The Pitfalls of Flat Income Taxes

briefWhile most states have a graduated rate income tax, some state lawmakers have recently become enamored with the idea of moving toward flat rate taxes instead. What’s the difference? And are states well served by the transition?

In short: A flat tax is one where each taxpayer pays the same percentage of their income whereas a graduated tax applies higher rates to higher incomes. Flat taxes have some surface appeal but come with significant disadvantages. Critically, a flat tax guarantees that wealthy families’ total state and local tax bill will be a lower share of their income than that paid by families of more modest means.

The Landscape

Most taxes levied by state and local governments are regressive, meaning that they charge higher rates, relative to income, for low- and middle-income taxpayers than for wealthy families. Income taxes offer an important counterbalance as they tend to be progressive, which means that they ask more of families with a greater ability to pay.

Much of the progressivity in federal and state income tax law comes from graduated rate structures. Under a graduated tax, different portions of one’s income can be taxed at different rates, with high-income families seeing more of their income taxed at higher rates than other families. Under the tax bracket structure approved by Massachusetts voters in 2022, for example, most families pay a marginal income tax rate of 5 percent while wealthy families pay that 5 percent rate on their first million dollars of taxable income and see anything over a million dollars taxed at 9 percent instead.

A desire to transition away from this system and toward one more favorable to the wealthy has long had proponents—most prominently Steve Forbes during his third-party presidential runs in the 1990s. But the idea has not taken off federally. Our graduated rate structure has persisted under the leadership of both parties, suggesting that most lawmakers are in step with the American public in preferring a graduated income tax where families with high incomes pay more.[1] And graduated rate taxes remain the norm at the state level as well.

