Overview

Policymakers have options when constructing state and local tax codes. Choosing graduated-rate income taxes collects more revenue from higher-income households who can most afford to pay. Avoiding top-heavy exemptions and deductions ensures that the wealthiest actually pay that fairer share. Reducing the share of revenue from sales taxes can increase fairness, as can making sure that sales taxes reflect the modern economy. And having robust, progressive income taxes instead of overly relying on sales taxes often generates much more adequate revenue for the services that make communities and families thrive.

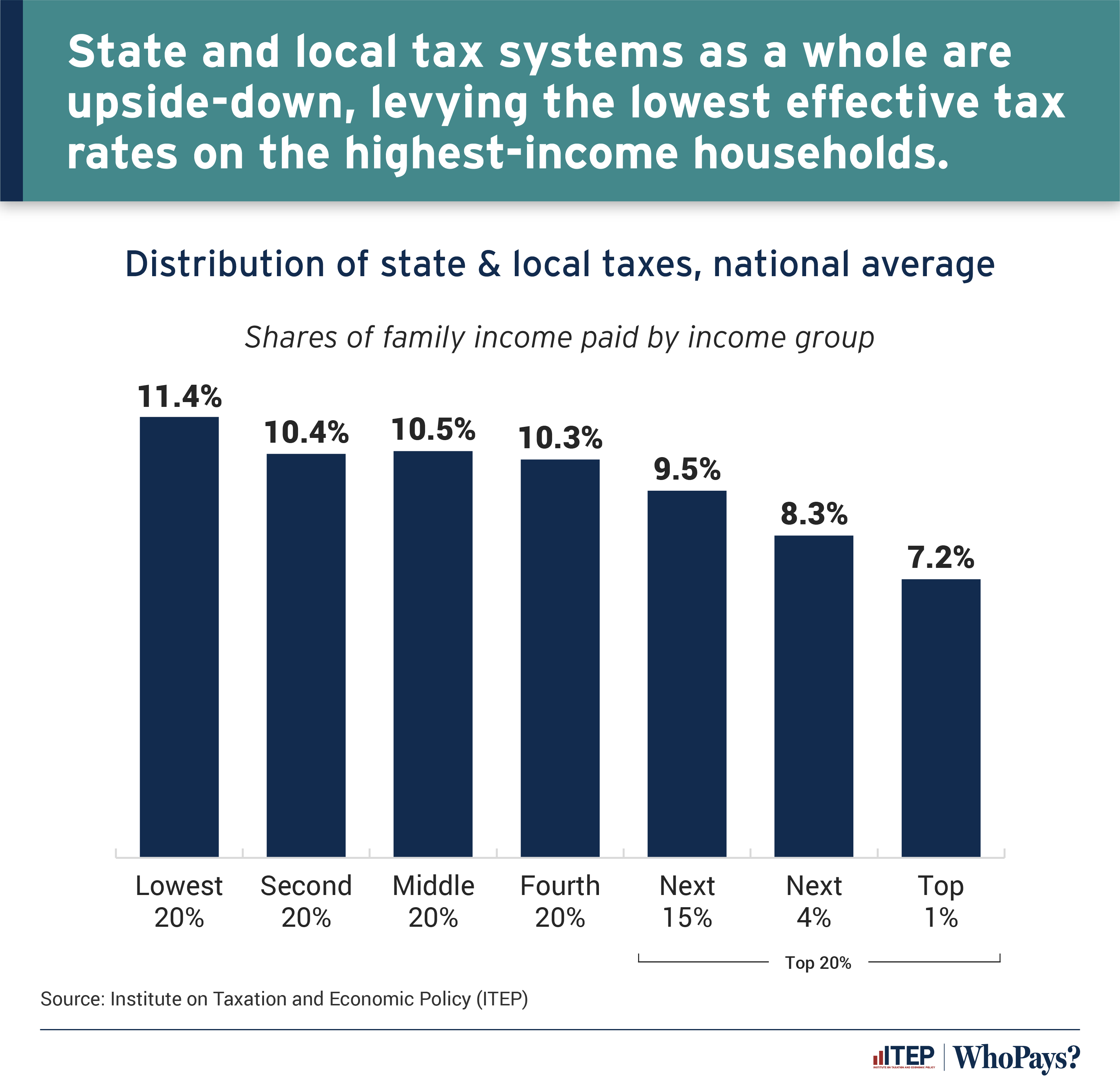

Too often, however, would-be tax reformers propose policies that would worsen one of the most undesirable features of state and local tax systems: their lopsided impact on taxpayers at varying income levels. Nationwide, the bottom 20 percent of earners pay 11.4 percent of their income in state and local taxes each year. Middle-income families pay a slightly lower 10.5 percent average rate. But the top 1 percent of earners pay just 7.2 percent of their income in such taxes. This is the definition of a regressive, upside-down tax system.

State and local tax codes can do a lot to reduce inequality. But they add to the nation’s growing income inequality problem when they capture a greater share of income from low- or moderate-income taxpayers. These regressive tax codes also result in higher tax rates on communities of color, further worsening racial income and wealth divides.

