A current policy baseline analysis of the tax provisions of H.R. 1

In analyzing the impact of the tax and spending megabill signed into law by President Trump on July 4 there is a difference between the approach that makes the most sense for understanding the impact on the federal budget and another approach that might make more sense for individuals thinking about their own tax bills.

As ITEP has previously found, the megabill will reduce revenue by nearly $570 billion in calendar year 2026 alone compared to what would happen if Congress did nothing. This is using what is called the “current law baseline,” which is the most sensible way to measure a policy change’s budgetary effects.

However, taxpayers seeking to understand how their taxes will change next year compared to what they are currently paying may find that using what is called the “current policy baseline,” which measures the new policy compared to the policy in place right now, is more intuitive.

The analysis below explains how individuals and families will see their taxes change in 2026 as a result of the new law.1 (ITEP previously analyzed the law’s distributional effects using a current law baseline; the findings below are intended to add more context to Americans’ understanding of how the law will affect them.)

Key findings

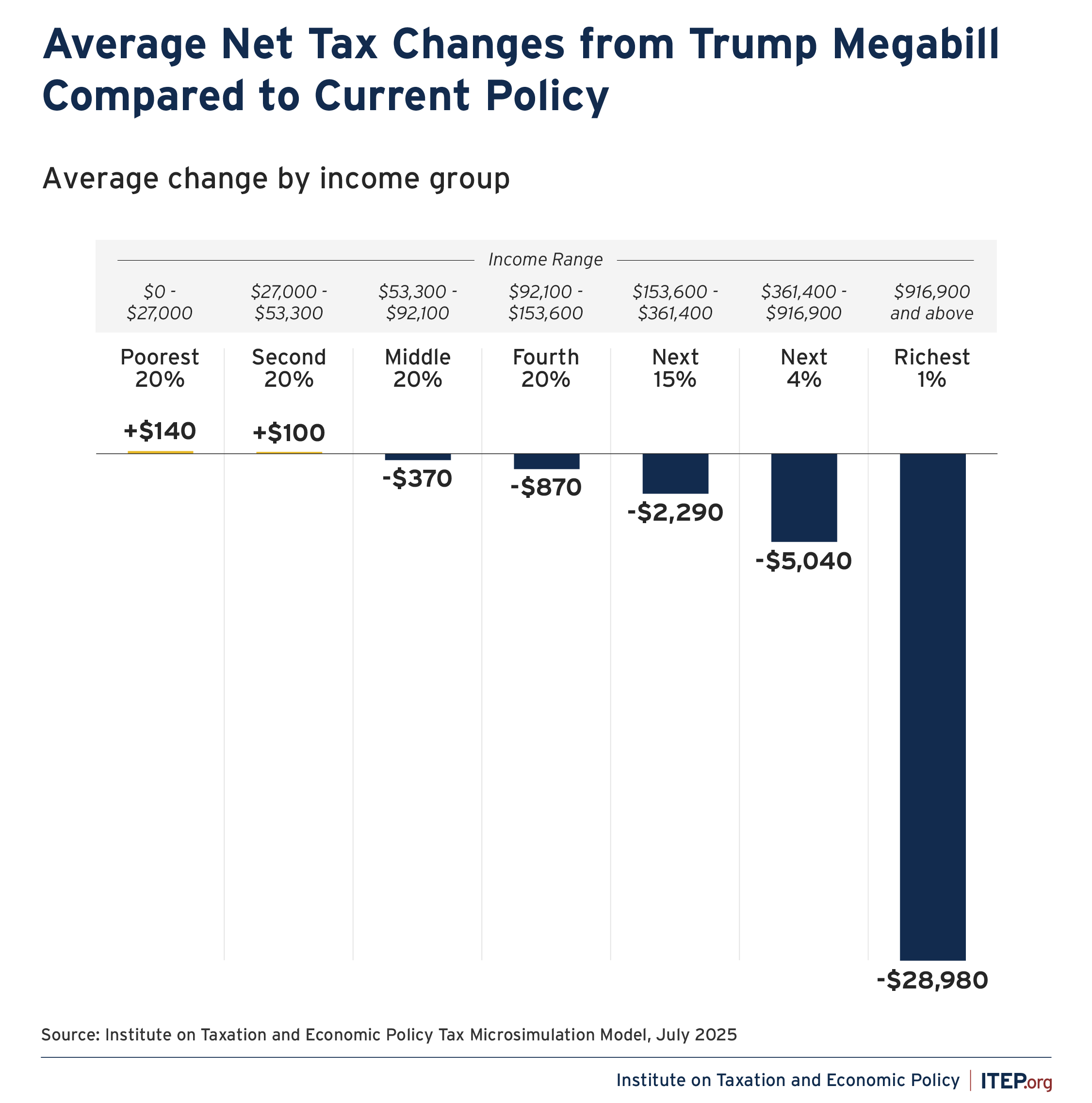

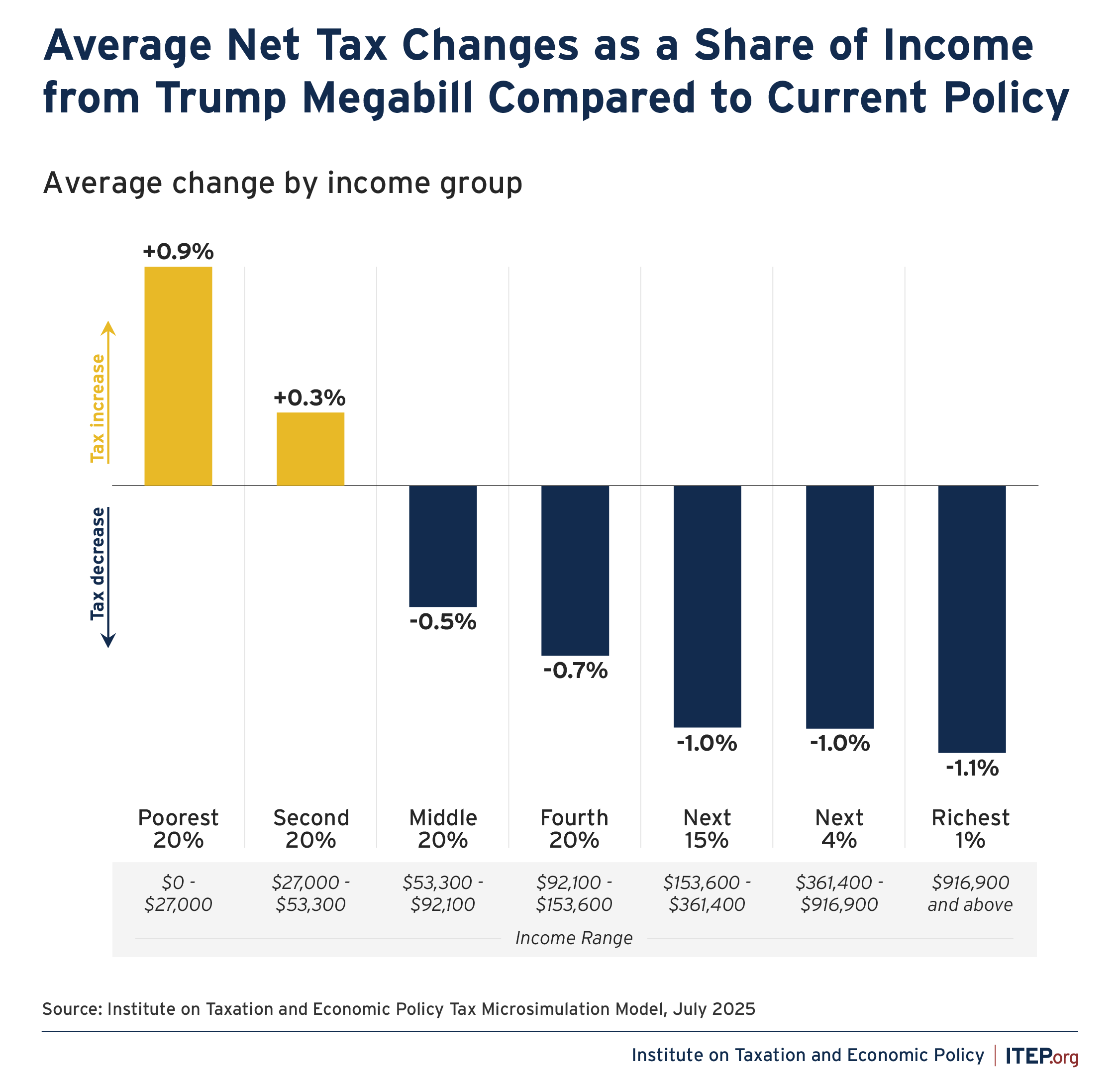

- The megabill will raise taxes on the poorest 40 percent of Americans, barely cut them for the middle 20 percent, and cut them tremendously for the wealthiest Americans compared to the tax situations faced by Americans this year.

