Most states that collect income taxes allow taxpayers to claim itemized deductions, which are tax breaks for items such as charitable donations, mortgage interest, medical expenses, and property taxes.

These deductions reduce revenues that could otherwise be used for services like schools and health care, and they mostly benefit wealthy families. Because they are so skewed and ineffective, many states either limit itemized deductions or forgo them altogether.

The Basic Choice: Standard or Itemized

When filing federal and state income taxes, taxpayers often face a choice. They can claim a standard deduction, or they can itemize, which means adding up specific expenses like mortgage interest and charitable gifts to get a bigger tax break.

This choice sounds straightforward, but it creates an immediate problem. Only families with substantial expenses in the right categories benefit from itemizing. In a state with a $17,000 standard deduction, for example, a family that donates $5,000 to charity and pays $10,000 in mortgage interest and property taxes lacks enough total deductions to make itemizing worthwhile. Meanwhile, a family that with $15,000 in property taxes, $20,000 in mortgage interest payments, and $10,000 in charitable donations will see significant tax savings from itemizing.

In a few states, there’s an additional complication: A household that fails to itemize on its federal return is barred from itemizing on its state return, even if doing so would give it a lower tax bill. This can happen if the household’s itemized deductions are less than the federal standard deduction but greater than the state standard deduction. This provision further concentrates the benefits of itemization among higher-income taxpayers.

Who Benefits

Itemized deductions mostly benefit the wealthy. Among households earning under $100,000, fewer than 6 percent claim itemized deductions on their federal returns. But nearly half of households earning over $200,000 itemize, and more than 70 percent of millionaires do.

Why? Wealthy families are more likely to own expensive homes, generating large mortgage interest and property tax payments. They also have more disposable income for charitable giving.

