Key Findings

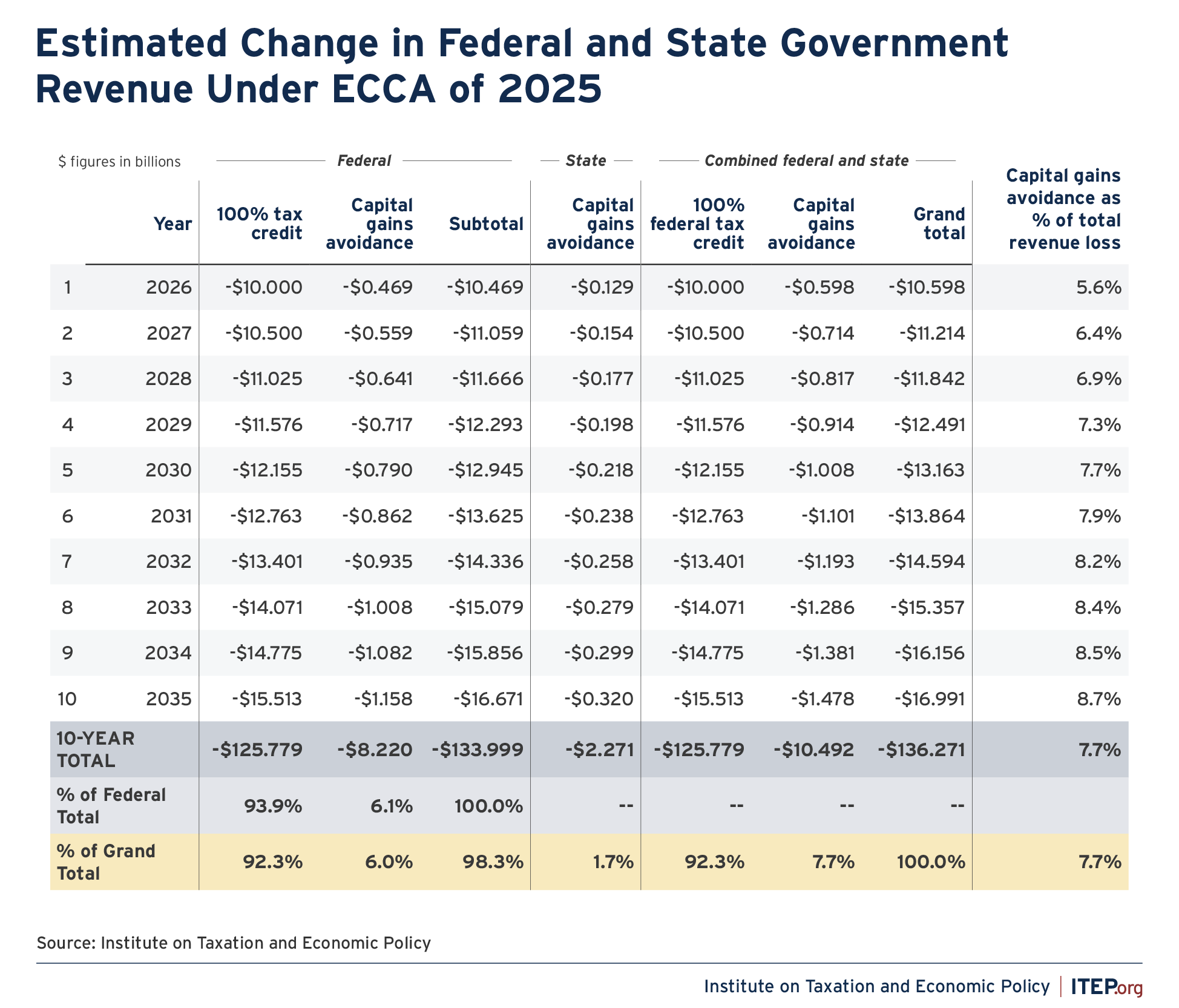

- The Educational Choice for Children Act of 2025 (ECCA) would provide donors to nonprofit groups that distribute private K-12 school vouchers with a dollar-for-dollar federal tax credit in exchange for their contributions. We estimate that these credits would reduce federal tax revenues by $10 billion in 2026 and by $125.8 billion over the next 10 years.

- In addition to the federal government covering the full cost of these donations with tax credits, donors would also be able to reduce their taxes further by avoiding capital gains tax on contributions of appreciated stock. We estimate that this form of tax avoidance would reduce federal revenues by an additional $469 million in 2026 and by $8.2 billion over the next 10 years. It would also reduce state revenues by $129 million in 2026 and by $2.3 billion over the next 10 years. In total, capital gains tax avoidance would come at a combined cost to federal and state governments of $598 million in 2026 and $10.5 billion over 10 years.

- In total, the ECCA would reduce federal and state tax revenues by $10.6 billion in 2026 and by $136.3 billion over the next 10 years. Federal tax revenues would decline by $134 billion over 10 years while state revenues would decline by $2.3 billion.

