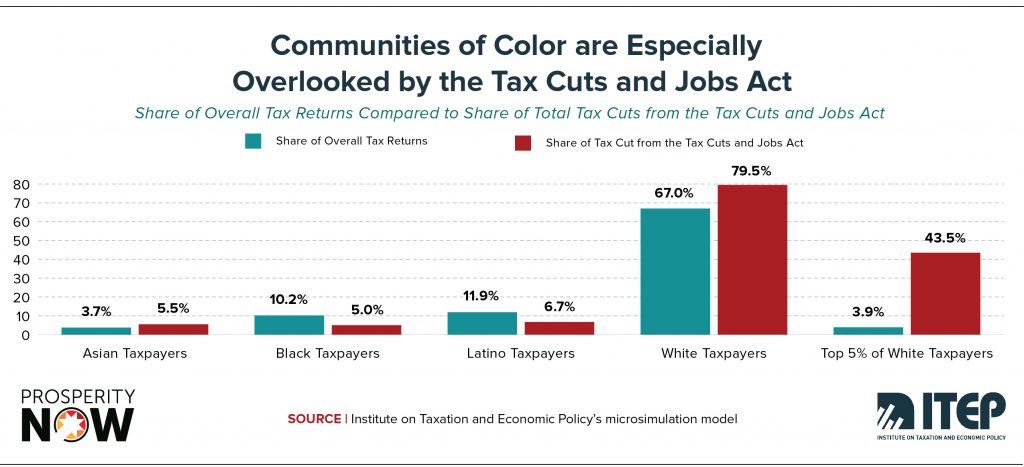

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) recently worked with Prosperity Now, an organization committed to closing the racial wealth gap, to produce a report that reveals how the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act mostly benefited white families. It is well known that the bulk of the federal tax cuts flowed to the highest-earning households, who received the largest tax cut both in terms of real dollars and also as a share of income. [1] But as our analysis in the report (Race, Wealth and Taxes: How the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Supercharges the Racial Wealth Gap) reveals, solely examining the tax law in the context of class misses a bigger-picture story about how the nation’s public policies not only perpetuate widening income and wealth inequality, they also preserve historical and current injustices that continue to allow white communities to build wealth while denying (or suppressing) the same level of opportunity to communities of color. [2]

For nearly four decades, ITEP has published research to raise awareness of how tax policies affect the federal and state governments’ ability to raise revenue and fund critical programs and services. Using our analytic model, ITEP researchers produce distributional analyses, which show how current and proposed tax policies affect people across the economic spectrum. Our work has always been driven by the belief that public discourse about tax policy should focus not only on budgetary implications but also on how governments can raise adequate revenue in a fair and sustainable way.

Over the last decade, we expanded our research to examine the role tax policy plays in widening economic inequality. Growing concentration of income and wealth in the hands of the elite few is due to numerous factors, including: corporations prioritizing shareholders’ interests; fewer workers having collective bargaining rights; deregulation of financial and other industries; and policies that tax income earned from work at higher rates than income derived from investments. The recent federal tax law further tilted the scales in favor of the wealthy.[3] And state tax codes have long exacerbated income inequality by capturing a greater proportion of taxes as a share of income from their lowest-income residents than from their richest.[4]

While ITEP has produced quantitative and qualitative research on class-based tax inequities, we, until recently, have ignored how tax policies affect communities based on race. Race, Wealth and Taxes is our first foray into disaggregating data by race from our model-based distributional analyses.[5] We approached this joint project with the intention of learning and also ensuring more of our future work examines tax policy through a racial equity lens. A continued “colorblind” approach to tax and economic policies is outmoded and ineffective. Acknowledging the disparate impact tax policies have based on race is paramount to building truly equitable and sustainable tax systems. So if, for example, ITEP produces research that explores how state tax systems are giving the wealthy a pass on paying their fair share while demanding more of low-income taxpayers, so, too, must we show how states tax communities of color at higher rates, effectively stripping them of income and wealth. Similarly, if ITEP publishes research that examines how federal tax laws are funneling more wealth to the highest-income households, it must recognize how this not only maintains income inequality but also worsens the racial income and wealth divides.