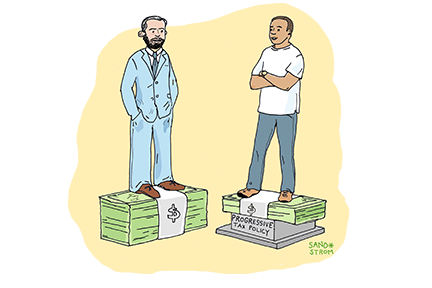

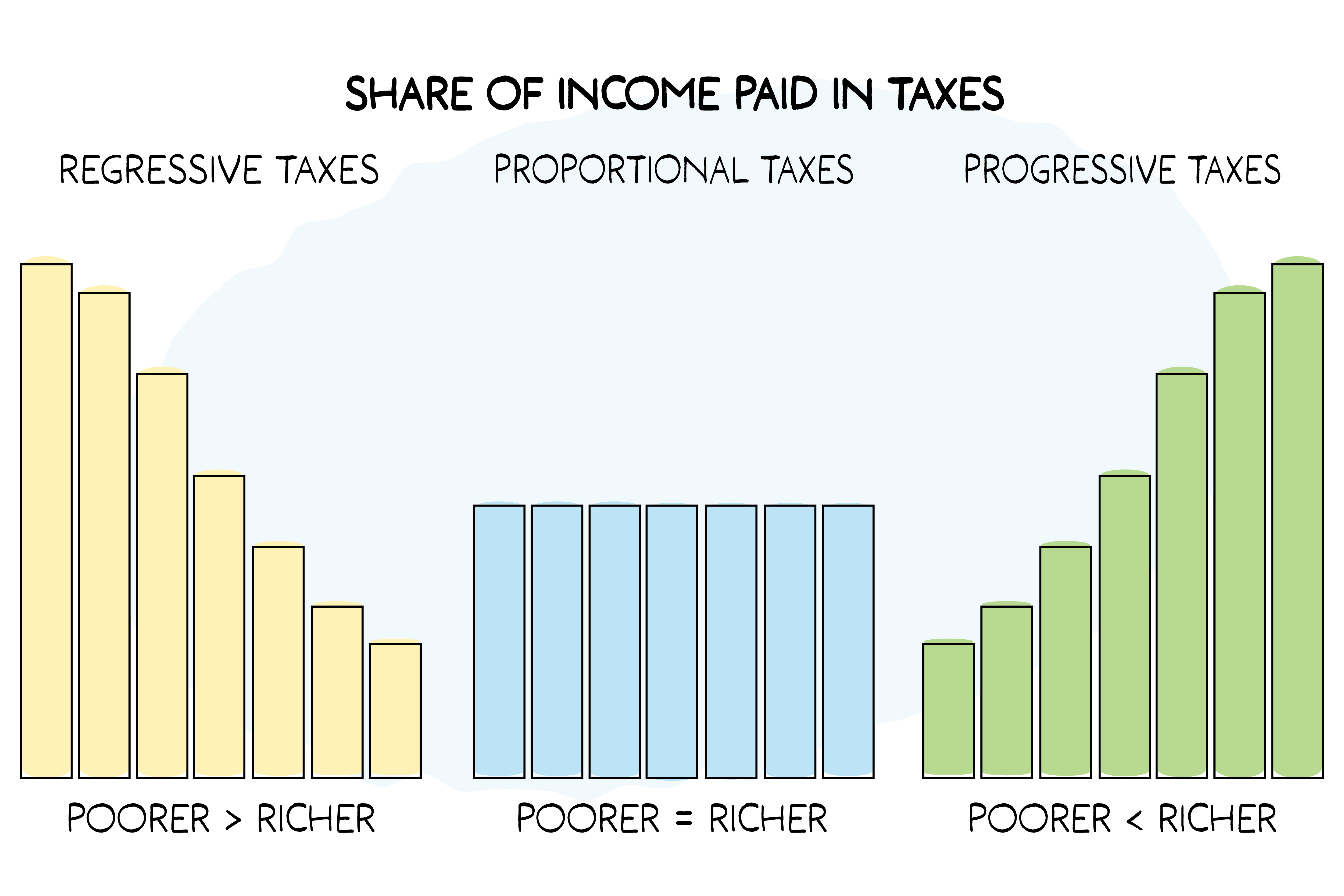

Moreover, in states with graduated-rate income taxes, families in higher tax brackets get a bigger tax break for each dollar deducted than do middle-income families.

Consider two taxpayers: one earning $50,000 who faces a 5 percent state tax rate, and another earning $500,000 who faces an 8 percent rate. If both deduct $1,000 in charitable giving, the first taxpayer saves $50 in state taxes while the second saves $80. The same deduction provides more value to the person who needs it less. As a result, the great majority of the dollar benefits from itemization accrue to high-income households.

A 2020 ITEP analysis of itemized deductions in Maryland found that about 70 percent of the tax cuts from itemized deductions flowed to the top 20 percent of earners. The average tax cut for the top 1 percent of taxpayers was more than $4,000, while most families got no benefit at all.

That same analysis also showed that Black- and Hispanic-headed households were much less likely than other households to benefit from itemization. That’s because, as a legacy of historic patterns of economic discrimination and housing segregation, Black and Hispanic households on average have lower incomes and lower homeownership rates, so they benefit relatively little from the ability to itemize.

Itemized Deductions as Incentives

Supporters often defend itemized deductions as incentives for certain behaviors. They argue that the charitable deduction encourages giving, the mortgage interest deduction promotes homeownership, and the property tax deduction might make it politically easier for local governments to raise revenue.

Unfortunately, itemized deductions are deeply flawed tools for achieving those goals. The great majority of households don’t itemize and are therefore unaffected by itemized deductions. For those who benefit, because state tax rates are only a few percentage points, the incentive effect is modest. A taxpayer facing a 7 percent state tax rate only saves seven cents for every dollar donated to charity.

