Combined reporting requires corporations with multistate operations to report all their revenues and expenses together, making it harder for them to avoid state taxes by moving money around.

This policy mainly affects very large companies, and it helps those states that use it to collect billions in tax revenue to fund services like education, public safety, and infrastructure that businesses and their employees rely on.

To reduce tax avoidance further, states are considering extending combined reporting to corporations’ foreign subsidiaries.

Profitable corporations should pay income tax to each state where they do business, roughly in proportion to their economic activity in that state. For small, single-state businesses, this is straightforward: All profits are taxable where the company operates.

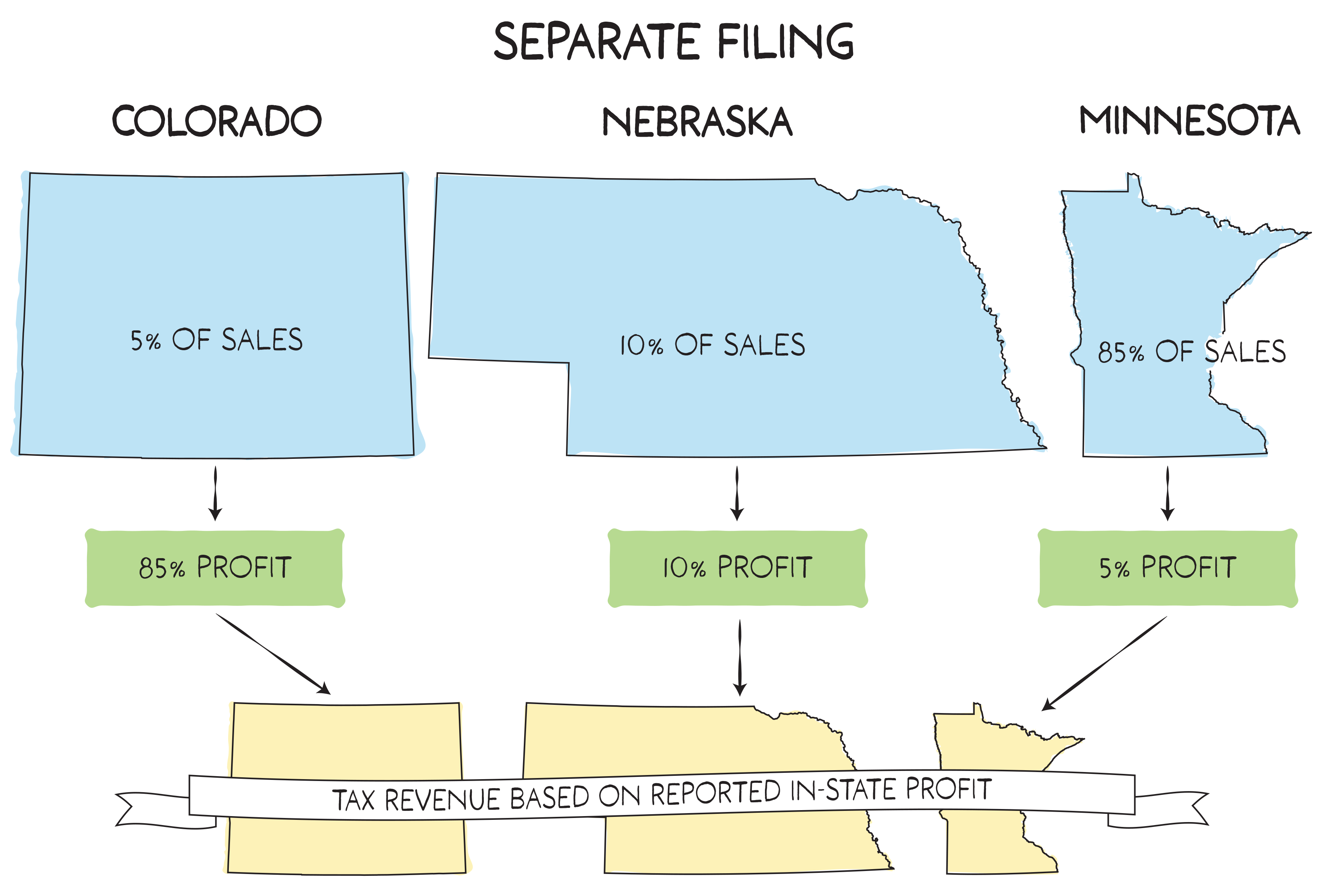

For large corporations with operations across multiple states, though, determining where profits are “earned” is not so easy. Corporations are more able to engage in tax avoidance in states that follow the antiquated separate accounting rule, a relic of an era when businesses were organized more simply. This rule allows a corporation to report the profits of each of its subsidiaries independently. Avoidance occurs under this system because companies can structure their operations so that some subsidiaries avoid taxation entirely, or they can use accounting techniques to shift profits between states to minimize their tax burden.