Overview of the Tax Provisions in the ECCA

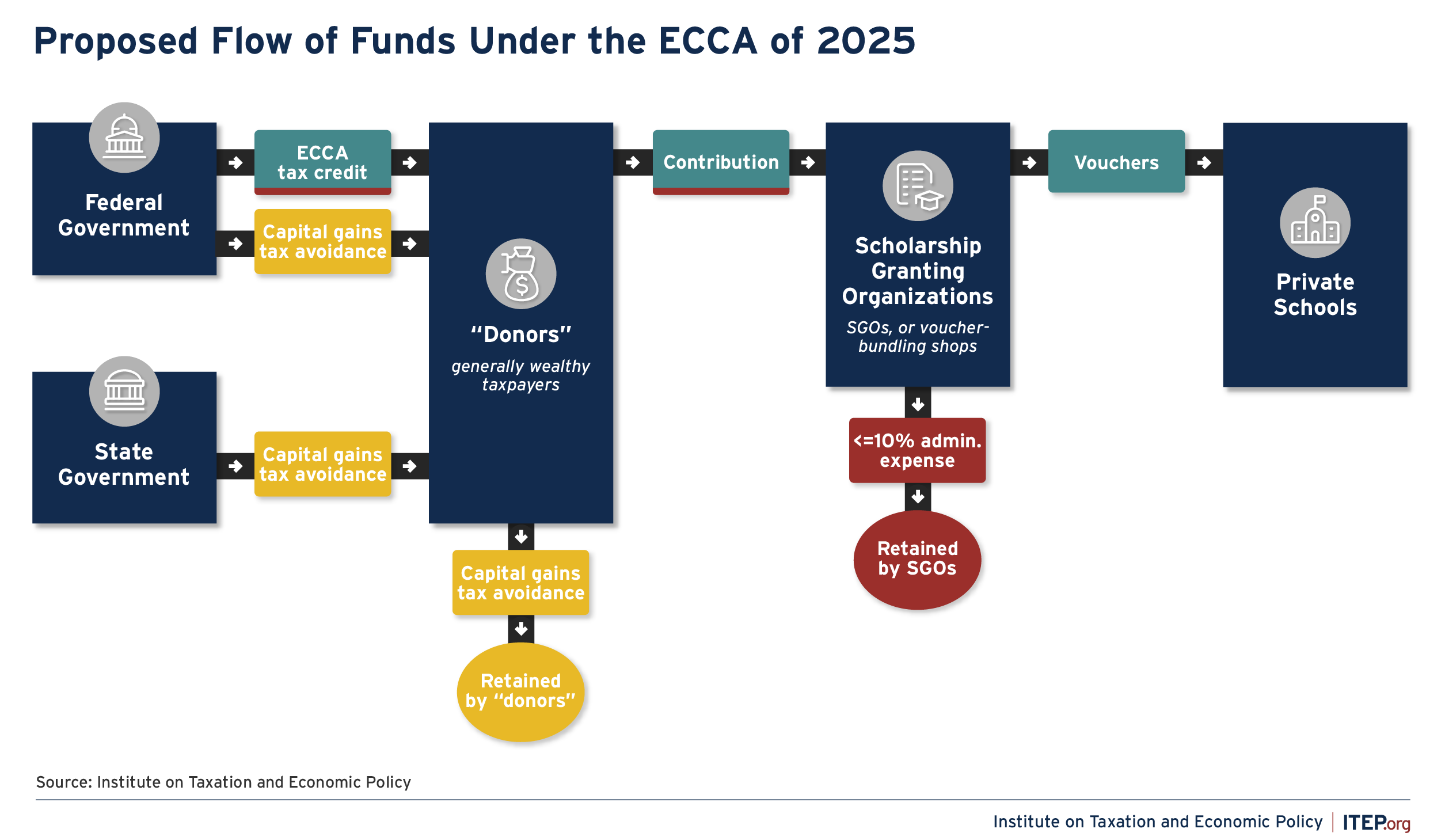

The Education Choice for Children Act of 2025 (ECCA) has been introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives as H.R. 833 and in the U.S. Senate as S. 292. The bill proposes a 100 percent tax credit—that is, a full reimbursement—for individual and corporate contributions to nonprofits known as Scholarship Granting Organizations (SGOs). These SGOs are tasked with bundling the donations and converting them, primarily, into vouchers for free or reduced tuition at private K-12 schools.[1] An overview of the flow of funds envisioned by the bill is provided in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

The tax credits allowed under the bill would be nonrefundable, meaning they could not exceed the taxpayer’s federal income tax liability. Credits claimed by individuals could, however, be carried forward up to five years for use against future tax liability.

Individual claimants’ tax credits could not exceed the greater of $5,000 or 10 percent of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). In practice, the 10 percent limitation is likely to be the far more relevant of the two limits because, as described below, there is good reason to expect that most contributors would have high incomes. For corporate claimants, the tax credits claimed could not exceed 5 percent of taxable income.