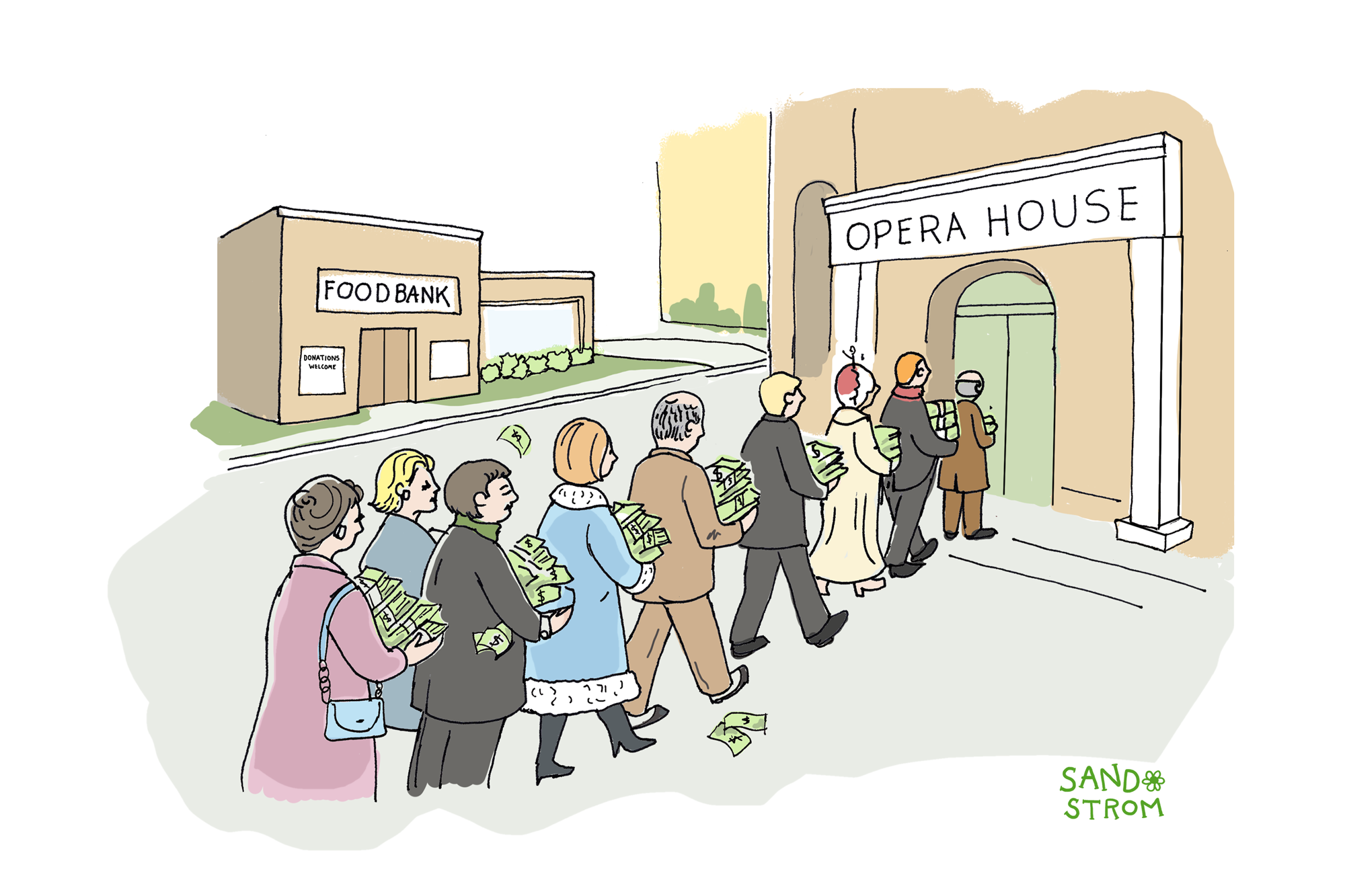

The wealthier taxpayers who do benefit tend to direct their donations to charities that they appreciate. Museums and opera houses often get more of these contributions than food banks and homeless shelters.

The mortgage interest deduction not only fails to benefit those prospective homeowners most in need of assistance (those with low incomes), but it may work against the goal of homeownership itself. Economic research suggests that the deduction makes higher-income homebuyers willing to pay more, driving up house prices and making homes less affordable for first-time buyers who aren’t itemizers. Meanwhile, the deduction is available for vacation homes too, which has nothing to do with encouraging homeownership. In short, the mortgage interest deduction is perhaps the single most ineffective possible way for states to support housing affordability and homeownership.

Limiting Itemized Deductions

Recognizing that itemized deductions are skewed and ineffective, states and the federal government have enacted a variety of limits. One strategy is to limit itemized deductions, either as a dollar amount or as a percentage of income, or to phase them out as income rises. Another is to allow only deductions that exceed a certain percentage of income. Yet another is to convert itemized deductions to tax credits so they benefit all itemizers equally. The most effective approach is to disallow itemized deductions entirely.

Related Entries

How Do State and Local Personal Income Taxes Work?

