With home values rising across the country, some residents are increasingly unhappy with their rising property tax bills.1 As legislators search for solutions, it is important to realize we have been here before — and we know what does not work. The last time states were persuaded to “fix” their property taxes by passing tight restrictions, in the 1970s and 1980s, they enacted a wave of measures that have fallen spectacularly short of their promises. These restrictions have failed to curb housing cost growth and instead led to greater inequality, loss of vital public services, and – ironically – even more public frustration with how we pay for schools and other local services.

Across-the-board property tax cuts create less fair local tax systems in the long run. State legislators and local governments should prioritize the residents who can least afford their property taxes, not the residents and businesses who can.

Key Takeaways

- Property tax limits have done nothing to reduce the cost of housing, and in some cases have made new housing construction more expensive.

- Property tax limits create inequities in the property tax system and generally favor wealthy property owners over low-income property owners by taxing properties differently depending on length of ownership, whether someone rents or owns their home, or if they live in a fast-growing community.

- Property tax limits have led to reduced local services, instability in local finance including local debt, increased reliance on regressive tax options, and more state funding to fill the gaps.

- Property tax limits have failed property owners and fueled frustrations that there is inherent unfairness in the system. This has paradoxically led to proposals to abolish property taxes, particularly in states with extreme property tax limits.

Overview

The so-called “tax revolt” of the 1970s and 1980s was a movement against rising property taxes that eventually morphed into a larger pushback against the concept of taxation.2 This took the form of constitutional and statutory changes to state property tax systems that limited local governments’ ability to pay for their own services. By the end of the 1980s, over a dozen states had severely curtailed localities’ ability to tax property fairly and accurately, instigating a change in how municipalities taxed residents. Tax and expenditure limits existed in states as far back as the 1870s but took on a new tenor and severity during the anti-tax revolt.

Economic historians and public finance experts point to an unfortunate combination of rising home prices and stagflation – the trio of slow economic growth, inflation, and high unemployment as a leading cause of these anti-tax movements. Even though property taxes are a relatively small part of housing costs, they are visible to homeowners, and crucially, a lever for political leaders to pull to satisfy voters.

As purchasing power stagnated, leaving some households asset-rich and income-poor, residents felt increasingly resentful of their property tax bills. Home prices rose so quickly that the share of property tax paid by commercial properties shrank significantly.3

Local governments also faced rising costs to provide crucial public services, leaving them unable to cut rates for struggling property owners.

Polling at the time revealed resentment about how people felt tax dollars were being spent and a fundamental misunderstanding of how local, state, and federal tax dollars were allocated.4 Political headwinds against perceived and real malfeasance led to mistrust of state and local governments. That mistrust calcified into a feeling among many voters at the time that government at all levels was wasting taxpayer money.5 Wealthy anti-tax advocates and conservative elites took advantage of these trends in fast-growing states to push a much more extreme policy agenda than many voters initially wanted.

The nationwide anti-tax movement that followed used four different types of limits to control the growth of property taxes.

- Assessment limits constrained the growth of the assessed values of properties through caps on growth over time, or on the individual property’s value.

- Levy limits restricted the growth of tax levies or tax rates, which controlled the amount that municipalities could raise taxes.

- Revenue limits limited the amount of money municipalities could bring in, and either required governments to refund taxpayers or put a preemptive limit on how much they could request in the first place.

- Expenditure limits constrained how much localities could spend of “own-source funds,” or taxes the cities, schools, and counties generated themselves.

Policymakers had better options available – namely, property classification and property tax circuit breakers – but did not make those options available to constituents either due to poor timing or lack of political will.6 This report provides a history and description of the unintended consequences of poorly targeted tax limitations. It will examine some of the economic effects of California’s Prop 13, Colorado’s Gallagher Amendment and Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR), Massachusetts’ Prop 2 ½, Michigan’s Headlee Amendment and Proposal A, New York City’s assessment limit, and Ohio’s HB 920. (For a more exhaustive list of tax limits, refer to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy’s 172-year history.)

What Do These Tax and Expenditure Limits Do?

| State | Law | Major Elements | Constitutional or Statutory Change? | Year(s) passed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | Proposition 13 | Municipalities can only tax 1 percent of total assessed value. Assessed values on individual properties may only grow by the lesser of 2 percent or inflation. Assessed values rolled back to 1975-76 values. Assessed values are reset at sale. Supermajority required for new taxes or municipal bond offerings. This is unique because all the limitations apply to both commercial and residential properties. | Constitutional | 1978 |

| Colorado | Gallagher Amendment/TABOR | The Gallagher Amendment capped the share of the property tax levy residential properties could take up. It was repealed in 2020. TABOR put a hard cap on levy growth with a requirement for governments to refund any excess revenues. | Constitutional | 1982/1992 |

| Massachusetts | Proposition 2 1/2 | Placed a 2.5 percent growth cap on revenues and levies excluding new construction. Required voter approval to raise taxes. | Statutory | 1980 |

| Michigan | Headlee Amendment/ Proposal A | Headlee limited revenues from assessment increases and required voter approval for any increase in taxes. Prop A put a 5 percent growth cap on individual residential property tax bill growth and adjusted school funding formula. | Constitutional | 1978/1994 |

| New York | Assessment Limit | Capped the growth in assessments in the “special taxing districts” of New York City and Nassau County. Created assessment classes for different types of property and assigned different rate-sharing among those property classes. Two separate levers for adjusting the share each type of property will pay, as well as the level at which those properties are assessed. | Statutory | 1971 |

| Ohio | HB 920 | Partial levy limit with strict requirements for new growth. Any increase in assessment values will cause tax rates to go down without other approval from voters. | Statutory | 1976 |

|

ITEP.org

|

||||

What Were the Effects on Taxing Districts?