For individuals, ECCA tax credits could not be claimed in combination with the federal charitable deduction allowed under 26 U.S. Code § 170. Allowing taxpayers to claim a charitable deduction and 100 percent credit on the same donation would result in tax cuts larger than the amount contributed. This was a problem for many years in the context of state-level tax credits analogous to those contained in ECCA. The IRS addressed this issue in 2019 by issuing regulations eliminating or prorating federal charitable deductions in cases where the contributions benefiting from those deductions also benefited from large state or local tax credits.[2]

The aggregate amount of credits distributed under ECCA could not exceed $10 billion in its first year. That cap would then be increased by 5 percent per year, as long as at least 90 percent of available credits were claimed in the previous year. For reasons explained below, we expect that the full allotment of credits would be claimed each year and that this automatic escalator provision would be repeatedly triggered.

Available tax credits would be rationed on a first-come, first-served basis, with contributors receiving credits in the order in which their contributions were made. Ninety percent of the credits would be broadly available to tax filers throughout the country while the other 10 percent would be divided equally across the 50 states, plus the District of Columbia, and reserved for individuals residing in those states or for corporations created or organized in those states.

Contributions eligible for these tax credits could take the form of either cash or marketable securities such as corporate stock. The tax benefits of contributing marketable securities would be much larger than the benefits of contributing cash and, as explained below, we therefore expect virtually all contributions would be in the form of marketable securities.

