This brief was updated September 2017

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a policy designed to bolster the earnings of low-wage workers and offset some of the taxes they pay, providing the opportunity for struggling families to step up and out of poverty toward meaningful economic security. The federal EITC has kept millions of Americans out of poverty since its enactment in the mid-1970s. Over the past several decades, the effectiveness of the EITC has been magnified as many states have enacted and later expanded their own credits.

In 2017, three states enacted new EITCs (Hawaii, Montana, and South Carolina) and two states improved existing credits (California and Illinois). The continued expansion of the EITC is as important as ever given the continuing challenges facing our country’s growing class of low-wage workers. Despite recent productivity gains, too many workers are facing low and slow-growing wages, while simultaneously feeling the squeeze of the growing costs of food, housing, child care, and other basic household expenses. To make matters worse, in all but one state, low-wage workers pay a higher share of their incomes in state and local taxes, leaving them with even fewer resources to make ends meet.[1]

The effectiveness of the EITC as an anti-poverty policy can be increased by expanding the credit at both the federal and state levels. To this end, this policy brief provides an overview of the federal and state EITCs and highlights recent trends to strengthen these credits.

The Federal Earned Income Tax Credit

The federal EITC has been rewarding work and boosting the income of low-wage workers since it was introduced in 1975. Since that time, the EITC has been improved to lift and keep more working families out of poverty. The most recent improvements enhanced the credit for families with three or more children and for married couples. First enacted temporarily as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in 2009, these changes were made permanent in late 2015.

The federal EITC returned nearly $67 billion in wages to 27 million working families and individuals in 2015.[2] Used mostly as a source of temporary support, the EITC helps millions of families each year–including veterans making their way back into the civilian workforce–cope with job loss, reduced hours, or reduced pay. Recognized widely as an effective anti-poverty tool, the federal EITC also lifted an estimated 6.5 million people out of poverty in 2015.[3]

To encourage greater participation in the workforce, the EITC is based on earned income, such as salaries and wages. For example, for each dollar earned up to $14,040 in 2017, families with three children will receive a tax credit equal to 45 percent of those earnings, up to a maximum credit of $6,318. Because the credit is designed to provide targeted tax cuts to the working poor, there are income limits that restrict eligibility for the credit. Families continue to be eligible for the maximum credit until income reaches $18,340 (or $23,890 for married-couple families). Above this income level, the value of the credit is gradually reduced to zero and is unavailable when family income exceeds the maximum eligibility level. The credit is entirely unavailable to families with three or more children earning more than $48,340 if the head of household is single and $53,930 if married. For taxpayers without children, the credit is less generous: the maximum credit is $510 and singles earning more than $15,110 (or $20,600 for married couples without children) are ineligible.

State Earned Income Tax Credits

In addition to helping working families afford the necessities that keep them working, EITCs at the state level play a very important function in improving the fairness of upside down state and local tax systems. Unlike federal taxes, state and local taxes are regressive, requiring low- and moderate-income families to pay more of their income in taxes than wealthier taxpayers. According to ITEP’s 2015 Who Pays? report, the poorest twenty percent of Americans pay 10.9 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes. By contrast, middle-income taxpayers pay 9.4 percent and the wealthiest one percent of taxpayers pay just 5.4 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes. Heavy use of regressive sales and property taxes (all of which working families pay) drive the high state and local tax rates faced by the poorest Americans. A refundable state EITC is among the most effective and targeted tax reduction strategies to help offset these regressive taxes.

Refundability is key to the EITC’s success, especially at the state level. If a credit is refundable, taxpayers receive a refund for the portion of the credit that exceeds their income tax bill. Refundable credits can therefore be used to help offset all taxes paid, not just income taxes, thereby offsetting some of the regressive effects of state and local sales, excise, and property taxes.