As we have acknowledged, the racially differential impacts of tax policies are not solely a result of tax policies themselves. Tax policy choices are both a symptom of and contributor to broader injustices. This paper by no means intends to describe in depth all the myriad ways in which systemic racism has contributed to racial income and wealth gaps. We cite studies by multiple scholars and institutions that have done the hard work of examining historic and current data and trends to document how our nation’s institutions have contributed to racial income and wealth inequality. At the end of this paper, we include a brief list of recommended reading.

The Lasting Legacy of the Slave Tax

Numerous historical examples of explicitly racist tax policies exist, and many continue to impact state and local tax systems today. It is impossible to document every example of how policy makers have used tax codes to advantage whites and disadvantage people of color, but the report Advancing Racial Equity with State Tax Policy from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities provides an accounting of several historical examples, and this paper highlights a few others.[6]

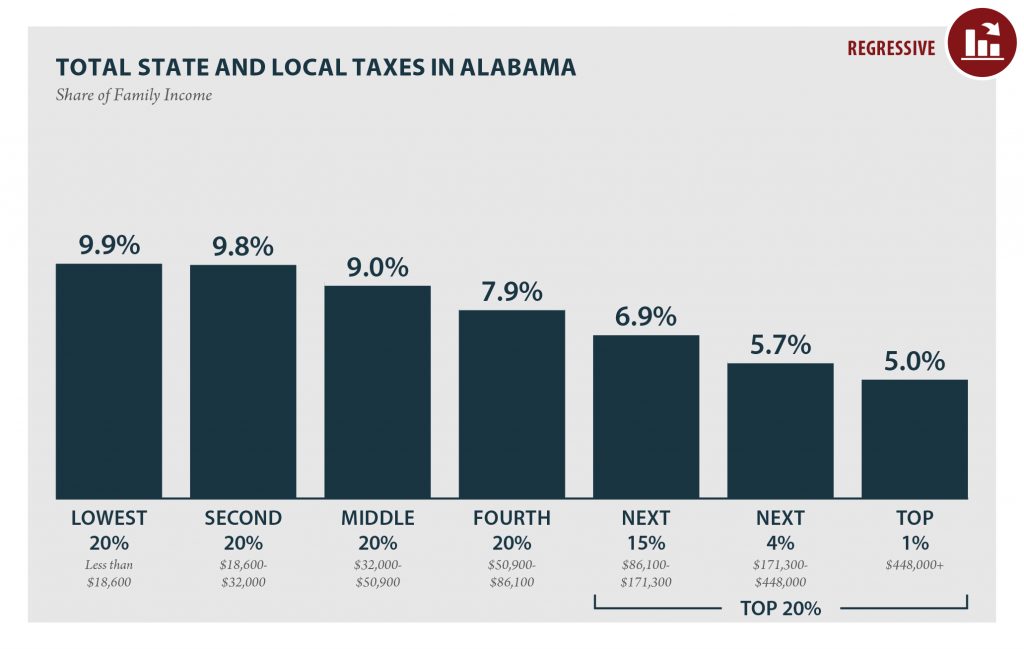

During chattel slavery, state governments collected a “slave tax,” that is, a tax on the property value of a human being, through the end of the Civil War.[7] The federal government also collected slave taxes in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In addition to the moral repugnancy of levying a tax on the value of a person, slave taxes also grossly distorted state budgets. Scholars estimate that taxes on enslaved people accounted for 30 to 60 percent of states’ budgets.[8] In Alabama, slave taxes helped keep property taxes low. This meant white landowners paid virtually no taxes, allowing them to continually accrue and transfer wealth. After emancipation, efforts to increase property taxes to supplant lost revenue were met with forceful backlash. Alabama lawmakers ultimately enshrined in the state constitution property tax caps, which stand to this day. These caps, combined with a virtually flat income tax, have forced Alabama to rely heavily on sales and excise taxes. Reliance on regressive consumption taxes contributes to Alabama having the 18th most unfair tax system in the country: The poorest 20 percent of taxpayers contribute nearly twice as large a share of their income in taxes than the wealthiest 1 percent.[9] A cause of Alabama’s upside-down tax code can be traced back to the 1874 decision to cap property taxes, but the effect is the same now as it was then—the protection of wealthy whites at the expense of wealth growth and investments for everyone else, especially communities of color.