Capital Gains Tax Implications

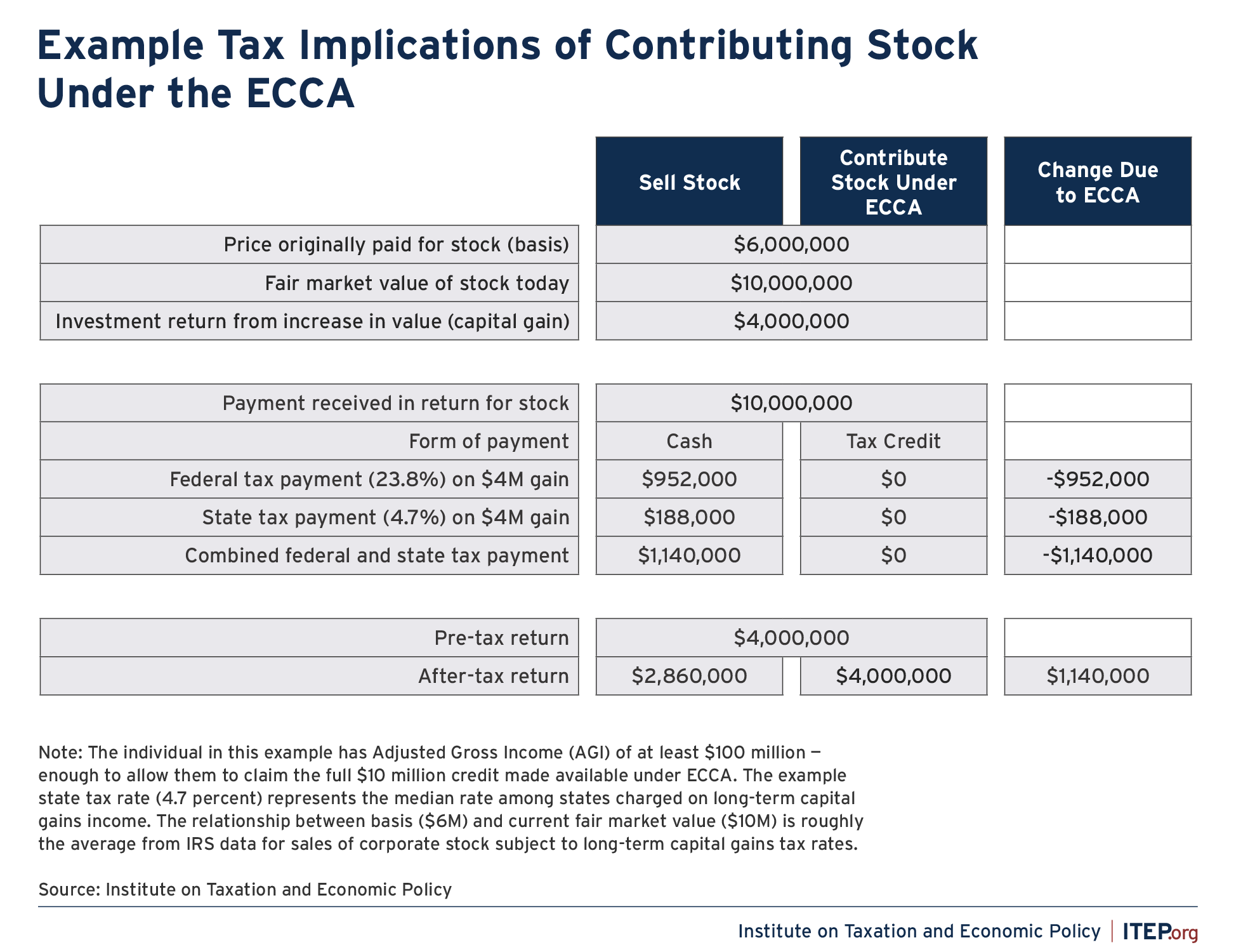

Figure 2 demonstrates the tax implications of contributing appreciated stock in exchange for ECCA tax credits compared to selling that stock to a buyer in the market. In this example, an individual who initially purchased stock for $6 million has seen it grow in value to $10 million, resulting in $4 million in unrealized income. If this stock has been held for at least one year, this $4 million return would ordinarily be considered long-term capital gains and subject to a federal tax rate of 23.8 percent upon sale, resulting in a federal tax bill of $952,000. State taxes would add another $188,000 to that total, assuming the median long-term capital gains tax rate among states of 4.7 percent.[3] The total tax bill on this sale would therefore be $1.14 million.

Under the ECCA, a taxpayer in this situation would likely be advised by their accountant to forgo selling this stock in favor of contributing it to an SGO instead. If the taxpayer has at least $100 million in AGI, they would be eligible to claim an ECCA tax credit worth the full $10 million of their stock’s value—that is, 10 percent of their AGI. Doing so would result in the same pre-tax return as selling the stock (receipt of a $10 million tax credit rather than a $10 million cash payout). But it would not incur the $1.14 million income tax bill described above and depicted in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2

The disparate treatment of donated versus sold stock depicted in Figure 2 presents what can be described as a “tax shelter” opportunity. That is, it is likely to attract not just contributors who care deeply about funding private school vouchers through SGOs, but also contributors who will participate solely for the tax savings.[4]

It bears noting that the relevant aspects of ECCA’s mechanics have been confirmed by Robert Harvey, Deputy Chief of Staff for Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation. Specifically, Mr. Harvey responded to questioning from members of the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee about the same general kind of maneuver presented in Figure 2 by saying “there’s no capital gains tax” on stock contributed under ECCA.[5]

Some private schools and financial advisors are already advertising state-level credits similar to those in ECCA as tools for avoiding tax on capital gains.[6] The House Ways and Means Committee was afforded an opportunity to strip this tax shelter from a previous version of ECCA with an amendment proposed by Rep. Mike Thompson, but it ultimately voted that amendment down along party lines, with Republicans in opposition.[7]

Business Tax Implications

ECCA includes different guardrails for credits claimed by individuals versus corporations. Those differences could produce varying tax avoidance opportunities for different business types.

Individuals and non-corporate business owners, for instance, are explicitly barred from stacking federal and state tax credits on the same donation. That is, the federal credit must be reduced by the amount of any state tax credit received to avoid the combined credit amount exceeding the amount donated. This credit reduction requirement does not appear to apply to corporate claimants, however, and absent action by states or the IRS to bar stacking federal and state credits, some corporations may try to combine these tax benefits.

Corporate credit claimants face stricter guardrails in a different respect, however, as they are prevented from pairing any kind of federal tax deduction with ECCA credits. For individuals, that limitation is narrower and only applies to claiming ECCA credits in combination with charitable contribution deductions under 26 U.S. Code § 170. The bill language is ambiguous as to whether non-corporate business owners can claim ECCA credits in combination with business expense deductions allowed under 26 U.S. Code § 162. This is a common tax avoidance strategy used under state tax credits analogous to those in the ECCA, and it is possible that some business owners—particularly those with more aggressive accountants—may attempt to claim a federal business expense deduction and a federal ECCA tax credit on the same dollar of donation.[8]

The business tax avoidance opportunities just described could affect the revenue loss associated with ECCA, though we do not analyze these effects as we expect that the predominant use of the limited pool of available credits would be avoidance of capital gains tax on appreciated stock.

Federal Revenue Estimation

Our analysis of the tax revenue implications of ECCA begins from the observation that wealthy individuals holding appreciated stock would have the greatest financial incentive to contribute and are likely to receive the financial advice needed to be aware of the tax shelter opportunity embedded in this legislation.

Experience has shown that tax avoidance opportunities of the type contained in ECCA attract significant interest. In 2018, for example, a change in federal law ramped up the profitability of a tax shelter facilitated by a voucher tax credit in Arizona. Afterwards, taxpayers who had previously taken six months to claim the full allotment of state tax credits rushed to do so in just two minutes.[9]

ECCA contains a similar “first-come, first-served” application process to ration what is sure to be a highly sought-after tax shelter. Given the magnitude of the tax savings and ease of access, we expect that this tax shelter opportunity would be the primary driver of donor interest in this program and that virtually all tax credits made available under the bill would be quickly claimed by wealthy individuals contributing marketable securities to SGOs.

