States often link their tax laws to the federal code in significant ways. Many of these links are justified and can simplify tax administration for both taxpayers and state officials. But in other cases, something can get lost in translation, and states end up copying federal provisions that just don’t make sense at the state level. State conformity to the federal government’s deduction for Foreign-Derived Deduction Eligible Income (FDDEI) offers a case study in the perils of conforming too casually to federal law, with revenue losses for individual states frequently running in the tens of millions of dollars per year.

The FDDEI deduction is designed to lower the federal corporate tax rate on some profits generated from exports, meaning sales to customers in foreign countries. The deduction, which now stands at 33.34 percent of eligible profits, is the successor to the deduction for Foreign-Derived Intangible Income (FDII), which was created by a major federal tax rewrite enacted in 2017.

The merits of the federal FDDEI deduction are disputed, though one could argue that it at least was created with a certain logic in mind. The same cannot be said for state-level FDDEI deductions. Crucially, it is not necessary to render judgment on the deduction as federal-level policy to decide whether it makes sense for states. It does not.

The FDDEI deduction comes out of pre-apportionment income, meaning the big pool of corporate profit that is tallied up on federal forms. Because of this, federal FDDEI deductions that a company generates from activity in one state will flow through as a tax break being offered by all states with FDDEI deductions. Arizona and Florida, for instance, currently offer FDDEI deductions for export sales originating out of states like California and New York, with no economic benefit for their own states. In fact, ITEP’s analysis of corporate financial disclosures suggests that a significant share of these deductions has gone to tech companies headquartered in California and Washington. In its most recent financial statement, for instance, Netflix revealed that it expects to receive a staggering $657 million federal tax cut in 2025 alone from this deduction. The fact that the federal government has decided to levy a lower tax rate on FDDEI profits is simply not a compelling rationale for states to do the same. The states, of course, get to set their own tax rates.

Moreover, in most states with FDDEI deductions, there is yet another reason why that deduction is nonsensical. Unlike at the federal level, most states use what’s known as single sales factor apportionment to determine the share of a company’s profit that it will tax. If 5 percent of a company’s sales occur in a state, for instance, then 5 percent of that company’s profits are fair game to tax. The intent of the single sales factor approach is to tax profits arising from sales to customers located within a state’s borders, while exempting profits from sales into other states or countries. The upshot is that those states using single sales factor apportionment are already aiming to exclude export profits from their state tax bases, and a 33.34 percent FDDEI deduction for export profits goes much further and actually subsidizes them (again, regardless of whether the sales originate in that state or not).

