deep inequities. After the outbreak of the Civil War, the state legislature passed a law requiring every Black, Chinese, Hawaiian, and mixed-race Oregonian to pay a $5 head tax (approximately $150 today); those who could not were required to do forced labor. As Juan Carlos Ordóñez explained in an episode of Policy for the People, Oregon no longer has explicitly racist tax laws but the tax structure still represents the economic interests of well-off white residents whose generational wealth can be tied to historic discrimination.

For example, Oregon spends roughly $500 million a year on a mortgage interest deduction that primarily benefits higher-income residents who itemize deductions rather than take the standard deduction. A 2022 audit by the Oregon Secretary of State’s office found that roughly 18,000 taxpayers with incomes in the top 1 percent received more from the tax break than the 727,000 taxpayers in the bottom 40 percent combined.

Income tax preferences for homeowners disproportionately subsidize white families who have higher homeownership rates even at the same income levels. Preferable tax treatment for homeowners is especially problematic given Oregon’s history of racial segregation and disinvestment in Black neighborhoods. To quote the Portland State University and Coalition of Communities of Color report again: “In Portland, as in other cities, strong and cohesive Black neighborhoods were formed out of segregation but were partially dismantled by highway and redevelopment construction and redlined, or systematically denied credit and investment, leading to decline.”

Not only do policies like the mortgage interest deduction foster racially disparate outcomes, Oregon voters enshrined property tax limitations in the Constitution that benefit the most well-off property owners at the expense of most state residents since those with the highest-valued homes receive the largest property tax discounts. The constitutional amendments – Measures 5 and 50 – detached property taxes from market value, distorting property tax bills and making it impossible for Oregon’s local governments to raise enough revenue to meet residents’ basic service needs. Further, researchers found that the property tax limits accelerate gentrification since the biggest beneficiaries are high-income people moving into gentrifying areas.

In other words, not only did policies at the local, state, and federal level hamper Black residents’ ability to build wealth through homeownership, state tax policies continue to exacerbate the racial wealth and homeownership gap. And it’s not just the mortgage interest deduction. The Oregon surplus “kicker” credit, a rebate triggered when actual state revenues exceed forecasted revenue by at least 2 percent, primarily flows to the richest 1 percent. According to the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis estimates, the richest 1 percent of families receive an average of $42,000 from the kicker in 2024 while the poorest 20 percent receive an average of just $60.

The proposed local capital gains tax is sensible

As is common when policymakers try to reduce wealth and racial inequities through the tax code, the usual suspects have come out of the woodwork with fearmongering about administrative hurdles, volatility, and economic growth. These arguments are easily dismissed. The best way to address potential volatility is by relying on a variety of taxes – which Multnomah County already does – and by having a strong Rainy Day fund.

There is little connection between lower capital gains taxes and economic growth. While there is less evidence about the impact of local capital gains taxes, the research at hand and state-level findings suggest that preferential rates do not drive growth. It’s telling that many of the states ranked as the best for venture capital investment are also those states with among the highest capital gains tax rates – because special tax treatment is not the primary factor when making business decisions. This should not be surprising if you consider the main drivers of investment – strong public infrastructure, good education systems, and proximity to markets. The Eviction Representation for All coalition provides examples of how low the 0.75 percent tax would be, even for most high earners. Multnomah County will remain a vibrant community with strong amenities and public services.

When evaluating Ballot Measure 26-238, we need to put it in historical context as well as the context of our entire federal, state, and local tax structures. Nor can we ignore the beneficiaries of the proposed tax – tenants facing eviction who are disproportionately Black and Hispanic women. Our government structures have systemically held back people at risk of eviction from homeownership, making them more vulnerable to rent increases and homelessness.

Tax policy can be a powerful tool for addressing racial and economic inequity and public needs, or it can worsen them. When poorly designed, state tax policies can further concentrate wealth at the top, amplify racial wealth gaps, and constrain local revenue. State tax breaks and property tax limits amplify racial wealth gaps by providing exorbitant savings to mostly white, wealthy homeowners and accelerating gentrification. The property tax limits also constrain local revenues so local governments have few resources to support tenants facing eviction. Ballot Measure 26-238 is a chance to move in the other direction: to tax the very wealthiest residents and fund a dire need faced by those struggling most in our system.

At every turn, tax policies have made Oregonians of color more susceptible to displacement and eviction. It is therefore fitting that the revenue from the proposed capital gains tax should support the very people who have been exploited from other tax policies. Next week, Multnomah County residents have the opportunity to begin to repair this upside-down system.