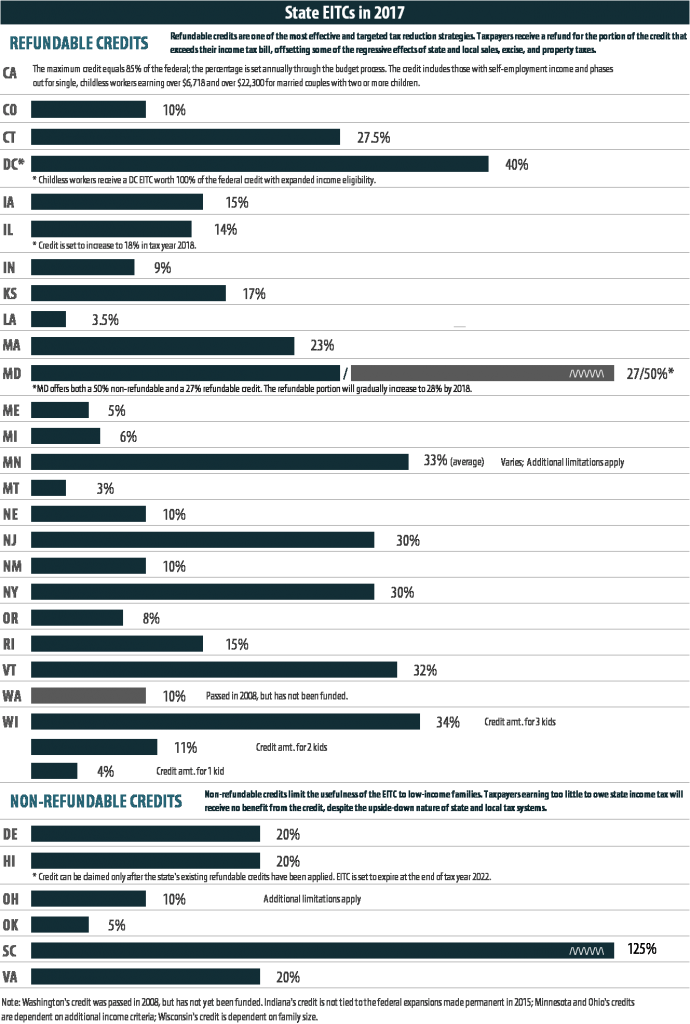

More than half of the states (twenty-nine states plus DC) offer state EITCs based on the federal credit (see chart on the following page). Most states allow taxpayers to calculate their EITC as a percentage of the federal credit. This approach makes the credit easy for state taxpayers to claim (since they have already calculated the amount of their federal credit) and straightforward for state tax administrators. However, states vary dramatically in the generosity of their credits. The EITC provided by the District of Columbia, for example, amounts to 40 percent of the federal credit (100 percent for childless workers), while eight states have credits that are worth less than 10 percent of the federal credit. Six states (Delaware, Ohio, Oklahoma, Virginia, and recently Hawaii and South Carolina) allow only a non-refundable credit, limiting the ability of the credit to offset regressive state and local taxes.

New Trends and Forward Momentum

Since 2015, four states have added new state-level credits and eight states have improved upon existing credits. This year alone, Hawaii, Montana, and South Carolina enacted new state EITCs. Montana lawmakers enacted a refundable state-level EITC equal to 3 percent of the federal credit. While this represents a meaningful step toward poverty alleviation in Big Sky Country, the 3 percent credit is the lowest in the nation—behind Louisiana’s 3.5 percent credit. Lawmakers in Hawaii passed legislation to create a 6-year nonrefundable state-level EITC equal to 20 percent of the federal. South Carolina lawmakers enacted a nonrefundable EITC equal to 125 percent of the federal credit. An EITC in a state that once had none is always welcome news, but in South Carolina’s case the impact of the credit can be misleading given its high percentage of the federal credit. Because the credit is nonrefundable, only 2% of South Carolinians with incomes below $21,000 will benefit from the new EITC.

In addition to the newly added credits, there have also been a number of advancements in existing EITC policy. Two years after enacting an EITC, lawmakers in California expanded the parameters of their state-level credit. Now families with incomes under $22,300 (up from around $14,000) can qualify, including those with income from self-employment. In Illinois, lawmakers increased the state’s EITC to 14 percent in 2017 (up from 10 percent). The credit will again increase to 18 percent in 2018. Lawmakers in Oregon and Massachusetts also made improvements. In Oregon, a law was passed to raise awareness about both the state and federal EITCs, with the goal of increasing uptake rates. The law requires W-2 employees to receive a notice about the federal and state EITC, encouraging families who quality to claim the credit. And, in Massachusetts, lawmakers expanded the state’s EITC access to domestic violence survivors and abandoned spouses.

At the federal level, there have been some recent efforts to expand the EITC for workers without children. While the federal EITC provides a great deal of assistance to families with children, its impact is quite limited for those without children; the maximum credit is much smaller and the income limits are more restrictive. For instance, under current law, a childless adult or noncustodial parent working full-time at the federal minimum wage is ineligible for the EITC. Yet, if this person had children they would receive the maximum EITC. Under the current system, these low-wage workers continue to be taxed deeper into poverty.

Former president Barrack Obama proposed expanding the federal EITC to workers without children in 2014 and again reiterated support in his 2015 State of the Union address and 2016-2017 budget proposal. Since then, multiple proposals, from both sides of the aisle, have been put forward on the federal stage. Most recently, Senator Sherrod Brown reintroduced his Working Families Tax Relief Act which would, among other things, increase the credit for workers without children in the home and expand it to workers between 21 and 24 years of age. At the state level, the District of Columbia is leading the way. Since January 2015, more childless workers qualify for DC’s EITC thanks to higher income eligibility thresholds and a credit expanded to 100 percent of federal (up from 40 percent).

Improving Tax Fairness with State EITCs

Whether enacting an EITC in states that do not yet have one or expanding an existing credit to more workers trying to get by on low wages, lawmakers would be wise to continue the positive trend of strengthening and enacting state EITCs and, as a result, improving the fairness of state and local taxes, rewarding work, and helping families meet their basic needs.

[1] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax System in All Fifty States, 5th Edition, January 2015. www.whopays.org

[2] https://www.eitc.irs.gov/EITC-Central/eitcstats

[3] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Policy Basics: The Earned Income Tax Credit, October 2016. http://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-the-earned-income-tax-credit