Individuals looking to dispose of corporate stock are well positioned to quickly exhaust the full $10 billion tax credit allotment that would be made available under ECCA. Our analysis of IRS and Congressional Budget Office (CBO) data suggests that more than $600 billion of corporate stock subject to long-term capital gains tax will be sold in 2026, with more than $50 billion of that occurring in the month of January.[10] Much of that sales volume will be attributable to high-income families, as evidenced by the fact that roughly two-thirds of net capital gains income flows to households with income over $1 million per year.[11]

Some taxpayers, however, are likely to use ECCA as a chance to increase their basis in highly appreciated positions that they do not intend to sell. Under this tax minimization strategy, taxpayers would give their stock to SGOs and rebuy the same amount of stock on the same day. The effect of this maneuver would be to leave their portfolio unchanged, but to swap out low-basis shares (reimbursed by the federal government with ECCA credits) with newly purchased, high-basis shares. While 26 U.S. Code § 1091 prevents this kind of gamesmanship in the context of losses, there is no equivalent statute or regulation preventing it in the context of gains.

ITEP and other organizations have been urging the IRS to address these kinds of problems, which currently arise under some state tax credit programs, by requiring recognition of gain when property is exchanged for large tax credits.[12] The IRS has not acted on that advice, though it has indicated that it thinks there is a problem.[13] Future regulatory action on this question could be made more difficult, however, by the fact that the House Ways and Means Committee implicitly endorsed the tax shelter when it chose to vote down the technical correction proposed by Rep. Mike Thompson.[14]

Given our expectation that capital gains tax avoidance will drive full take-up of the credits contained in ECCA, analyzing the quantity of tax credits claimed each year is a straightforward exercise. The bill starts with a $10 billion credit allotment in the first year, 2026, which is then increased by 5 percent each year as long as at least 90 percent of available credits were claimed in the prior year. Annual 5 percent increases would result in credit payouts of $15.513 billion by 2035, with $125.779 billion in total credits paid over the first 10 years the ECCA is in effect.