By implementing property tax limits, state governments intentionally constrained localities and schools’ ability to raise or spend revenues. This top-down approach from state legislatures treats all taxing districts the same, even when there are substantive differences in population, economic conditions, or structure of local government.

Though the policies were generally portrayed as a tax cut, they were not framed to voters as a hit to municipal financial stability. Some voters might not have understood that these limits would cut local government funding or might not have grasped the degree to which that would happen or how it might affect their cities or schools. The erosion of local government authority over their own tax bases has had massive implications for how local governments and state governments interact.7

For instance, when California’s Prop 13 passed, most voters assumed the state would use its surplus to make schools and counties whole – which was true until the surplus ran out. Estimates at the time anticipated 50 to 75 percent losses due to Prop 13, and the state spent much of its reserves over the next few years trying to fill in the gap for local governments. Counties in particular came to rely overwhelmingly on state funds, as many of the duties counties carry out relate directly to state priorities – health care, the criminal legal system, state highway maintenance, and other regional efforts.

Massachusetts experienced something similar. In the wake of Prop 2 ½, taxing districts across the state increasingly relied on state aid to be made whole. When the state reduced available funds to municipalities, those municipalities turned around and opted for tax limit override elections.8 Part of the reason similar tax limitations being proposed today are so dangerous is that many states do not have the same capacity to make local revenues whole as California and Massachusetts did. What’s more, cities may not have consistent access to state aid and may even have conflicting priorities with the state.

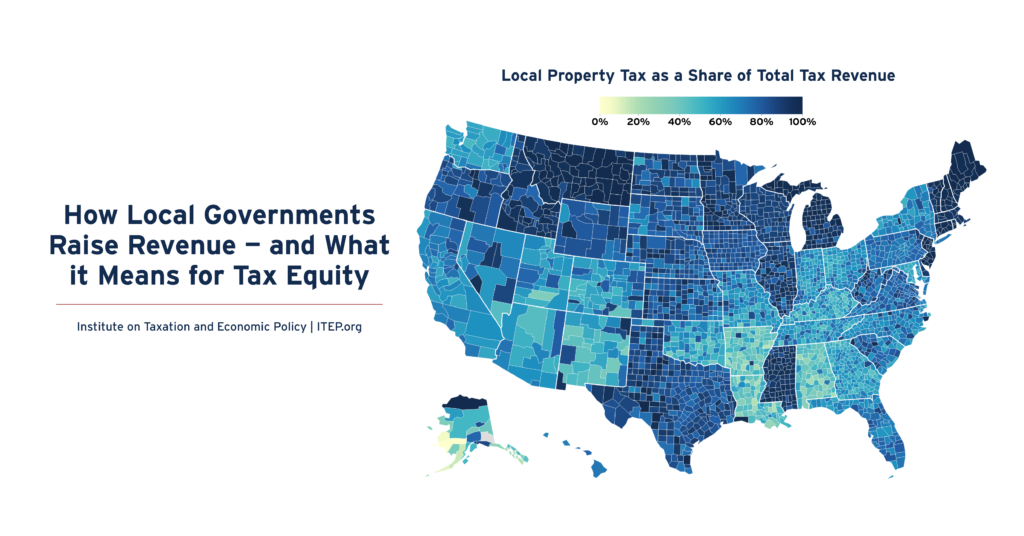

Many cities have therefore responded to property tax limits primarily by expanding the use of regressive taxes, like sales taxes and user fees.9 Colorado cities and counties also have a number of local sales taxes, often earmarked for specific services that would likely otherwise be funded via property taxes. In 2019, sales taxes made up nearly 33 percent of local government revenues in Colorado – almost double the national figure of 18 percent.10 Massachusetts municipalities are barred from having their own sales or income taxes, and municipalities have repeatedly cut services because of a lack of alternative funding.11 Massachusetts has also seen growth in user fees and charges as a result of property tax restrictions.12

In 2019, sales taxes made up nearly 33 percent of local government revenues in Colorado – almost double the national figure of 18 percent.

Revenue limits can lead to ratcheting in which limits are reset to a new standard lower than previous years. The tax revenues are then “ratcheted down” as new growth is limited to the growth of a smaller baseline amount. This can sharply constrain public budgets, particularly during recessions when revenue is lower and during times of inflation when costs get higher. It can result in sharp declines in real dollar revenues so that municipalities collect even less than when properties were worth the same amount decades prior. California and Colorado have both widely adopted special “parcel taxes” which are a flat fee per parcel. They sound like property taxes but are often untethered from the value of a property, meaning low-value and high-value homes may pay the same amount. Though these are defended by municipalities as being an efficient way to pay for services like sidewalks and trash service, it is yet another fee charged to owners that would be more efficiently and equitably paid for through the property tax system.

Direct Democracy

Tax limits are usually paired with a way for voters to override limits if they wish.

These overrides are often voted on during off-year or special elections, may be described unclearly in ballot language, and can be even more subject than other policies to the influence of special interests, wealthy donors, or corporations who have a vested interest in the outcome. The tradeoffs are very tangible for these special interests; for most residents, the benefits of the overrides are real but much more abstract.

Ohio’s HB 920 has created a convoluted property tax system that requires the approval of voters for basic inflation growth. Property tax levies are made up of multiple parts, some permanent and others that require voter approval.13 As a result, Ohioans are constantly asked to vote for fixed sum and fixed rate levies — two different votes for two different levies with different lengths of applicability, rate adjustment, and taxing districts. These levies support ongoing services above the millage minimums set by the state.

