Most businesses are not liable for corporate income tax on their profits. Instead, federal and state tax laws allow them to choose a structure such as partnerships, sole proprietorships, and S-corporations under which their profits are passed through to their owners for taxation.

These “pass-through entities” benefit from state-funded services like schools, infrastructure, and public safety, and their owners are generally wealthy, so taxing them fairly – at a minimum ensuring that pass-through income is taxed at the same rate as wages – is essential to a sound and equitable revenue system.

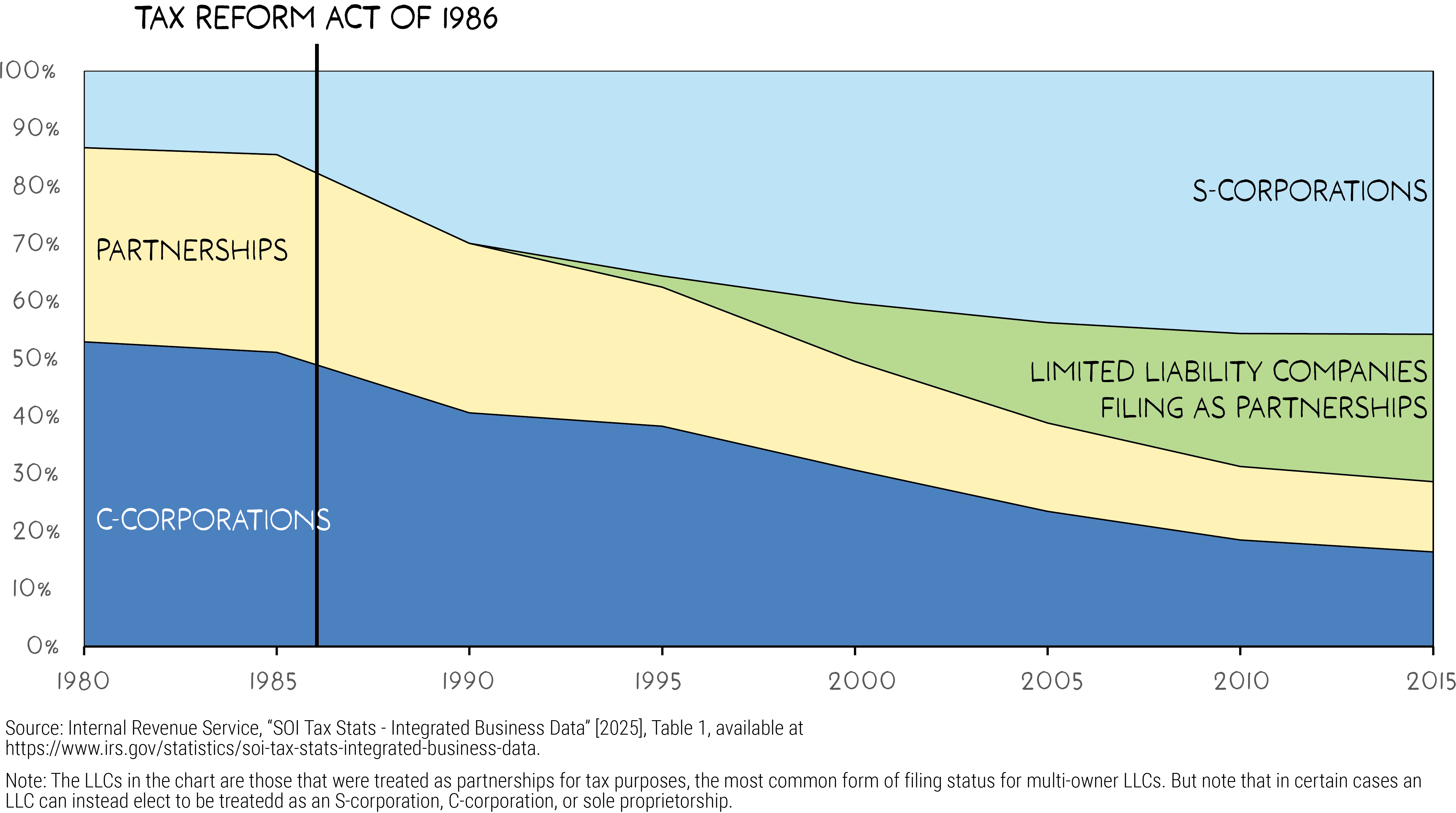

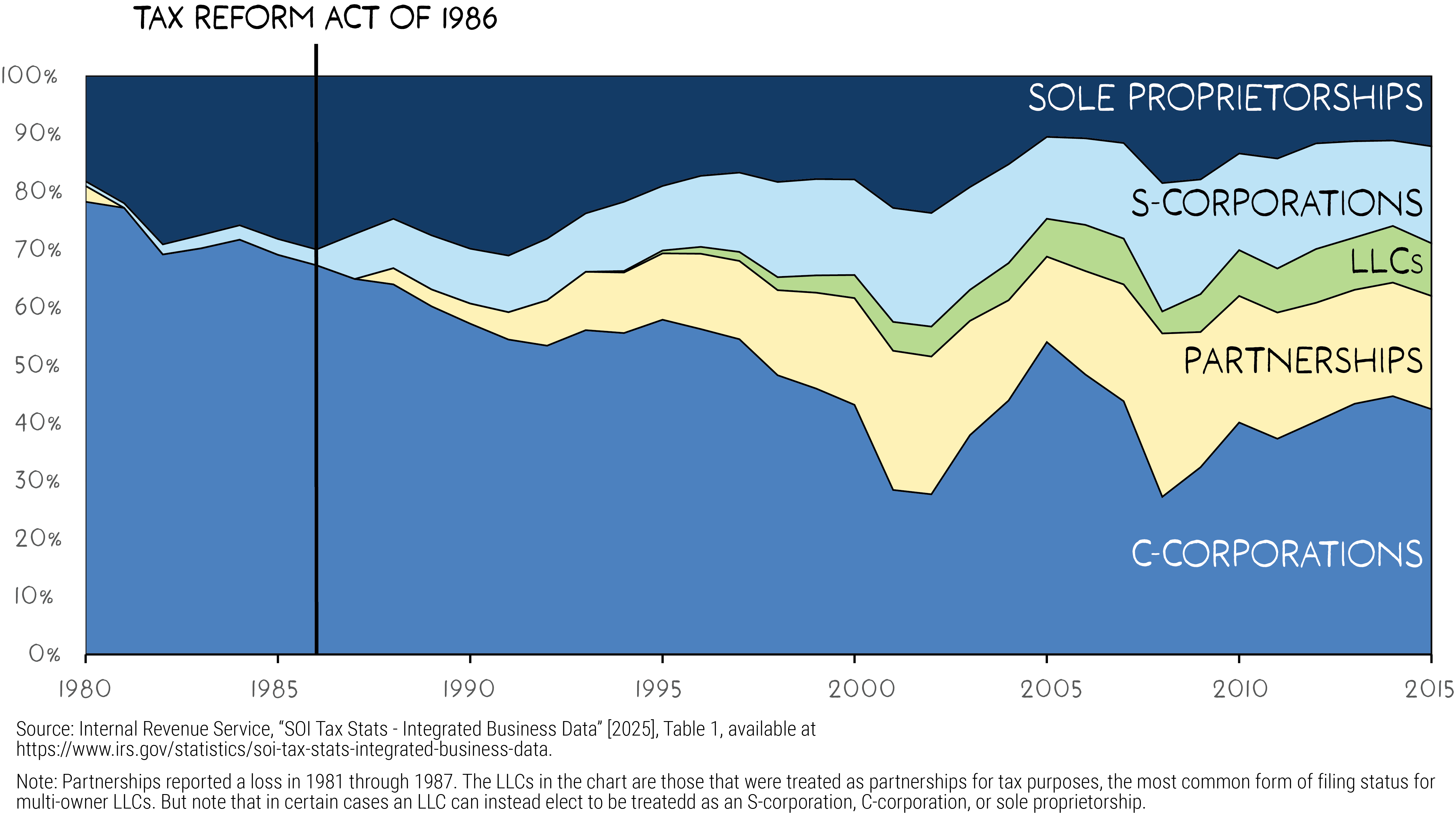

Until the 1980s, most U.S. businesses, representing nearly all the nation’s business profits, were structured as C-corporations and therefore were subject to federal and state corporate income tax. But changes to federal tax law created incentives for businesses to file taxes not as C corporations, but instead as entities whose profits are passed through to their owners’ personal income tax. Pass-through entities include S-corporations, partnerships, limited liability companies, and sole proprietorships. Nearly all states with income taxes conform to those federal rules.

Today, most U.S. businesses are pass-through entities (PTEs), and these entities account for more than half of business income.

Figure 1: Distribution of US Business Entity Types, 1980-2015

Figure 2: Distribution of US Business Profits by Type of Entity, 1980-2015

Federal tax law identifies three different sets of rules under which a business can be taxed as a pass-through entity.

- An S-corporation cannot have more than 100 shareholders, so they cannot be publicly traded on a stock exchange. In most respects, S-corporations enjoy similar benefits as publicly traded C-corporations, such as protection from liability for their owners.