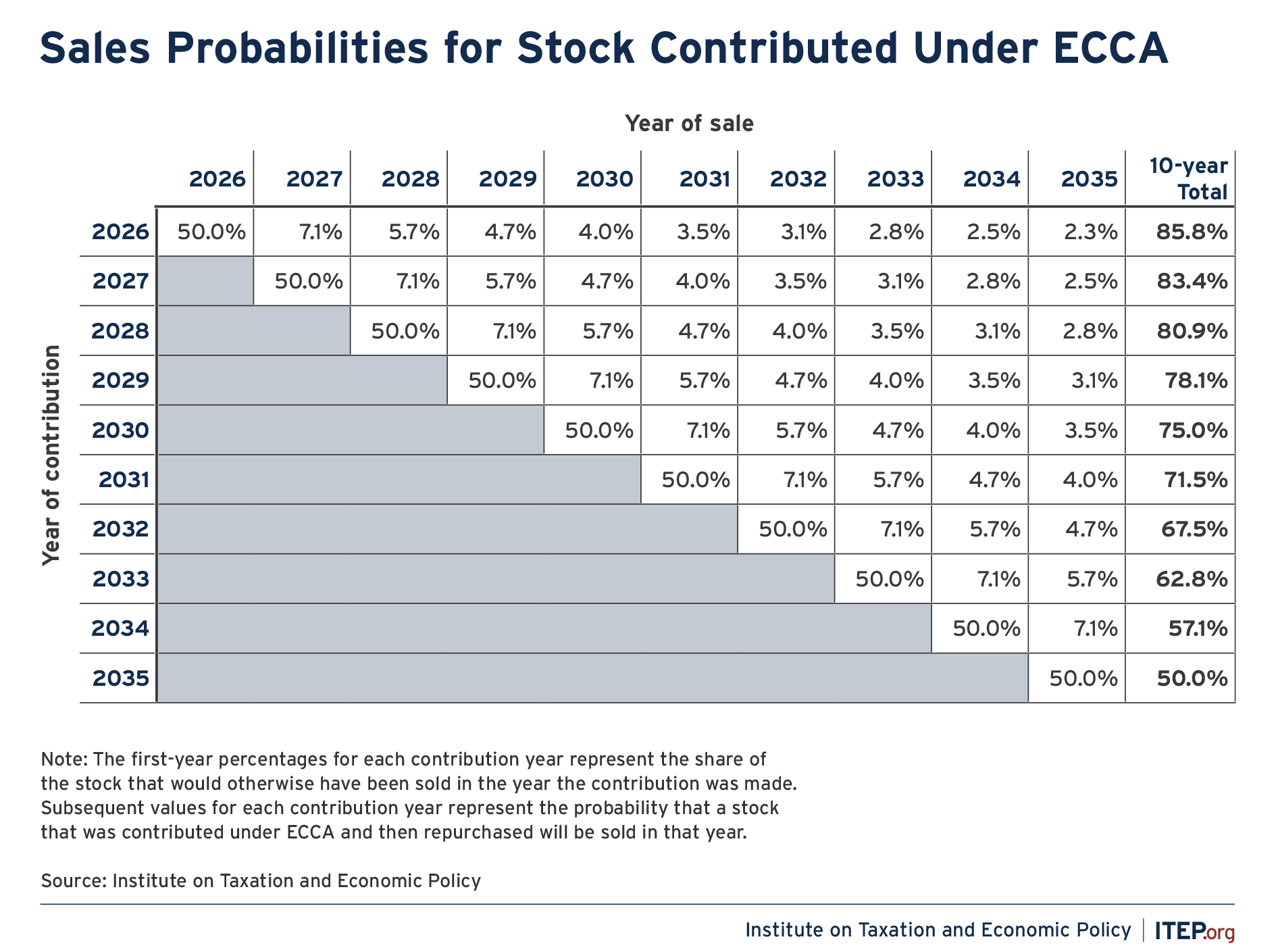

Determining the capital gains tax implications of corporate stock contributions is more complex and requires disaggregating the amount of securities donated (e.g., $10 billion in the first year) across two dimensions. First, we disaggregate across securities that would have been sold in the same year they were contributed versus a later year. And second, we disaggregate each sale into the portion representing basis versus appreciation.

As discussed above, the volume of corporate stock sales anticipated for the month of January 2026 would exceed the allotment of credits available under ECCA by a factor of five. Corporate stock sales throughout the entirety of 2026 are likely to exceed the available ECCA credits by a factor of more than 60. It is therefore possible that all ECCA credits could be claimed on contributions of stock that would have otherwise been sold in the same year that the contribution was made.

In practice, however, the first-come, first-served nature of the program would introduce a degree of unpredictability into the claims process where at least some highly motivated individuals would receive credits in return for contributions of stock they are not ready to part with, and who would choose to rebuy that stock at a higher basis. In light of this, we assume that the total value of stock contributed under the ECCA in any given year would be evenly divided between stock that would have been sold in the same year and stock that would have been sold in a later year.[15] We also assume that all contributed stock would have been subject to long-term capital gains tax rates rather than the higher, short-term rates, because the investing strategies that generate the latter type of gains are more timing-dependent and thus such contributions are less easily shifted into the narrow window of time in which we expect that ECCA credits will be available to claimants.

For stock that the taxpayer repurchased because they did not intend to sell it in the year the contribution was made, we estimate—for each year in the 10-year budget window—the probability that the repurchased shares will be sold in that year. To accomplish this, we use IRS data on the distribution of total sales price for long-term capital gains transactions of corporate stock, by length of time held, to estimate a logarithmic function representing the cumulative share of sales price by holding period.[16] Probabilities are then obtained from that function by starting from the median holding period (3.4 years) and examining the share of cumulative sales occurring between one and two years later (holding period of 4.4 to 5.4 years), between three and four years later (holding period of 5.4 to 6.4 years), and so on.

The result of this work is presented in Figure 3. In 2026, for example, 50 percent of all ECCA contributions are stock that would otherwise have been sold in 2026, 7.1 percent are stock that the taxpayer has rebought and will sell in 2027, 5.7 percent are rebought stock that will be sold in 2028, and so on. In total, 85.8 percent of stock contributed under ECCA in 2026 would otherwise have been sold sometime in the 10-year budget window.

FIGURE 3

The next step in our calculations requires disaggregating ECCA contributions into the basis and appreciation portions. To do this, we use IRS data on basis and gains for appreciated corporate stock sales subject to long-term capital gains tax rates and find that, on average, 44.3 percent of the sales price is comprised of appreciation with the other 55.7 percent representing basis. We use this 44.3 percent figure to isolate the portion of ECCA contributions comprised of asset appreciation that would otherwise have been subject to income tax. We expect that this approach errs on the side of underestimating the revenue loss associated with ECCA as owners of highly-appreciated stock would face the largest financial incentive to contribute under ECCA and one can therefore reasonably expect that ECCA contributions would be more tilted toward highly-appreciated assets than the average corporate stock sale.

The final component of the federal revenue calculation is the tax rate that would have applied to the asset appreciation in the absence of ECCA. The top federal tax rate on long-term capital gains is 23.8 percent, considering both the individual income tax and Net Investment Income Tax. The high-income people that we expect are most likely to contribute under ECCA would typically face this 23.8 percent rate, but in the interest of conservative estimation we use the slightly lower, 21.2 percent average marginal rate that applies to long-term capital gains overall, as estimated by CBO.[17]

With the values described above in hand, we calculate the federal capital gains tax implications of ECCA as follows. For the $10 billion of contributions made in 2026, for instance, 44.3 percent (or $4.43 billion) is comprised of asset appreciation that would otherwise have been subject to long-term capital gains tax at some point in time. Half of that (or $2.22 billion) would have been taxed at a 21.2 percent rate in 2026, 7.1 percent (or $315 million) would have been taxed in 2027, and so on. The calculations proceed in the same fashion for each contribution year and compound over time such that by 2035, for instance, the revenue loss is driven by a combination of contributions to SGOs made in every year between 2026 and 2035. In total, we estimate that ECCA would remove $38.8 billion in long-term capital gains from the federal definition of income over the next 10 years, at a cost to federal coffers of $8.2 billion.

