On Tuesday night, 25 Republicans joined nearly all the chamber’s Democrats to approve the Corporate Transparency Act, a bill that would require those creating a company to report its owners to the federal government. The White House expressed support but called for the House and Senate to work on certain details.

Currently, each state has its own rules and requirements to incorporate and several states allow individuals to have representatives create companies on their behalves without ever identifying the true owner. This has proven hugely problematic because law enforcement officials pursuing tax evasion, money laundering or even terrorist financing sometimes cannot figure out who really owns the entities used to hide money and move illicit profits.

Good government advocates and groups representing law enforcement like the Fraternal Order of Police pushed Congress for years to address the problem. Earlier efforts to require states to collect identifying information foundered. The bill just approved by the House would instead require those registering a company to provide information about the entities’ owners to the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), which would make the information available to law enforcement officials upon request.

This reform is long in coming. In hearings a decade ago, then-Senator Carl Levin of Michigan explained how state governments were assisting criminal activity by allowing people to create business entities under their laws without identifying the owners.

Sen. Levin told of a single company created in Delaware that Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) investigated after learning they had made suspicious wire transfers of $150 million. ICE found that the company was part of a web of more than 800 entities across the country that were controlled by companies in Panama and that seemed to be shifting a huge amount of funds around. But investigators could not learn anything more because Delaware refuses to collect any information that would identify the owners of the companies created under its laws.

Another similar case described by Levin involved Viktor Bout, a Russian arms dealer who moved millions of dollars around in companies created in Florida, Texas and Delaware. He was indicted in 2008 for conspiracy to kill United States nationals, the acquisition and use of anti-aircraft missiles, and providing material support to terrorists. But in many (probably most) cases, criminals using shell companies are never identified.

In March, the group Global Financial Integrity released a study demonstrating that, in every state, applying for a library card requires more identifying information than setting up a new company. Global Financial Integrity is part of the FACT Coalition, which has worked tirelessly to advocate for the Corporate Transparency Act.

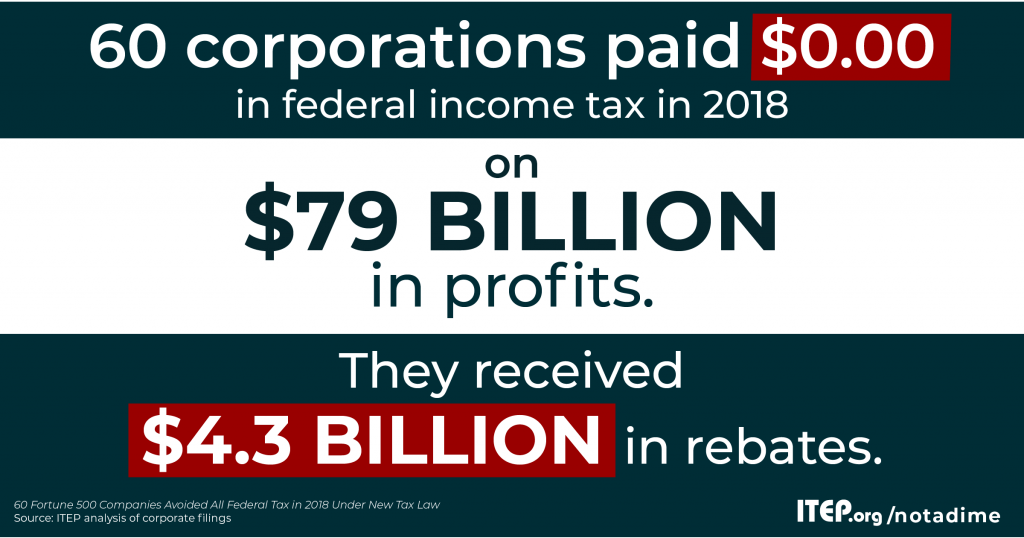

The bill would exempt publicly traded companies, larger companies and those with at least 20 employees in the U.S., which are unlikely to serve as shell companies for illegal activities. (Rather than evading taxes by hiding income from the IRS, large corporations are more likely to avoid taxes by using the special breaks and loopholes that misguided lawmakers created in our tax laws.) The Corporate Transparency Act cracks down on companies that facilitate crimes–tax evasion (hiding income from the IRS), money laundering and financing criminal activities.

The existing patchwork of lenient state laws has made the U.S. a major tax haven for people all over the world. For years, the U.S. has asked other governments to stop facilitating offshore tax evasion by Americans but has done little to stamp out the same practices here in the U.S. Enacting the Corporate Transparency Act could make it easier for the U.S. to obtain cooperation from other countries in cracking down on tax evasion and other cross-border crimes.