Property taxes on land and buildings are the oldest and still the largest major revenue source for state and local governments.

They fund schools, health care, public safety, and other services. They are collected mostly by cities, counties, school districts, and other types of local government, but states typically make the rules for assessing the value of property and imposing the tax, with major implications for tax fairness and adequacy.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, property taxes provided more than eighty percent of the tax revenue for state and local governments. While this share has diminished over time as states have introduced sales and income taxes, the property tax remains the largest source of local government revenue and an essential mechanism for funding education and other local services.

Property Tax Revenues

Property taxes are an important revenue source. Property values grow at relatively constant rates, even during economic downturns when other tax revenues may fall, so property tax revenues are stable compared to sales tax or income tax revenues. The stability of the property tax makes it among the best options available for providing local governments with a predictable revenue stream that can be used to fund indispensable services like schools, roads, and public safety. Unfortunately, some states have undermined the property tax as a revenue source by enacting tax and expenditure limitations that curtail localities’ ability to collect the tax.

How Real Property Taxes Work

Property taxes on land and buildings are called real property taxes. Even though most states impose property taxes on some items other than real estate, such as business equipment or motor vehicles, real property constitutes most of the tax base.

In its simplest form, the real property tax is calculated by multiplying the value of land and buildings by the tax rate, commonly referred to as a millage rate. A mill is one-tenth of one percent, so an owner of a property valued at $100,000 subject to a 25 mill (that is, 2.5 percent) tax rate would pay $2,500 in property tax.

The first step in the property tax process is determining a property’s value. In most cases, this means estimating the property’s market value, the amount the property would likely sell for. Ideally, these estimates are based on sophisticated, regularly updated calculations of market value. But some jurisdictions fail to conduct regular reassessments, which means that values can get out of date. And without appropriate controls and resources, local assessments can be corrupted by politics or simply fail to reflect the realities of the marketplace.

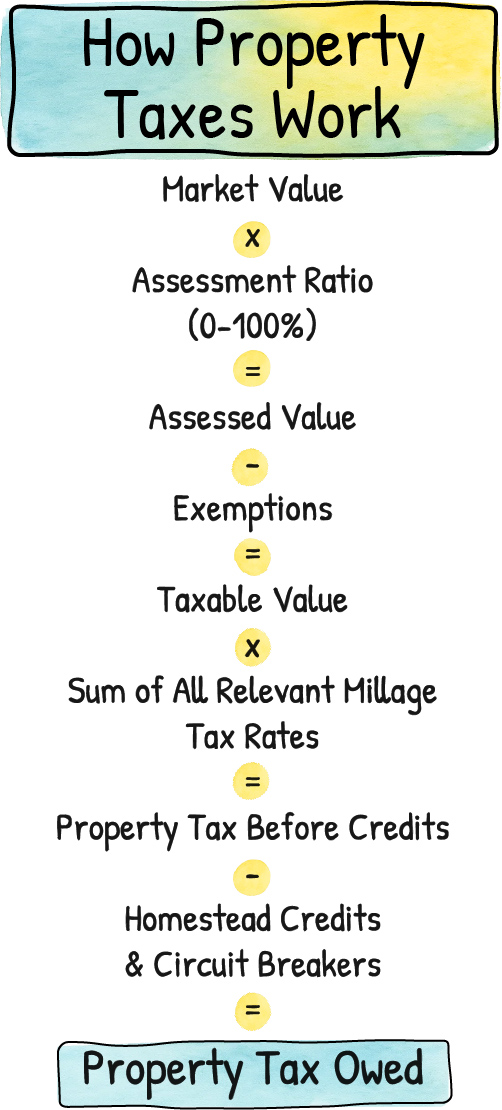

The second step is determining the property’s assessed value. This is done by multiplying the property’s market value by an assessment ratio, which is a percentage ranging from zero to one hundred. Many states base their taxes upon actual market value — in other words, these states use a 100 percent assessment ratio. Other states assess property at only a fraction of its actual value. New Mexico assesses homes at 33.3 percent of their market value, and Arkansas uses a 20 percent assessment ratio.