Housing, Education and Criminal Justice Policies Affect Wealth-Building Opportunities

Housing, education and criminal justice policies, to name a few, have led to gross disparities in outcomes for communities of color and advantages for white communities. The roots of this are hardly a mysterious phenomenon. Confiscation of indigenous people’s land and transferring it for free to white immigrants, the internment of Japanese Americans and government seizure of their property during World War II and restricting Black home buyers to deliberately devalued neighborhoods through redlining all contributed to white wealth accumulation and depressed the ability of communities of color to acquire wealth on the same scale.[10] From 1934 to 1968, the Federal Housing Administration’s underwriting practices resulted in families of color receiving just two percent of government-backed mortgages[11] and pushed black families into so-called “land contracts” that required usurious payments.[12] These practices caused a disproportionately high percentage of the limited Black families who acquired homes to eventually lose them. Many either lost wealth-building opportunities or were stripped of their wealth via a system designed to do just that. Racial disparities in homeownership rates are currently the largest driver of the racial wealth gap.[13] According to the latest available data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Black and Latinx households persistently have less household wealth than their white counterparts regardless of educational attainment.[14]

The persistent devaluation of property in Black neighborhoods has a direct effect on educational opportunities.[15] Heavy reliance on local property taxes to fund education has created a K-12 educational system in which one’s zip code is a key indicator of educational outcomes. More than 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education, public schools are more segregated than before.[16] School districts that serve low-income students receive less funding from local property taxes due to depressed home values, which means they have fewer resources to invest in students, resulting in poorer educational outcomes. Unequal education also has lasting effects when it comes to post-secondary education, job opportunities and involvement with the criminal justice system.

Mass incarceration of people of color has pernicious roots. The 13th Amendment essentially ended one form of slavery for another. Shortly after emancipation, the criminal justice system incarcerated men, mostly poor and Black, for alleged crimes as menial as vagrancy, forcing them to labor for free in mines, railroads, fields and other industries—building white wealth at little cost to that community. Continued over-policing in communities of color and biases in sentencing laws have led to the mass incarceration of Black and Latinx individuals, particularly working-age men. While illicit substance use, for example, is roughly the same across racial groups, Black people are much more likely to be arrested for drug use or possession. Further, individuals of color connected to the criminal justice system face considerable barriers to job opportunities post incarceration. White men with a criminal record are more likely to be granted a foot in the door than Black men with no arrest record. This strips families and communities of vital human resources.[17]

Tax Policy Is Part of the Solution

The tax code is both a symptom of and instrument of systemic racism. We cannot simply state that white communities have more income and wealth than communities of color without recognizing the long history of social and economic policies that lead to this divide. Dismantling policies that unfairly perpetuate white economic advantage requires an understanding of the forces that created the advantages and the current policies that ingrain them. The tax code will not be the panacea that ends racial disparities in the United States, and a race equity lens alone will not ensure a progressive and sustainable tax code for all. But if a majority in this nation are truly invested in securing public policies that create a more inclusive society, we must recognize that tax policy contributes to pernicious race and class divisions.

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy has always relied on evidence to inform the tax policy debate and provide policy recommendations. The evidence is clear that a color-blind approach to the tax code is impossible and insufficient to achieve our goal of equitable and sustainable revenue sources. Thus, we have committed ourselves to addressing the implications of race, alongside income, on who pays taxes in America.

In addition to what is cited in the endnotes, please consider the following list of additional reading and listening.

Additional Reading and Listening

American Taxation American Slavery, Robin L. Einhorn

The Ever-Growing Gap: Failing to Address the Status Quo Will Drive the Racial Wealth Divide for Centuries to Come, Chuck Collins, Dedrick Asante-Muhammed, Emanuel Nieves and Josh Hoxie

Hidden Rules of Race are Embedded in the New Tax Law, Darrick Hamilton and Michael Linden

Racial Taxation: Schools, Segregation, and Taxpayer Citizenship 1869-1973, Camille Walsh

Taxing the Poor: Doing Damage to the Truly Disadvantaged, Katherine S. Newman and Rourke L. O’Brien

Who Benefits from the Tax Code?, PolicyLink

School Segregation in 2018 with Nikole Hannah-Jones, Why is This Happening? with Chris Hayes

The 1619 Project, New York Times, Nikole Hannah-Jones, et al.

