Key Findings

- As of early 2024, 17 cities and counties have progressive taxes on high-price real estate sales, also known as “mansion taxes.” Several others are currently considering adopting these policies.

- Together these taxes raise nearly $3 billion in annual revenue, equipping communities with resources to make progress on critical priorities of local and national concern including housing, education, and infrastructure.

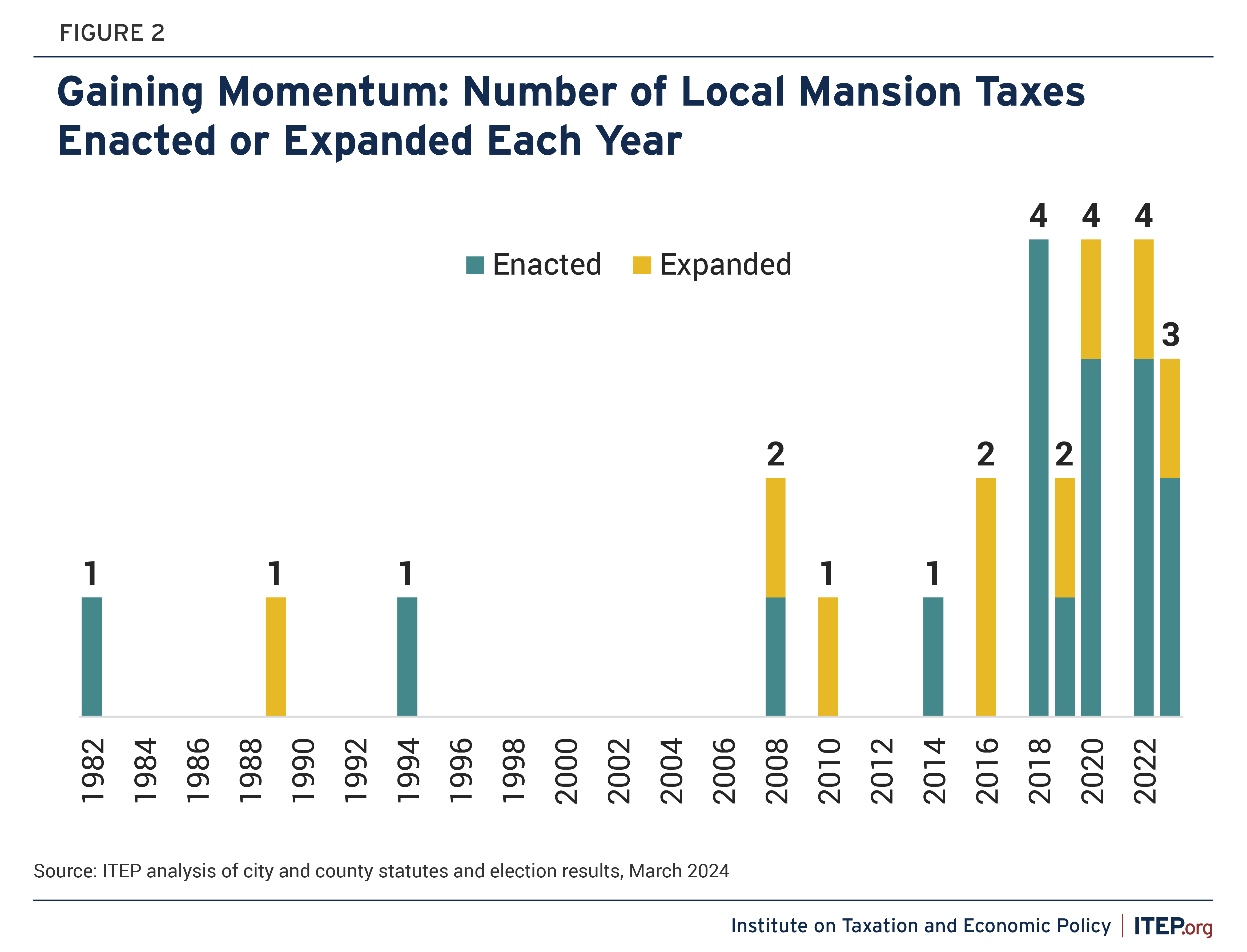

- Local mansion taxes have been around since 1982, but the momentum for them has built in recent years. Nearly all of today’s mansion taxes were enacted or expanded between 2018 and 2023.

- Local mansion taxes play an important role in rebalancing upside-down tax codes, advancing racial and economic equity, and raising new revenue to build more resilient and inclusive communities.

- Mansion taxes have proven popular with voters: When put on the ballot, measures to enact or expand mansion taxes have succeeded 86 percent of the time.[1]

Building homes and easing housing costs for working families. Improving public school facilities. Delivering shelter and stability to people in need. Investing in transit and infrastructure. Repairing the harms of structural racism. These are just a few of the ways cities and counties across the country are putting progressive real estate transfer taxes to work to achieve more resilient and inclusive communities.