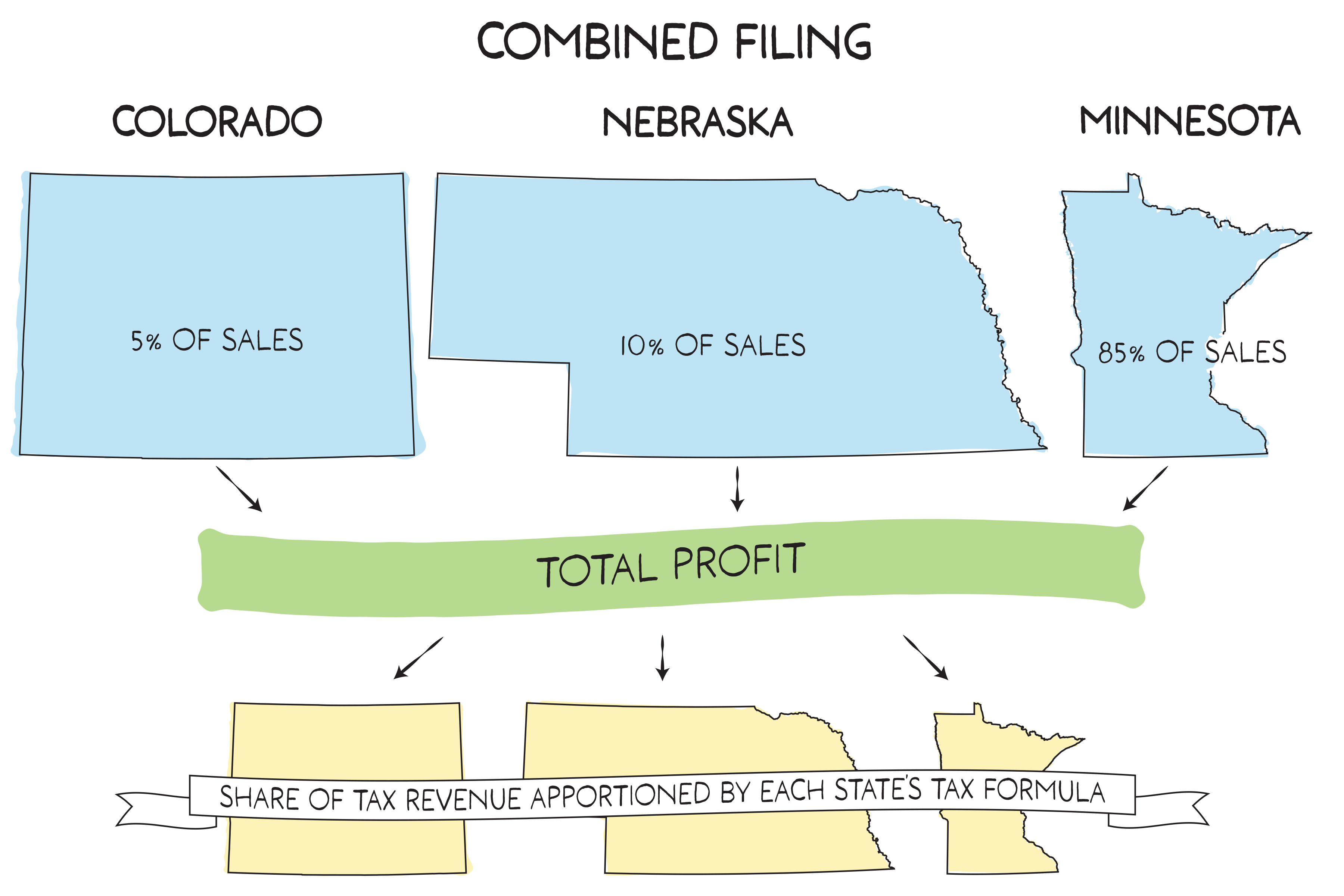

The modern alternative to separate accounting is mandatory combined reporting. This rule requires multistate corporations to add together the profits of the parent company and subsidiaries into a single report, regardless of where those subsidiaries are located. This approach recognizes that all parts of a corporation contribute to its overall profitability.