Because these are voter approved, they often require annual or biannual elections to continue supporting government services. Ohioans are constantly asked to go to the polls to support government services they already approved. As a result, homeowners in Ohio vote at rates far higher than non-homeowners – in some places, nearly twice as much.14 This means that homeowners, who are nearly always wealthier than renters by virtue of owning a home, are deciding elections for everyone.

TABOR in Colorado has also led to an increased number of ballot initiatives. Localities must go to voters to increase property tax assessment ratios. They also ask voters to override the refund cap to allow the government to keep money rather than refund it to taxpayers. Municipalities can also completely override the TABOR cap. A 2003 study found that a high proportion of Colorado ballot initiatives to override TABOR passed, but often had turnout hovering around 30 percent15 — other studies have shown that turnout in those elections is below 50 percent.16 As in Massachusetts, Colorado has had different results based on the overall growth rate of the community; growing communities can more easily overcome tax limits, while slow-growing or declining communities may not.17

Local Debt

Property tax limits can increase the cost of borrowing and make borrowing more legally complex. Many of these laws specifically limit the amount of debt a taxing district can take on or make it more difficult for those municipalities to pass bond ballot measures.

Ratings agencies tend to give lower credit ratings to municipalities under strict tax and expenditure limits because they perceive an increased risk of municipal default – in other words, if they think a city may have a harder time paying back its debt, they may lower its credit rating. When credit ratings are low, municipalities have to pay a higher interest rate to attract investors. This makes the cost go up, and in return, requires higher tax revenues to pay back investors, further driving up tax rates.

The empirical evidence for this shows a small but consistent effect.

In California, issuing bonds became politically prohibitive for local governments, leading to the proliferation of Certificates of Participation and the creation of Mello-Roos bonds.18 Both tools are much less transparent to the public, both because they are not voted on the way traditional bonds are, and, in the case of Certificates of Participation, are technically held by a government-owned corporation. Because Mello-Roos bonds were generally used by placing liens on properties, some homeowners in new housing developments paid more in Mello-Roos taxes than in property taxes to their city, school districts, and county combined.19

Though it would be more efficient to have larger infrastructure investments from the federal government,20 taxing districts are on their own when replacing roads, improving water infrastructure, and building libraries. These types of tax limitations further erode the ability for local governments to invest in their communities.

School Funding

In many states, these property tax limits also came in conflict with school reform and school funding changes.

Prior to the 1970s, schools were funded almost exclusively through property taxes in many states. This led to vast differences between lower- and higher-income communities. A series of lawsuits in the 1970s and 1980s forced states to equalize school spending between different school districts. This meant that some schools were capped at the per-pupil property tax revenue they could collect, while others received additional funds from the state. A meta-analysis from 2009 found that tax and expenditure limits often led to an increase in state funding, but an overall decrease in education resources.21

Three examples point to how complicated these school funding issues can be.

In Massachusetts, Prop 2 ½ has unintentionally led to differential school spending results based on how high the property values are. In lower-income areas, the state spends more money per pupil to make up for the lack of property tax revenues. In higher-income areas, voters can override the cap and can cover the per-pupil spending themselves. However, middle-income districts are often squeezed. While they frequently have levels of per-pupil spending that are adequate for the state, they receive no extra benefit, nor are residents willing or able to spend more, meaning those school districts are stuck with fewer resources.

Michigan had a different problem. Proposal A forced Michigan to move to a state school funding model. This led to a more equal school funding system, getting closer to equal amounts of spending per student by the early 2000s. However, Michigan school districts also dramatically expanded charter schools around the same time, driving up the costs of the statewide funding model and forcing the state to pay more per-pupil to charter schools than to public schools, in turn forcing public school districts to continue to rely on local property tax revenues.22 There is also evidence that state funding of schools stagnated, and in fact was lower in real dollars in 2015 than it was in 1995.23

Ohio’s complex property tax system means that there are seven different factors that contribute to the rollback mechanism that affects local school property taxes.24 This combination of factors has still managed to create regressivity that requires fixes. A recent state auditor report notes that the state recently adjusted the state aid formula to school districts but remarked that “the level to which the taxpayers of each district are willing to provide support can vary greatly.”25

What Were the Housing Effects?

Property tax cuts give a tax benefit to existing homeowners. They do not lower the price of buying a house for new buyers. Many types of property tax cuts are also of limited benefit to renters, both because it takes time for rental market rates to adjust to a new property tax level and because landlords tend to keep a portion of the tax savings for themselves.