More than one dozen cities and counties levy progressive taxes on high-price real estate transactions, and over a dozen more are considering such policies.[2] These taxes, sometimes called mansion taxes, are graduated one-time levies that apply when properties change hands. By asking buyers and sellers with greater financial means to contribute more fully to the common good, these policies are equipping communities with resources to make progress on critical challenges of local and national concern.

As momentum builds, lessons from the policies in place today can inform the steps ahead for communities across the U.S. This brief provides an overview of progressive local real estate transfer taxes as they currently exist — and details the positive role such measures can play in advancing economic and racial equity, building fairer and more robust local tax codes, and shaping better outcomes for communities and families.

Key features of local mansion taxes

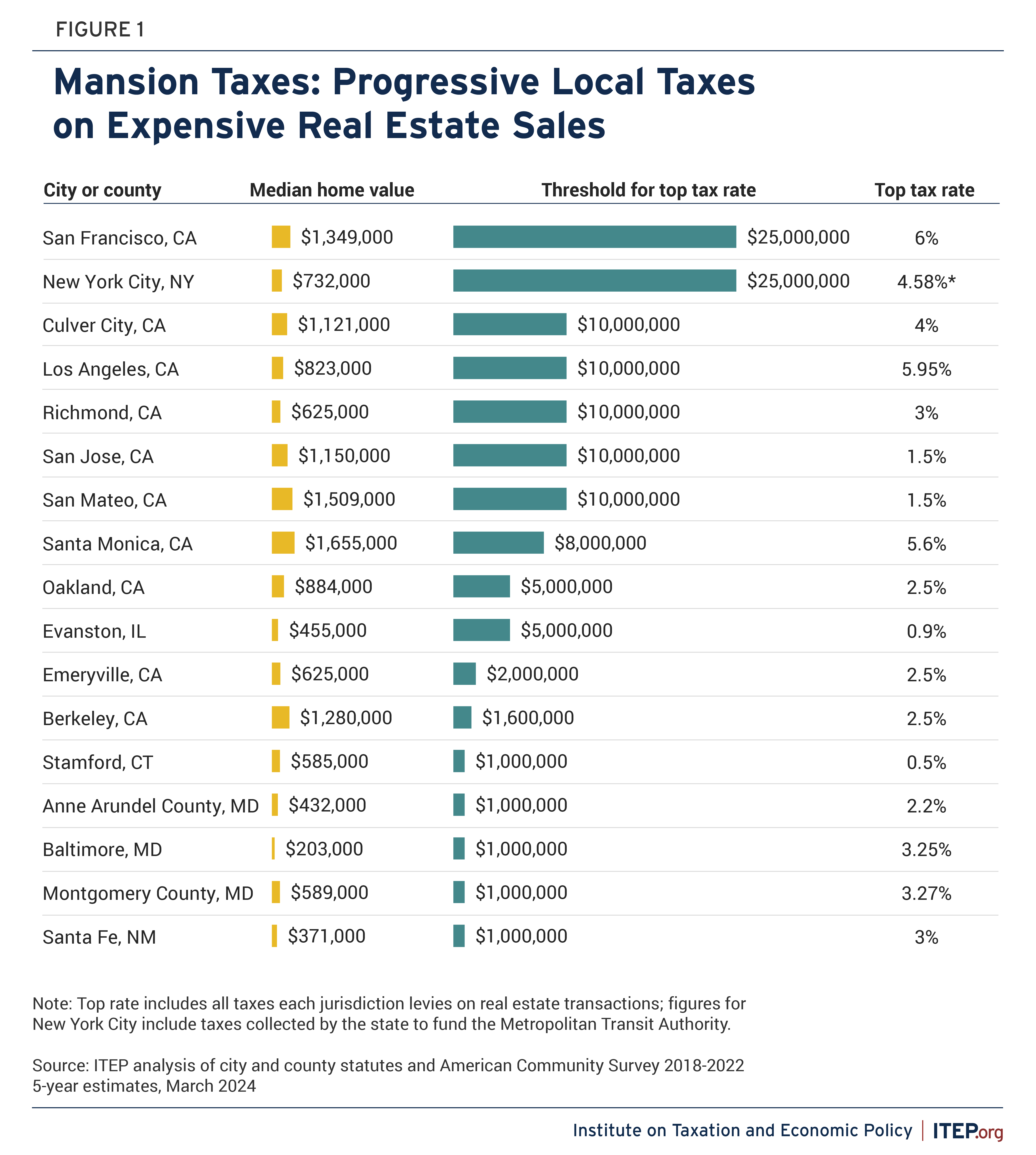

In 1982, New York City became the first locality in the nation to adopt a progressive tax on real estate transactions.[3] A total of 17 cities and counties have such taxes in place as of early 2024. They span six states and collectively raise nearly $3 billion in annual revenue for housing, transit, education, and other priorities.[4] The list includes the nation’s two largest cities by population, several midsize cities and counties, and lesser-populated jurisdictions with as few as 12,900 residents.