Consider a corporation with subsidiaries in three states. Under separate accounting, each state taxes only the profits of subsidiaries with sufficient in-state economic presence (“nexus”), even if out-of-state subsidiaries generate most of the company’s profits. Combined reporting requires the corporation to report all subsidiary profits as one total. More than half of states with corporate income taxes now use some form of combined reporting.

Which Businesses Are Affected?

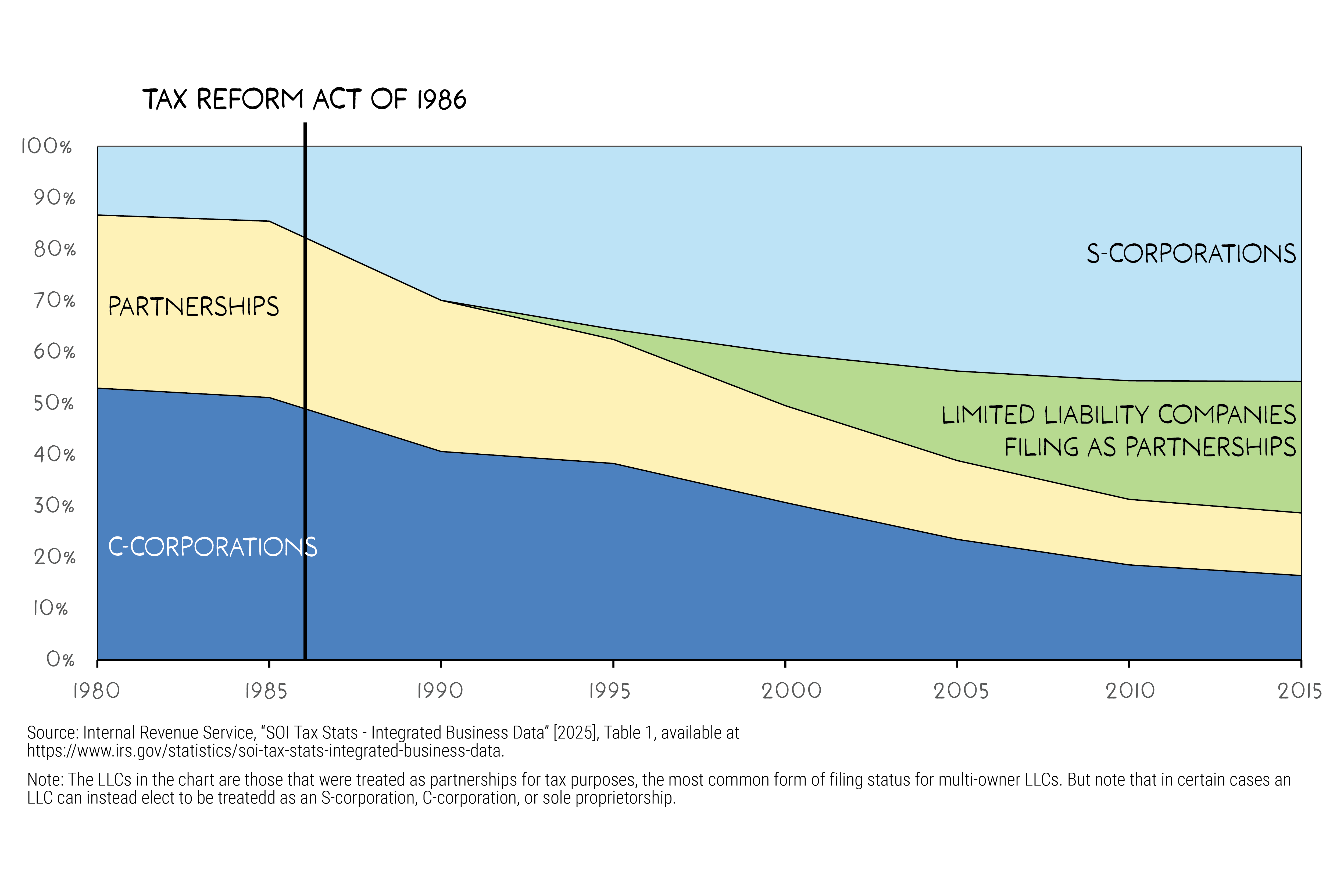

Combined reporting affects only a small fraction of all businesses. Most companies are pass-through entities (partnerships, LLCs, S corporations) that already do business as a single entity. Only C corporations, which are about 5 percent of U.S. businesses albeit some of its largest and most profitable ones, face changes under combined reporting. Even among profitable C corporations, only those that operate across multiple states and are structured as a parent company with one or more subsidiaries and currently benefit from separate accounting are affected.