Assessment ratios can vary by type or “class” of property – for example, residential properties may be assessed at lower rates than commercial properties. Some states place a cap on how much a home’s assessed value can rise from year to year, often leading to vastly different assessment ratios among similarly valued homes. Many states reduce a property’s assessed value further by allowing homestead exemptions for homeowners or other types of exemptions.

The assessed value, minus exemptions, is then multiplied by the millage rate. The millage rate is usually the sum of several tax rates applied by several different jurisdictions, including counties, municipalities, school districts, and other special districts. This calculation yields the total property tax. Some places then allow taxpayers to further adjust what they pay via credits, such as a property tax circuit breaker – a mechanism for helping low-income households meet their property tax obligation.

For a homeowner with a mortgage, the property tax is usually paid by the lender and then incorporated into the homeowner’s monthly payment. Some places allow certain homeowners, usually seniors, to defer their property tax payments until the property is eventually sold.

Who Pays Property Taxes

Almost every household and business in the United States pays property tax to local governments and school districts, either directly or indirectly through rent. Property taxes make sense under the benefits principle, because residents and businesses pay these taxes to support local services like schools and fire protection, and property owners indirectly benefit in the form of increased property values.

The property tax can also be described in part as a tax on wealth, as real property is a major investment for homeowners and businesses alike. But it is unevenly progressive, especially for residences. Because many middle-income people’s largest major asset is their home, they are being taxed on their sole source of wealth. Other forms of financial wealth held by wealthy people, like stocks and bonds, are not subject to property taxes. So even though it is a tax on certain forms of wealth, the property tax is less well connected to the ability-to-pay principle than other wealth taxes like estate taxes.