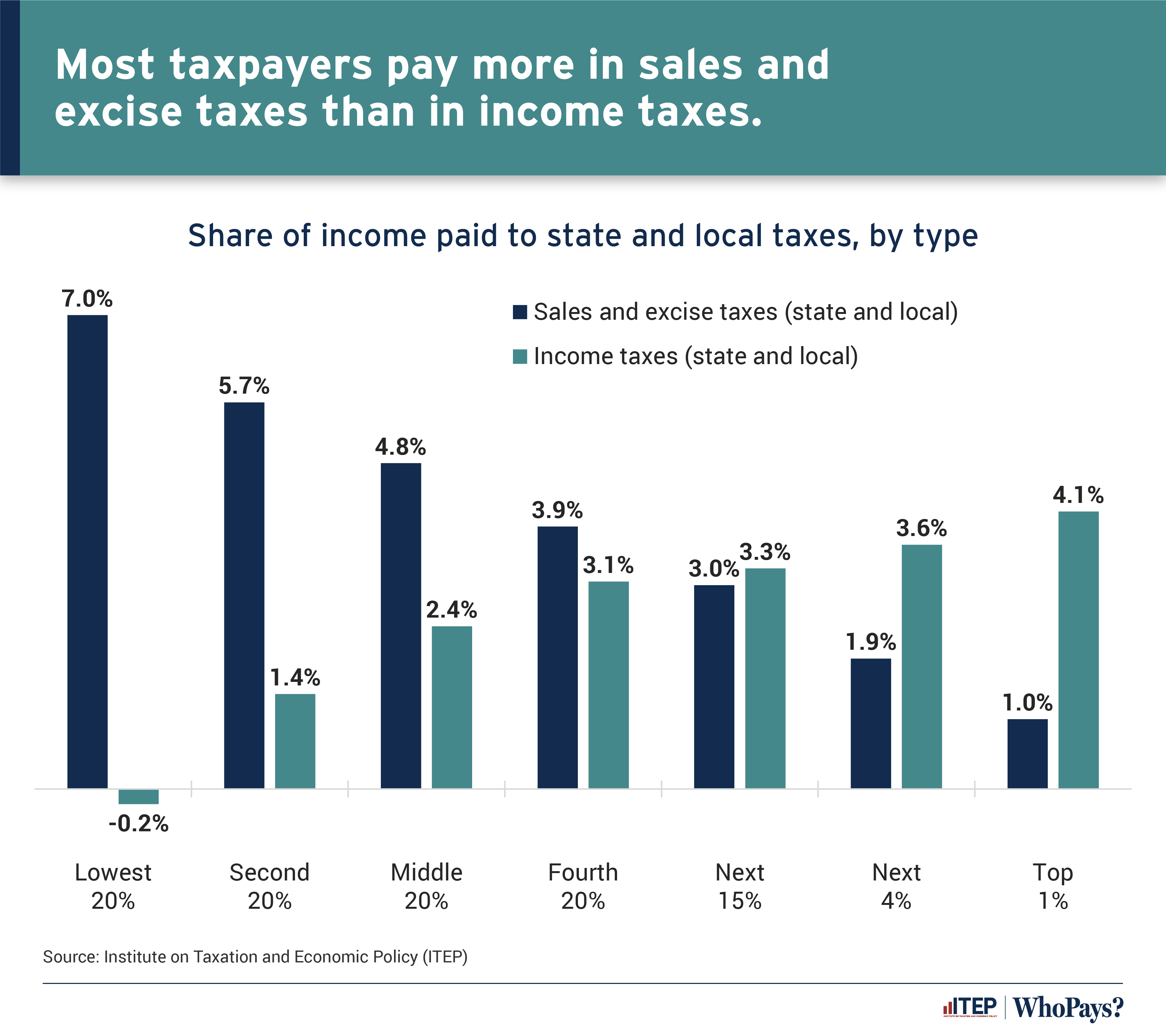

Heavy reliance on sales and excise taxes is a key driver of this regressivity. Middle- and low-income taxpayers typically pay more tax on what they buy (sales and excise taxes) than on what they earn (income taxes), though many families may not notice since sales taxes are spread out over countless purchases made throughout the year.

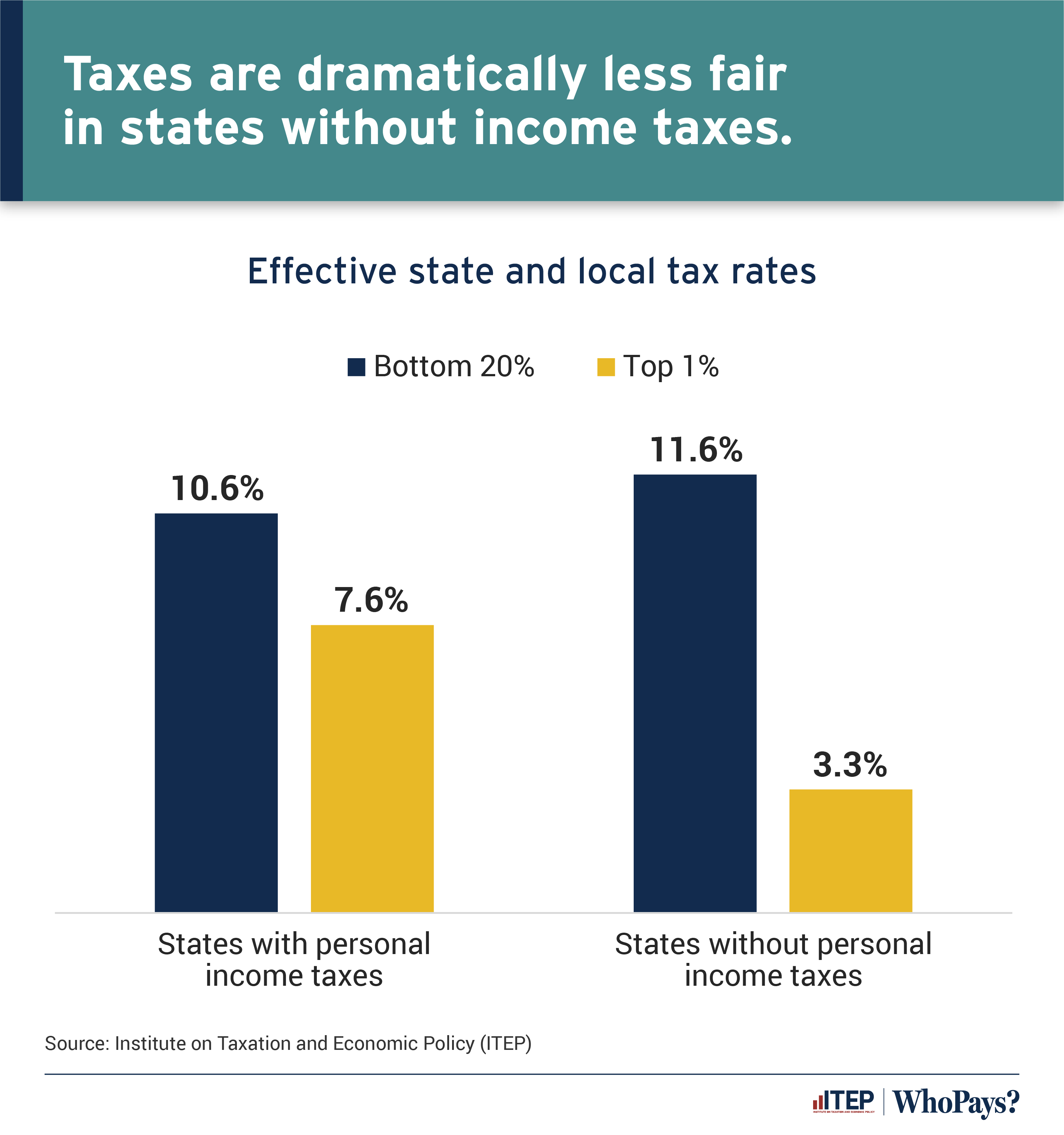

When states reduce or reject personal income taxes in favor of higher sales and excise taxes, high-income taxpayers benefit at the expense of low- and moderate-income families who often face above-average tax rates to pick up the slack.

State tax systems that ask the most of families with the least are also less able to generate the revenue needed to fund schools, health care, infrastructure, and other public services that are crucial to building thriving communities. This problem is particularly acute over the long run since regressive tax systems depend more heavily on low-income families who face stagnating incomes while asking less of high-income earners, whose wealth and incomes continue to grow.

It does not have to be this way. States vary considerably in the fairness of their tax codes. Lawmakers can reduce inequity by pursuing more progressive tax policies that have proven successful in many states already.

