A recently released working paper from Kimberly Clausing of Reed College finds that U.S. corporations will likely avoid taxes on nearly $300 billion in offshore profits every year for the foreseeable future.

The paper provides an informative new look into the level of offshore tax avoidance before and after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). While advocates of the TCJA claimed the tax law would end tax haven abuse through lowering the statutory rate and other measures, Clausing’s analysis shows that the TCJA will still allow the vast majority of offshore tax avoidance to remain intact.

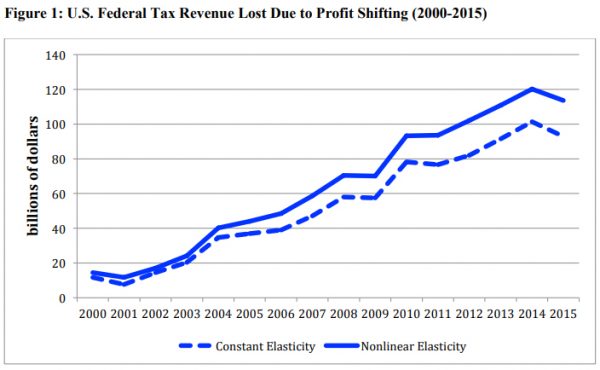

Clausing’s new report builds on previous reports showing the growth of offshore tax avoidance. Using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the paper reveals how revenue losses from profit shifting grew by leaps and bounds from just under $20 billion in 2000 to nearly $120 billion in 2015. The tremendous growth in the revenue loss demonstrates how multinationals have increasingly taken advantage of weaknesses in the U.S. and international tax systems to avoid taxes.

Looking forward, the paper breaks new ground by estimating the impact of lowering the U.S. statutory rate from 35 percent to 21 percent and implementing TCJA’s minimum tax on global low tax intangible income (GILTI). Clausing’s economic analysis finds that the tax on GILTI and the lower statutory rate will increase the U.S. tax base by $101.3 billion ($95.9 billion in 2015 dollars) through a reduction in offshore profit shifting. Applying this to the $400.2 billion ($379 billion in 2015 dollars) in estimated profits being shifted, the paper implies that even with the GILTI tax and lower rate in effect, companies will still shift $298.9 billion of income out of the United States each year. If you assume companies would owe a 20 percent U.S. effective tax rate (a huge drop from Clausing’s previous assumption of 30 percent) on this income had it not been shifted, it means that under the new system companies will avoid $59.8 billion in taxes on their offshore earnings each year.

It is worth noting that the paper likely overestimates the effectiveness of the TCJA in preventing tax avoidance by not including the effect of the new dividend exemption system. Allowing companies to repatriate their offshore earnings without any additional U.S. taxes is estimated under the bill to lose $223 billion over the next decade and likely will substantially increase offshore profit shifting. The exclusion of the dividend exemption is offset in part by the exclusion of the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT), which will reduce companies’ ability to shift profits. Even so, the net impact of including both provisions would still likely increase the amount of profit shifting considering that the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that the BEAT raises substantially less than the dividend exemption loses.

Overall, Clausing’s estimates are in line with the findings of an earlier analysis from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which estimated that pre-TCJA, corporations shifted about $300 billion in profits each year and that the post-TCJA amount is expected to be about $235 billion each year.

While both studies predict a modest reduction in profit shifting, it is critical to note that the JCT found that overall the international provisions (excluding the one-time revenue from the repatriation tax break) would lose about $14 billion. The most likely explanation for the disconnect is that some revenue being gained from reducing international tax avoidance is simply being given back to U.S. multinationals in the form of new tax breaks such as the break for foreign derived intangible income (FDII).

One additional notable finding of Clausing’s paper is its analysis comparing the efficacy of applying the GILTI tax on a global basis versus a per-country basis. Whether a tax on offshore profits is applied globally or on a per-country basis depends on how the foreign tax credit is applied. This credit prevents double taxation by allowing a corporation to subtract whatever it paid in taxes to other governments from its U.S. tax liability. TCJA continues the policy allowing companies to use foreign tax credits on a global basis, meaning they can reduce their U.S. taxes by combining foreign tax credits from both high- and low-tax jurisdictions. In contrast, a per-country approach would only allow a company to use foreign tax credits earned in each country to reduce its potential U.S. tax liability for earnings in that country. According to Clausing’s analysis, applying the GILTI tax on a per-country basis would increase the tax base by $113.5 billion ($107.5 in 2015 dollars) or more than 2.5 times the amount of the GILTI tax when applied globally.

Clausing’s finding reinforces the case for a per-country minimum tax like the one recently proposed by Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-OR) in the aptly named Per-Country Minimum Act. In fact, the increase in the U.S. tax base indicates that the bill’s application of a per-country limit could raise about $13.9 billion in one year or about $159 billion over 10 years.

More generally, Clausing’s report shows that the problem of offshore tax avoidance will continue to loom large following the passage of the TCJA. Rather than fixing the international system, the TCJA only scratched the surface in terms of shutting down tax avoidance. What is needed going forward to end this avoidance once and for all is a comprehensive reform that would end the incentive for companies to shift profits offshore. This would mean ensuring that offshore profits are not taxed more lightly than domestic profits, whether through exclusions, lower rates, inversions or other gimmicks that favor offshore investment over domestic investment. It also means requiring companies to publicly disclose basic financial information on a country-by-country basis, which would allow lawmakers and the public to judge whether companies are paying their fair share in taxes.