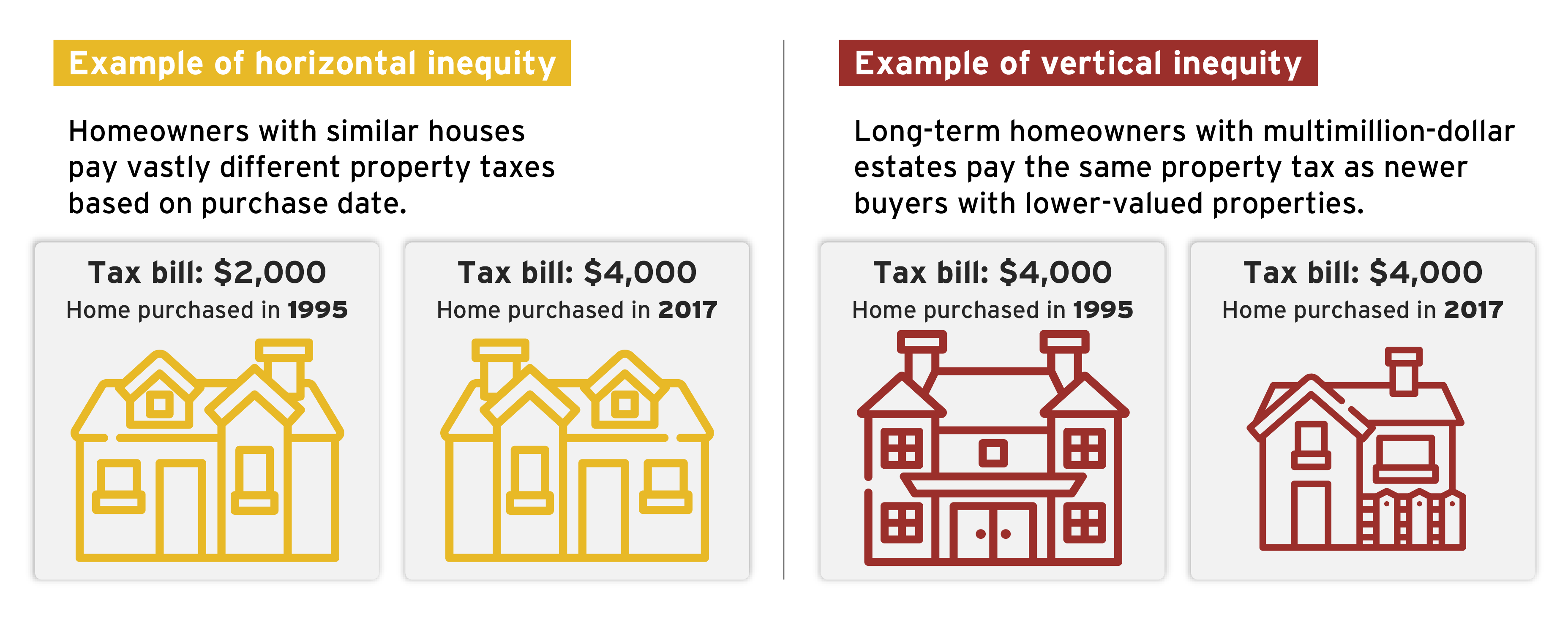

Across nearly all states, some amount of either vertical or horizontal inequity has occurred due to the design of these caps. The housing effects are most pronounced in California, but there have been recurrent housing issues in many of these states.

There are three main reasons Prop 13 has contributed to California’s severe housing crisis, with median home values more than double the national figure.26

First, the tax cut operated as a protective scheme for people who already owned property. Since Prop 13 capped the amount of growth from the point of sale, owners who have owned properties for longer pay a smaller share of the overall property tax levy. This leads to neighboring homes with similar market values having very different property tax bills, entirely based on the length of ownership.27 This has exacerbated the racial homeownership gap in California, with Black and Hispanic Californians having less housing wealth than white households. Ongoing residential segregation has meant that the value of Black and Hispanic homes grows at a slower rate than those in majority white areas. Combined with higher aggregate incomes and longer homeownership tenures for white residents, Black and Hispanic homeowners receive less in tax savings from Prop 13.28

Second, it has encouraged residents to stay in their homes beyond necessity. Economists call this a “lock-in” effect.29 Older homeowners with larger homes may not be able to afford the property taxes on a new residence, so they stay in the family-sized homes they bought decades ago. This means those homes are not available for newer families who may still have children in the house. This drives up the cost of available housing, making long-term homeowners richer by making it much less expensive for them to stay in their oversized homes than to move to a more manageable residence.30

Third, Prop 13 has incentivized California municipalities to prioritize zoning for commercial properties, particularly those that generate sales tax revenue. Prop 13 is unique among assessment limits because it also applies to commercial properties. This means that commercial properties like office buildings, shopping malls, and even Disneyland are perhaps paying tax bills based on 2 percent annual growth since the 1970s.31 As a result, commercial properties hold a smaller share of the overall tax bills in the state than they did in the 1970s.32

Downward pressure on property taxes has led municipalities to increasingly allow the development of properties like malls and car dealerships in order to generate sales tax revenues,33 Because housing developments do not generate substantial new revenue, municipalities and counties have levied fees on development called impact fees to account for the impact new residential development will have on city resources, like sewer and water connectivity. Those too drive up the costs of newly built homes, driving the incentive for properties to be larger, single-family homes farther from the urban core.

Michigan’s assessment cap has created many of the same distortions.

For instance, a study in Michigan found that Proposal A led to a reduction in effective tax rates for long-term owners that reduced tax bills up to 19 percent from 1994 to 2010.34 A different study found that widespread misunderstanding about the length of time the property tax cap applied led homebuyers to overpay an average $10,000 for the temporary tax benefits of the tax cap.35 Homebuyers attempted to “buy” lower property tax bills by purchasing homes in the time period between when homes were annually increased January 1 and when tax bills were due, which could be months later. However, the purchase price often far exceeded the actual tax benefit, leading to gains for home sellers that had nothing to do with the physical property itself.