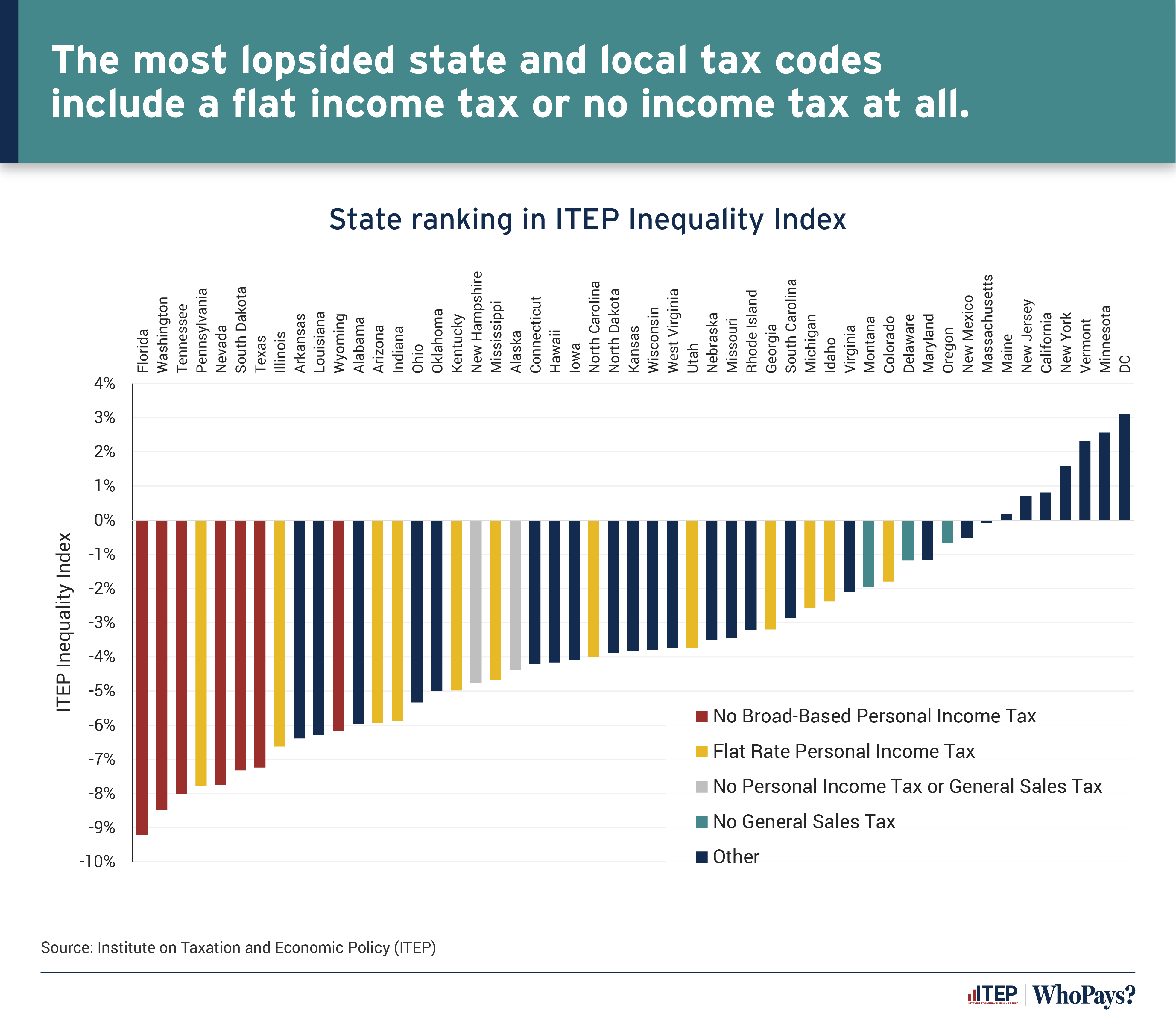

States levying robust personal income taxes with graduated tax rates and targeted refundable credits, for example, tend to have overall tax systems that are more reflective of taxpayers’ ability to pay. By contrast, states with flat-rate personal income taxes or no personal income tax at all have among the most regressive tax systems in the nation.

Given the detrimental impact that regressive tax policies have on economic opportunity, income inequality, racial wealth disparities, and long-run revenue sustainability, tax reform proponents should employ proven progressive tax options.

(Click on each chart to expand)

Virtually every state tax system is fundamentally unfair, taking a greater share of income from low- and middle-income families than from high-income families. On average, the poorest 20 percent of taxpayers spend 11.4 percent of their income on state and local taxes, which is nearly 60 percent higher than the 7.2 percent average effective rate for the top 1 percent.

While the reasons for this disparity vary by state, overreliance on regressive consumption taxes and the lack of a sufficient personal income tax are two of the most common drivers within state and local tax codes. By raising income taxes, particularly on higher-income households, states can generate revenue from those most able to pay that can then be used to fund crucial services, provide targeted tax credits, or reduce regressive sales taxes.

Note: These figures are a weighted national average of total state and local tax payments over total income, grouped according to each state’s distribution of income. As with the rest of the data underlying this chart book, these figures come from the seventh edition of ITEP’s Who Pays? report, published January 2024.

