Read the Repatriation Fact Sheet.

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. tax code allows multinational corporations to indefinitely defer taxes on their foreign subsidiaries’ earnings as long as those profits remain officially abroad. But once corporations repatriate these funds (transfer subsidiary profits to their U.S. parent company), they are subject to federal taxes. This provision has created a gaping loophole that incentivizes corporations to “permanently reinvest” funds in low-tax jurisdictions to indefinitely defer paying U.S. taxes. It has led to accounting tricks through which corporations claim wildly inflated earnings in tax haven countries (such as the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Bermuda, and the Cayman Islands), in some instances reporting profits that far outstrip small tax haven nations’ entire GDP.[1]

Corporations falsely claim that they have to engage in offshore tax avoidance maneuvers because the U.S. corporate tax rate is too high, an argument which has unfortunately found an audience in lawmakers on both sides of the aisle. In 2017, Congress likely will evaluate a number of approaches to taxing the trillions of dollars corporations currently hold offshore. This report explains and evaluates these proposals, including a so-called repatriation holiday and deemed repatriation. Further, it explains why ending deferral of taxes on U.S. multinational corporations’ foreign earnings could halt the widespread corporate practice of funneling money to subsidiaries for the express purpose of avoiding taxes.

Deferral and the Taxation of Foreign Profits

U.S. multinational corporations hold almost $2.5 trillion in offshore permanently reinvested earnings as of 2015.[2] Why is such a huge sum held abroad and designated as “permanently reinvested”? The answer has to do with the way the U.S. corporate income tax system treats multinational corporations’ foreign subsidiary earnings. In a residential (or worldwide) tax system, corporations are taxed on all their income, regardless of where they earned it. At the other end of the spectrum is a territorial tax system, in which corporate income taxes are only collected on income earned within the country. The U.S., like many other nations, has a hybrid of these two systems. Corporate income earned in the United States is subject to the full 35 percent statutory federal corporate tax rate. However, corporations can defer paying taxes on foreign income until they “repatriate” foreign profits (i.e., paid to the U.S. parent company as dividends). Additionally, the U.S. tax system provides a foreign tax credit on repatriated income, which is a dollar-for-dollar reduction in U.S. tax liability to offset any taxes paid to foreign governments (limited to the total U.S. tax that would be due in cases where the foreign tax rate is higher than the U.S. rate).

This deferral system creates a tax incentive for multinational corporations to increase the share of earnings they book abroad (at least on paper). While corporations may legitimately earn some profits via foreign subsidiaries, this system encourages companies to disguise U.S.-earned profits as foreign for the sole purpose of avoiding U.S. taxes. Further, corporations hold a large portion of profits in tax havens, so many pay little to nothing in foreign taxes. The latest IRS data show that 59 percent of multinationals’ reported foreign earnings in 2012 were allegedly earned in 10 jurisdictions widely considered to be tax havens.[3] A recent report, titled Offshore Shell Games, found that 367 Fortune 500 companies (73 percent) had at least 10,366 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens as of 2015. The report explains why a significant number of these subsidiaries likely are shell companies created for the express purpose of booking profits and avoiding taxes. Further, the report found these companies are likely avoiding up to $718 billion in U.S. taxes on their $2.5 trillion in cumulative earnings held offshore.[4]