Progressive local real estate transfer taxes have grown increasingly popular in recent years. Of the 17 local mansion taxes in place as of early 2024, 16 have been adopted or expanded since 2018. These taxes have also proven popular with voters: When put on the ballot, measures to enact or expand mansion taxes have succeeded 86 percent of the time, our analysis of local election results shows.[5]

The progressive local real estate transfer taxes in place today share many features but differ in key details. Areas of variation between localities include tax rates, tax threshold levels, rate structures, the tax base, and how the revenue is used. These differences reflect diversities in real estate market activity, household wealth, local priorities, and other attributes.

- Tax rates and thresholds: Five of 17 localities levy top real estate transfer tax rates of 4 percent or more. In eight places the top rate is between 2 and 4 percent, and in four places it is 2 percent or less. Five localities apply their top tax rates to transactions worth $1 million and up, 10 have top tax rates that begin between $1 million and $10 million, and two reserve their highest tax rates for properties worth at least $25 million.

- Rate structure: Two localities, Santa Fe and Culver City, employ marginal tax brackets, applying their top tax rates only to the portion of a transaction’s value that exceeds a certain level. The remaining jurisdictions apply their tax rates to the full value of each transaction. The full-value approach leads to higher average tax rates and more revenue raised for properties sold above the threshold, while the marginal approach results in less variation in tax rates for transactions of similar value.

- Tax base: Most progressive local transfer taxes in place today apply to both residential and nonresidential property transactions. Exceptions include Santa Fe, which applies its tax only to residential property sales, and New York City, which levies higher tax rates on single-family residential transactions. Some jurisdictions apply lower tax rates or offer exemptions to certain transaction types, such as income-restricted affordable housing, properties newly converted to residential use, and first-time home purchases.[6]

- Where the revenue goes: In close to half of localities with progressive transfer taxes, the revenue provides a dedicated funding source for affordable housing and homelessness alleviation. In places such as Baltimore, Los Angeles, and Santa Fe, no dedicated funding for housing existed before the introduction of a progressive real estate transfer tax. Localities including Montgomery County and Santa Monica use the revenue to improve public school facilities, and New York City puts funding toward its transit system. In several localities, the tax acts as a general revenue source, bolstering resources for critical local responsibilities such as infrastructure, health, and parks.

Communities may not need to wait until high-end properties are sold to collect greater tax revenue from them. In addition to enacting progressive taxes on real estate transactions, some localities and states have considered levying graduated rates in the annual property tax. Increased property tax rates for high-end homes have been proposed in places including the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, New York, and Rhode Island.[7] A recent proposal in D.C., for example, would add a new marginal tax bracket on homes worth more than $2 million, affecting owners of the District’s most expensive 5 percent of residences.[8] The concept has international precedent in Ireland, Denmark, and Singapore.[9]