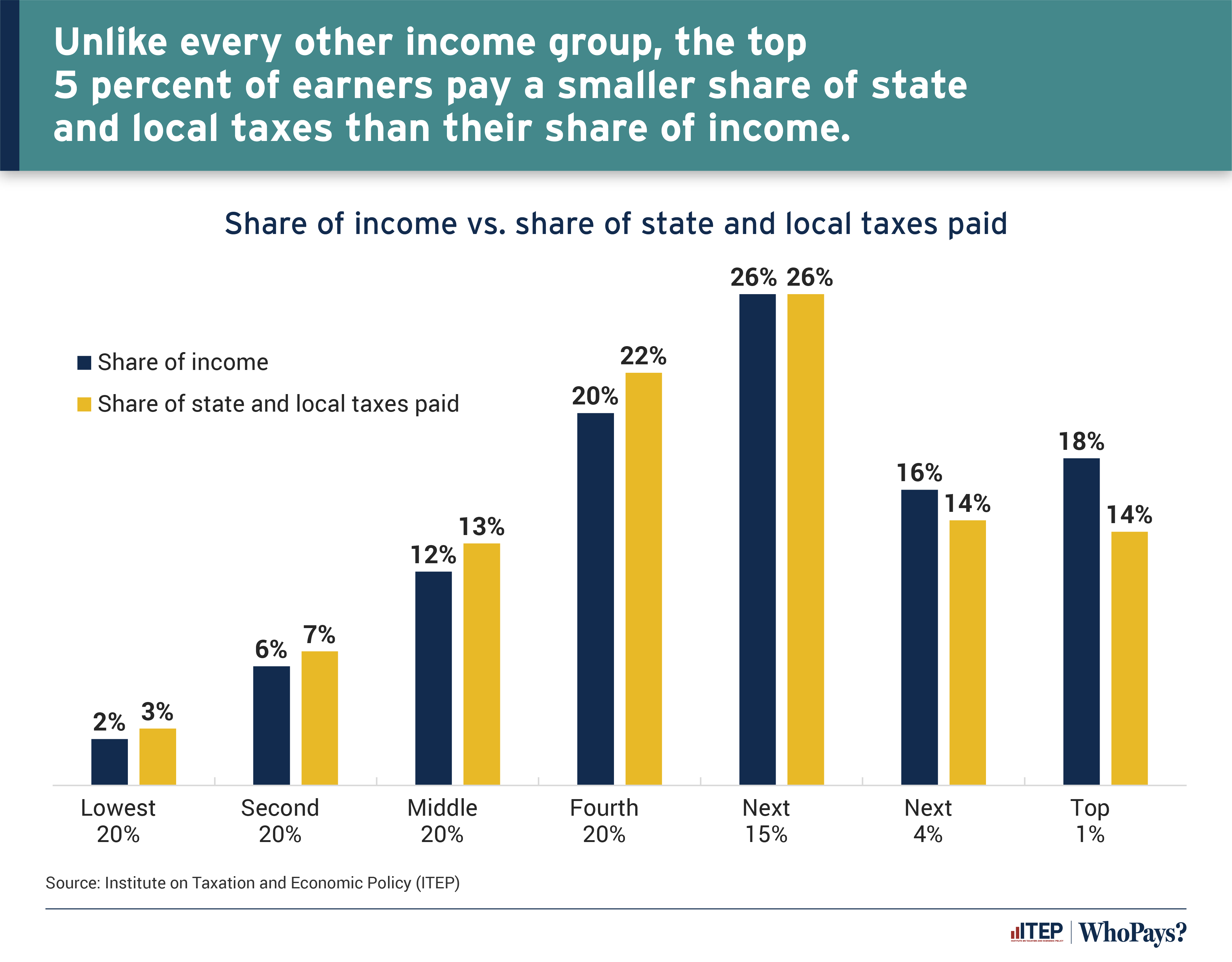

The nation’s income is concentrated at the top. For example, the top 1 percent alone have a combined income that exceeds that of the bottom half of individuals and families.

Despite this imbalance, state and local tax systems typically ask less of high-income families than of families of more modest means. The top 5 percent of earners pay a smaller share of state and local taxes than their share of income. By contrast, the bottom 80 percent of families pay out a larger share of state and local taxes than the share of income they bring in.

Note: These figures are based on a national average of total state and local tax payments over total income, grouped according to each state’s distribution of income. Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

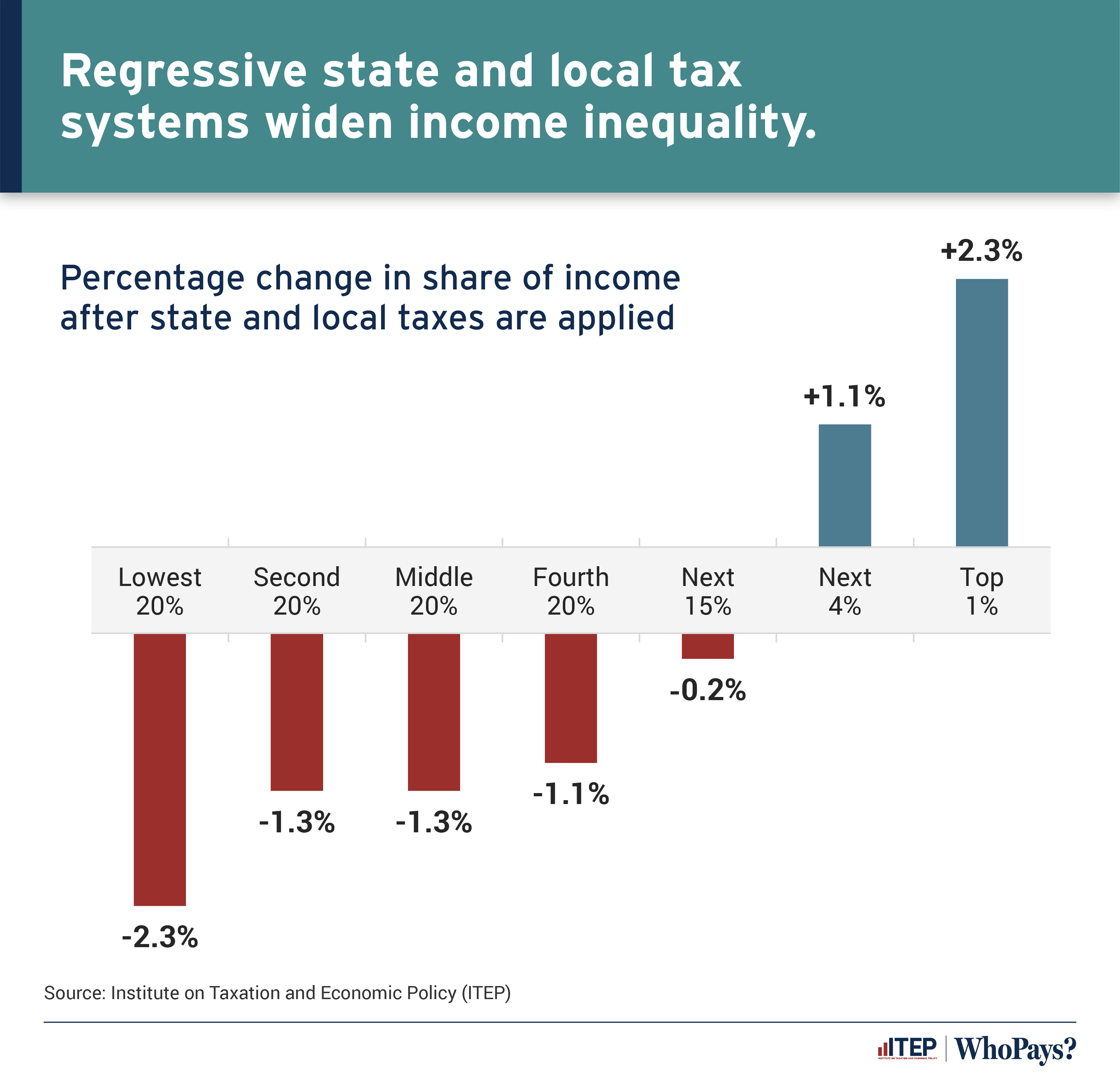

Most state and local tax laws exacerbate income inequality.

Because low- and middle-income individuals and families face above-average state and local tax rates, their share of total income falls after state and local taxes are collected. Low-income families, for example, see their share of income fall by 2.3 percent, while high-income families experience a 2.3 percent gain in their share of income after these taxes are collected.

In other words, incomes are less equal after state and local taxes are applied than before.

Note: These figures are based on a national average of total income before and after state and local tax payments, grouped according to each state’s distribution of income. Figures are expressed as percentages rather than percentage-point changes.

