Download National and State-by-State Data on “Compromises” for Tax Bill

One of the most surprising aspects of the current tax debate is that Republican leaders in Congress, who for years have railed against tax increases, are now advancing a bill that would raise taxes on millions of families even while it reduces taxes overall, especially for corporations, and increases the budget deficit. Most taxpayers would initially pay less than they do today under both the House and Senate bills, but some would pay more right away and many more would face tax increases throughout the decade.

Tax increases under the proposals would be most common for those who currently pay higher state and local taxes, which can be deducted on the federal tax return today. The tax legislation making its way through Congress would eliminate most of this deduction by limiting it to a maximum $10,000 deduction for property taxes. State and local income taxes would not be deductible at all.

Republicans in Congress reportedly are considering two versions of a change they claim would “improve” the current bills by making them more generous to residents of higher-taxed states. As illustrated by the numbers below, the reality is that these proposals would make little difference on those states and taxpayers hit hardest.

One “compromise” being discussed would allow taxpayers to deduct both state and local income taxes and property taxes, but the combined amount deducted would be capped at $10,000.

Another possible version of the compromise would be even less generous and have even less impact on the households hurt by the Senate tax bill. Under this scenario, taxpayers would be forced to choose deducting either state and local income taxes or deducting property taxes, and they could only deduct up to $10,000 of whichever they choose. This is less generous than the previous compromise described because some taxpayers might have both income taxes and property taxes to deduct but have less than $10,000 of either. For example, if a taxpayer paid $6,000 in state income taxes and $4,000 in property taxes, under this less generous compromise, the taxpayer would deduct the larger of the two (the $6,000 in state income taxes) but would not be able to deduct the combined amount of $10,000.

While these changes would add significant costs to the bill — almost $9 billion or $6 billion in the first year — it would have no significant impact for taxpayers hurt by the current bill and nearly no impact for low- and middle-income households.

Nationally, the total tax cuts and average tax cut in 2019 would be just 3 percent or 2 percent greater than under the Senate bill as passed. For the bottom three-fifths of taxpayers (the lowest-income 60 percent of taxpayers) this “compromise” would increase the average tax cut by just $2 to $5. Whereas the Senate bill as passed would raise taxes on about 9 percent of taxpayers, this compromise would drop that share to 7 percent or 8 percent of taxpayers.

Including one of these compromises in the final bill be would provide little comfort to the 7 to 8 percent of taxpayers who would still face a tax increase while most high-income households and corporations pay less.

Even in California, which has higher state and local taxes and where lawmakers are particularly concerned about this issue, the two possible compromises would increase total tax cuts going to the state and the average tax cut for state residents by only 7 percent or 5 percent. The share of California taxpayers facing a tax hike would drop slightly from 14 percent under the Senate bill as passed to 11 percent or 12 percent.

This finding is unsurprising because the average state and local tax deduction (including deductions for income taxes, property taxes and other state and local taxes) claimed by Californians who itemize will be more than $23,000 under current law. The average deduction for state and local income taxes is about $21,000 and the average property tax deduction just under $7,000. This helps to explain why even a compromise that allows both deductions within the $10,000 cap fails to help many California taxpayers.

California lawmakers can hardly call this compromise a victory when the end result would be a bill that raises taxes on more than a tenth of the state’s residents in order to cut taxes dramatically on corporations. As explained in another ITEP blog post, California is one of the states that pays a large share of federal personal income taxes relative to its population. This tax plan would increase the share paid by California even if either of the compromises described here is included.

Another higher-taxed state is New York. As illustrated in the table below, these two possible compromises make even less of a difference there. They would increase the total tax cuts going to New York and the average tax cuts for the state’s residents in 2019 by just 5 percent or 4 percent. The share of New York taxpayers facing a tax hike in 2019 would drop slightly from 15 percent under the Senate bill as passed to 14 percent under either version of the compromise.

The average state and local tax deduction for those who itemize currently in New York is more than $26,000 and like California, the income tax deduction is much more valuable than the property tax deduction.

Like California, New York is one of the states that pays a large share of federal personal income taxes relative to its population. As explained in another ITEP blog post, this tax plan would increase the share paid by the state’s residents even if either of the compromises described here is included.

