Almost one in five US tax dollars is collected by a local government, and taxes are the primary way local services are financed, although aid from federal and state governments is also a major revenue source.

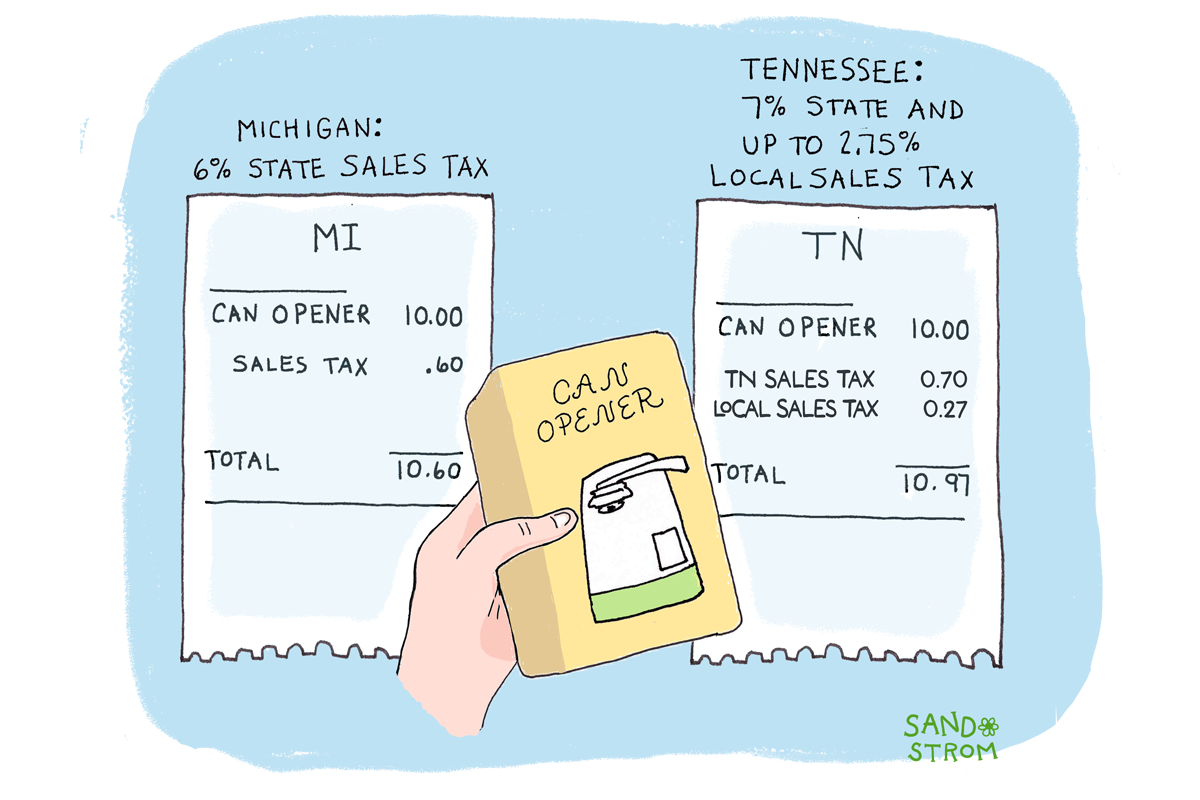

For many localities, property taxes are the largest own-source revenue, but they are not the only option. Depending on the jurisdiction, local governments may have significant revenue from retail sales taxes, personal income taxes, and other taxes and fees.

Tens of thousands of local governments in the United States, from big cities like Los Angeles and New York to rural counties, school districts, and small towns, operate schools, roads, parks, public safety, and other services. To pay for it, they collect roughly $1 trillion in taxes annually and receive another $800 billion in grants from states. But states, not just localities, set many of the rules for local taxes, and sometimes use that authority to undermine local democracy.

What Can Local Governments Tax

The US Constitution does not mention local governments. Like all local powers, local taxing authority is delegated to local governments by the state. In other words, states in their own constitutions and statutes determine the flexibility of local governments to establish taxes and set rates.

Larger cities and counties usually have more expansive taxing powers than smaller towns or rural areas. New York, for example, allows New York City and Yonkers to levy income taxes, but not smaller cities and towns; local sales taxes are more widespread, allowed not just in New York City but in counties and some other cities, with the items and rates constrained by the state.