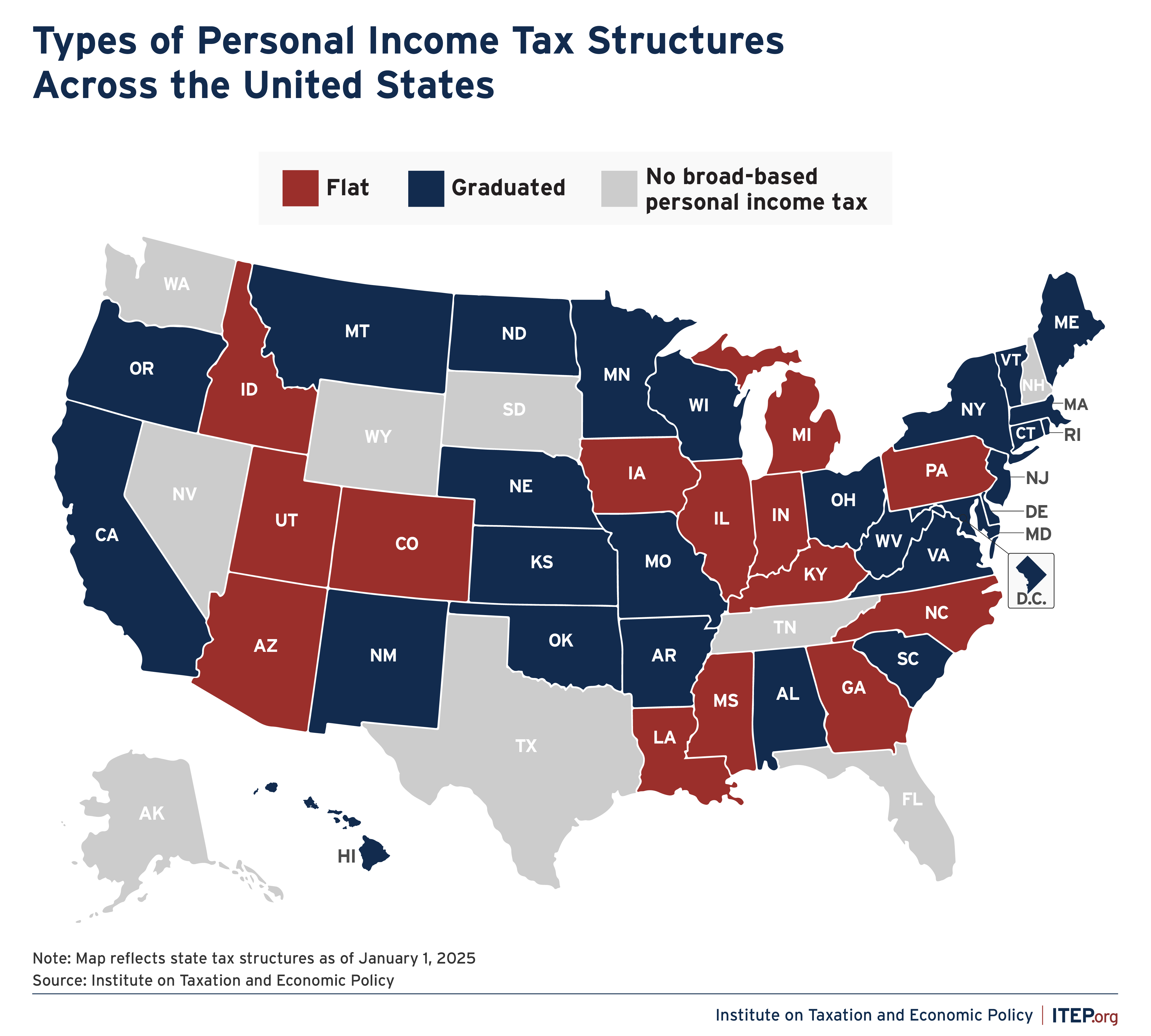

In 14 states, however, lawmakers have chosen to levy flat rate personal income tax structures. Four of these flat rate structures (Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, and Pennsylvania) are enshrined in the state constitution and are therefore difficult to reverse.

But although flat rate income taxes have received a flurry of interest in some states, graduated rate taxes remain far more common. Almost two-thirds of states with broad-based personal income tax structures have a graduated rate. Massachusetts is the most recent state to adopt a graduated rate tax after voters approved the November 2022 ballot measure which created a higher bracket on income over $1 million.

FIGURE 1

Flat Rate Income Taxes Come with Significant Downsides

Flat taxes consign states to regressive and inequitable taxation that falls far short of the “flat tax” ideal proponents claim to value, and do not advance the economic, budgetary, or simplicity goals commonly used to advocate for their enactment.

Flat income taxes guarantee a regressive overall tax system that asks more of ordinary families.

States and localities raise most of their revenue through a mix of sales, excise, property, and income taxes. Among those levies, the income tax stands out as the only major tax that is structurally progressive.[2]

Property taxes on homeowners, rental property, and motor vehicles tend to affect low- and middle-income families most as a larger share of their net worth and income is tied up in these assets. Similarly, sales and excise taxes on the purchases that families make every day also affect low- and middle-income families most because they must spend most or all of what they earn to make ends meet, whereas high-income families have the luxury of spending only a small portion of their income each year. These regressive levies tend to worsen economic and racial inequality by taxing low-income people, a disproportionate share of whom are people of color, at higher rates than other families.[3]

This means that for states to meet even the barest standard of tax fairness—an overall state tax rate that asks at least as much from the wealthy as from others —they must have a progressive income tax that counteracts the regressive effects of other taxes.

Put another way, achieving flat taxation overall—where each income group pays a similar share of their income in taxes—requires having a graduated rate income tax. Ironically, flat income taxes run counter to the goal of a flat, or “proportional,” tax system more broadly.[4]

Flat taxes are not better for the economy or small businesses.

The most common argument cited to support flat income taxes and other measures that lower taxes for affluent families is that doing so will strengthen small businesses and accelerate economic growth within a state’s borders. Neither of these claims has merit.

Small businesses tend to be organized as sole proprietorships, partnerships, or S corporations and their owners pay tax through the personal income tax code rather than through the corporate income tax. But flat taxes tend to favor those with the highest incomes—including the largest and most profitable businesses rather than the smallest.