Closing wealth gaps, advancing equity: The case for local mansion taxes

Advancing economic and racial equity

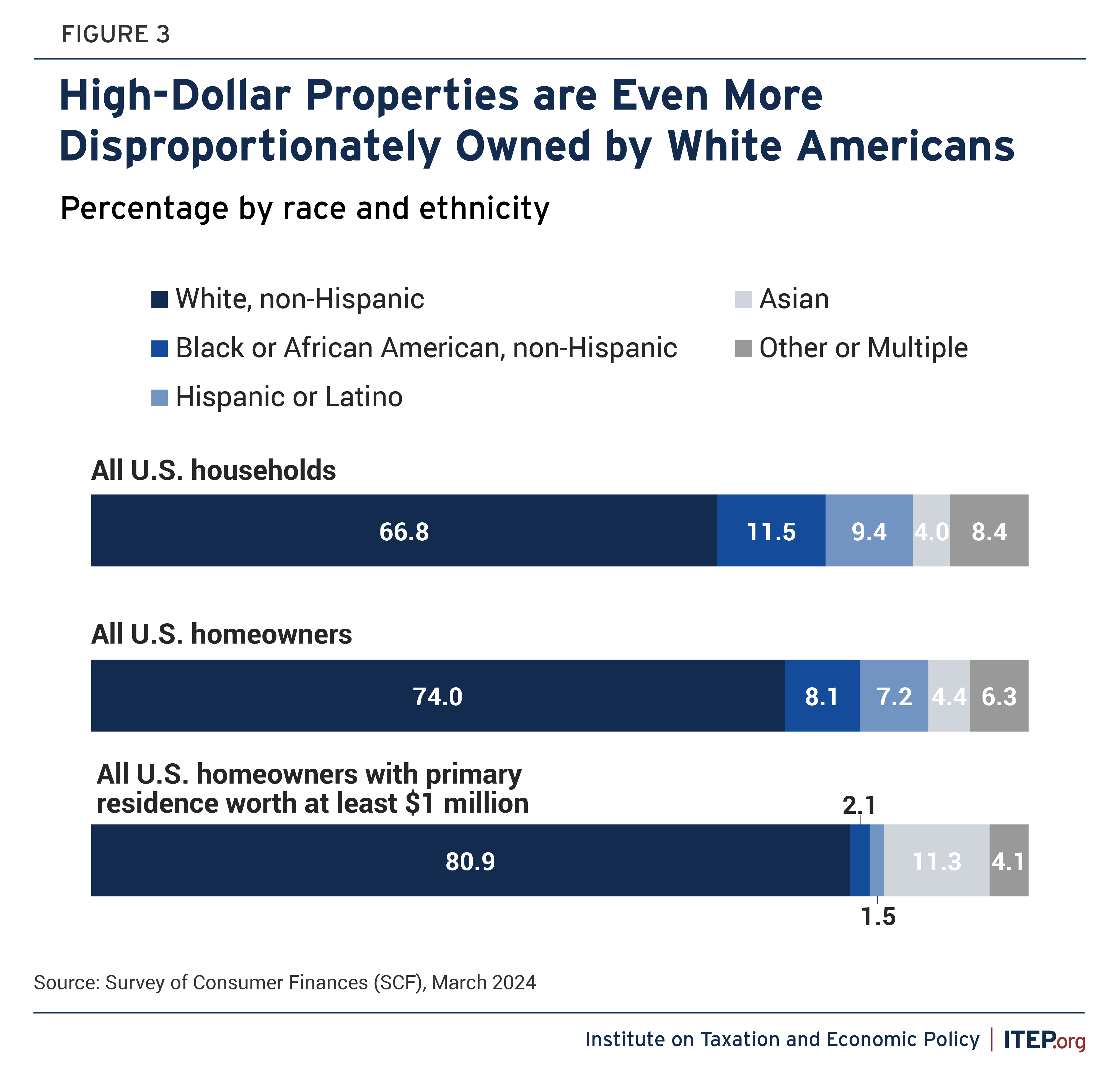

Taxes on high-end homes facilitate deeper investments in the common good by increasing contributions made by those at the top of the economic ladder. National evidence indicates that owners of the most valuable homes are higher-income and wealthier than the population at large. According to 2022 Federal Reserve data, for instance, households with primary homes worth at least $1 million have a median income five times larger than the median income of all U.S. households.[10] Owners of high-dollar properties are also disproportionately white, a reflection of historic and ongoing injustices that have conferred wealth-building advantages on white families while constraining homeownership and economic opportunity for Black Americans and other people of color.[11]