Repatriation Tax Proposals Background

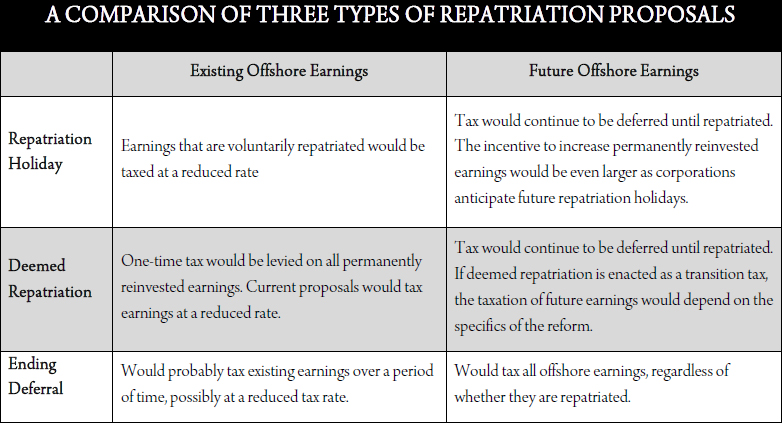

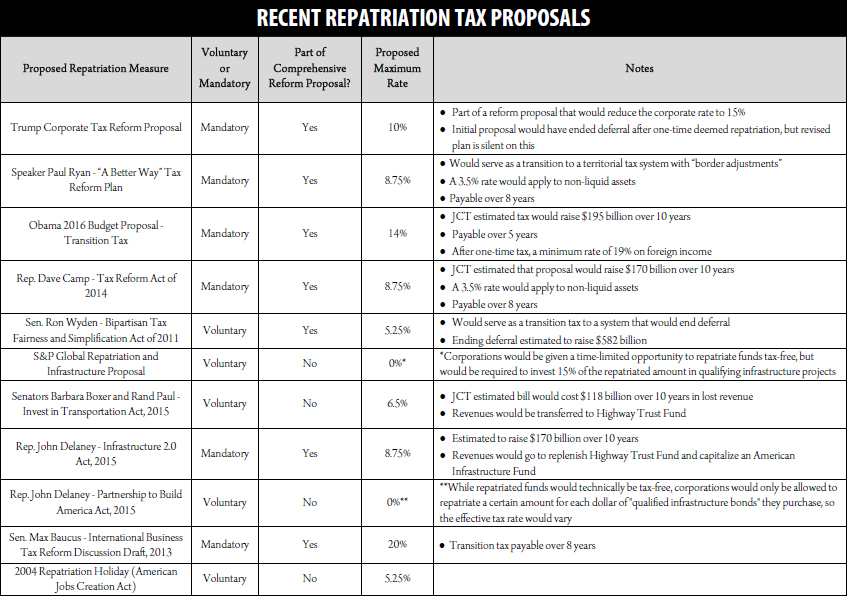

In the past several years, proposals for a “repatriation holiday” or a “deemed repatriation” have become increasingly popular among lawmakers and presidential candidates. Under a repatriation holiday, corporations can voluntarily repatriate foreign earnings for a limited time at a sharply reduced tax rate. Proponents tout proposals for a repatriation holiday as a way to encourage U.S. multinationals to bring home some of the trillions in profits that the U.S. government has not taxed. A deemed repatriation would treat all accumulated foreign earnings as repatriated, regardless of whether they are actually brought back to the United States, but it would also tax them at a lower rate than the 35 percent statutory corporate rate. While both of these proposals would lead to a short-run increase in revenue by collecting taxes on those offshore profits that are currently deferred, the reduced rates would result in decreased revenue in the longer run, in part by encouraging corporations to move even more of their earnings offshore in anticipation of another future repatriation holiday.

Under a repatriation holiday, companies are not required to repatriate their foreign profits but may do so to take advantage of a special lower tax rate. Lawmakers first conceived of repatriation holidays as tools for economic stimulus under the assumption that they would give companies an incentive to use profits that were “trapped” offshore to increase domestic investment, spurring job creation. This was the rationale for a repatriation holiday enacted in 2004 as part of the American Jobs Creation Act (P.L. 108-357), which, for a limited time, allowed corporations to repatriate their offshore earnings at a rate of 5.25 percent (in contrast to the 35 percent statutory corporate rate). Members of Congress put forth proposals for a repeat of a similar repatriation holiday during the Great Recession and subsequent recovery, but they never passed.