State Revenue Estimation

Forty-one states and the District of Columbia levy individual income taxes. These taxes generally conform to the federal definition of capital gains income and, absent specific legislative or administrative action on the part of states, it is unlikely that they would automatically begin to treat receipt of a federal ECCA tax credit as a realization event subject to tax.

Our state-level estimates therefore start from our finding that ECCA would remove $38.8 billion from the federal definition of income over the next decade, including $2.2 billion in 2026 and $5.5 billion in 2035. Because high-income investors are likely to comprise nearly all of the donor base under ECCA, we allocate these income reductions across states in proportion to each state’s share of realized net capital gains income received by tax filers with AGI in excess of $1 million between 2018 and 2022 (the five most recent years with data as of this writing).[18] To determine the revenue loss associated with this reduction in capital gains income, we then apply each state’s effective top tax rate on long-term capital gains income, taking into account tax preferences for capital gains and deductions for federal income taxes paid.

Our state-level revenue estimates are reported at the aggregate, nationwide level in Figure 4 alongside federal revenue estimates for each year.

FIGURE 4

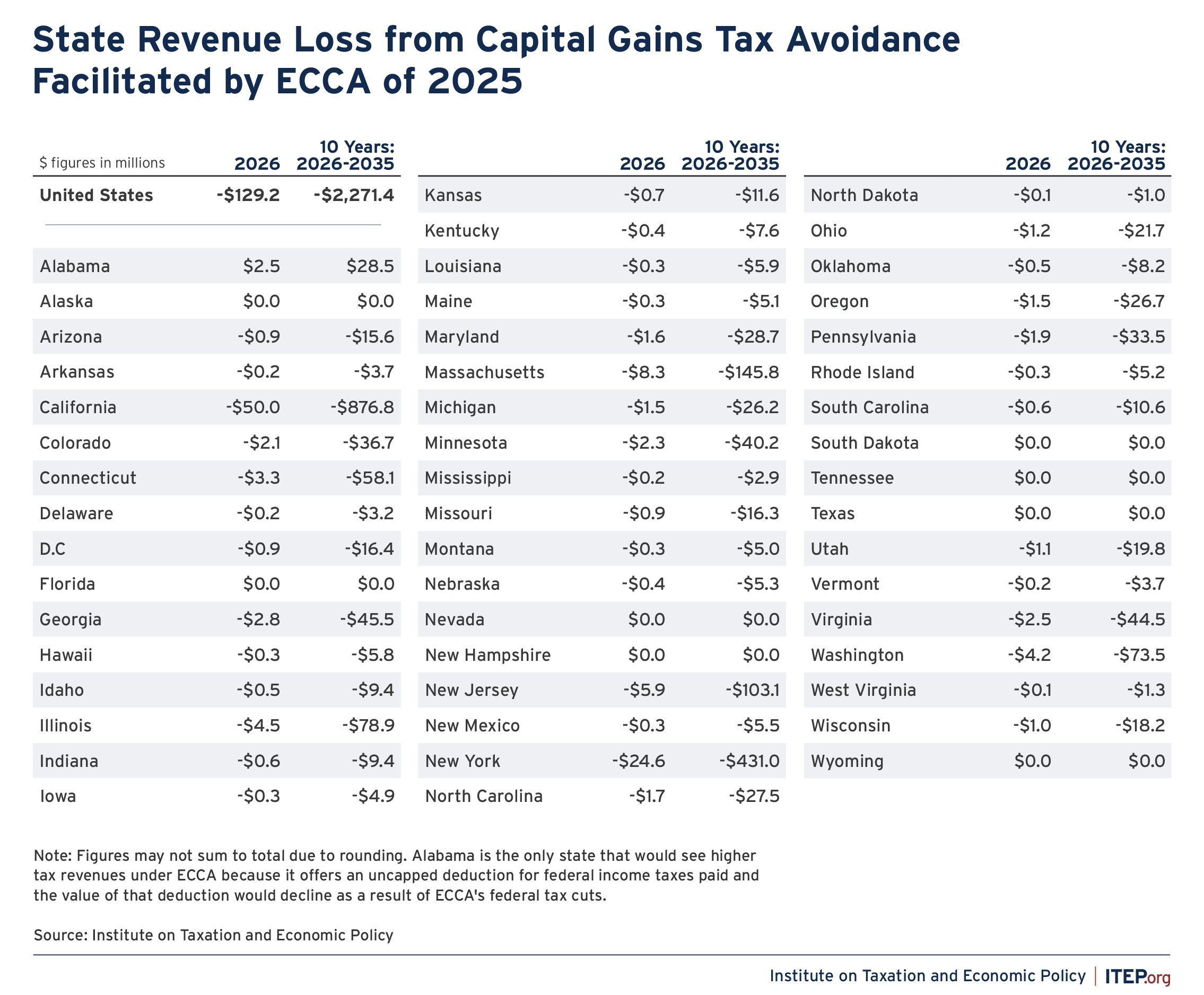

Results by state are disaggregated in Figure 5. The total result is a state revenue loss of $2.3 billion over 10 years, including $129 million in 2026 and $320 million annually by 2035. The bulk of these revenue losses would be concentrated in states with larger populations of high-income investors and with higher tax rates on long-term capital gains. More than two-thirds (69 percent) of the foregone revenue is attributable to four states: California, New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey.