Personal income tax returns reveal how much individuals and families pay in income taxes. But most taxpayers cannot measure how much sales and excise tax they pay on purchases made each year. As it turns out, middle- and low-income taxpayers typically pay more taxes to their state and local governments based on what they buy (sales and excise taxes) than on what they earn (income taxes).

Proponents of state income tax cuts often overlook or ignore this fact, and frequently intensify it by swapping lower income taxes for higher sales and excise taxes. Proposals to decrease income taxes that largely impact the wealthy while increasing sales and excise taxes that ask more of families of more modest means worsen the upside-down nature of state tax codes.

Note: These figures are a national average of total state and local tax payments over total income, grouped according to each state’s distribution of income. Income tax category includes both personal and corporate income taxes.

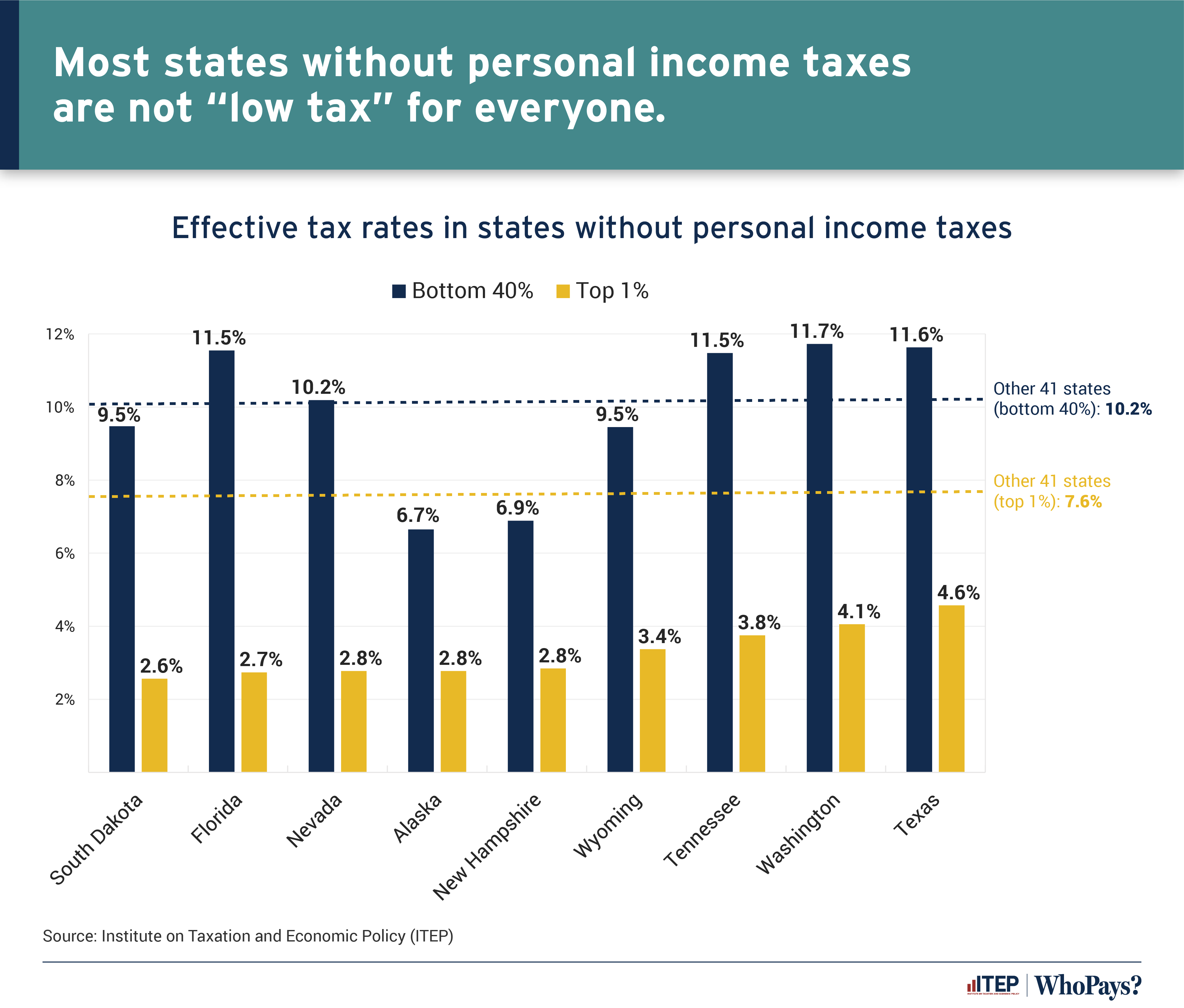

It is a misconception that states without personal income taxes are “low tax.” In reality, to compensate for the lack of income tax revenues these governments often rely more heavily on sales and excise taxes paid by lower-income families. As a result, while the nine states without broad-based personal income taxes are universally “low tax” for households with high incomes, these states tend to be high tax for the poor.

Note: The nine states without broad-based personal income taxes are Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming.

The nine states without broad-based personal income taxes are, without exception, the lowest-tax states in the nation for high-income families, with total tax rates for the top 1 percent averaging 3.3 percent and never exceeding 4.6 percent. Yet five of these nine states require their low- and moderate-income taxpayers (those in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution) to pay more than 10 percent of their income in state and local taxes each year.