More Tax Increases After 2025 in Every Version of the Senate Tax Bill

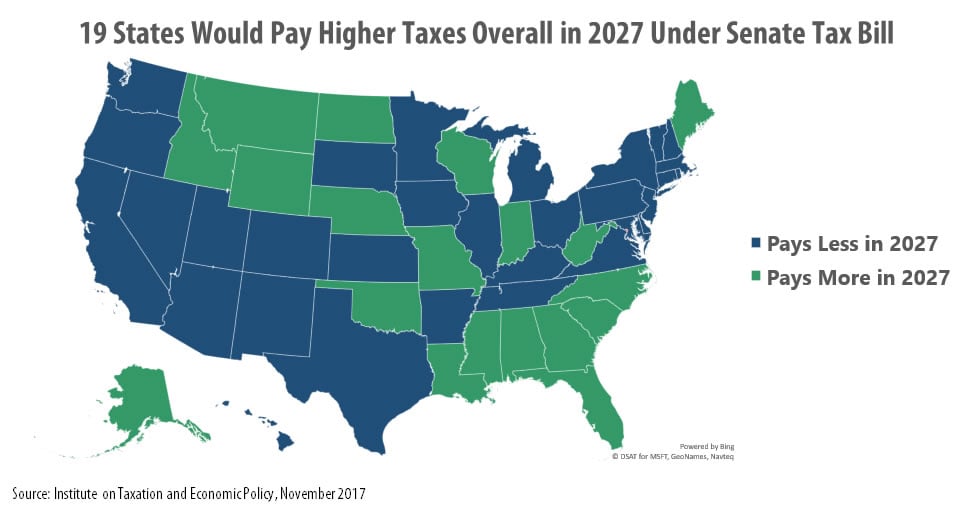

The share of taxpayers facing higher taxes would increase dramatically after 2025 in any of these scenarios. Under the Senate tax bill, all the provisions affecting families and individuals would expire after 2025, with the exception of a change to the inflation adjustments in the tax code (chained CPI), which would raise taxes on all income groups. Families can therefore expect a tax increase in later years unless the believe they will benefit from the corporate tax cuts and estate tax cuts, which are permanent under the Senate bill. As a result, the residents of 19 states would pay more in total federal taxes in 2027 than they pay today.

Republicans claim this is not a problem because all the provisions of the bill would eventually be made permanent. But it’s worth noting that corporate CEO’s did not trust such promises and demanded that their tax cuts be made permanent, and that’s exactly what Republicans leaders provided in this legislation.

Why Do these Compromises Accomplish So Little?

There are many reasons why some households would face tax hikes right away under this legislation, and several of those reasons are not addressed by the “compromises” that are being discussed.

Many people whose deductions are limited would nonetheless pay less because the tax plan increases the standard deduction, which they can claim instead of itemized deductions. (The deduction for state and local taxes in one of several itemized deductions). But those with total itemized deductions that are greater than the increased standard deduction might not be so lucky.

Take the example of a married couple who claims $28,000 in itemized deductions under current law. This includes $11,000 in state and local income taxes, $5,000 in property taxes, and additional deductions for home mortgage interest and charitable giving. Under the Senate bill as passed, the amount of itemized deductions that this couple could claim would drop from $28,000 to $17,000 (because the $11,000 in state income taxes would no longer be deductible).

The House and Senate tax bills would allow a standard deduction of $24,400 for married couples in 2019. This couple would claim the standard deduction because this is greater than the amount of itemized deductions they would be allowed. In other words, this couple stops itemizing and benefits from the increase in the standard deduction, but is allowed to deduct less under the bill ($24,400) than they would under current law ($28,000).

On top of that, the House and Senate tax bill would repeal personal exemptions. Under current law, the combination of personal exemptions plus the standard deduction (or itemized deductions for those who itemize) determines the amount of income that is shielded from income tax. Under current law, in 2019 this couple would have two personal exemptions equal to $4,250. Their personal exemptions combined with their $28,000 in itemized deductions allow them to shield $36,500 from federal income tax. Under the House and Senate bills, they would be able to shield just $24,400 from federal income taxes (because the standard deduction would be $24,400).

Because this couple does not have children, they would not benefit from the increased child tax credits in both bills. As a result, this couple could pay more overall, depending on their circumstances and how they are affected by other aspects of the tax plan.

The first compromise discussed here would not help this couple. Under the Senate bill as passed they could only claim $17,000 in itemized deductions, which includes $5,000 in property taxes. Under the first possible compromise, they could also deduct $5,000 of their state and local income taxes (for a total of $10,000 in combined deductions for income taxes and property taxes). This would increase the total amount of itemized deductions they could claim to $22,000.

It would still make more sense for them to claim the standard deduction, which would be $24,400 under the legislation in 2019. The total amount of income they could shield from federal income taxes would therefore not change. The second compromise discussed here would accomplish even less than the first.

The couple in this example are likely to be relatively well-off but other taxpayers who could face a tax increase are not. Some do not itemize under current law and therefore would not benefit at all from any compromise related to itemized deductions. For example, some taxpayers who have dependents who are not children (and therefore not eligible for the increased child tax credit under the House and Senate tax bills) would face higher taxes. They would lose the exemption they can claim for each dependent but would not benefit from the increased child tax credit. Anyone with adult children living with them or children in college, or elderly parents living with them as their dependents, could be in this situation.

EITC recipients would see their EITC benefit reduced in 2019 because of the slower inflation adjustment (chained CPI) that would gradually make many deductions and credits less generous over time. This effect would be slight in the first year, but over time the reduction in the EITC and other tax benefits would become more apparent.

The compromises discussed here to modify the tax plan would not help these groups.