A robust corporate income tax ensures that profitable corporations help fund the public services they benefit from, just as working people do.

It’s one of the few progressive taxes available to state policymakers.

Corporations pay income tax because they rely on services that taxes fund. Such services include state education systems for trained workers, transportation systems to move products, and courts to protect property and business transactions. States also grant corporations special privileges, like limited liability for their owners. Corporate income taxes are a way for corporations to contribute to funding services and to pay for the privileges they receive.

It’s not just in-state corporations who pay state corporate income tax. Corporations based elsewhere may still pay tax if they have local employees or facilities or if they work with in-state customers. This makes sense, because whether they have a physical presence in a state, corporations benefit from public services and privileges provided there. The specific legal standard for whether a corporation has sufficient connection in a state to owe tax is known as nexus. Many big corporations operate in every state and so they likely have nexus in most or all of them.

Any tax on corporations ultimately affects the company’s shareholders, executives, staff, or consumers. Research indicates the tax has by far the biggest impact on owners of capital. Since ownership of corporate stock and other assets is highly concentrated among the wealthiest Americans – for example, the top 1 percent hold half of all corporate stock owned by households, while most people own little or none – the corporate income tax is highly progressive.

The fact that the tax is borne by shareholders also means that a state’s corporate income tax is paid largely by out-of-state residents, because most multistate corporations have shareholders around the country and around the world.

But corporate income taxes do not apply to all businesses – only those known in the federal tax code as C corporations. Like the federal government, most states exempt pass-through entities, and most non-publicly held businesses opt to structure themselves that way.

How Corporate Income Taxes Work

States typically use the federal definition of taxable corporate income as a starting point. Taxable income basically means revenue minus expenses, which is to say profit. So the corporate income tax is intended to be a tax on corporate profits.

Special rules apply to companies that do business in multiple states. To mitigate a situation where such corporations pay dozens of state corporate taxes on the same nationwide income, each state has established an apportionment formula to determine its fair share of that income.

Most states require multistate corporations with multiple subsidiaries to pay tax as a single combined entity. Some states, though, still allow each subsidiary to pay separately. The latter approach is known as separate accounting. It allows a multistate corporation to artificially shift its revenues and expenses among subsidiaries so that it can exploit different states’ tax rules. So most states now require a corporation to determine taxable income by adding together the profits of all its subsidiaries into one total – a practice known as combined reporting.

For many years, most states used three factors to figure out what share of a corporation’s income it will tax. Those factors were the percentage of the corporation’s property located in the state (the “property factor,) the percentage of corporate sales made to state residents (the “sales factor”), and the percentage of corporate payroll paid to state residents (the “payroll factor”). Many states now use only the sales factor to figure out what share of a corporation’s income it will tax.

There’s a different approach for apportioning income that is considered “non-business” income, but the basic principle of allocating income to a specific state is much the same.

After determining the income apportionable to a state, the state’s tax rate is applied to determine tax liability. Many states allow credits for activities like research or investment to reduce tax liability. Recognizing that some corporations have gotten very good at avoiding taxes, some states require every corporation to pay a minimum tax.

State corporate taxes are deductible on federal returns. That means that for every dollar it pays in tax, a corporation receives up to 21 percent of that amount back from the federal government in the form of reduced federal taxes. That means that federal deductibility reduces the effective difference between states with high and low corporate tax rates.

Conventional wisdom once held that corporate profits were taxed twice, once at the corporate level and then again when distributed to shareholders, but this is no longer the case. Not all corporate profits are distributed, and even when they are, most corporate stocks today are held in tax-free retirement accounts, pension funds, or nonprofit endowments.

Revenue

Corporate profits and thus state corporate income tax collections rise and fall with the economy. The long-term trajectory of state corporate income taxes is also uncertain. State corporate taxes do not raise as much revenue as they did half a century ago, partly because US businesses increasingly organize as partnerships or S Corporations, partly because the proliferation of tax loopholes at the federal level is being passed through to state governments, and partly because corporations have gotten better at avoiding state corporate taxes.

More recently, soaring corporate profits and crackdowns on tax avoidance schemes have reversed the decline. State policymakers seeking to make their tax codes fairer for families can learn from recent trends and reform corporate taxes, close loopholes, and reduce avoidance.

Related Entries

How Do State and Local Personal Income Taxes Work?

The personal income tax helps fund public education, health care, public safety and other public services provided by state and local governments. If well-designed, it is the fairest major revenue source available to states because it is levied broadly across the economy while protecting the poorest households.