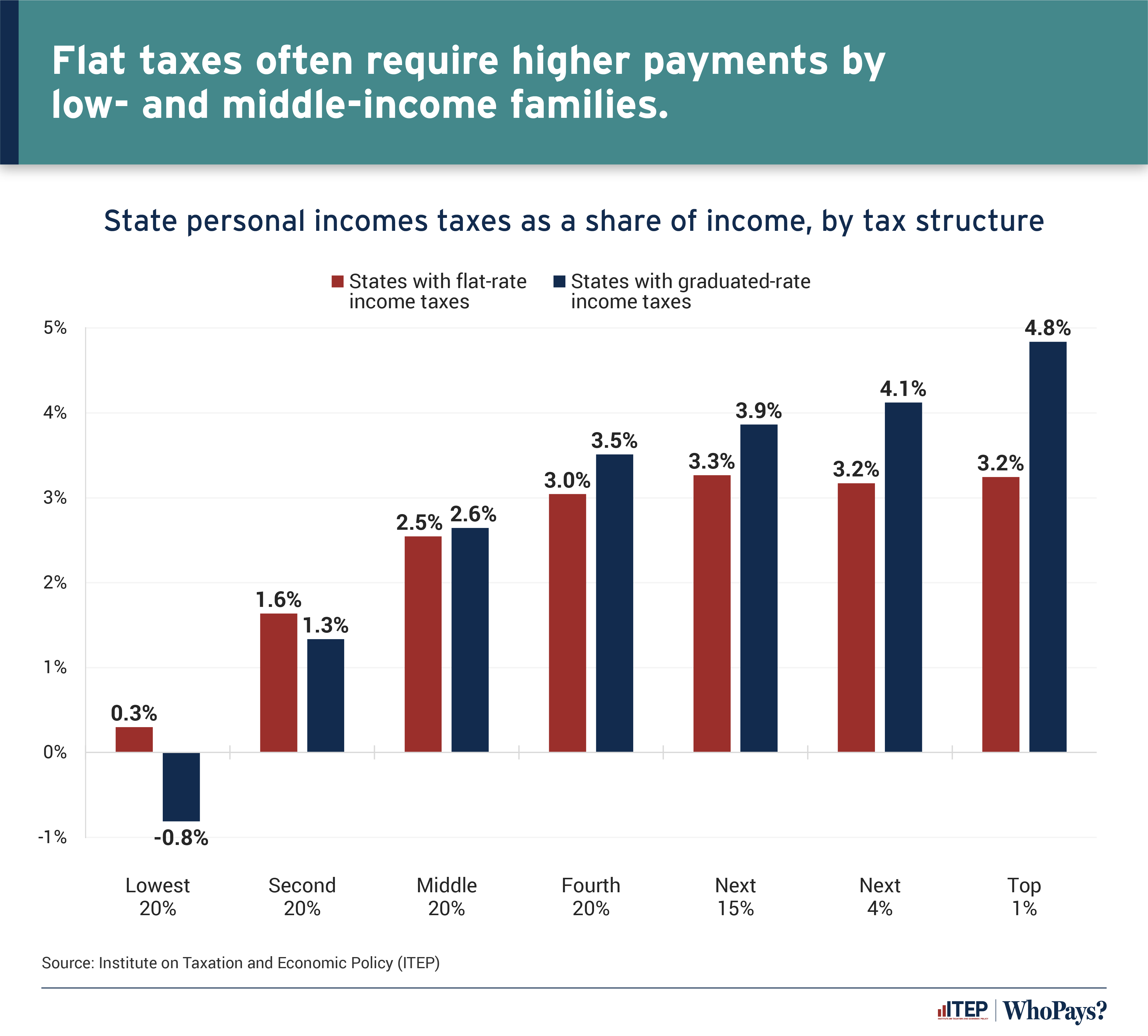

States taxing personal income take one of two general approaches: a flat rate applied to all taxable income or a graduated system in which higher rates apply to higher income levels. Graduated-rate income taxes tend to be more progressive than flat-rate taxes.

Because they allow states to collect more revenue from high-income taxpayers, graduated-rate taxes also typically allow for lower tax bills for low-income families and overall have about the same rates for middle-income households.

Note: Of 41 states with broad-based state personal income taxes, twelve levy flat-rate taxes and 29 (plus the District of Columbia) levy taxes with a graduated rate structure. The states with flat-rate taxes are Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Utah. Iowa is represented with its current law, but by 2027 will have a flat rate.

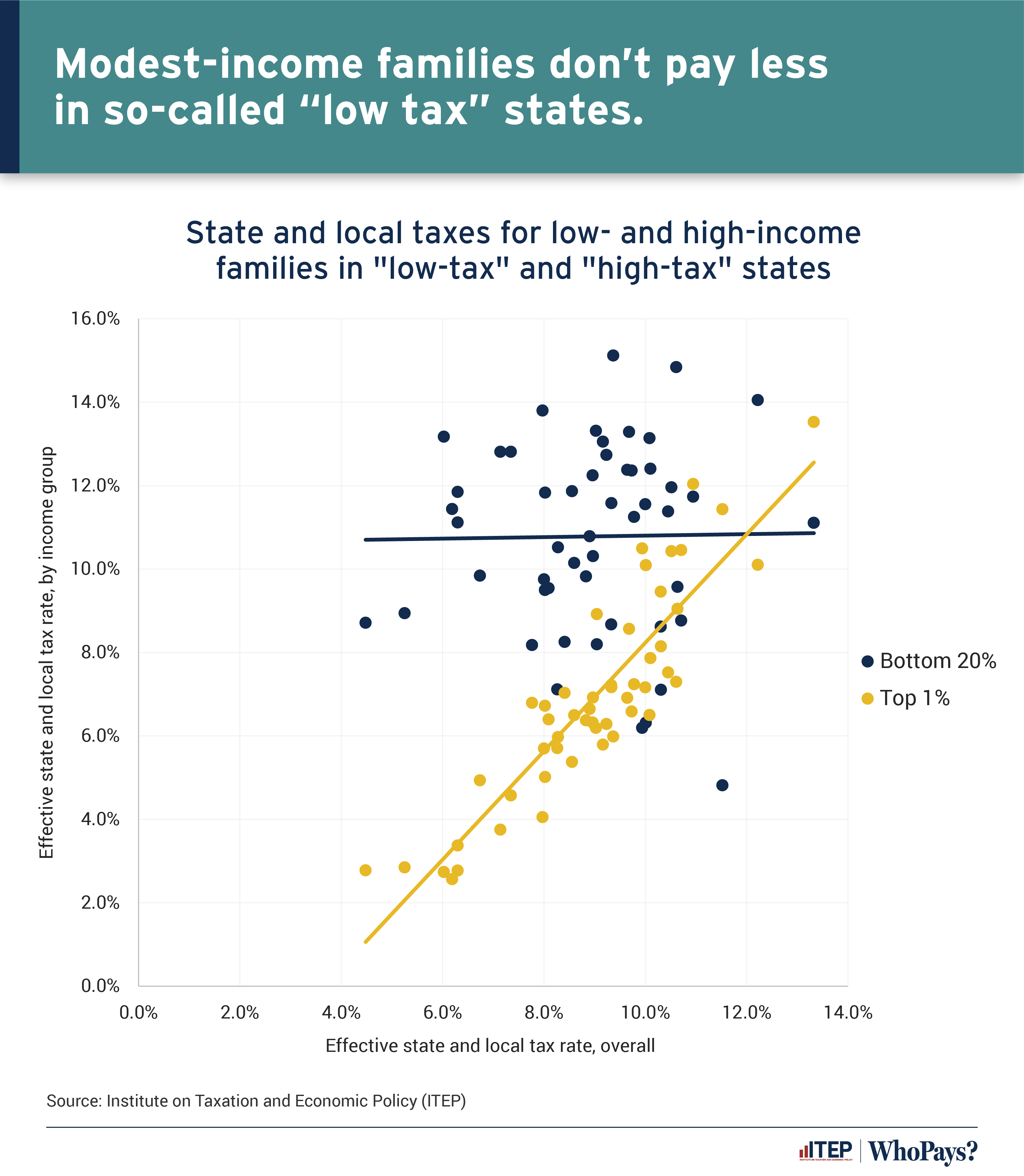

State and local taxes paid by the wealthiest residents vary from 4.5 percent of total income in oil-rich Alaska to 13.3 percent in New York. However, families with very modest incomes do not pay less in states with lower overall state and local taxes.