- A partnership has partners rather than shareholders. Some partnerships, like big law firms or accounting firms, have hundreds or even thousands of partners. Many partnerships are also “limited liability companies” or “limited liability partnerships,” giving the partners similar legal protections as enjoyed by corporations.

- A sole proprietorship is owned and operated by a single individual. A freelancer or gig worker might be a sole proprietor, but so too might be a business owner with many employees and high profits.

In the case of a sole proprietorship (a business with one owner), the business’s net income is calculated and reported on the individual owner’s personal income tax form. With multiple owners and investors, as in a partnership or S-corporation, the net income reported on each owner’s tax return depends on that owner’s ownership percentage.

Pass-through businesses receive tax benefits that C-corporations do not receive. One is not having to pay tax at the corporate level. Another is that in some states, the corporate income tax rate is higher than the personal income tax rate. For example, in Alabama a C-corporation pays corporate income at a rate of 6.5 percent, but a pass-through pays nothing at the entity level, and its Alabama owners pay income tax at a top rate of 5 percent. So that difference of 1.5 percentage points saves them at least $15 on every $1,000 of profits. Even when the personal income tax rate is higher than the corporate rate, however, the fact that PTEs avoid corporate-level tax tends to make their tax treatment more favorable.

Pass-through entities do not escape state entity-level taxation of their profits everywhere. Some states apply their corporate income tax to some PTEs, or they have special taxes on those profits. And some states levy other kinds of taxes, like gross receipts taxes or margins taxes, on all businesses regardless of federal tax status. These taxes ensure that PTEs, like C-corporations, contribute to the cost of public services like schools and infrastructure that help all businesses thrive.

Although the average pass-through entity is smaller than the average C-corporation, many are still very large and profitable. The media conglomerate Bloomberg, with 20,000 employees, is a limited partnership. The financial services firm Fidelity Investments is an LLC. And pass-through owners tend to have high incomes. In fact, pass-through income is more highly concentrated among high-income households than any other source of taxable income. The highest-income 0.01 percent of the population receives 35 percent of its income from pass-through entities, compared with just 9 percent for the bottom 90 percent of the population.

A different kind of tax on pass-through entities has been enacted by many states in recent years, not to raise revenue, but to help owners and investors who live in those states reduce their federal taxes. These PTE taxes are allowable as a federal tax deduction and therefore reduce owners’ federal net income, and hence their federal taxes. States then rebate the PTE tax to owners in the form of an offsetting credit, so their net state tax liability is unaffected. Most of these are elective taxes; pass-through entities typically are allowed to pay the tax if their owners want to take advantage of this mechanism, but they aren’t required to pay it if they choose not to. This mechanism is known as a “SALT cap workaround” because it lets business owners avoid a federal cap on the deductibility of state and local taxes (SALT) from personal income tax. It almost entirely benefits wealthy people; in Maryland for example, 80 percent of the claims are from the wealthiest 1.7 percent of tax filers, those with income over $500,000.

The federal government offers a tax break to many pass-through entities, and some states also tax them at favorable rates. This means that pass-through entity owners and investors pay lower taxes than wage earners. Tax breaks for pass-through entities are racially inequitable because generations of racial discrimination have left Black and Hispanic households with less access to capital and therefore lower rates of business ownership. A U.S. Treasury Department study found that 90 percent of the benefit from the federal tax break for pass-through entity owners and investors accrued to a small number of white households. Hispanic and Black households only received 5 percent and 2 percent of the benefit, respectively. Fairness would suggest that states should ensure both that personal income from pass-through businesses is taxed at the same rate as personal income from wages and also consider entity-level taxes.

Related Entries

How Do State Corporate Income Taxes Work?

A robust corporate income tax ensures that profitable corporations help fund the public services they benefit from, just as working people do. It’s one of the few progressive taxes available to state policymakers.

How Do State and Local Personal Income Taxes Work?

The personal income tax funds public education, health care, public safety, and other public services provided by state and local governments. If well-designed, it is the fairest major revenue source available to states.

Learn More

- Cronin, Julie-Anne, Portia DeFilippes, and Robin Fisher (2023). “Tax Expenditures by Race and Hispanic Ethnicity: An Application of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Race and Hispanic Ethnicity Imputation.”

- ITEP (2024). Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States. Seventh Edition.

- Joint Committee on Taxation (2023). “Present Law and Background on the Income Taxation of High Income and High Wealth Taxpayers.”

- Mitchell, David S. (2024). “What the Research Says About Taxing Pass-Through Businesses.” Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

- Tax Law Center at NYU Law (accessed July 2025). “SALT Workarounds.”