Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILT or PILOT) programs allow local governments to collect revenue from nonprofits that otherwise would not be contributing to the cost of providing local services.

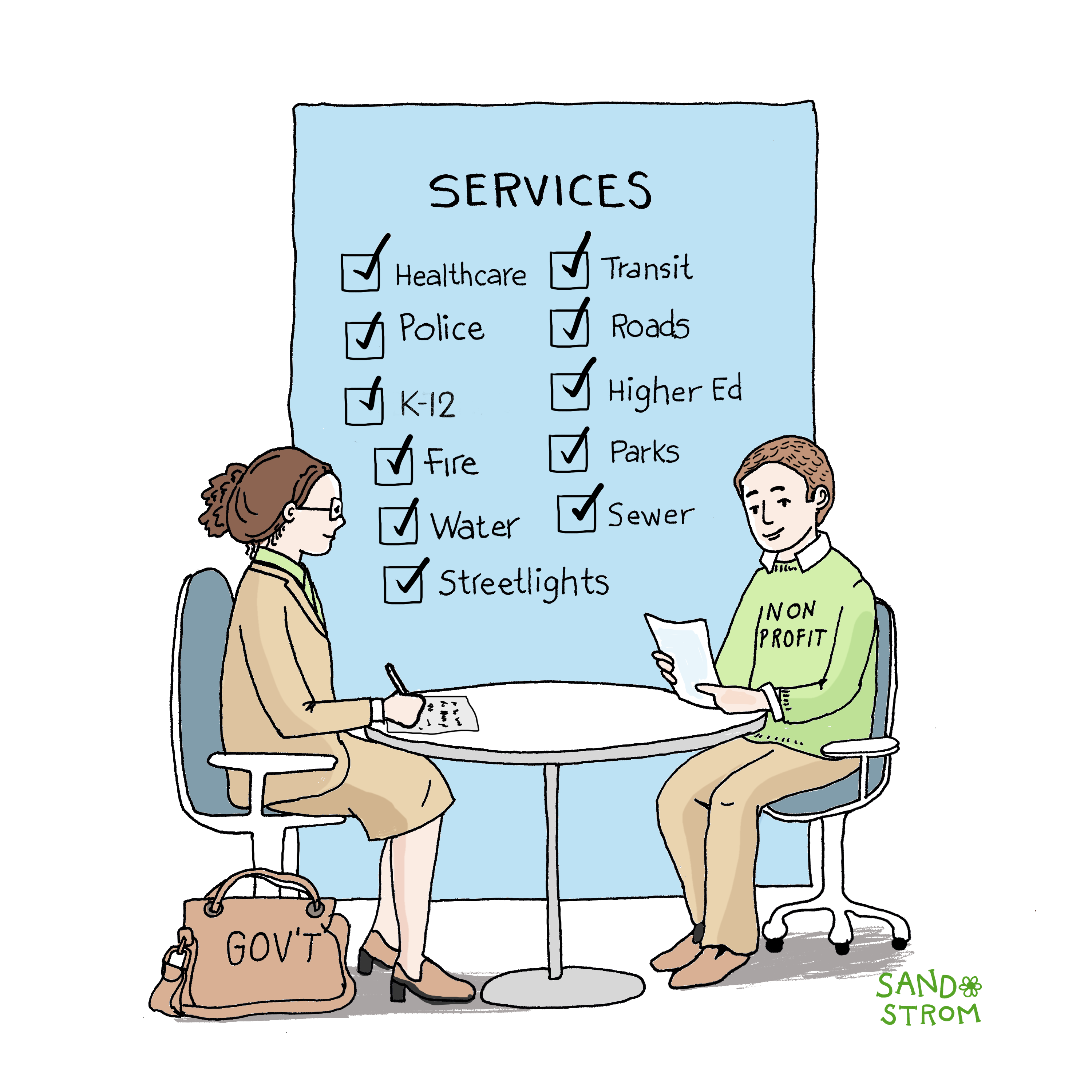

Every state has chosen to exempt most non-profit entities from local property taxes. A building owned by a charitable organization may be exempt from tax even if an identical building next door is fully taxed. These exemptions can make it more affordable for these organizations to pursue their missions. But they can also hamper the ability of localities to collect enough revenue to pay for services like transportation and public safety.

This problem arises most often in areas with many non-profit hospitals, universities, other big nonprofits, or a lot of government-owned land and buildings. For instance, a 2018 study of Boston found that tax-exempt land made up over half of all land area and 34 percent of all property value in city limits.

The PILOT idea originated with the U.S. Department of the Interior in the 1970s as a way for the federal government to reimburse local governments for the costs of services provided to federally owned and managed land. The idea spread to communities with substantial amounts of property owned by non-profit hospitals and universities as a way to make up for the loss in revenue due to state tax exemptions. (The term PILOT can also apply when private companies pay only a portion of what they would normally owe in property taxes as part of a tax abatement deal, and the net result is a deep-discount tax break.)

In some instances, a nonprofit PILOT is negotiated to compensate the locality partially or fully for the revenue loss associated with an organization’s tax-exempt status. Because PILOTs paid by non-profits are usually voluntary, organizations do not always have a strong incentive to sit down with local officials to negotiate such agreements. But communities can leverage the services they provide, like police and fire protection, to negotiate with organizations who may need help in some matter like zoning or permitting. States can encourage such negotiations by establishing an expectation that nonprofits will contribute to their communities financially in exchange for preferential tax treatment.

Some states and localities have more robust systems than others. Connecticut reimburses all municipalities for lost property tax revenue for properties held by the state and some non-profit organizations. Boston, Massachusetts has a PILOT program negotiated with the major universities, hospitals, and museums in the city, though the payments are voluntary.

To improve PILOT programs, the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy suggests using accurate, fair assessed values of exempt land, using a trigger for the dollar amount of property owned past a certain value or threshold, and using community benefit offsets that are robust, trackable, and directly benefit the community.

Related Entries

How Do Real Property Taxes Work?

Property taxes on land and buildings are the oldest and still the largest major revenue source for state and local governments. They fund schools, health care, public safety and other services. They are collected mostly by cities, counties, school districts, and other types of local government, but states typically set the rules for assessing the value of property and imposing the tax, with major implications for tax fairness and adequacy.

What Are the Taxing Authorities of Local Governments?

Tens of thousands of local governments in the United States — from big cities like Los Angeles and New York to rural counties, school districts, and small towns – operate schools, roads, parks, public safety, and other services. To pay for it all, they collect roughly $1 trillion in taxes annually. But states, not just localities, set many of the rules for local taxes, and sometimes misuse that authority to undermine local democracy.

Learn More

- Boston Municipal Research Bureau (2018). “Boston’s Tax-Exempt Property Snapshot.“

- City of Boston (2024). “Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) Program.”

- Kenyon, Daphne A. and Adam H. Langley (2010). “Payments in Lieu of Taxes: Balancing Municipal and Nonprofit Interests.”

- State of Connecticut Office of Policy and Management (accessed March 5, 2025). “Tiered Payment in Lieu of Taxes.”

- U.S. Department of the Interior (accessed March 4, 2025). “Payment in Lieu of Taxes.”