FIGURE 5

Conclusion

The Educational Choice for Children Act of 2025 would reduce federal revenue not just through its provision of new federal tax credits, but also by facilitating capital gains tax avoidance. In total, ECCA would reduce federal tax revenues by almost $134 billion over the next 10 years. This figure reflects a $10.5 billion annual revenue reduction in 2026 that would rise to $16.7 billion by 2035.

States would also experience revenue losses as ECCA would remove $38.8 billion in capital gains income from their tax bases over the next decade. As a result, states could expect to face $2.3 billion in revenue losses over the next decade. Of that total, $129 million would come in 2026 and the revenue loss would rise to $320 million annually by 2035.

Endnotes

[1] While the contributions can also be used to fund homeschooling and educational expenses other than private school tuition, in practice the vast majority of these contributions will be steered toward paying for private school tuition.

[2] The final regulations were issued as T.D. 9864, Contributions in Exchange for State or Local Tax Credits, on June 13, 2019. See also: Davis, Carl. “New SALT Workaround Regulations Narrow a Tax Shelter, but Work Remains to Close it Entirely.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. June 2019.

[3] This 4.7 percent median was calculated using a combination of data from NBER’s TAXSIM and information from state revenue agencies.

[4] While the phrase “tax shelter” does not have a universally agreed upon definition, one common theme in definitions is that it is often used to describe actions undertaken largely, or exclusively, for tax avoidance purposes. 26 U.S. Code §6662(d)(2)(C)(ii), for example, offers a definition of “tax shelter” that includes “any investment plan or arrangement… if a significant purpose of such… plan, or arrangement is the avoidance or evasion of Federal income tax.”

[5] Video of the relevant portion of the U.S. House Ways & Means Committee markup of a previous version of ECCA (H.R. 9462 of the 118th Congress) can be viewed here.

[6] The Independence Academy in Indianapolis, Indiana, for example, says that donations made under the state’s tax credit program can take them for of either cash or stock, and that “stock donations are a popular option, as donors can save even more on their taxes by eliminating capital gains on those donated assets.” See: Independence Academy, “Tax Credit Program,” website accessed February 2025.

Other examples of schools and financial advisors describing these tax credits as a way to avoid capital gains tax are described in:

Davis, Carl. “Tax Avoidance Continues to Fuel School Privatization Efforts.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. March 2023.

Pudelski, Sasha and Carl Davis. “Public Loss Private Gain: How School Voucher Tax Shelters Undermine Public Education.” Joint report by the School Superintendents Association and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. May 2017.

[7] Davis, Carl. “Voucher Boondoggle: House Advances Plan to Give the Wealthy $1.20 for Every $1 They Steer to Private K-12 Schools.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. September 2024.

[8] Davis, Carl. “Tax Avoidance Continues to Fuel School Privatization Efforts.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. March 2023.

[9] Davis, Carl. “ITEP Comments and Recommendations on Proposed Section 170 Regulation (REG-112176-18).” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. October 2018.

[10] The most recent IRS data report $450 billion in corporate stock sales subject to long-term capital gains tax in 2015, including $40 billion in the month of January. Aging those figures to January 2026 levels using data on overall net capital gains income from IRS (for 2015-2022) and CBO (for 2022-2026) yields predictions of $630 billion in annual sales volume and $57 billion in January volume.

[11] The IRS does not report the sales volume of corporate stock by income level, but the five most recent years of IRS data (2018-2022) each show between 64 and 70 percent of net realized capital gains income on taxable returns flowing to tax units with AGI over $1 million.

[12] See note 9 and also: ITEP et al. “Letter to IRS on Section 1001 Regulation in 2023-2024 Priority Guidance Plan.” June 2023.

[13] In RIN 1545-BO89, it noted that “the Treasury Department and the IRS agree with commenters that additional guidance is necessary to address … complex issues” raised by commenters who suggested that “additional guidance may be needed to clarify application of the rules under sections… 1001,” pertaining to the determination of recognition of capital gain and loss.

[14] Video of the relevant portion of the U.S. House Ways & Means Committee markup of a previous version of ECCA (H.R. 9462 of the 118th Congress) can be viewed here.

[15] We assume that all stock contributed under ECCA would eventually have been sold by its current owner because stock that the taxpayer expects to hold until death will receive a stepped-up basis benefit that renders the ECCA tax shelter unnecessary.

[16] We examine gains transactions rather than loss transactions or net transactions because the tax shelter facilitated by ECCA only works in the context of appreciated securities.

[17] Congressional Budget Office. “Taxing Capital Income: Effective Marginal Tax Rates Under 2014 Law and Selected Policy Options.” CBO Publication 49817. December 2014.

[18] These shares exhibit meaningful volatility across years and thus a 5-year average allows us to produce estimates that will be more representative of what states could expect, moving forward, in a typical year.