A related set of proposals would allow corporations to voluntarily repatriate earnings “tax-free” in exchange for an investment in qualified infrastructure projects. For instance, Rep. John Delaney put forth a bill in 2015 (Partnership to Build America Act) that would have permitted the tax-free repatriation of up to six dollars for every dollar a company purchases in bonds to capitalize a $50 billion infrastructure bank. The effective tax rate paid by companies on these earnings would be determined by the ratio of tax-free repatriation (determined by an auction) and the opportunity cost of investing in the 50-year infrastructure bonds versus other more profitable investments.[5] A more recent proposal by S&P Global would similarly allow corporations to repatriate offshore funds at a zero tax rate on the condition that they invest 15 percent of the repatriated amount in infrastructure projects.[6] In contrast to the Delaney proposal, companies would only be required to invest in short-term market rate infrastructure-related bonds and the amount that could be brought back would be unlimited. In other words, the S&P proposal would result in little if any additional infrastructure investment, while at the same time allowing companies to repatriate all of their earnings essentially tax and cost-free.

In contrast to a repatriation holiday, a deemed repatriation would require multinationals to pay a tax on their previously untaxed offshore earnings, regardless of whether they are repatriated. While a deemed repatriation could tax these earnings at the full corporate rate, all recent proposals call for a reduced rate. Most of these proposals have been part of broader corporate tax overhaul proposals, and the tax collected on accumulated offshore earnings would be considered a “transition tax” as the U.S. moves to a new tax regime. The table in the appendix details the various repatriation tax proposals that have been put forth.

Problems with a Repatriation Holiday

Effectiveness

While some proposals for repatriation holidays are defended as economic stimuli, there is no evidence that they have this effect. A report by the Congressional Research Service found that the 2004 repatriation holiday did not lead to job creation or economic growth.[7] Instead, there is evidence that corporations distributed a large portion of repatriated profits to shareholders via higher dividends or stock repurchases or used the money to increase executive pay. Although the law intended to prohibit these uses of repatriated funds, corporations could use these funds for already budgeted expenses, freeing up cash for “prohibited” uses. Some of the proposals, including the Sen. Barbara Boxer, Sen. Rand Paul and Sen. Ron Wyden bills, include similar restrictions to the earlier repatriation holiday, but the fungibility of corporations’ funds would make them impossible to enforce. Those companies that benefitted the most from the 2004 repatriation were no more likely than other corporations to use the repatriated funds for growth-generating activities.[8] In fact, many of the companies that took advantage of the repatriation holiday reduced their domestic workforces in subsequent years.[9]

Additionally, claims that repatriation holidays will free up funds that would otherwise be “trapped” offshore are contradicted by findings that much or most of these funds are already invested in the U.S. economy. A study by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations surveying 27 corporations, including the 15 that repatriated the most funds during the 2004 repatriation holiday, found that at least 46 percent of their offshore “permanently reinvested” earnings were invested in U.S. assets like Treasury bonds, U.S. stocks, and U.S. bank deposits by the American corporations’ controlled foreign subsidiaries.[10] Multinationals are theoretically prohibited from using these funds to invest in their own U.S. operations, pay shareholder dividends, or repurchase stock, but they can get around this by borrowing at low interest rates, using their foreign earnings as implied collateral.

Fiscal Issues

Another failure of repatriation holidays is that while they may increase revenue in the first few years, they result in a significant revenue loss in the long run, as profits are repatriated early, leaving less to be repatriated later, and as firms are encouraged to move even more profits abroad in anticipation of another tax holiday. Previous ITEP research (published in a report by Citizens for Tax Justice (CTJ)) found that the 20 corporations that repatriated the most offshore profits under the 2004 holiday nearly tripled the amount of cash “permanently reinvested” offshore between 2005 and 2010, indicating that corporations are indeed hoping for another repatriation holiday to take advantage of the lower rates.[11] The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that the Boxer/Paul proposal, which is similar to the 2004 repatriation holiday but with a rate of 6.5 percent, would have cost $118 billion in revenue over 10 years.[12] Thus, proposals that would use revenues from repatriation to fund infrastructure improvements (see, for instance, the bills proposed by Rep. John Delaney and by Sens. Boxer and Paul) are simply gimmicks that raise money in the very short run but lose much more revenue thereafter.