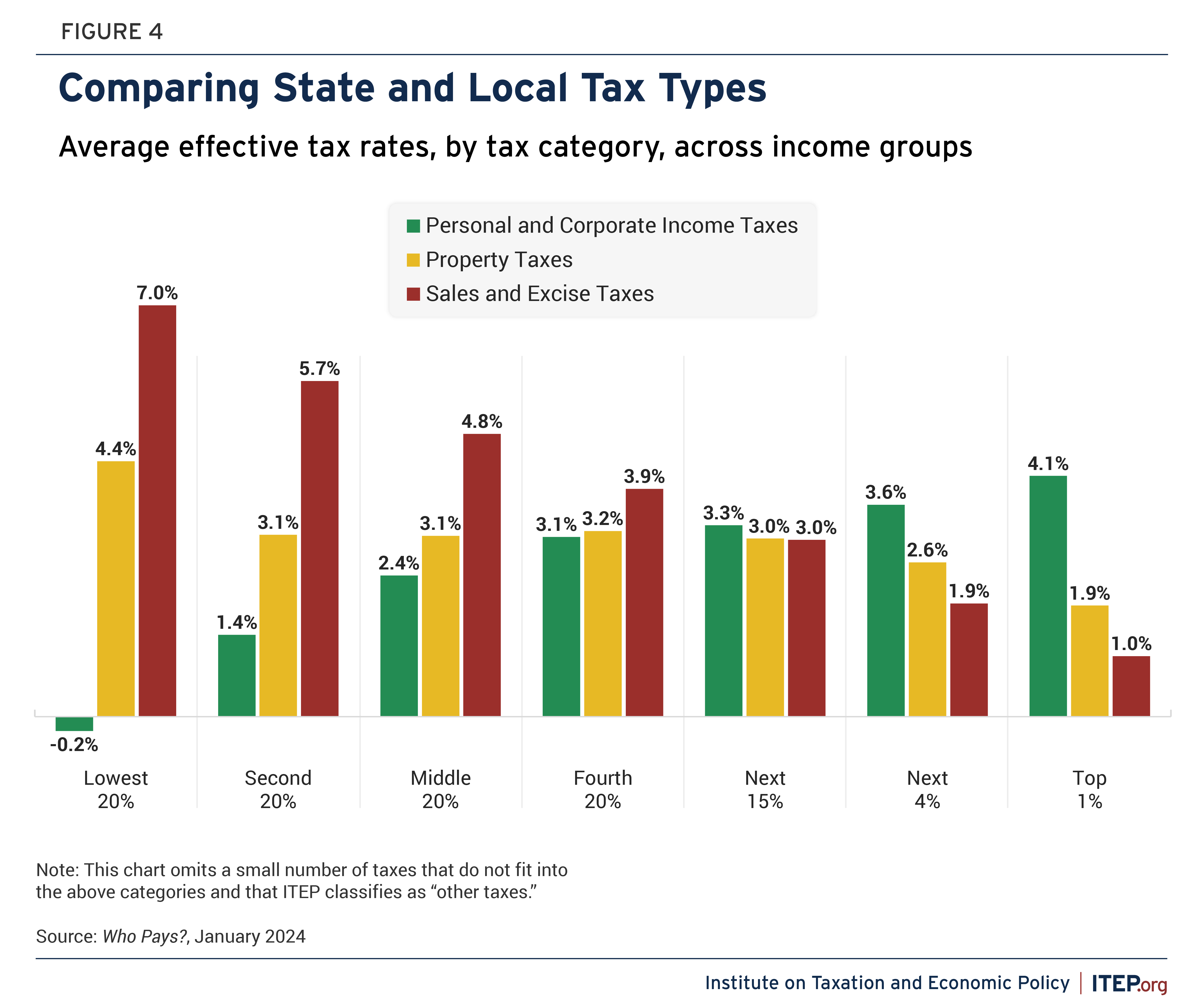

These disparities contrast sharply with the upside-down structure of many state and local government tax codes. ITEP’s Who Pays? finds the vast majority of Americans live in places with regressive tax systems which ask the least of residents with the greatest resources.[12] Annual flat-rate property taxes and consumption taxes, which together represent nearly nine in 10 tax dollars collected by localities nationwide, both tend to require households with lower and moderate incomes to pay higher effective tax rates than the wealthy.[13] Mansion taxes can advance tax fairness and help build revenue systems that are better equipped to keep up with community needs in an era of heightened wealth concentration.[14]

A practical and effective revenue source

Taxes on the sale of real estate and other property have been used by governments for centuries, and by U.S. local governments for over seven decades.[15] Today localities in two-thirds of states levy real estate transfer taxes, most commonly as a flat percentage of a property’s purchase price.[16] The longstanding role of these taxes in public budgets owes in no small part to their administrative practicality. Real estate transfer taxes have been found to be relatively cost-effective for local governments to implement, straightforward for citizens to understand, and difficult for taxpayers to dodge.[17] These practical strengths make real estate transfer taxes with progressive tax rate schedules an especially compelling option for localities seeking to fairly and efficiently bolster public investments.[18]

In many places, graduated real estate transfer taxes are also among the more straightforward progressive revenue sources for localities in light of state-imposed tax policy limits. Nearly all states enforce laws restricting local governments from raising new revenue through progressive reforms to the annual property tax.[19] Likewise, local income taxes are limited or banned by some states.[20] Real estate transfer taxes, in contrast, often face fewer constraints — although specifics vary from state to state.[21] Curbing counterproductive tax policy preemption and better equipping local governments to equitably raise adequate revenue is an essential aim for those seeking stronger and fairer communities.[22] At the same time, for localities in many states, levies on high-end real estate transactions offer an immediate way to begin making progress using tools presently at hand.

Local mansion taxes in action

In cities and counties across the U.S., progressive taxes on high-dollar real estate sales are unlocking critical new revenue used to build more resilient and inclusive communities. A deeper look at four localities — Baltimore, Berkeley, Evanston, and Santa Fe — sheds light on how these measures came to be adopted and how they are delivering results for places of differing population size, geography, and economic composition.

Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore introduced a tax on real estate sales above $1 million in 2018. Two years earlier, city voters approved the creation of a housing trust fund.[23] With no dedicated revenue source, however, the fund remained empty — until lawmakers enacted a 0.75 percent levy, called the Yield Tax, on residential and commercial property transactions worth more than $1 million.[24] The million-dollar threshold is approximately five times the median home value in Baltimore.[25]

Proceeds from the additional charge on expensive property sales, over $50 million to date, are deployed to build and preserve affordable houses and apartments for Baltimore residents with low incomes.[26] The Yield Tax is paid in addition to the city’s broader 2.5 percent transfer and recordation taxes collected on all real estate transactions, bringing the total top tax rate on high-end transactions to 3.25 percent.[27] Funding from the broad-based 2.5 percent recordation and transfer taxes support city operations including education, health, and infrastructure.

Berkeley, California

Berkeley voters established a graduated real estate transfer tax in 2018 to support community members experiencing or at risk of becoming unhoused. The progressive tax applies a levy of 2.5 percent on the full value of residential and commercial properties sold for more than $1.6 million.[28] Transactions below this amount are taxed at 1.5 percent. The threshold for the top tax rate is adjusted annually to track the city’s one-third most expensive property transactions.