Researchers have also observed that artificially constraining property values has negative ramifications for multifamily and affordable housing. In New York City, the cap on growth in assessment values gives a benefit to long-term homeowners, who tend to be wealthier and own more valuable properties than newer owners – just like in California.36

Research from the Rent Guidelines Board shows that even with offsetting property tax exemptions, rent-stabilized units face increasing property taxes, only some of which are offset by the state’s multiple property tax exemption schemes. Those schemes exempt certain new or recently renovated buildings from the full tax bill, but leave owners of non-qualifying properties stuck with the full bill.37

In addition, owners of similarly valued properties are paying vastly different tax bills because of the combination of differential tax rates and different assessment ratios for single-family homes versus larger multifamily buildings. The effects of those two policy choices mean that mansions in Manhattan and Brooklyn are taxed six times less than similarly valued multifamily properties in the same neighborhood. This drives up rents for the residents of multifamily units and gives an artificial tax break to owners of mansions. This means majority Black neighborhoods see higher effective tax rates than majority white neighborhoods, since Black New Yorkers are more likely to live in multifamily units.38

In Colorado, the Gallagher Amendment capped the share of residential property tax bills at their 1985 amount. This kept residential properties at 47 percent of the overall property tax share for the entire state. While this sounds like a plausible way to control for growing home values, it meant that communities were constrained to state growth criteria, not local growth criteria. In fast-growing parts of the state like Denver, Boulder, and Aurora, this kept property taxes low for old and new residents. However, in rural areas of the state, it held down property tax revenues so much that rural municipalities were forced to deeply cut services.39

Assessment caps also hurt homeowners when home values fall. A recent book by Bernadette Atuahene tells the story of how the Headlee Amendment and Proposal A hurt Detroit and Detroiters immensely.

During the Great Recession, home values in Detroit fell faster and further than in much of the rest of the country. The city continued to illegally assess properties nearly 70 percent more than they were worth because of the expected loss in revenue. This overassessment pushed thousands of Detroiters out of their homes through property tax sales, leaving people – particularly Black Detroiters – stripped of their housing wealth.40 When Detroit started growing post-Recession, the city was legally barred from taking advantage of rapidly rising home values because of Proposal A – meaning everyone’s tax rates stayed high.

Other types of caps can also hurt housing development. In Massachusetts, many cities have been incentivized not to approve new housing developments because of how new growth is calculated in Prop 2 ½. Colorado treated affordable housing as “discretionary” spending, meaning the state could eliminate line-item funding whenever it could not afford to spend.41

Did Tax Caps Actually Satisfy Property Taxpayers?

Proponents of across-the-board tax cuts like property tax limits often defend them as saying they are helpful to homeowners, who can anticipate costs and not be pushed out of their homes due to rising property taxes. These can have a “progressive” veneer of protecting long-term homeowners, who tend to be seniors with lower incomes than working-aged people.42 The issue is that these policies have not satisfied taxpayers facing confusing, arbitrary tax policies that distort the behavior of governments and residents.

The best example of this is Ohio. HB 920 made the property tax system so exhaustingly complex and unsuccessful at constraining property taxes that anti-tax advocates have placed a referendum on the 2026 ballot to completely eliminate property taxes in the state. This would bankrupt municipalities throughout the state, but abolishing property taxes would have less political salience if homeowners were satisfied with either the amount they paid or the services they received. A recent study of Ohio found a small uptick in home sales when the cost of public services increased, indicating that lower-income homeowners may be feeling the squeeze of property taxes beyond what they can afford.43

Massachusetts municipalities are overwhelmingly reliant on property taxes because they are not allowed to levy sales taxes. In Boston, the decline in commercial real estate has led to rising dependency on residential properties, leaving homeowners to foot the bill despite higher assessment ratios for commercial properties in the city.

TABOR in Colorado passed shortly after the failure of the Gallagher Amendment to constrain growing property taxes on homes. Though the Gallagher Amendment intended to rebalance property taxes to charge businesses more than residents, all it did was rebalance who paid what portion, not the overall growth in tax revenues. TABOR has constrained revenue much more than voters anticipated, and localities throughout the state have increasingly asked voters to create new taxes, keep already-collected revenues they would otherwise be forced to refund, or override the cap entirely.44 After the Gallagher Amendment was repealed in 2020 because homes made up 80 percent of all taxable value, yet merely 47 percent of the tax base, the state has struggled to find a new solution compliant with TABOR.

Prop 13 was so successful at constraining property tax growth for existing property owners that it has been referred to as the “third rail” of California politics. Every attempt to expand Prop 13 has passed, and most attempts to limit Prop 13 have failed. One of the most controversial parts of Prop 13 is the inclusion of commercial and industrial property. Large commercial property owners, including major businesses, argued against Prop 13 before it passed in 1978, saying this would give a major tax cut to businesses with little benefit to homeowners.45

In 2020, a failed initiative called Proposition 15 would have removed the tax advantage from commercial and industrial property and created a split roll tax system.46 The system would have split the property tax system in two and created different assessment rules for residential and non-residential properties. Anti-tax advocates successfully convinced homeowners that if they ended Prop 13 for businesses, they would do it for homes.

What Should States Do Instead?

The issue with many of these harmful property tax limits is that because so many of them are constitutional amendments, state legislators are incentivized to tweak rather than fully repeal them. Even among the policies that are not written into state constitutions, like New York City’s assessment limit, the political capital needed to do full-scale property tax reform is often lacking, with legislators instead thinking about short-term cuts or minor corrections rather than long-term solutions, including repeal.47 However, there is promise – a new movement in Colorado is gaining steam to repeal TABOR for good.48 We recommend several options to states that wish to manage property tax growth for those least able to pay. These include:

- Passing property tax circuit breakers for homeowners and renters

- Allowing local income taxes to partially offset property taxes

- Equalizing school funding formulas

- Improving assessment practices

The most progressive option for states to contain property taxes in a targeted, equitable way is a circuit breaker.