Sometimes these rules are sensible. Well-designed local tax frameworks promote coordination among local governments and make tax systems simpler and less costly by centralizing administration. They also reduce inefficient and costly tax competition that often make wealthy communities wealthier and poor communities poorer.

A statewide tax is usually less regressive than the same tax would be if levied at the local level. That’s because a local tax allows wealthy communities to keep the taxes raised in that community, while a poorer community may need to impose higher rates to collect the same revenue. On the other hand, local taxes can enhance democracy and accountability by giving a community greater say over how it is taxed and how the money is spent.

States could do more to give local governments the ability to raise new revenue and make their tax codes more progressive. For example, local income taxes increase progressivity and give municipalities more fiscal autonomy and stability – but only 15 states allow them, and sometimes only in certain municipalities.

And local governments often lack the ability to make their property taxes more progressive. If more localities were allowed, they could improve fairness by levying higher property taxes on more expensive properties, by providing a circuit breaker that helps people for whom property taxes exceed a certain share of their income, or by taxing residences at a lower rate than commercial property.

Perhaps most problematic, some states like Georgia have cut local property taxes and replaced the revenue with local-option sales taxes, simultaneously reducing local control and increasing regressivity.

Through TELs and Preemption, States Restrict How Local Governments Raise and Spend Money

Beyond restricting the specific taxes localities may impose, states often enact statutory or constitutional Tax and Expenditure Limits (TELs) to limit how much overall revenue they may collect and spend. For example, Michigan’s constitution grants cities, counties, and other local governments home rule powers but tightly limits overall revenue and expenditures by localities.

Even when local governments work within the narrow confines of existing state law to enact legal revenue measures, states can block them from moving forward or even pre-empt them after the fact. This technique, known as preemption, has been used in recent years to restrict local taxes on soda, plastic bags, and ride-sharing apps. Preemption typically occurs at the urging of corporate lobbyists who have failed to persuade elected officials at the local level. For example, in 2017, soda industry lobbyists spent millions of dollars pushing a destructive California ballot initiative that would have made it nearly impossible to pass any new local taxes unless directly approved by two-thirds of voters; in 2018, state lawmakers banned soda taxes until 2031 and in exchange, the ABA dropped the ballot initiative.

A particularly troubling trend involves majority-white state policymakers undermining the authority of majority-Black local governments to invest in their own communities. In 2020, for example, Alabama preempted an effort by the city of Montgomery to impose a new 1 percent occupational tax to boost public employee salaries and increase funding for schools and other services. The law invalidated Montgomery’s tax and decreed that going forward, localities must get state permission before raising previously established occupational taxes. This measure continued Alabama’s long history of undermining the ability of Black communities to govern themselves.

Related Entries

How Do State Tax and Expenditure Limits Work?

A Tax and Expenditure Limit (TEL) is a formula written into state law or into a state constitution that constrains government revenue and spending. These measures can undermine governmental accountability, degrade essential public services like health care and education, and create inequitable tax burdens.

How Do Real Property Taxes Work?

Property taxes on land and buildings are the oldest and still the largest major revenue source for state and local governments. They fund schools, health care, public safety, and other services. They are collected mostly by cities, counties, school districts, and other types of local government, but states typically make the rules for assessing the value of property and imposing the tax, with major implications for tax fairness and adequacy.

How Can Communities Collect Property Taxes from Exempt Nonprofits?

Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILT or PILOT) programs allow local governments to collect revenue from nonprofits that otherwise would not be contributing to the cost of providing local services.

How Do State and Local Sales Taxes Work?

Sales taxes are the second largest source of revenue for state and local governments. In nearly every state they are an important way we pay for public education, health care, public safety, and other services. But they are also typically the costliest tax for low-income families.

Learn More

- Bean, Lydia, and Maresa Strano. “Punching Down: How States are Suppressing Local Democracy.” New America, 2019.

- Jefferson, Rita. “The (Mostly Untapped) Power of Local Income Taxes.” ITEP, 2025.

- Krupnick, Matt. “‘This industry will stop at nothing’: big soda’s fight to ban taxes on sugary drinks.” The Guardian, November 12, 2022.

- Local Solutions Support Center. “What Is Abusive Preemption and Why Is it a Threat to Democracy?” Accessed April 2025.

- Tharpe, Wesley. “Easing State Restraints on Local Taxing Power Can Strengthen Democracy, Promote Prosperity and Equity.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2023.