- This tax increase for the poorest Americans is largely attributable to lawmakers’ decision not to extend enhancements to health care tax credits that make health insurance more affordable.

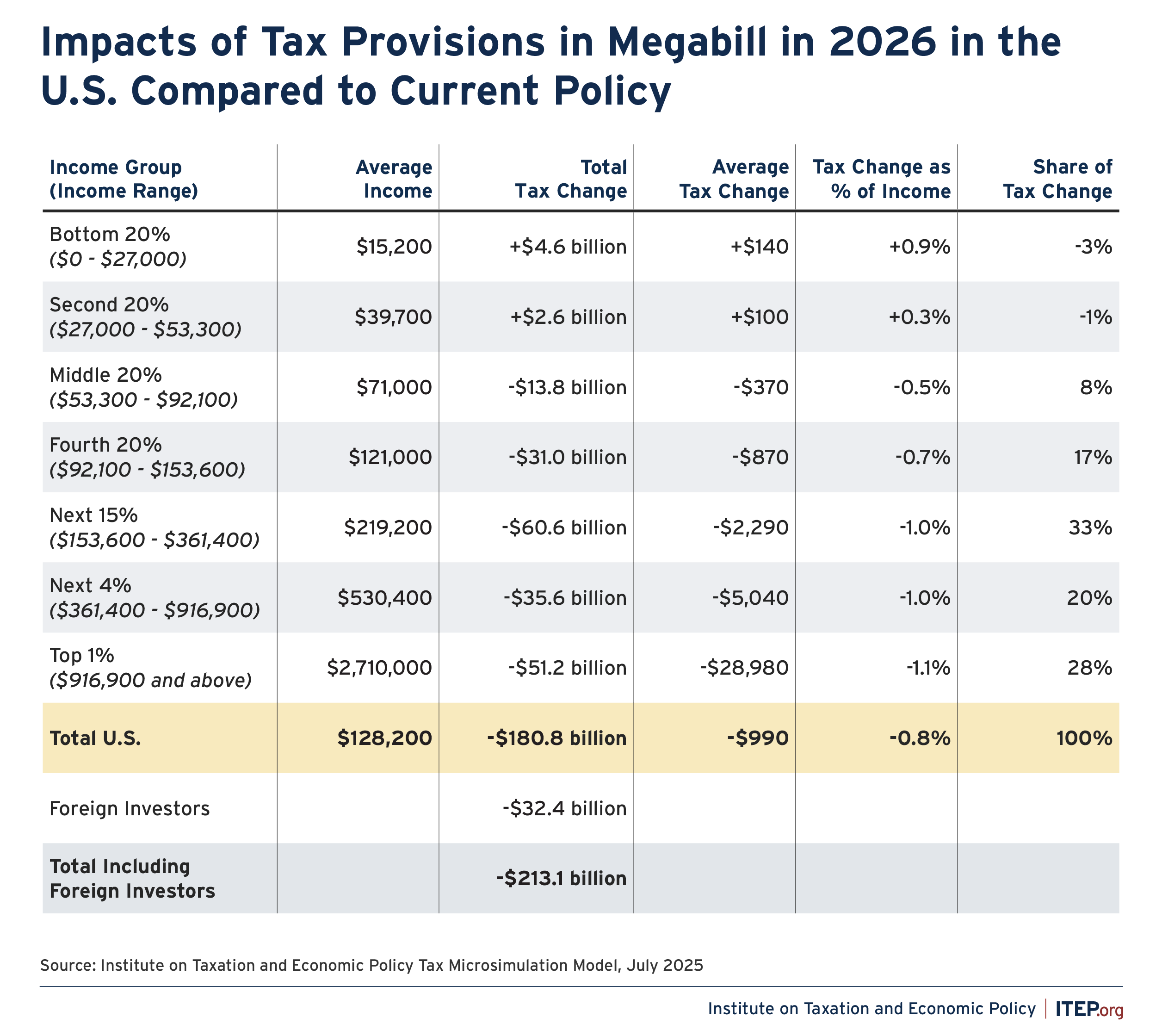

- The richest 1 percent of Americans alone will benefit more than the bottom 80 percent of Americans, receiving a total net tax cut in 2026 that is about $14 billion greater than the poorest 40 percent, the middle 20 percent and the next 20 percent of Americans combined.