Overall, the correlation between the average state and local tax rate and that of those in the bottom 20 percent is 0.01 (no significant correlation). For the highest 1 percent it is 0.90 (very strong correlation). There are only 4 states where there top 1 percent pay at least their state’s average rate: California, Minnesota, New York, and Vermont.

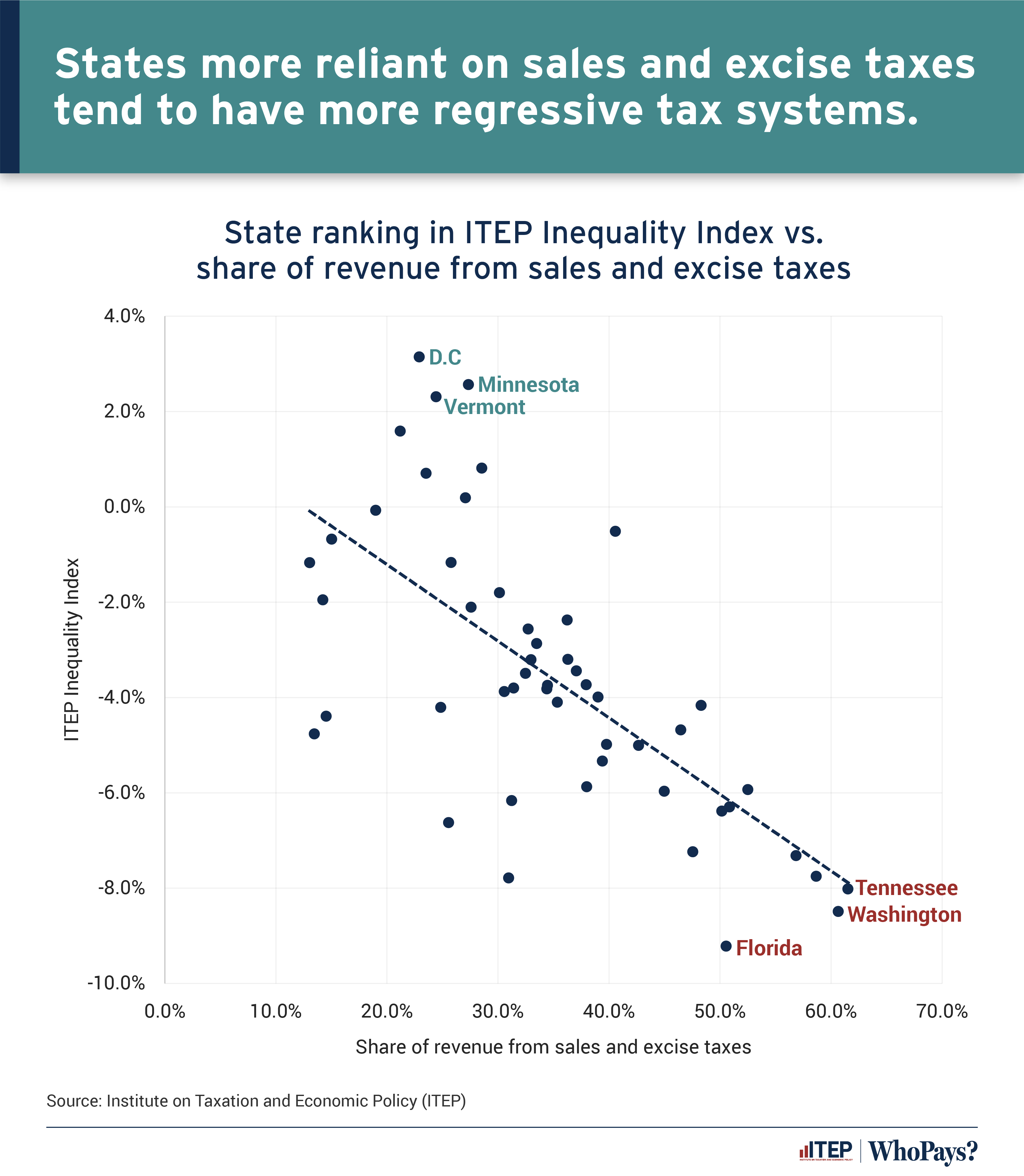

Overreliance on sales and excise taxes to raise revenue is a key feature of regressive tax systems. States where a significant share of revenue comes from taxes on consumption tend to receive lower scores in ITEP’s Tax Inequality Index, meaning that taxes fall disproportionately on low- and middle-income families rather than on families with large incomes.

Note: Reliance on state and local sales and excise taxes is measured as explained in Appendix C of Who Pays? 7th edition. An explanation of how the ITEP Tax Inequality Index is calculated is available in the methodology section of ITEP’s Who Pays? report.