Circuit breakers offer a tax credit to income-qualified homeowners, appropriately matching the ability to pay for property taxes with the needs of our communities. Circuit breakers protect owners of property that is rapidly accruing value, including in gentrifying or quickly growing communities, as well as people on fixed incomes like seniors and people with disabilities. They also ensure that cities, schools, parks, fire departments, counties, and other special districts can pay for all the essential services we share. Michigan — like 28 other states and the District of Columbia — already has a circuit breaker,49 which has been a lifeline for low-income families and has repeatedly stopped anti-tax advocates from further cutting property taxes in the state.

This is the best political and economic solution to the pressures on homeowners and is also responsive to the needs of the taxing districts reliant on local property tax revenues.

States could also loosen restrictions on other less regressive taxes. Part of the issue with property tax caps is that most municipalities are constrained by other parts of state tax systems that limit their ability to use anything other than sales tax. States could allow local income taxes, progressive real estate transfer fees, high-earner taxes, or vacancy taxes. Ohio, New York City, and some cities in Michigan all have local income taxes that help stabilize local revenues and promote progressivity in local tax regimes.

States should also look to equalize school funding mechanisms. Schools make up a significant chunk of property tax bills nationwide.50 Equalizing school funding statewide would doubly benefit homeowners who wish to pay lower taxes, as well as ensuring that lower-income students are not being harmed by regressive property tax caps that lower property tax receipts and increase funding disparities between school districts.

States can also improve assessment practices and increase the frequency of reassessment. Not assessing properties on a schedule has, as evidenced by California, Michigan, and New York City, led similar properties to have very different tax bills. Accurate, timely assessments will improve correlation between real values and property bills, and will lead to smaller gaps between similar owners.

Since federal funding is likely to be cut further, it is incumbent on state leaders to seriously reconsider the way we fund our local governments. Broadly cutting property taxes only enriches property owners who can afford to pay, with few benefits for low-income homeowners and renters.

Endnotes

- 1. David Schleicher. “Schools and City Governments Rely on Property Taxes. What Happens When Homeowners Revolt?” Slate, Jan 6, 2025. https://slate.com/business/2025/01/property-tax-reform-homeowners-revolt-local-government-budget-resource-inequality.html; Andrew Keshner, “A ‘property tax revolt’ is underway across the country. These numbers explain what’s driving it.” MarketWatch, Apr. 28, 2025. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/a-property-tax-revolt-is-under-way-across-the-country-these-numbers-explain-whats-driving-it-24c944c3

- 2. Robert Kuttner, Revolt of the Haves, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980; Isaac William Martin, The Permanent Tax Revolt: How the Property Tax Transformed American Politics, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008; Michael J. Graetz, The Power to Destroy: How the Antitax Movement Hijacked America, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

- 3. Kuttner 1980 p.7-8; Evelyn Danforth. “Proposition 13, Revisited.” Stanford Law Review, vol. 73, rev. 511, 2021. https://review.law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2021/02/Danforth-73-Stan.-L.-Rev.-511.pdf

- 4. Kuttner 1980; Alvin D. Sokolow. “The Changing Property Tax and State-Local Relations.” Publius 28, no. 1 (1998), pp. 165–87.

- 5. Martin 2008.

- 6. Sherry Tvedt. “Enough is Enough: The Origins of Proposition 2 1/2.” Thesis submitted for Master of City Planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1981. https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/78752/08096611-MIT.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- 7. Sokolow 1998; Jeffrey I. Chapman. “The Continuing Redistribution of Fiscal Stress: The Long Run Consequences of Proposition 13.” Lincoln Institute Working Paper, 1998. https://www.lincolninst.edu/app/uploads/legacy-files/pubfiles/chapman_wp98jc1.pdf

- 8. Dennis Hale. “Proposition 2 ½ A Decade Later: The Ambiguous Legacy of Tax Reform in Massachusetts.” State and Local Government Review, vol. 25, no. 2 (Spring 1993), p. 127.

- 9. Michael A. Shires. “Patterns in California Government Revenues Since Proposition 13.” Public Policy Institute of California, 1999. https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/content/pubs/report/R_399MSR.pdf; Christopher Hoene. “Fiscal Structure and the Post-Proposition 13 Fiscal Regime in California’s Cities.” Public Budgeting and Finance vol. 24 iss. 4 (2004), pp. 51-72. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.0275-1100.2004.00347

- 10. “Colorado State Tax Basics.” Colorado Fiscal Institute, Feb. 2022, p.28. https://www.coloradofiscal.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/CFI-Tax-basics-2022.pdf; Rita Jefferson and Galen Hendricks. “How Local Governments Raise Revenue – and What it Means for Tax Equity.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Dec. 5, 2024. https://itep.org/how-local-governments-raise-revenue-2024/

- 11. Phil Oliff and Iris J. Lav. “Hidden Consequences: Lessons from Massachusetts for States Considering a Property Tax Cap.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 25, 2010. https://www.cbpp.org/research/hidden-consequences-lessons-from-massachusetts-for-states-considering-a-property-tax-cap

- 12. Pengju Zhang and Yilin Hou. ”The Impact of Tax and Expenditure Limitations on User Fees and Charges in Local Government Finance: Evidence from New England.” Publius, vol. 50 no. 1 (2020), pp. 81-108.

- 13. Ohio Education Policy Institute. “House Bill 920: Ohio’s Unique Method for Controlling Tax Increases.” Dec. 2023. http://www.oepiohio.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/OEPI-HB-920-Explanation-Revised.FINAL-SG.pdf; Zach Shiller. “For most, the big increases in local property values won’t translate to a bunch more taxes.” Policy Matters Ohio, Sep. 24, 2024. https://policymattersohio.org/news/2024/09/30/for-most-the-big-increases-in-local-property-values-wont-translate-to-a-bunch-more-taxes/

- 14. Andrew B. Hall and Jesse Yoder. “Does Homeownership Influence Political Behavior? Evidence from Administrative Data.” The Journal of Politics, vol. 84 no. 1 (Jan. 2022). https://doi.org/10.1086/714932

- 15. Judith I. Stallmann. “Impacts of Tax and Expenditure Limits on Local Governments: Lessons from Colorado and Missouri.” Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, vol. 37 no. 1 (2007), pp. 62-65.

