Today the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) released its final regulations cracking down on a tax shelter long favored by private and religious K-12 schools, and more recently adopted by some “blue state” lawmakers in the wake of the 2017 Trump tax cut.

The regulations come more than a year after the IRS first announced the launch of this project and about nine months after it unveiled an initial draft. Overall, the regulations are a big improvement but fall short of ending the tax shelter entirely for wealthy investors. The IRS has indicated that additional guidance will be needed to deal with a variety of lingering issues, though it remains to be seen what that guidance will entail.

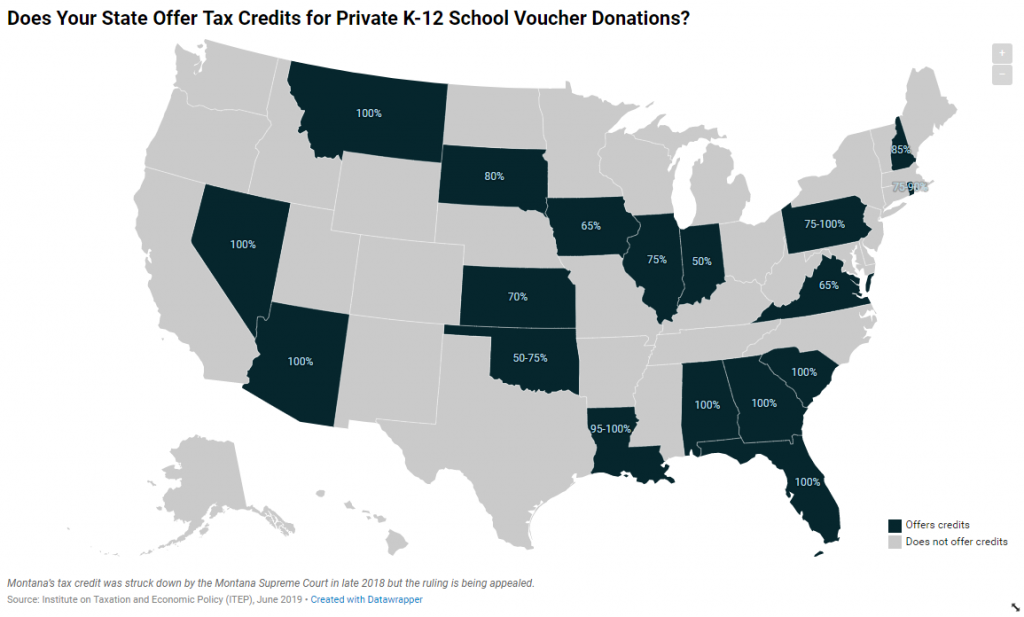

At issue are state and local tax credits for taxpayers who make so-called “charitable donations” to specific causes cherry-picked by elected officials, including private K-12 schooling. For years, private school donors have used tax credits in exchange for donating to school voucher programs to beef up their federal charitable write-offs at little or no cost to themselves, since up to 100 percent of their “charitable gifts” to such funds are reimbursed with state tax credits (18 states offer these types of credits). A large state tax credit for private school donations combined with the federal tax deduction for charitable contributions allowed some high-income taxpayers to receive a tax benefit larger than their actual donation. In essence, state and federal law incentivized donations to private schools through a system of credits and deductions that allowed high-income taxpayers to profit from so-called donations.

For years, these perverse tax shelters went unchallenged. But then in 2017 federal lawmakers enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which capped the federal income tax deduction for state and local taxes (SALT) at $10,000. Lawmakers in higher-income states, which have a greater number of taxpayers affected by the SALT cap, began to take interest in this shelter as a way of helping their residents cut their federal tax bills. If federal law no longer allows SALT payments above $10,000 to be deducted, why not allow taxpayers to make “charitable gifts” (reimbursed with tax credits) to their state or local government instead of tax payments? New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Oregon enacted these arrangements. Then the IRS noticed the surge of interest in this tax strategy and decided to get involved.

Under the new regulations, people receiving state tax credits in return for donations will have to subtract those credits when determining the real, deductible amount that they donated. For example, if a taxpayer donates $100 to support private or public education in Pennsylvania but receives a $90 tax credit in return, then only $10 of their donation will be deemed truly charitable and eligible for the federal charitable deduction. In other words, the regulations inject a welcome bit of common sense into the federal tax code’s definition of “charity.”