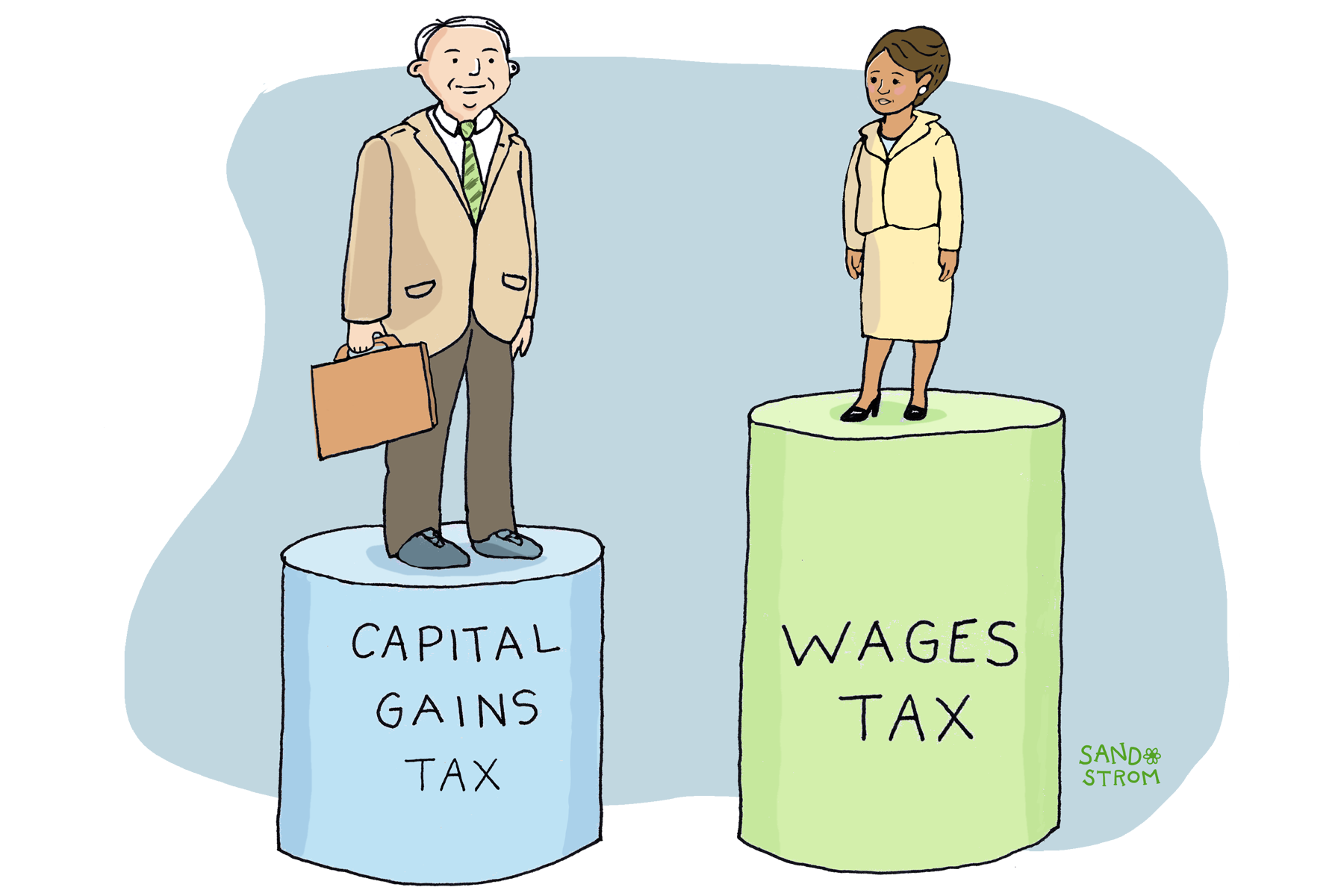

How Do States Tax Investment Income?

State personal income taxes apply not just to wages and salaries but also earnings on investments, like stocks and bonds. Most investments are held by wealthy people, so when states tax investment income at a lower rate than wages, high-income households pay tax at lower rates than middle-income households.

Do Tax Cuts Fuel Economic Growth?

Tax policy is an important economic tool, but claims that tax changes will affect a state’s economy are often overstated. Such overstated claims are particularly common in discussions of taxes on wealthy individuals and profitable corporations, so careful assessment of such claims is an important part of shaping adequate and equitable revenue streams.

Learn More

- Burman, Leonard E., Kimberly A. Clausing, and Lydia Austin (2017). “Is U.S. Corporate Income Double-Taxed?” National Tax Journal 70:3.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (accessed April 2025). “State and Local Revenue Options for Advancing a Brighter Future: Corporate Income Tax and Other Business Taxes.”

- Davis, Aidan, Matthew Gardner, and Richard Phillips (2017). “3 Percent and Dropping: State Corporate Tax Avoidance in the Fortune 500, 2008 to 2015.” ITEP.

- Davis, Carl, Matthew Gardner, and Michael Mazerov (2025). “A Revenue Analysis of Worldwide Combined Reporting in the States.” ITEP.

- Suárez Serrato, Juan Carlos, and Owen M. Zidar (2023). “Who Benefits from State Corporate Tax Cuts? A Local Labor Market Approach with Heterogeneous Firms: Further Results.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.