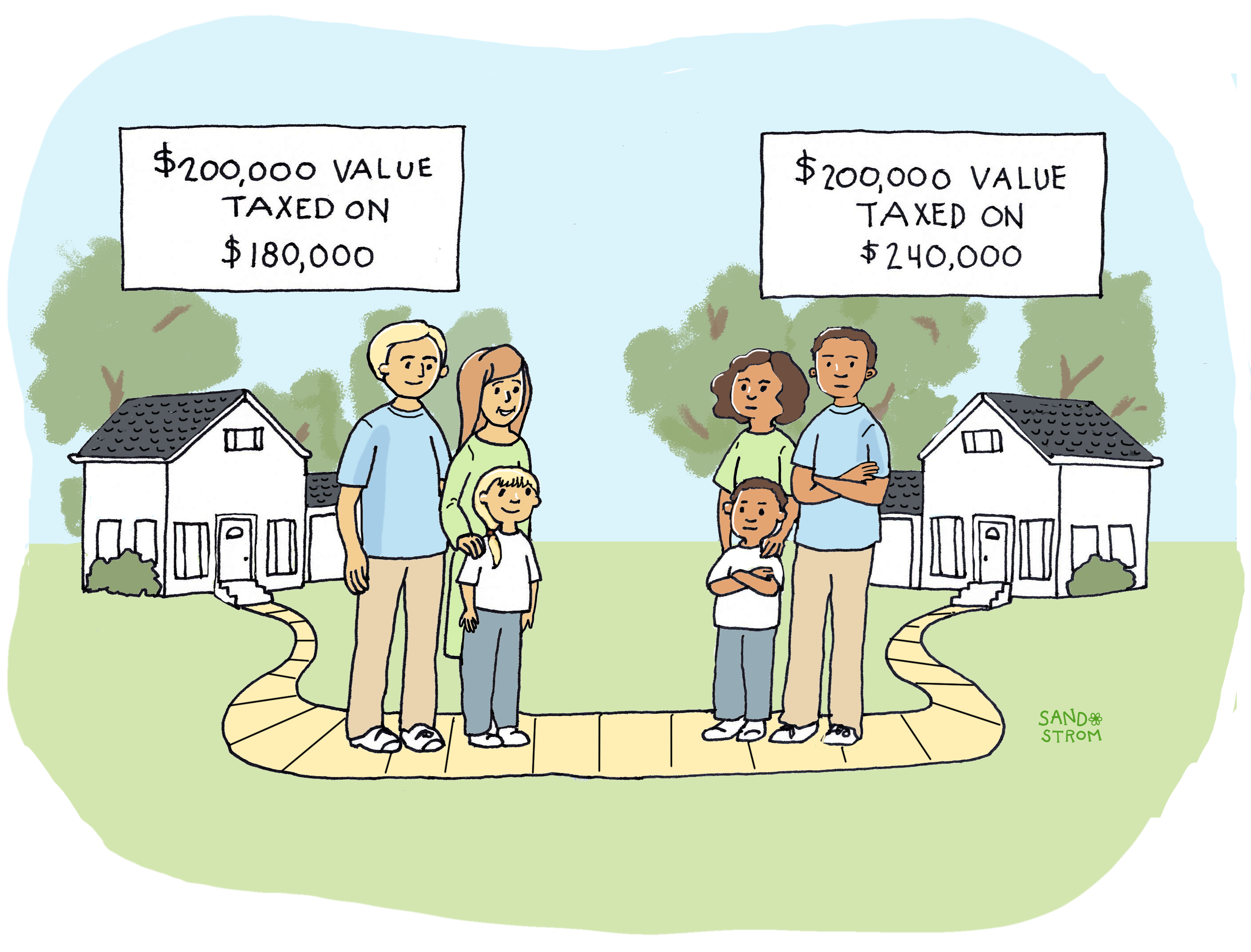

Other flaws make property taxes less equitable than they should be. Large mansions are, by design, often unique and hard to assess accurately, and wealthy families have the resources and political clout to ensure the lowest possible assessment; hence in many places their properties tend to be under-assessed relative to true value. At the same time, studies show that Black-owned homes in many places are systematically over-assessed relative to market value, so Black households owe more taxes than they should.

The property tax system also sometimes strips poorer families of their homes if they can’t pay the tax; in some states, households even lose their accumulated equity in the property. Most people who lose their homes in tax sales are low-income people, especially seniors, unable to keep up with property taxes.

And even when assessments are accurate, a city, town, or school district with relatively low property values likely will find itself forced to tax at higher rates as it seeks to provide the same level of services as its wealthier neighbors. Sometimes state governments provide aid to offset these wealth disparities, but the aid is often insufficient.

Nonetheless, the importance of property taxes as a revenue source suggests that states and localities should work to maintain it and improve its fairness by improving assessments, establishing property tax breaks to homeowners and renters, making collections processes fairer for those who have trouble paying the bill, and avoiding caps and limitations that distort the tax further.

Related Entries

How Do State Tax and Expenditure Limits Work?

A Tax and Expenditure Limit (TEL) is a formula written into state law or into a state constitution that caps revenue and spending of a state and locality. These measures can undermine governmental accountability, degrade essential public services, and create inequitable tax burdens.

What Are the Taxing Authorities of Local Governments?

Local governments in the United States, from big cities like Los Angeles and New York to rural counties, school districts, and small towns, operate schools, roads, parks, public safety, and other services. To pay for it all, they collect roughly $1 trillion in taxes annually. But states, not just localities, set many of the rules for local taxes, and sometimes misuse that authority to undermine local democracy.