Unlike sales or property taxes, personal income taxes are only paid on net business profits and struggling businesses that are failing to turn a profit do not owe personal income tax regardless of whether the rate is flat or graduated. Moreover, under a graduated rate system the owners of small businesses generating only modest profits will tend to be in lower tax brackets than their larger and more profitable competitors. Very large companies like Koch Industries, Publix Supermarkets, Fidelity Investments, and countless law firms, lobbying shops, and real estate firms are organized as S corporations or partnerships and see their profits taxed under the personal income tax code. A well-designed graduated rate tax can tax partners and shareholders at more profitable firms at a higher rate than mom and pop shops.

Some flat tax proponents also make sweeping claims that cutting tax bills for the owners of profitable businesses through flattening the income tax will spark faster economic growth. But the ability of state lawmakers to affect business decisions through rewriting the personal income tax code is sharply limited by the small overall size of these taxes. ITEP has calculated that state and local taxes account for just 2.3 percent of the cost of doing business, with the other 98 percent tied up in other areas like payroll, equipment, and real estate costs.[5] Moreover, according to the accounting firm Ernst & Young LLP, state personal income taxes make up just six percent of the total state and local tax bill falling on business.[6] The personal income tax is a small fraction of a small fraction of the expenses paid by business owners, suggesting that even dramatic changes in this area will have minimal impact on businesses’ bottom lines.

Finally, some defenders of flat taxes argue that repealing top brackets can prevent high-income people from leaving a state. The best research to date in this field, however, has shown that income tax levels have little impact on where the wealthiest taxpayers choose to live and that, in fact, the millionaires who stand to gain the biggest tax cut from the switch to a flat tax are already less inclined to move across state borders than other families.[7]

Flat personal income taxes are not meaningfully simpler.

Flat taxes are often advertised as being much simpler than graduated taxes because fewer rates are involved. But complexity in the income tax law is driven primarily by the tax base—particularly special carveouts from that base—rather than in the rates that are applied.

Income tax subsidies for specific activities—like donating to charity, paying mortgage interest, or collecting certain types of business or investment income—require additional documentation and a careful reading of eligibility rules that would not be required in the absence of those provisions.

Calculating the amount of tax owed under a graduated rate structure, on the other hand, is typically done automatically by one’s software or tax accountant at no extra cost in time or money relative to tax preparation under a flat tax structure. For the relatively small number of taxpayers who choose to complete their forms by hand without the aid of software, the amount of tax owed can usually be found in a table toward the end of the income tax instruction booklet. Even when that isn’t the case, only a trivial amount of additional arithmetic is required. Requiring some families to type a few extra numbers into their calculators before filing their tax forms is not a legitimate rationale for abandoning far more equitable graduated rate tax structures.

Flat rate personal income taxes often lead to higher taxes on families with modest incomes.

Contrary to the claims of some flat tax proponents, flat taxes do not lead to lower taxes across the board. Flat taxes usually bring lower tax bills for high-income households and, because of that, they produce less revenue than graduated taxes during times of rising inequality. For most families, however, there is nothing inherently “low tax” about flat taxes. In fact, flat taxes often actually result in higher overall taxes than other tax structures.

ITEP’s most recent comprehensive study of state and local tax codes found that the working class individuals and families in states with flat rate taxes paid on average 1.6 percent of what they earn in income taxes. In states with graduated-rate taxes, by contrast, that figure is just 1.3 percent.[8]

FIGURE 2

Graduated rate taxes allow states to collect more of the revenue they need to fund public services from high-income taxpayers, thereby allowing lower income tax bills for low- and middle-income families. Put another way, for a state trying to raise any given amount of revenue, a graduated rate structure will typically produce lower tax bills for most families than a flat tax, simply because the graduated rate tax is able to raise more from a relatively smaller group of very affluent families instead of from low- and middle-income earners.