Fairness Issues

Another problem with repatriation holidays is that they reward corporations for aggressive tax avoidance. Corporations that have shifted profits into offshore tax havens have more to gain from repatriation holidays since they have paid little or no foreign taxes to offset their U.S. tax liability. These companies can also more easily move funds into tax havens compared to companies whose foreign investments are in things like buildings and equipment. One study found that the companies that repatriated under the 2004 holiday were, on average, larger and had lower effective foreign tax rates than those that did not repatriate, suggesting that the repatriating companies use foreign operations as tax-avoidance strategies.[13] IRS data show that three quarters of funds repatriated during the 2004 holiday had previously been held in tax haven jurisdictions.[14] Additionally, around half of the repatriations were by pharmaceutical and technological companies, who can more easily shift U.S. earnings offshore by transferring intellectual property such as patents and copyrights to their foreign subsidiaries.[15]

Problems with Deemed Repatriation

A deemed repatriation of accumulated offshore earnings can be viewed as either a tax increase or a tax cut in the context of the current international tax system, depending on whether those earnings would have ever been repatriated. Earnings that are permanently invested in operations abroad may never be repatriated, and since those earnings are not taxed under the deferral system, a deemed repatriation would result in a tax increase. However, because a significant portion of permanently reinvested earnings are not invested in operations and may eventually be repatriated at the full 35 percent rate, a deemed repatriation at a lower rate would represent a tax break on these earnings. Just as with a repatriation holiday, a low preferential rate may encourage corporations to shift more of their future earnings abroad in anticipation of another future deemed repatriation and would provide the greatest rewards to the most egregious tax dodgers. An analysis using ITEP data of President Obama’s proposal for a 14 percent transition tax identified 10 major corporations, each with at least $17 billion in “permanently reinvested” offshore profits, that would collectively owe $97 billion less in taxes than if the full 35 percent rate was applied.[16]

Another problem common to both deemed repatriation and repatriation holiday proposals is that they are short-sighted. A large portion of revenues raised is likely to simply reflect the shifting forward of revenues that would have been received from foreign income repatriated in later years. The revenue implications of a deemed repatriation will depend on what portion of permanently reinvested earnings would have later been repatriated. The JCT estimated that President Obama’s transition tax, which is payable over five years, would raise revenue in the first six years, but lose revenue in the next four years.[17]

One concern that has been raised about a deemed repatriation is that companies with investments in non-cash assets abroad (e.g. factories) may not have the liquidity to cover their U.S. tax liability. The tax reform proposal by the former Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp attempted to address this issue by setting a lower rate on non-cash assets than on cash and other more liquid assets. However, it is likely that corporations with non-cash foreign investments (as opposed to those with liquid assets held in tax havens) are already paying significant foreign taxes and would have little or no U.S. tax liability under a deemed repatriation once foreign tax credits are taken into account. In the event that corporations do face liquidity challenges, most proposals more than adequately deal with this issue by allowing the tax to be paid over several years.

Ending Deferral of Tax on Foreign Earnings is a Better Long-Term Solution

If Congress wants to increase revenues and encourage domestic investment, it needs to take away the incentive for U.S. multinationals to shift profits to tax havens in the first place. It could accomplish this by ending the policy of deferring taxes on foreign income. This would mean that corporations would pay the same rate on all income, whether it is earned at home or abroad (or earned in the U.S., but disguised as foreign earnings). Plus, the tax would be due as the income is earned, eliminating the potential for perpetual deferral. Deferral will cost an estimated $1.3 trillion in revenue over the next 10 years, so the revenue that could be raised from ending it would be substantial.[18] In the transition to a new system without deferral, the $2.5 trillion currently designated as permanently reinvested should also be taxed at the full corporate rate (adjusted for foreign tax credits) over a period of time, which could bring a one-time revenue influx of $718 billion.[19] As momentum gathers around international tax reform, ending deferral is an option that needs to be on the table. It would succeed where repatriation holidays and deemed repatriations fail.

