Last week, IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig vowed to work with Congress to explore how the federal tax system contributes to the racial wealth gap. There are at least two ways this can happen: tax policies enacted by Congress and IRS enforcement of these policies.

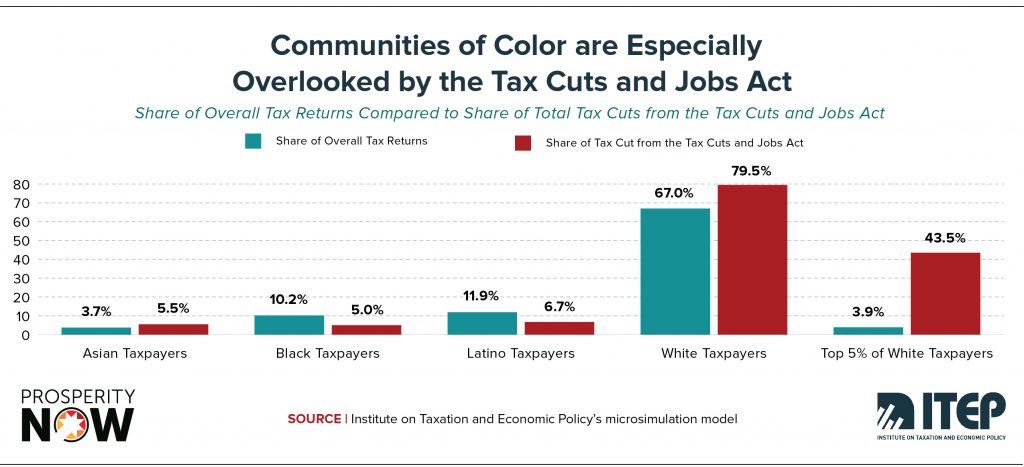

Scholarship already exists on this, including a 2018 report by ITEP and Prosperity Now, which revealed that the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act exacerbated the racial wealth divide by funneling 80 percent of its benefits to white households. In 2018, white households received an average tax cut of $2,020, Hispanic households received $970 and Black households received $840.

Perhaps it was not lawmakers’ express intent to pass more wealth to white households, but intent is not the same as effect. If the IRS is truly committed to exploring how the tax system contributes to the racial wealth gap, it should collect better race-based data and produce analyses disaggregated by race so policymakers fully grasp the impact the tax system has (and any proposal would have) on people of all races and can respond with policies to remedy inequities.

For the last four decades, the gap between rich and poor has grown wider for myriad reasons, including coordinated attacks on workers’ rights to collectively bargain, corporations passing more of their profits to shareholders instead of rank-and-file workers, and tax policies that treat income from wealth more favorably than earned income. Black families remain at an economic disadvantage due to the legacy of public policies and social practices that sowed economic divisions by boosting the white middle class and denying Black families equal access to educational, homeownership and job opportunities. A typical white family’s wealth of $171,000 is 10 times more than a typical Black family’s wealth of $17,150.

Tax policy alone cannot reverse systemic racism that has contributed to grossly unequal economic outcomes for Black and brown people, but it can be part of the solution. Unfortunately, Congress has hamstrung the IRS in ways that favor corporations and wealthy, white households.

Disinformation campaigns over the last couple of decades have wrongly cast the IRS as a public enemy, making it easier for anti-tax advocates and their political allies to continually strip funding from the critical agency. Funding erosion has left the IRS ill-equipped to enforce tax payments to the tune of billions a year by some estimates. A recent report from the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration found that more than 879,000 households with income of $100,000 or more didn’t file tax returns between 2014 and 2016 and owe more than $45 billion in federal taxes. And a Congressional Budget Office report released Wednesday confirms that IRS budget cuts deprive the U.S. Treasury of revenue and benefit the rich. Lax tax enforcement also jeopardizes the nation’s ability to raise needed revenue for social services, public health, food safety, education and other domestic programs.

IRS funding woes have resulted in racist enforcement of tax laws.

In the fall of 2019, the IRS admitted that it audits low-income people at a higher rate than affluent families because “it’s easier,” ( they don’t have the resources to contest), and it can’t aggressively go after tax-avoiding higher-income households until Congress restores funding. The agency lacks enough staff expertise to unravel complex tax schemes employed by wealthy people whose income comes from sources other than a W-2. Instead, taxpayers who claim the Earned Income Tax Credit are more likely to be audited, as ProPublica has reported. A deeper look at that data revealed that race and poverty combined are a determining factor in the likelihood of being audited. Michael Harriot wrote in The Root:

…the places with low audit rates aren’t marked by wealth. Some of the most diverse, wealthiest counties in America (Arlington, Va., and Howard County, Md., for instance) are typified by normal audit rates. It is only when you factor in poverty and race that you get the high audit rates. Nearly every place where there are pockets of Black poverty has become an IRS target for audits. In fact, when The Root did a county-by-county mapping of the non-white population, it was stunning how closely it resembles the places where the IRS audits more.

Aggressively auditing struggling working families who qualify for the EITC has a chilling effect. The CBO report released this week notes that those who are audited are “less likely to claim the EITC or file taxes for a refund in subsequent years than (are) similar taxpayers who (are) not audited.” Disincentivizing EITC claims is particularly egregious considering the IRS has simultaneously failed to penalize wealthy tax cheats.

The system, by design, is rigged.

Congress has long bowed to special interests who use racially divisive tactics in support of their damaging narrative about the role of government and taxes. Attacks on the IRS and tax collections have enabled deliberate erosion of the IRS’s budget and federal tax policies (such as the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act), which diminish rich people’s tax obligations and boost their after-tax income.

The nation’s lack of significant investment in all its people and transfer of wealth to the elite few mean that far too many of the rest of us, a disproportionate share of whom are Black, brown and Native, are one or two paychecks away from missing a housing payment or having money for food. The economic fallout due to COVID-19 and ongoing protests regarding police violence are further exposing harsh truths about the devastating social and economic consequences of systemic racism, including the racial wealth gap. It’s a positive step that the IRS commissioner believes the agency should address this pressing social challenge. Tax policy alone cannot fix the racial wealth gap, but it can and should be part of the solution.