How Separate Accounting Enables Tax Avoidance

Separate accounting creates numerous opportunities for tax avoidance. One common example relies on abusive “transfer pricing” within the corporate group. A parent company, say, a manufacturer, sets up a subsidiary in a state without an income tax to own the factory that does the actual manufacturing. The parent acts as the wholesaling arm of the company. The subsidiary charges the parent an artificially high price for the product, so that most of the profit shows up in the no-income-tax state and very little in the states where the product is warehoused before it’s sold to retailers. The company takes advantage of an obscure federal law that prevents the manufacturing subsidiary from being taxable in the state(s) where the product is eventually sold.

Through this accounting maneuver, profitable corporations can dramatically reduce or eliminate their state tax obligations. Major manufacturers have used variations of this strategy for decades.

Combined Reporting: A Comprehensive Solution

Combined reporting eliminates these accounting gimmicks by treating related companies as a single economic unit. If a corporation tries to use the transfer pricing strategy under combined reporting, the manufacturing subsidiary’s artificially high “income” would be added back to the parent’s profit and offset by the parent company’s artificially high “expense,” resulting in no net change to taxable profits. In other words, taxable profits in the state would depend only on sales made to and purchases of inputs from independent customers/suppliers – not other members of the corporate group.

States could address tax avoidance by closing loopholes individually, and some have enacted targeted legislation against specific schemes. However, this piecemeal approach faces a fundamental limitation: corporate accountants continuously develop new tax avoidance strategies. Combined reporting provides a single, comprehensive solution that prevents all forms of income-shifting between related entities.

Leveling the Playing Field

Combined reporting creates greater fairness in the tax system. Small businesses operating in single states lack resources to set up complex organizational structures to reduce their taxes; they simply pay taxes on their profits where they earn them. Large corporations shouldn’t gain tax advantages merely because they can afford sophisticated accounting schemes.

The policy also ensures that a company’s tax obligation doesn’t change based on how it organizes its corporate structure. A business earning $10 million in profits should face similar tax treatment whether it operates as one entity or divides operations among multiple subsidiaries.

The additional revenues raised by combined reporting allow states to fund public services without raising tax rates on compliant businesses or implementing less efficient revenue measures. The policy essentially ensures that profitable corporations contribute their intended share for the infrastructure, education systems, and legal frameworks that enable their success.

The Worldwide vs. Water’s Edge Distinction

Even states with combined reporting can strengthen their systems further. Most limit their requirements to the “water’s edge” of U.S. borders, allowing corporations to shift income to foreign tax havens.

A policy known as “worldwide combined reporting” addresses this gap by including all subsidiaries globally. It’s an approach that was common in state corporate income taxes before the 1980s, when the federal government threatened to ban it and states responded by scaling it back. Several states already allow corporations the option of filing taxes this way; restoring mandatory worldwide combined reporting would result in a far more principled administration of the tax law while also increasing state corporate tax revenues by an estimated 14 percent.

Related Entries

How Do State Corporate Income Taxes Work?

A robust corporate income tax ensures that profitable corporations help fund the public services they benefit from, just as working people do. It’s one of the few progressive taxes available to state policymakers.

How Do States Tax the Profits of Pass-through Entities?

Most businesses are not liable for corporate income tax on their profits. Instead, federal and state tax laws allow them to choose a structure such as partnerships, sole proprietorships, and S corporations under which their profits are passed through to their owners for taxation. These “pass-through entities” benefit from state-funded services like schools, infrastructure, and public safety, and their owners are generally wealthy, so taxing them fairly – at a minimum ensuring that pass-through income is taxed at the same rate as wages – is essential to a sound and equitable revenue system.

Learn More

- Davis, Carl, Matthew Gardner, and Michael Mazerov (2025). “A Revenue Analysis of Worldwide Combined Reporting in the States.” ITEP.

- Davis, Carl, and Matthew Gardner (2023). “Far From Radical: State Corporate Income Taxes Already Often Look Beyond the Water’s Edge.” ITEP.

- Shanske, Darien, Michael Mazerov, and Peter D. Enrich (2025)., “Model Statute for Worldwide Combined Reporting.” SSRN.