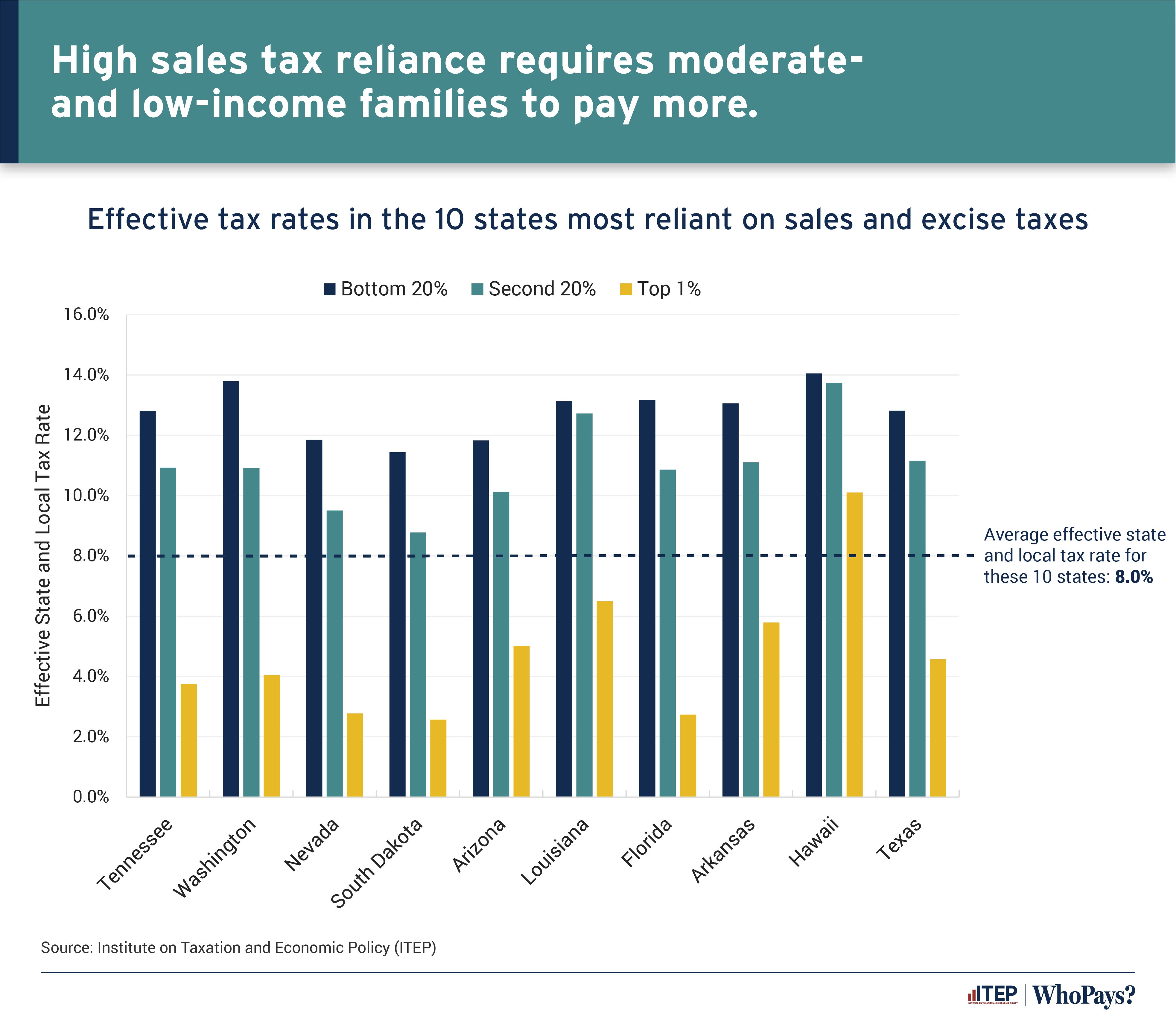

The pattern is clear in the states most reliant on sales and excise taxes. Because these taxes, also known as consumption taxes, fall more heavily on families with modest incomes, those families pay much higher overall tax rates in these states.

Even though these states collectively have slightly lower state and local taxes than the national average (8.0 percent compared to 9.3 percent), the bottom 20 percent in each of these states pays above the national average without exception, and the second 20 percent pays less than the national average only in South Dakota.

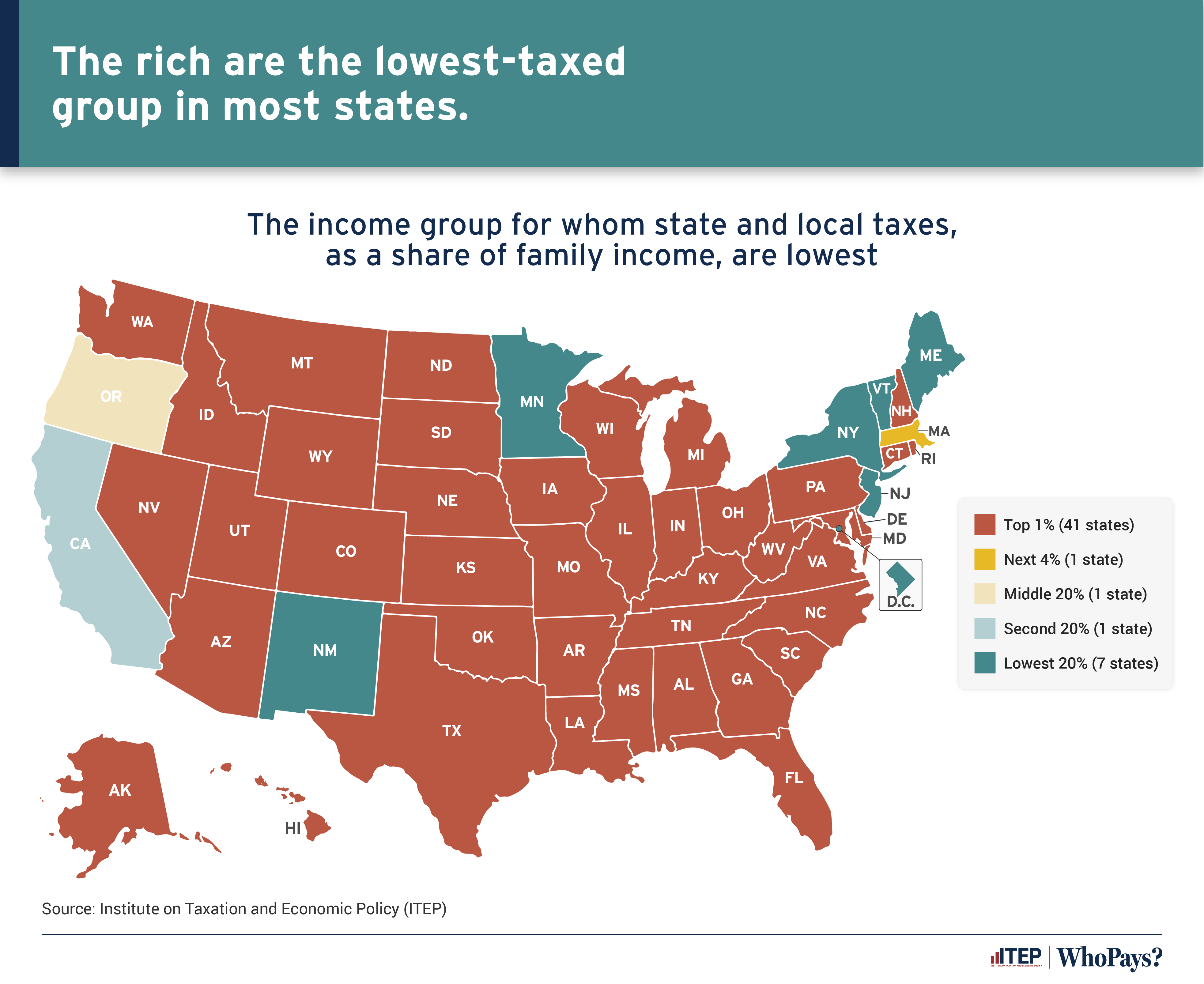

Most states have chosen to make the highest-income households the least responsible for paying a fair share toward state and local government operations. Only nine states and D.C. have chosen to tax any other income group lower than the top 1 percent. And in one of those states, Massachusetts, the lowest taxed are the four percent of earners right behind the top one percent.

Six states and D.C. are directly confronting income inequality by having the bottom fifth of earners pay the lowest taxes: D.C., Maine, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, and Vermont.

The ITEP Tax Inequality Index measures the effects of each state’s tax system on income inequality. It examines whether the gap in families’ shares of income is wider or narrower after state and local taxes. States with regressive tax structures have negative inequality index scores, meaning that incomes are less equal in those states after state and local taxes than before. The farther the score falls below zero, the more regressive the tax code.

Of the 10 most regressive state and local tax systems in the nation, eight levy either a flat income tax or no personal income tax at all. By contrast, the 10 least regressive states (including seven states with moderately progressive codes) all use graduated-rate personal income taxes.

Note: An explanation of how the ITEP Tax Inequality Index is calculated is available in the methodology section of ITEP’s Who Pays? report.