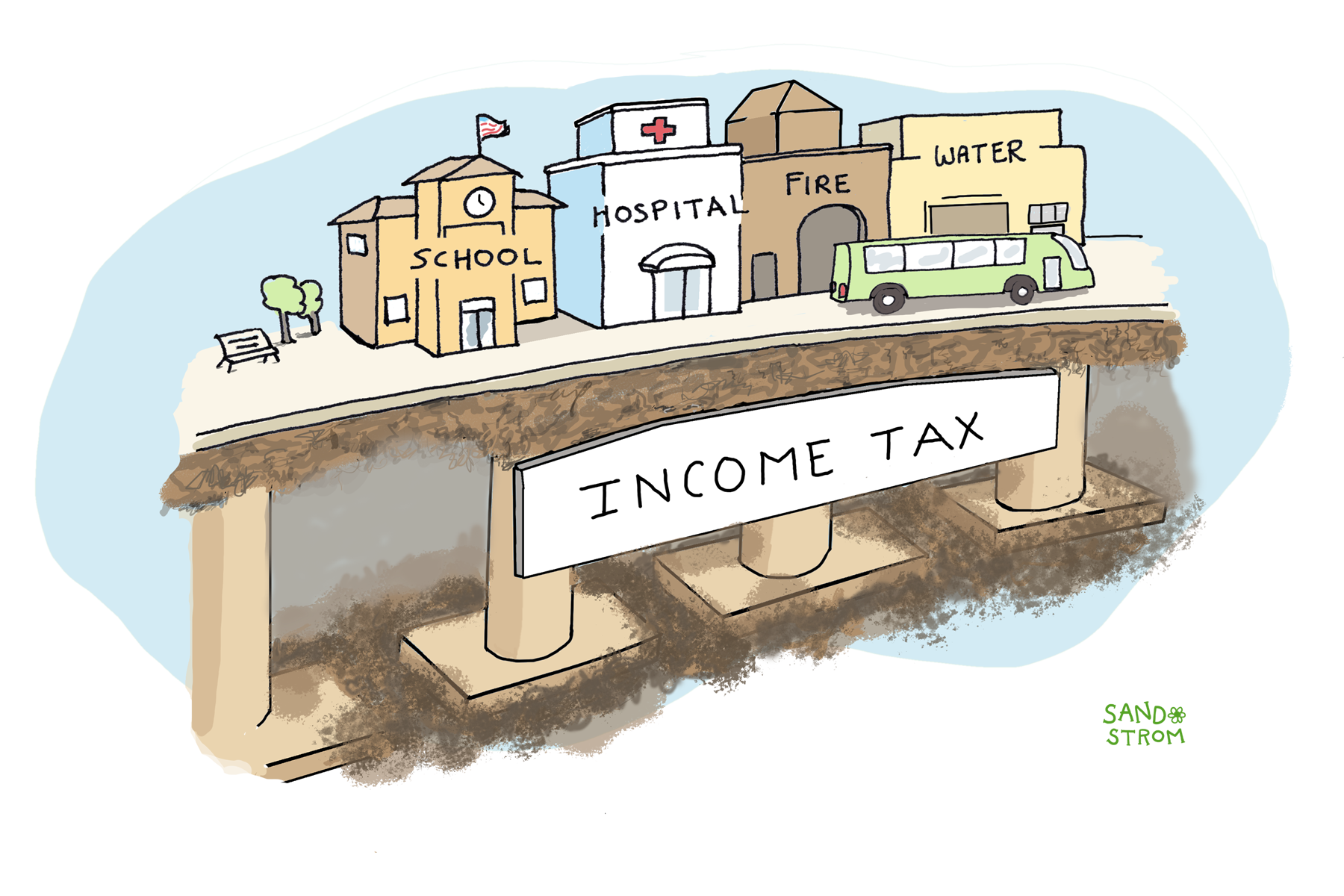

The personal income tax funds public education, health care, public safety, and other public services provided by state and local governments. If well-designed, it is the fairest major revenue source available to states.

How Do State and Local Tax Systems Affect Racial Justice?

State and local tax codes have the potential to either narrow or widen racial inequality created by historical and current injustices in public policy and in broader society. In general, tax codes that are more progressive across the economic spectrum do more to narrow racial inequality, while regressive tax policies exacerbate it.

Why should states and localities have progressive tax systems?

A tax system cannot be described as fair unless it is progressive, but that’s not the only reason why states should tax upper-income people at higher rates than those with lower incomes.

Progressive state tax codes raise more revenue for public services, improve the government’s relationship with residents, reduce poverty, and advance racial equity.

Learn More

- Davis, Carl (2020). State Itemized Deductions: Surveying the Landscape, Exploring Reforms. ITEP.

- O’Neill, Dylan Grundman, and Nick Johnson (2025). “States Should Move Quickly to Chart Their Own Course on SALT Deductions.” ITEP.

- Sommer, Kamila, and Paul Sullivan (2018). ”Implications of US Tax Policy for House Prices, Rents, and Homeownership.“ American Economic Review 108 (2): 241–74.