[1] Citizens for Tax Justice, American Corporations Tell IRS the Majority of Their Offshore Profits Are in 10 Tax Havens, April 7, 2016. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/american_corporations_tell_irs_the_majority_of_their_offshore_profits_are

_in_12_tax_havens.php

[2] Citizens for Tax Justice, Offshore Shell Games 2016, October 4, 2016. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2016/10/offshore_shell_games_2016.php

[3] Citizens for Tax Justice, American Corporations Tell IRS the Majority of Their Offshore Profits Are in 10 Tax Havens, April 7, 2016. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/american_corporations_tell_irs_the_majority_of_their_offshore_profits_are

_in_12_tax_havens.php

[4] Citizens for Tax Justice, Offshore Shell Games 2016, October 4, 2016. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2016/10/offshore_shell_games_2016.php

[5] Representative John Delaney, “Information on the Partnership to Build America Act (H.R. 2084),” Accessed October 25, 2016. https://delaney.house.gov/infrastructure/information-on-congressman-delaneys-infrastructure-bill

[6] Beth Ann Bovino, Jason Gold, and Shripad Joshi, S&P Global, “Rebuilding Through Repatriation: How Corporate Cash Can Save America’s Infrastructure,” October 5, 2016. https://www.spglobal.com/Market-Insights/Rebuilding-Through-Repatriation

[7] Donald J. Marples and Jane G. Gravelle, Congressional Research Service, “Tax Cuts on Repatriation Earnings as Economic Stimulus: An Economic Analysis,” May 27, 2011. http://www.ctj.org/pdf/crs_repatriationholiday.pdf

[8] Roy Clemons and Michael R. Kinney, “An Analysis of the Tax Holiday for Repatriation Under the Jobs Act,” Tax Analysts Special Report, October 20, 2008. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2339752

[9] Donald J. Marples and Jane G. Gravelle, Congressional Research Service, “Tax Cuts on Repatriation Earnings as Economic Stimulus: An Economic Analysis,” May 27, 2011. http://www.ctj.org/pdf/crs_repatriationholiday.pdf

[10] United States Senate, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, “Offshore Funds Located Onshore: Majority Staff Report Addendum,” December 14, 2011. http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/download/report-addendum_-psi-majority-staff-report-offshore-funds-located-onshore

[11] Citizens for Tax Justice, Data on Top 20 Corporations Using Repatriation Amnesty Calls into Question Claims of New Democrat Network, August 26, 2011. http://www.taxjusticeblog.org/archive/2011/08/data_on_top_20_corporations_us.php

[12] Richard Rubin, “Repatriation Tax Break from Boxer, Paul Cost $118 Billion,” Bloomberg Business, April 30, 2015. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-04-30/repatriation-tax-break-from-paul-boxer-would-cost-118-billion

[13] Roy Clemons and Michael R. Kinney, “An Analysis of the Tax Holiday for Repatriation Under the Jobs Act,” Tax Analysts Special Report, October 20, 2008. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2339752

[14] Americans for Tax Fairness, ”Repatriated Dividends from 12 Tax Havens Due to the 2004 Tax Holiday Legislation, 2004 — 2006.” http://www.americansfortaxfairness.org/files/Repatriated-Funds-from-Tax-Havens-2004-2006.pdf

[15] Chuck Marr and Chye-Ching Huang, Repatriation Tax Holiday Would Lose Revenue And Is a Proven Policy Failure, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 20, 2014. http://www.cbpp.org/research/repatriation-tax-holiday-would-lose-revenue-and-is-a-proven-policy-failure?fa=view&id=4154

[16] Citizens for Tax Justice, Corporations Would Save $97 Billion in Taxes Under “Transition Tax” on Offshore Profits, February 16, 2016. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2016/02/ten_corporations_would_save_97_billion_in_taxes_under_transition_tax_on

_offshore_profits.php

[17] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2017 Budget Proposal,” March 24, 2016. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4902

[18] Americans for Tax Fairness and Economic Policy Institute, “Corporate tax chartbook,” September 19, 2016. http://www.epi.org/publication/corporate-tax-chartbook-how-corporations-rig-the-rules-to-dodge-the-taxes-they-owe/

[19] Citizens for Tax Justice, Offshore Shell Games 2016, October 4, 2016. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2016/10/offshore_shell_games_2016.php