- Even foreign investors who own shares in U.S. companies will benefit more than most Americans. These foreign investors will receive more in net tax cuts in 2026 than the middle 20 percent and poorest 40 percent of Americans combined.

- For Americans with modest incomes and middle-class Americans, those cuts will be quite small and, in some cases, will be completely outstripped by the Trump administration’s higher import taxes, or tariffs. For example, even before considering the tariffs, the poorest 20 percent will see an average tax increase of $140 compared to what they currently pay. The middle 20 percent will see a tax increase in some states and, on average nationwide, will see a tax cut of $370 compared to what they now pay.

- In 44 states, the poorest 20 percent or poorest 40 percent of taxpayers would see a tax increase in 2026 compared to this year. In four states – Alabama, Florida, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – the middle 20 percent of taxpayers would also see a tax hike. And in three other states – the District of Columbia, Minnesota, and New York – all income groups would see a tax cut, though the average annual cut for the poorest 20 percent would be quite low (effectively $0, $80, and $20, respectively).

These figures do not include other potential costs to families in the new law, such as deep cuts to Medicaid and food assistance. These cuts will have adverse health and financial implications for families that directly benefit from these programs. The cuts will also harm others in communities that are broadly dependent on these funding streams—such as rural communities, which will see hospital closings.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Current Law Baseline vs. Current Policy Baseline

Common sense would suggest that when lawmakers consider the budgetary impacts of tax legislation, they would compare what the federal budget would look like if the legislation were enacted to how the budget would look if it were not enacted. And this is traditionally what Congress has done. This is sometimes called comparing legislation to current law, or a “current law baseline.”

But when considering the question of how Americans’ taxes will be changed by legislation compared to what Americans are paying now, common sense might lead to a different approach, which compares the tax code that would exist under the legislation to the tax code in effect this year, even if many of the tax rules in effect this year are supposed to expire according to the laws on the books right now. This is sometimes called comparing legislation to current policy, or a “current policy baseline.”

The proper approach for understanding legislation’s budgetary effects, meaning its effects on revenue, spending, and deficits, is to compare the legislation to current law.

For Americans seeking to understand how the legislation will impact them, however, the lens they naturally tend to bring to that question is a comparison to the current policy environment under which they have become accustomed to paying taxes.

In the debate leading up to, and following, the enactment of Trump’s megabill, Congressional Republicans have done the exact opposite.

Congress’ official revenue estimators at the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) provide revenue estimates by fiscal year and for the following 10 fiscal years. Congressional Republicans made several of their new tax breaks temporary (even though they almost surely intend to make most of them permanent) which makes their tax changes appear less costly than they ultimately will be. Nevertheless, JCT’s 10-year estimate of the revenue impact of tax legislation is the most useful guide to lawmakers considering the fiscal impacts of a proposal.

In the debate leading to enactment of the megabill, Congressional Republicans went even further in hiding the cost of their tax proposals, this time using a revenue estimate from JCT that compared the tax provisions in the megabill to current policy rather than current law. This maneuver made trillions of costs officially disappear. JCT estimated that the tax provisions would reduce revenue over ten years by $4.5 trillion compared to current law, but by “only” $700 billion compared to current policy.2

Endnotes

- 1. Some of the highest profile tax changes, such as those affecting tips, overtime, and the state and local tax (SALT) deduction apply retroactively to Tax Year 2025, though taxpayers will generally not experience these effects until they file their 2025 tax returns next year. But while some of the bill’s changes relative to current policy take effect in 2025, looking ahead to Tax Year 2026 offers a fuller picture of the bill’s effects because other notable departures from current policy, such as new estate tax cuts and the expiration of premium tax credit enhancements, do not take effect until that year.

- 2. See JCT JCX-35-25 from July 1, 2025 (https://www.jct.gov/publications/2025/jcx-35-25/) and JCT JCX-34-25 from July 1, 2025 (https://www.jct.gov/publications/2025/jcx-34-25/)