The additional 1 percent levy on high-end transactions collects approximately $10 million per year, boosting Berkeley’s property transfer tax revenue by roughly 50 percent.[29] The funds are devoted to providing shelter and support to unhoused Berkeley residents. The revenue allows the city to better meet the needs of community members with temporary and long-term housing as well as services supporting health and hygiene, mental health, case management, outreach, and more.[30] It also enables the city to invest in legal aid and other interventions to support residents at risk of becoming homeless.[31]

Evanston, Illinois

Evanston voters approved the creation of a progressive property transfer tax in 2018.[32] Under a graduated three-tier structure, residential and commercial real estate sold for over $5 million is taxed at 0.9 percent, transactions between $1.5 million and $5 million are taxed at 0.7 percent, and properties worth $1.5 million or less are taxed at 0.5 percent.[33] The threshold for the top tax rate is approximately 10 times the median value of homes in the city.[34]

The stepped-up tax rates on real estate sales over $1.5 million result in approximately $700,000 in added annual revenue, increasing city transfer tax collections by around one fourth.[35] The proceeds support Evanston’s first-in-the-nation municipal reparations program, established to redress historic injustices faced by Black residents.[36] Initiatives funded by the tax include homeownership support and direct compensation for residents and descendants harmed by anti-Black policies and practices in the city’s past.[37] Revenue from the transfer tax also funds core municipal responsibilities such as public safety, health, parks and recreation, and infrastructure.

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Santa Fe voters established a progressive real estate transfer tax in 2023 to provide a permanent funding source for affordable housing.[38] Santa Fe’s 3 percent tax, expected to take effect May 2024, applies to the portion of single-family residential property sold for more than $1 million.[39] The marginal structure means a home sold for $1.1 million faces tax on $100,000 of its value, similar to the graduated design of the federal income tax. The million-dollar threshold is nearly three times the value of the median Santa Fe home.[40]

Proceeds from these high-end purchases will provide an estimated $6 million per year into Santa Fe’s affordable housing trust fund, approximately tripling the fund’s size.[41] The revenue will be used to build new homes and ease housing costs for low-income and middle-income residents.

Conclusion

A widening gap between the wealthiest and those struggling to make ends meet is evidenced in communities across the country, with recent data showing more American residents going unhoused, more households paying unaffordable amounts on rent, and home prices growing more out-of-proportion to a typical household’s earnings. To meet the demands of the moment, a growing number of cities and counties across the U.S. are using progressive taxes on expensive real estate transactions. As communities contend with today’s most pressing challenges, these taxes have proven a practical and effective way to fund public investments, advance equity, and achieve fairer local tax codes.

Endnotes

[1] ITEP review of local election results in California, Illinois, and New Mexico; sources include state and local election administrators and the California Local Government Finance Almanac.

[2] “Voting Info,” Bring Chicago Home, 2024. https://www.bringchicagohome.org/voting-info.

Emma Platoff and Matt Stout, “Overshadowed by Rent Control Debate, Proposals for Transfer Taxes Pick Up Steam in Housing Discussions,” Boston Globe, May 7, 2023. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2023/05/07/metro/overshadowed-by-rent-control-debate-proposals-transfer-taxes-pick-up-steam-housing-discussions/.

Joseph Irvin and Heather Stroud, “Report to City Council: Potential Revenue Ballot Measures and Expenditure Plans for Housing, Transit, and Snow Removal for the November 2024 Election,” City of South Lake Tahoe, September 26, 2023. https://legistarweb-production.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/attachment/pdf/2183501/01-Staff_Report_Potential_Revenue_Ballot_Measures_Nov._2024___9-26-2023.pdf.

Devan Patel, “Sunnyvale to Poll Voters if They’d Support an Additional Tax on Property Transfers,” Silicon Valley Business Journal, January 24, 2024. https://www.bizjournals.com/sanjose/news/2024/01/29/sunnyvale-property-transfer-tax-november-election.html.

Savana Dunning, “Is a ‘Mansion Tax’ right for Newport? Realtors raise concerns as home prices rise,’ The Newport Daily News, March 11, 2024. https://www.newportri.com/story/news/local/2024/03/11/newport-explores-tax-on-property-sales-over-2-million-gets-pushback/72897971007/.

[3] “Statistical Profile of the New York City Real Property Transfer Tax,” New York City Department of Finance, 2022. https://www.nyc.gov/site/finance/business/rptt-reports-statistical-profiles.page.

[4] ITEP analysis of local budgets and financial reports.

[5] ITEP review of local election results in California, Illinois, and New Mexico; sources include state and local election administrators and the California Local Government Finance Almanac.

[6] “Real Property Transfer Tax and Measure ULA FAQ,” Los Angeles Office of Finance. https://finance.lacity.gov/faq/measure-ula.

San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR), “San Francisco Prop C – Transfer Tax Waiver,” March 2024. https://www.spur.org/voter-guide/2024-03/sf-prop-c-transfer-tax-waiver.

“Real Estate Transfer Tax,” City of Oakland. https://www.oaklandca.gov/resources/real-estate-transfer-tax.