In the short run, states transitioning to flat taxes have tended to obscure or delay this outcome by designing their new flat taxes as significant overall revenue losers. In Arizona, for instance, most taxpayers received an immediate income tax cut when the state adopted a flat tax structure. But while the average family in the top 1 percent received almost $16,000 in tax cuts annually under the new structure, a typical middle-income earner received just $58.[9] Looking ahead, any sales, excise, or income tax increases that Arizona might enact to compensate for dramatically declining tax contributions from the rich could very easily end up costing low- and middle-income earners far more than the tax cuts they received from the state’s new flat tax.

When flat tax proponents claim taxes will be lower, families and policymakers should ask: Lower for whom?

Flat taxes are not better for budgeting purposes.

Flat taxes are sometimes described as more stable and predictable sources of revenue for states. In large part, this is because by refusing to levy higher rates on top earners, flat taxes are blind to the soaring levels of inequality seen in recent decades and the immense fortunes being generated by the wealth of families at the very top of the income scale.

States with a progressive income tax will enjoy faster personal income tax growth during periods of dramatic expansion and rising profits for large companies and top earners. In flat tax states, by contrast, soaring fortunes at the top face the same marginal tax rate as wages and salaries being earned by middle- and low-income families.

Over the long run, states with graduated rates and sound budgeting practices will find themselves on a stronger fiscal footing than flat tax states that were not able to capture a more significant share of the windfall flowing to wealthy families.

In this light, the so-called stability and budgetary advantage offered by flat taxes is a mirage. Over the long run, states with graduated rates and sound budgeting practices will find themselves on a stronger fiscal footing than flat tax states that were not able to capture a more significant share of the windfall flowing to wealthy families.[10]

All states must carefully plan for recessions and build adequate reserves, even if they have a flat tax. Sound budgeting practices like robust Rainy Day Funds and careful projections of revenues and expenditures are what determine the health of state budgets—not the number of tax brackets included in personal income tax law.

Flat Taxes Fall Short

Despite a recent flurry of interest in flat taxes at the state level, graduated taxes—where tax rates rise with income—remain the norm at both the federal and state levels. This is for good reason, as flat rate structures come with significant downsides and their advantages are mostly illusory.

Flat taxes leave states ill-equipped to deal with the regressive effects of their other taxes, consigning states to a fate of having to tax high-income families more lightly than low- and middle-income families. So paradoxically, flat income taxes move states further away from the “flat tax” ideal that proponents claim to value, as the overall distribution of taxes tends to be steeply regressive—not flat—in states choosing to levy flat taxes.

On top of that, each of the most common claims made in support of flat taxes—that they will promote economic growth, strengthen small business, improve state budgeting, simplify the tax system, or lower taxes for a broad swath of families—are without merit.

Ultimately, flat taxes are out of step with public concern about inequality and enacting one all but abandons even the possibility of an equitable tax system.

Endnotes

[1] Frank Newport, “Americans’ Long-Standing Interest in Taxing the Rich,” Gallup, February 2019.

[2] Davis, Carl, et al. “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States, 7th ed.,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2024.

[3] Carl Davis, Misha Hill, and Meg Wiehe, “Taxes and Racial Equity: An Overview of State and Local Policy Impacts,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. March 2021.

[4] See Figure 12 of “Fairness Matters: A Chart Book on Who Pays State and Local Taxes,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, April 2024.

[5] Carl Davis and Matthew Gardner, “Tax Foundation’s ‘State Business Tax Climate Index’ Bears Little Connection to Business Reality,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, October 2022.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Carl Davis, “New Research Shows Millionaires Less Mobile than the Rest of Us,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, May 2016.

[8] Result is for the second quintile of earners, or those with incomes between $23,500 and $45,900 per year. See Figure 7 of “Fairness Matters: A Chart Book on Who Pays State and Local Taxes,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, April 2024.

[9] “$2 Billion Tax Cuts for the Rich are Irresponsible,” Arizona Center for Economic Progress, May 2022.

[10] Matt Gardner, “In It for the Long Haul: Why Concerns over Personal Income Tax ‘Volatility’ Are Overblown,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, March 2011.