- 16. Colorado Fiscal Institute. “TABOR Primer,” 2025, p. 11. https://coloradofiscal.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/2025-CFI-TABOR-Primer.pdf

- 17. Tommy M. Brown. Constitutional Tax and Expenditure Limitation in Colorado: The Impact on Municipal Governments. PhD. diss., University of Colorado at Denver, 1999, p 168. https://digital.auraria.edu/files/pdf?fileid=f9dc48a9-42ac-422f-92a8-6bf6b38b7b15

- 18. Jeffrey L. Chapman. “Proposition 13: Some Unintended Consequences.” Paper presented at the Envisioning California Conference, n.d. (approximately 1999). Accessed from the Public Policy Institute of California. https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/content/pubs/op/OP_998JCOP.pdf

- 19. Prop 13 also constrained the state government’s ability to sell bonds, with a 1999 book estimating it cost the state $2 million for every $1 billion borrowed – a 2 percent increase in overall costs of issuance. James M. Poterba and Kim S. Rueben. Fiscal Rules and State Borrowing Costs: Evidence from California and Other States, Public Policy Institute of California, 1999. https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/content/pubs/report/R_1299JPR.pdf

- 20. There is quite a bit of debate about how to deal with major investments from the federal government. For a longer discussion of the history of federal subsidy of local infrastructure, see: Justin Marlowe and Martin J. Luby. ”Municipal Bond Tax Exemption: History, Justifications, Criticisms, and Consideration of Reforms.” Policy brief from the University of Chicago Center for Municipal Finance and the University of Texas at Austin Center on Municipal Capital Markets, April 2025. https://munifinance.uchicago.edu/exemption/ and Thomas Brosy. “If Congress Makes Muni Bonds Taxable, What Could Happen to States and Cities?” TaxVox, Tax Policy Center, Mar. 13, 2025. https://taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/if-congress-makes-muni-bonds-taxable-what-could-happen-states-and-cities

- 21. Sonali Ballal and Ross Rubenstein. “The Effect of Tax and Expenditure Limitations on Public Education Resources: A Meta-Regression Analysis.” Public Finance Review vol. 37 no. 6 (2009), 665-685. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142109345265

- 22. Oded Izraeli and Kevin Murphy. “An Analysis of Michigan Charter Schools: Enrollment, Revenues, and Expenditures.” Journal of Education Finance, vol. 31, no. 3 (Winter 2012), pp 234-266.

- 23. David Arsen, Tanner Delpier, and Jesse Nagel. ”Michigan School Finance at the Crossroads: A Quarter Century of State Control.” Michigan State University Education Policy Report, Jan. 2019. https://education.msu.edu/ed-policy-phd/pdf/Michigan-School-Finance-at-the-Crossroads-A-Quarter-Center-of-State-Control.pdf

- 24. Howard R. Fleeter. ”An Analysis of the Impact of Property Tax Limitation in Ohio on Local Revenue for Public Schools.” Journal of Education Finance, vol. 21 no. 3 (Winter 1996), pp. 343-365.

- 25. Ohio Auditor of State. “Longitudinal School Finance Study: A Special Report,” Nov. 2024, p. 10.https://ohioauditor.gov/performance/LSFS_2024/Longitudinal_School_Finance_Study_Special_Report.pdf

- 26. Patrick Atwater, Sarah Karlinsky, Jennifer Lovett, and Fred Silva. “Does State Tax Policy Discourage Housing Production?” California Forward and SPUR, Sep. 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26064; Hans Johnson and Eric McGhee. “Three Decades of Housing Challenges in the Golden State.” Public Policy Institute of California blog post, Dec. 3, 2024. https://www.ppic.org/blog/three-decades-of-housing-challenges-in-the-golden-state/

- 27. Danforth 2021.

- 28. Carrie Hahnel, Arun Ramanathan, Jacopo Bassetto, and Andrea Cerrato. “Unjust Legacy: How Proposition 13 Has Contributed to Intergenerational, Economic, and Racial Inequities in Schools and Communities.” Opportunity Institute and Pivot Learning, June 2022. Accessed from the Internet Archive dated Jun. 22, 2022. https://web.archive.org/web/20220622110438/

- 29. Nada Wasi and Michelle J. White. “Property Tax Limitations and Mobility: The Lock-in Effect of California’s Proposition 13.” NBER Working Paper 11108, Feb. 2005. https://www.nber.org/papers/w11108; Joshua Coven, Sebastian Golder, Arpit Gupta, and Abdoulaye Ndiaye. “Property Taxes and Housing Allocation Under Financial Constraints.” SSRN No.4880480. Last revised Oct 23., 2024. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4880480

- 30. Jon Gorey. “A Fair Assessment: Assessment Limits Create Tax Disparities That Obstruct Homeownership.” Government Finance Review, Dec. 2024, pp. 54-59. https://www.gfoa.org/materials/gfr1224-fair-assessment

- 31. Jeffrey L. Chapman. “Proposition 13: Some Unintended Consequences.” Paper presented at the Envisioning California Conference, n.d. (approximately 1999). Accessed from the Public Policy Institute of California. https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/content/pubs/op/OP_998JCOP.pdf

- 32. Lenny Goldberg and David Kersten. “System Failure: California’s Loophole-Ridden Commercial Property Tax.” California Tax Reform Association in collaboration with the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment, May 2010. https://www.mikemcmahon.info/Prop13TaxAnalysis2010.pdf

- 33. Laura Schmahmann. “City Competition for E-Commerce Sales Tax Revenue: Qualitative Evidence on the Politics of Land Fiscalization in California.” Economic Development Quarterly (2025), pp 1-15. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/08912424251331896

- 34. Mark Skidmore, Charles L. Ballard, and Timothy R. Hodge. “Property Value Assessment Growth Limits and Redistribution of Property Tax Payments: Evidence from Michigan.” National Tax Journal, vol. 63, iss. 3 (2010), pp 509-538.