Their Family Bought Land One Generation After Slavery. The Reels Brothers Spent Eight Years in Jail for Refusing to Leave It., Lizzie Presser

Opportunity Zones Have Nothing to Do with Reparations, Except … , Jenice R. Robinson

The Great Land Robbery, Vann R. Newkirk II

[1] Richard Phillips. “Five Things to Know on the One-Year Anniversary of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, December 17, 2018. https://itep.org/five-things-to-know-on-the-one-year-anniversary-of-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act/.

[2] Meg Wiehe, Jeremie Greer, David Newville and Emanuel Nieves. “Race, Wealth and Taxes: How the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Supercharges the Racial Wealth Divide,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and Prosperity Now, October 11, 2018. https://itep.org/race-wealth-and-taxes-how-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-supercharges-the-racial-wealth-divide/.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Meg Wiehe, Aidan Davis, Carl Davis, Matt Gardner, Lisa Christensen Gee and Dylan Grundman. “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax System in all 50 States (Sixth ed.),” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, October 2018. https://itep.org/whopays/.

[5] Meg Wiehe, Jeremie Greer, David Newville and Emanuel Nieves. “Race, Wealth and Taxes: How the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Supercharges the Racial Wealth Divide,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and Prosperity Now, October 11, 2018. https://itep.org/race-wealth-and-taxes-how-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-supercharges-the-racial-wealth-divide/.

[6] Michael Leachman, Michael Mitchell, Nicholas Johnson and Erica Williams. “Advancing Racial Equity with State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15, 2018. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/advancing-racial-equity-with-state-tax-policy.

[7] Brian Lyman. “A Permanent Wound: How the Slave Tax Warped Alabama Finances,” Montgomery Advertiser, February 4, 2017. https://www.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/politics/southunionstreet/2017/02/05/permanent-wound-how-slave-tax-warped-alabama-finances/97447706/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. “Alabama: Who Pays? 6th Edition,” October 17, 2019. https://itep.org/whopays/alabama/.

[10] Michael Leachman, Michael Mitchell, Nicholas Johnson and Erica Williams. “Advancing Racial Equity with State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15, 2018. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/advancing-racial-equity-with-state-tax-policy.

[11] Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Chuck Collins, Josh Hoxie and Emanuel Nieves. “The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Divide is Hollowing Out America’s Middles Class,” Prosperity Now, September 2017. https://prosperitynow.org/files/PDFs/road_to_zero_wealth.pdf.

[12] Rebecca Burns. “The Infamous Practice of Contract Selling is Back in Chicago,” Chicago Reader, March 1, 2017. https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/contract-selling-redlining-housing-discrimination/Content?oid=25705647.

[13] Anju Chopra, Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, David Newville and Doug Ryan. “A Downpayment on the Divide: Steps to Ease Racial Inequality in Homeownership,” Corporation for Enterprise Development, March 2017. https://prosperitynow.org/files/resources/a_downpayment_on_the_divide_03-2017.pdf.

[14] Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Chuck Collins, Josh Hoxie and Emanuel Nieves. “The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Divide is Hollowing Out America’s Middles Class,” Prosperity Now, September 2017. https://prosperitynow.org/files/PDFs/road_to_zero_wealth.pdf.

[15] Andre Perry, David Harshbarger and Jonathan Rothwell. “The Devaluation of Assets in Black Neighborhoods: The Case of Residential Property,” The Brookings Institution, November 2018. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2018.11_Brookings-Metro_Devaluation-Assets-Black-Neighborhoods_final.pdf.

[16] Gary Orfield, Jongyeon Ee, Erica Frankenberg and John Kuscera. “Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future,” The Civil Rights Project, May 15, 2014. https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-60-great-progress-a-long-retreat-and-an-uncertain-future/Brown-at-60-051814.pdf.

[17] NAACP. “Fair Chance Hiring Fact Sheet,” accessed January 29, 2019. https://www.naacp.org/fairchancehiring/