Shane Phillips and Maya Ofek, “How Will the Measure ULA Transfer Tax Initiative Impact Housing Production in Los Angeles?” UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, October 2022. https://lewis.ucla.edu/research/how-will-the-measure-ula-transfer-tax-initiative-impact-housing-production-in-los-angeles/.

[7] Andrew Boardman, Kamolika Das, and Marco Guzman, “Worthwhile Ideas for a Stronger and Fairer D.C. Tax Code,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 17, 2024. https://itep.org/worthwhile-ideas-for-a-stronger-fairer-washington-dc-tax-code/.

House Resolution No. 109, Hawaii House of Representatives, 2017. https://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessions/session2017/Bills/HR109_.pdf.

“Mendoza Proposes Higher Property Assessments on Pricey Homes,” The Real Deal, January 8, 2019.

https://therealdeal.com/chicago/2019/01/08/candidate-mendoza-proposes-higher-property-assessments-on-pricey-homes/.

“Raising Revenues: Options for the City of New York to Secure New Sources of Funding for Services,” Office of the New York City Comptroller, May 23, 2023. https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/raising-revenues/.

Edward Fitzpatrick, “What Does ‘Taylor Swift Tax’ Tell us about Raimondo?” Providence Journal, March 29, 2015. https://www.providencejournal.com/story/news/politics/government/2015/03/29/what-does-taylor-swift-tax/34874774007/.

[8] Eliana Golding, “DC Can Advance Racial Equity and Black Homeownership through the Property Tax,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October 2023. https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dc-can-advance-racial-equity-and-black-homeownership-through-the-property-tax/.

[9] “Local Property Tax,” Citizens Information Board. https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/money-and-tax/tax/housing-taxes-and-reliefs/local-property-tax/.

“Introduction to Property in Denmark,” Danish Customs and Tax Administration. https://skat.dk/en-us/individuals/property/introduction-to-property-in-denmark.

“Property Tax Rates,” Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore. https://www.iras.gov.sg/quick-links/tax-rates/property-tax-rates.

Bethany P. Paquin, “Chronicle of the 161-Year History of StateImposed Property Tax Limitations,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, April 2015. https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/paquin-wp15bp1.pdf.

[10] ITEP analysis of 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances, Federal Reserve. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm.

[11] Carl Davis and Meg Wiehe, “Taxes and Racial Equity: An Overview of State and Local Policy Impacts,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, March 31, 2021. https://itep.org/taxes-and-racial-equity/.

Dorothy Brown, “Homeownership in Black and White,” University of Memphis Law Review, 2018. https://www.memphis.edu/law/documents/brown_final.pdf.

[12] “Who Pays? 7th Edition,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 8, 2024. https://itep.org/whopays-7th-edition/.

[13] Andrew Boardman and Galen Hendricks, “How Local Governments Raise Revenue—and What it Means for Tax Equity,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, March 30, 2023. https://itep.org/how-local-governments-raise-revenue-effects-on-tax-equity/.

[14] Andrew D. Appleby, “Targeted Taxes: Localities Take Aim at Large Employers to Solve Homelessness and Transportation Challenges,” Oregon Law Review, May 14, 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3453869.

Roxanne Bland, “Soak the Rich! Part 2: The Mansion Tax,” Tax Notes, August 5, 2019. https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-state/property-taxation/soak-rich-part-2-mansion-tax/2019/08/05/29rb4.

[15] “The Intergovernmental Aspects of Documentary Taxes,” U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, September 1964. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1410/.

[16] 2021 Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances, U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2021/econ/local/public-use-datasets.html.

[17] Terri A. Sexton, “Taxing Property Transactions Versus Taxing Property Ownership,” in Challenging the Conventional Wisdom on the Property Tax, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2010. https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/challenging-the-conventional-wisdom-on-the-property-tax-chp-7.pdf.

[18]Andrew D. Appleby, “Targeted Taxes: Localities Take Aim at Large Employers to Solve Homelessness and Transportation Challenges,” Oregon Law Review, May 14, 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3453869.

[19] Bethany P. Paquin, “Chronicle of the 161-Year History of State-Imposed Property Tax Limitations,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, April 2015. https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/paquin-wp15bp1.pdf.

[20] Michael Pagano and Christopher Hoene, “City Budgets in an Era of Increased Uncertainty,” Brookings Institution, July 18, 2018. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/city-budgets-in-an-era-of-increased-uncertainty/.

Joel Griffith, Jonathan Harris, and Emilia Istrate, “Doing More with Less: State Revenue Limitations and Mandates on County Finances,” 2016. https://www.naco.org/resources/doing-more-less-state-revenue-limitations-and-mandates-county-finances.

[21] For example, five states do not allow property transfer taxes. For more information, see Michael Leachman and Samantha Waxman, “State ‘Mansion Taxes’ on Very Expensive Homes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 1, 2019. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-mansion-taxes-on-very-expensive-homes.

[22] Wesley Tharpe, “Easing State Restraints on Local Taxing Power Can Strengthen Democracy, Promote Prosperity and Equity,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 28, 2023. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/easing-state-restraints-on-local-taxing-power-can-strengthen.