- 35. Sebastien Bradley. “Inattention to Deferred Increases in Tax Bases: How Michigan Homebuyers are Paying for Assessment Limits.” Review of Economics and Statistics vol. 99 (1), Mar. 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00597

- 36. Andrew T. Hayashi. “Property Taxes and Their Limits: Evidence from New York City.” Accessed from SSRN, updated Feb. 2014. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2377590; Tax Equity Now. ”New York City’s property tax system is regressive and unfair. Here are the facts.” Accessed May 15, 2025. https://taxequitynow.nyc/research/

- 37. New York City Rent Guidelines Board. ”NYC Rents, Markets & Trends 2023,” accessed May 15, 2025. https://rentguidelinesboard.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/2023-Housing-NYC-Book.pdf; New York City Housing Preservation & Development, ”Tax Credits and Incentives,” accessed May 15, 2025. https://www.nyc.gov/site/hpd/services-and-information/tax-credits-and-incentives.page

- 38. Matthew Murphy and Ryan Brenner. “Racial Inequities in New York City’s Property Tax System.” NYU Furman Center Blog The Stoop, Jan. 8, 2024. https://furmancenter.org/thestoop/entry/racial-inequities-in-new-york-citys-property-tax-system; Iziah Thompson and Stephen Hoskins. “Footing the Bill: Fifty Years of NYC Overtaxing Tenants, Towers, and Low-Income Communities of Color.” Report co-published by Community Service Society and the Progress and Poverty Institute. March 2025. https://www.cssny.org/publications/entry/footing-the-bill-fifty-years-of-nyc-property-tax-tenants-towers-low-income-communities-color

- 39. Michael R. Johnson, Scott H. Beck, and H. Lawrence Hoyt. “State Constitutional Tax Limitations: The Colorado and California Experiences.” The Urban Lawyer vol. 35 no. 4 (Fall 2003), pp. 817-845.

- 40. Bernadette Atuahene. Plundered: How Racist Policies Undermine Black Homeownership in America. New York: Little, Brown and Co., 2025.

- 41. Michael R. Johnson, Scott H. Beck, and H. Lawrence Hoyt. “State Constitutional Tax Limitations: The Colorado and California Experiences.” The Urban Lawyer vol. 35 no. 4 (Fall 2003), pp. 817-845.

- 42. Isaac William Martin and Kevin Beck. “Property Tax Limitation and Racial Inequality in Effective Tax Rates.” Critical Sociology vol. 42 no. 2 (2024), pp. 221-236. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0896920515607073

- 43. Rebecca Fraenkel. ”Property Tax-Induced Mobility and Redistribution: Evidence from Mass Reappraisals.” Public Budgeting and Finance, vol. 44 no. 4 (Winter 2024), pp. 28-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbaf.12369

- 44. Judith I. Stallmann. “Impacts of Tax and Expenditure Limits on Local Governments: Lessons from Colorado and Missouri.” Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, vol. 37 no. 1 (2007), pp. 62-65; Tom Rown. “Constitutional Tax and Expenditure Limitation in Colorado: The Impact on Municipal Governments.” Public Budgeting and Finance, vol. 20, no. 3 (2002), pp. 29-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/0275-1100.00019

- 45. Jim Shultz. “How Prop. 13 gave California’s richest corporations a multibillion-dollar tax break they didn’t want.” CalMatters, Aug. 17, 2020. https://calmatters.org/commentary/2020/08/how-prop-13-gave-californias-richest-corporations-a-multibillion-dollar-tax-break-they-didnt-want/

- 46. Derek Sagehorn. “Proposition 13 is broken. Annually reassessing commercial properties will fix it.” SCOCAblog, California Constitution Center and UC Law Journal, Sep. 4, 2019. https://scocablog.com/proposition-13-is-broken-annually-reassessing-commercial-properties-will-fix-it/

- 47. Stallmann 2007, p. 65.

- 48. ”Colorado Lawmakers Considering Suit to Overturn TABOR.” Off The Charts Blog, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Apr. 16, 2025. https://www.cbpp.org/blog/colorado-lawmakers-considering-suit-to-overturn-tabor; ”TABOR Reform Stalls Again, Yet Support for Change Keeps Building,” Colorado Fiscal Institute, May 8, 2025. https://coloradofiscal.org/tabor-reform-stalls-again-yet-support-for-change-keeps-building/

- 49. Carl Davis and Brakeyshia Samms. “Preventing an Overload: How Property Tax Circuit Breakers Promote Housing Affordability.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, May 11, 2023. https://itep.org/property-tax-affordability-circuit-breaker-credits/

- 50. Daphne Kenyon, Bethany Paquin, and Semida Munteneau. ”Public Schools and the Property Tax: A Comparison of Education Funding Models in Three U.S. States.” Land Lines Magazine, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, April 2022. https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/2022-04-public-schools-property-tax-comparison-education-models