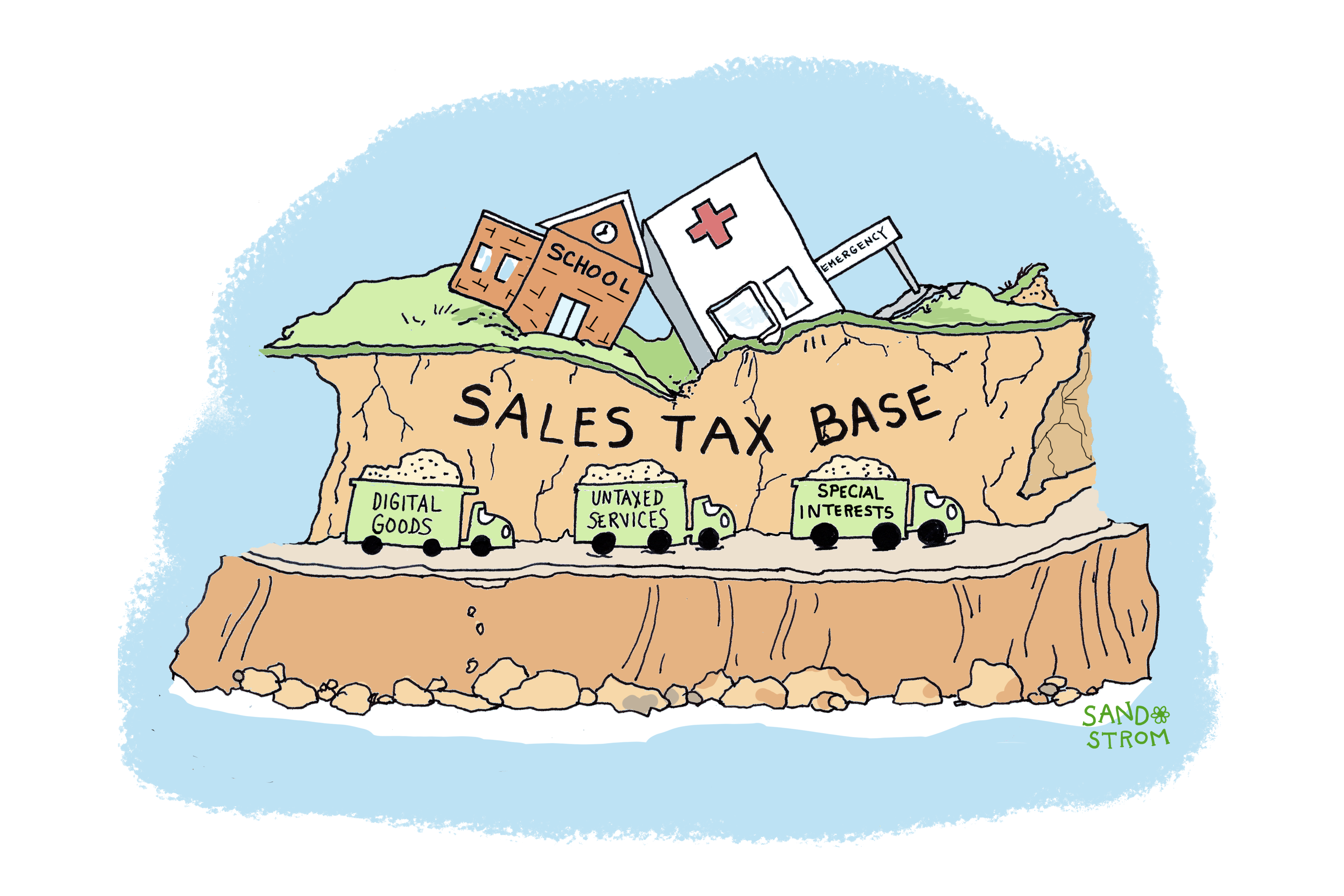

What’s Exempt from State and Local Sales Taxes?

The great majority of property tax revenue is based on the value of land and buildings, but most states also apply property taxes to certain business equipment, machinery, and supplies, and sometimes also to automobiles. Collectively these taxes are known as “personal property taxes.”

How Can Cities and States Reduce Property Taxes for Homeowners and Renters?

To reduce the cost of property taxes for homeowners and renters, many places offer homestead exemptions, circuit breakers, and deferrals. Such provisions are more cost-effective alternatives to broad tax cuts or tax limitations.

How Can Communities Collect Property Taxes from Exempt Nonprofits?

Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILT or PILOT) programs allow local governments to collect revenue from nonprofits that otherwise would not be contributing to the cost of providing local services.

Learn More

- ITEP (2005). “Capping Assessed Valuation Growth: A Primer.”

- ITEP (2024). Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States. Seventh Edition.

- Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Significant Features of the Property Tax (database).