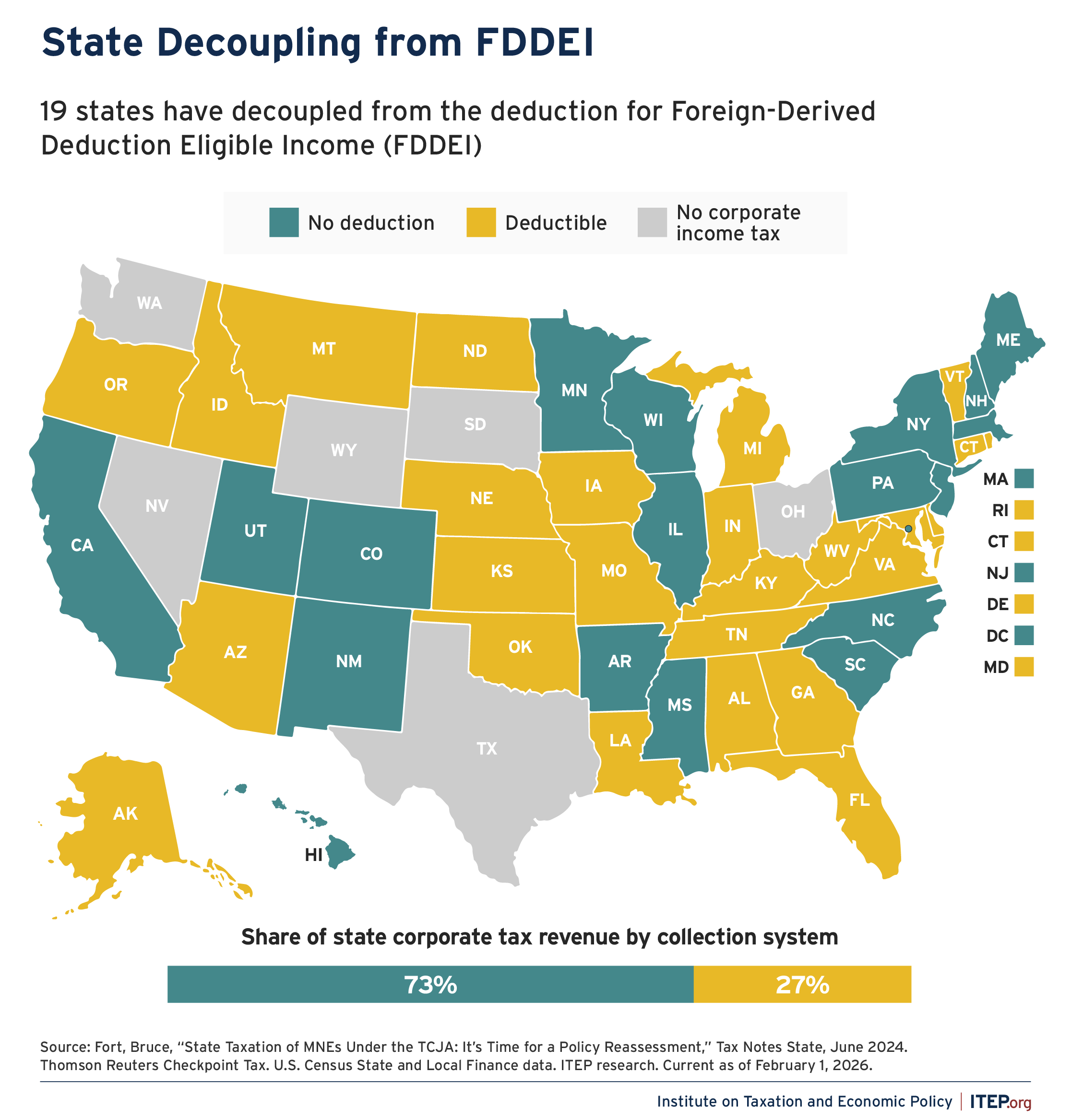

Figure 1

Nineteen states have decoupled from FDDEI deductions, while 26 states continue to offer them today. In many of these states, these deductions appear to be holdovers from the very busy 2018 slate of state legislative sessions. The original version of this deduction (FDII) was signed into law in late December 2017, alongside a host of other complex and highly consequential corporate tax changes, and states coming into legislative sessions that next month had precious little time to puzzle through the best means of linking up to a dramatically reworked federal tax code. After that, once a new deduction is on the books, it tends to stick around for a while.

With the transformation from FDII to FDDEI, this is a natural time for states to revisit whether this deduction makes sense for them. Most large states with corporate income taxes have already removed this deduction for their codes, and our analysis of state tax revenue data reveals that around three-quarters of state corporate income tax revenue is being collected in states that do not provide FDDEI deductions. In other words, multinational companies are already accustomed to paying most of their state corporate tax liability under rules that do not provide for FDDEI deductions.

In the states allowing FDDEI deductions, the revenue loss associated with them is potentially significant. Colorado, the most recent state to repeal this policy, estimated in September that doing so will boost state revenues by more than $72 million per year. In Oregon, officials have placed the price tag of the deduction at roughly $60 million per year, while in Georgia the official estimate is $24 million. The other states offering this deduction do not report its cost in their official tax expenditure reports, making it difficult for lawmakers to know exactly how much revenue is being forgone.

To begin to shed some light on this question, Figure 2 presents rough estimates of the state revenue loss created by FDDEI deductions. These estimates were compiled by starting from the $14.3 billion nationwide estimate produced by Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation, apportioning it across states using a method described in previous ITEP research, and then scaling it based on the difference between state and federal corporate income tax rates. This calculation yields an estimate for Oregon that almost exactly matches the official tally from the state’s Department of Revenue, and it comes within 25 percent of the estimate released by Colorado Legislative Council Staff. The estimate in Figure 2 for Georgia, however, is significantly higher than the one published in the state’s official tax expenditure report. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, but lawmakers in any state seeking to repeal the FDDEI deduction would be wise to request an official revenue estimate from state tax authorities who have access to confidential taxpayer data that can be used to produce more refined estimates than those presented here.

Revenue implications aside, FDDEI deductions should be repealed for policy reasons alone as they do not serve a legitimate purpose at the state level. These deductions have flown under the radar for too long and, with federal tax conformity top of mind in many states, now is the perfect time to pursue this overdue reform.