[23] “Baltimore Supports Housing for All,” Housing Trust Fund Project – Community Change, 2017. https://housingtrustfundproject.org/baltimore-voters-supports-housing-for-all/.

[24] File No. 18-215, Recordation and Transfer Taxes – Surtax – Dedicating Surtax Proceeds to Affordable Housing Trust Fund, Baltimore City Council, 2018. https://baltimore.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=3479031&GUID=695EE6A1-C76B-44CA-98FF-9C13A2852B4F&Options=&Search=.

Adam Bednar, “Baltimore Affordable Housing Deal Signing Set for Wednesday,” The Daily Record, September 25, 2018. https://thedailyrecord.com/2018/09/25/baltimore-affordable-housing-deal-signing-set-for-wednesday/.

[25] American Community Survey 2018-2022 5-year estimates for the city of Baltimore, U.S. Census Bureau.

[26] “Affordable Housing Trust Fund Program and Revenue Update – May 23, 2023,” Baltimore City Department of Housing and Community Development, May 23, 2023. https://dhcd.baltimorecity.gov/sites/default/files/AHTF%20Program%20&Rev%20update%205.23.23-SE.pdf.

“Annual Expenditures for Affordable Rental Housing in Baltimore City,” Baltimore City Department of Housing and Community Development. https://dhcd.baltimorecity.gov/nd/affordable-housing-inventory.

[27] Article 28: Taxes, Baltimore Department of Legislative Reference. https://legislativereference.baltimorecity.gov/sites/default/files/Art%2028%20-%20Taxes%20(rev%2017OCT23).pdf.

[28] Chapter 7.52 – Real Property Transfer Tax, Berkeley Municipal Code. https://berkeley.municipal.codes/BMC/7.52.040.

[29] “Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for Fiscal Year 2023,” City of Berkeley. https://berkeleyca.gov/sites/default/files/documents/annual-comprehensive-financial-report-fy2023.pdf.

[30] “Measure P: Real Property Transfer Tax to Fund Homeless Services,” City of Berkeley. https://berkeleyca.gov/your-government/our-work/bond-revenue-measures/measure-p.

[31] Dee Williams-Ridley, “Measure P and Impact on Homeless Services in Berkeley,” City of Berkeley Office of the City Manager, April 25, 2023. https://berkeleyca.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2023-04-25%20Off%20Agenda%20Memo%20-%20Measure%20P%20and%20Impact%20on%20Homeless%20Services%20in%20Berkeley.pdf.

[32] Ordinance 148-O-18, City of Evanston, December 7, 2018. https://www.cityofevanston.org/home/showpublisheddocument/45934/636803129206370000.

[33] Chapter 25 – Real Estate Transfer Tax, Evanston Code of Ordinances. https://library.municode.com/il/evanston/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=TIT3BURE_CH25REESTRTA_3-25-2IMTA.

[34] American Community Survey 2018-2022 5-year estimates for the city of Evanston, U.S. Census Bureau.

[35] Tasheik Kerr, “Memorandum Designating a Percentage of the Real Estate Transfer Tax on the Sale of Property Over 1,500,00.01 to the Reparations Fund,” City of Evanston, November 3, 2022. https://cityofevanston.civicweb.net/document/88785/Designating%20a%20percentage%20of%20the%20Real%20Estate%20Tra.pdf?handle=E161254A0D6D42FCAFE03FB2046AE267.

[36] Saul Pink, “City Council Greenlights Annual $1 Million of Real Estate Transfer Tax Funds for Reparations,” The Daily Northwestern, November 15, 2022. https://dailynorthwestern.com/2022/11/15/city/city-council-greenlights-annual-1-million-of-real-estate-transfer-tax-funds-for-reparations/.

[37] “City Distributes Over $1 Million in Reparations Funding,” City of Evanston, August 16, 2023. https://www.cityofevanston.org/Home/Components/News/News/6062/17.

[38] Bill No. 2023-23, City of Santa Fe, 2023. https://santafenm.gov/High-end_Excise_Tax_for_Affordable_Housing_%28signed%29.pdf.

[39] Danielle Prokop, “Official 2023 Election Results are in, but Recounts Await for Close Calls in Some New Mexico Races,” Source NM, November 29, 2023. https://sourcenm.com/2023/11/29/official-2023-nm-election-results-are-in/.

[40] American Community Survey 2018-2022 5-year estimates for the city of Santa Fe, U.S. Census Bureau.

[41] Megan Myscofski, “Santa Fe Officials Say ‘Mansion Tax’ Would Provide Steady Funding for Affordable Housing,” KUNM, November 2, 2023. https://www.kunm.org/local-news/2023-11-02/santa-fe-mayor-and-affordable-housing-director-talk-about-the-mansion-tax.

“The Santa Fe Affordable Housing Trust Fund,” Santa Fe Housing Action. https://santafehousingaction.org/trust-fund/.