Some private school groups were up in arms about this proposal when it was first unveiled and argued that this change should only be implemented in the context of donations to public schools, not private ones. But the IRS wisely rejected that argument and will treat donations to all types of entities in the same way. Failing to do so would have created a grave inequity in our tax code, would have been unnecessarily complex and would have reopened the door to more creative SALT cap workaround schemes.

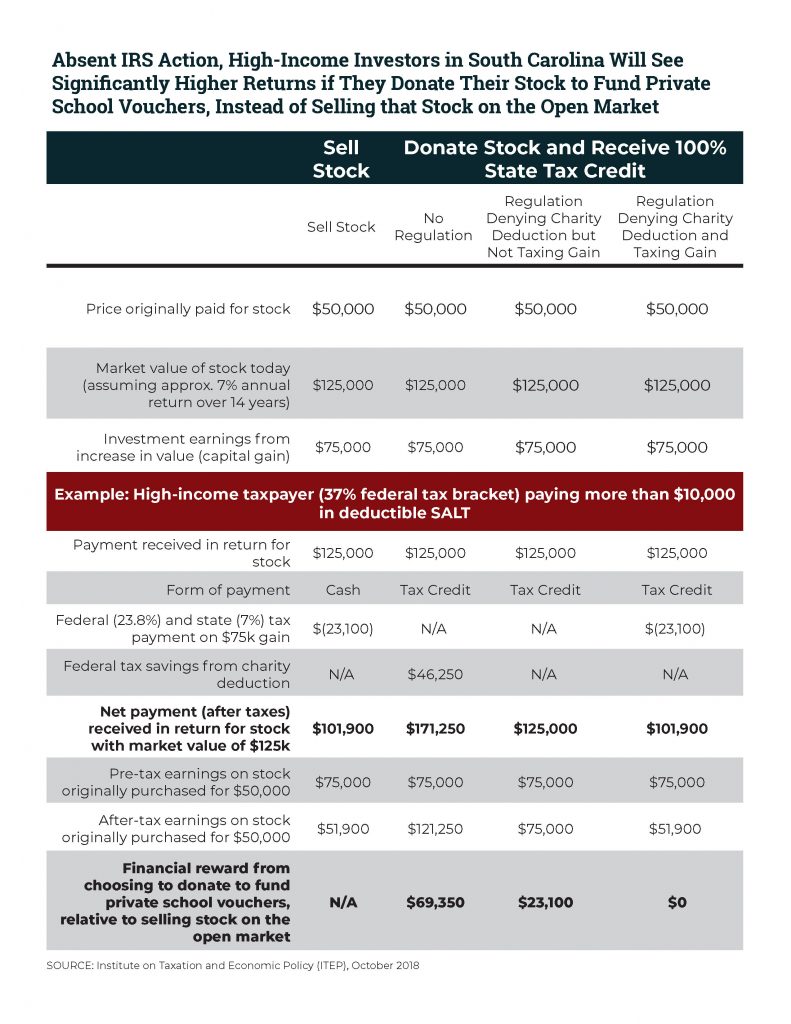

The main area where the regulations fall short, however, is in their treatment of investors donating stock or other property in exchange for tax credits. As ITEP explained in its comments on the initial draft of these regulations, investors in states such as South Carolina with stock they wish to offload will be advised by their accountants to “give” their stock away in return for a 100 percent tax credit, rather than sell that stock on the open market. To the IRS, selling a stock generates cash income that triggers a taxable capital gain, but a state tax credit received in return for donating stock has typically remained invisible. A South Carolina taxpayer with $75,000 in capital gains income, for example, could come out ahead by about $23,100 if they take their payment in the form of a state tax credit rather than cash, as ITEP has shown. In other words, some investors making so-called “charitable gifts” will continue to turn a profit as a perverse reward for sham generosity.

Without question, Congress could fix this lingering problem if it wished. Legislation introduced by Rep. Terri Sewell (D-AL) in the previous Congress, for instance, would require taxpayers to pay capital gains tax if they receive a large state tax credit as compensation for their gift of stock or property to a private school voucher organization. This improvement to our tax code’s measurement of real “charity” is worthwhile and could even be expanded to cover contributions of appreciated property to any organization.

But the IRS has also indicated that it might seek to address this problem on its own, as it mentions that additional guidance will be needed on a number of issues including the portion of federal law governing treatment of capital gains income.

Regardless of whether Congress or the IRS is the body to ultimately take action, it’s clear that additional work is needed to preserve the integrity of the charitable deduction by reserving it for real acts of charity, not sophisticated tax planning. Today’s regulation is a great step in that direction, but it shouldn’t be the final word.