Update (February 2026): The District of Columbia and Pennsylvania passed EITC expansions in late 2025 that will go into effect in 2026. The District of Columbia will now match 100 percent of the federal EITC for all filers, and Pennsylvania will now administer a 10 percent refundable EITC. These are not included in the numerical counts in this brief.

Key Takeaways

- Nearly two-thirds of states (31 plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) have an Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). These credits boost low-paid workers’ incomes and offset some of the taxes they pay, helping lower-income families achieve greater economic security.

- These state credits are usually built on the federal EITC, which delivered about $64 billion to 23 million working families and individuals in 2024. Along with the federal Child Tax Credit, the EITC lifted an estimated 6.8 million people out of poverty in 2024.

- To maximize the impact of their state credits, lawmakers should ensure EITCs are fully refundable, structured with a robust matching percentage, and enhanced for older and younger workers without dependent children in the home. Other potential reforms to consider include enhancing the credit for extremely low-income families and enabling monthly payments in lieu of an annual lump sum.

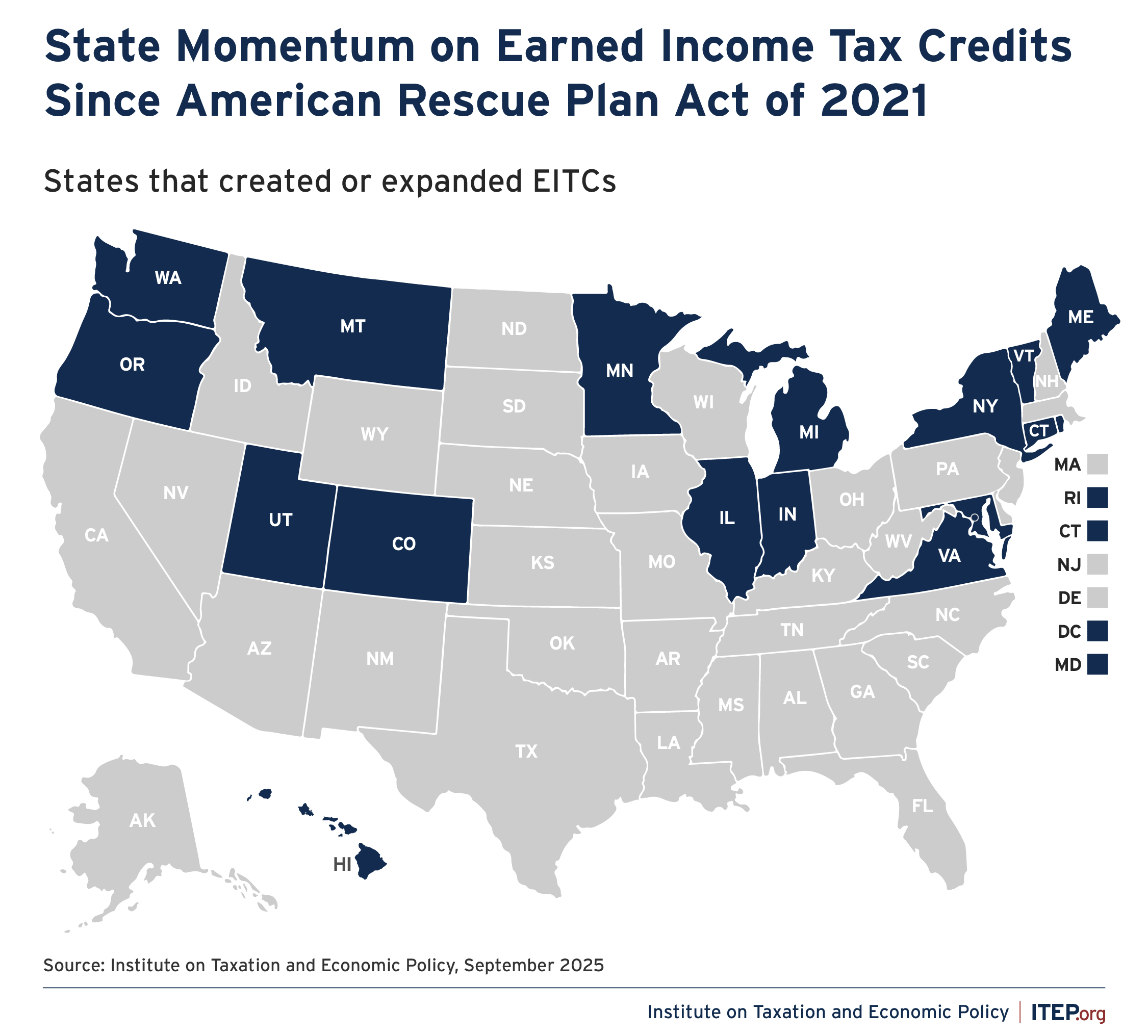

- Following the expiration of the federal EITC expansion under the American Rescue Plan Act, 17 states and the District of Columbia have enacted or expanded state EITCs.

Introduction

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) boosts low-paid workers’ incomes and offsets some of the taxes they pay, helping lower-income families achieve greater economic security. The federal EITC – which celebrated its 50th anniversary this year – has kept millions of Americans above the poverty line since its enactment in the mid-1970s. Over the past several decades, the EITC’s effectiveness has been amplified as many states have enacted and strengthened their own credits. Since federal lawmakers allowed EITC expansions passed through the American Rescue Plan Act to lapse in 2022, 17 states and the District of Columbia have created or expanded state EITCs. This year, Connecticut, Montana, Vermont, and Virginia became the most recent states to improve their credits.

The EITC benefits low-income workers of all races and ethnicities. It is particularly beneficial to Black and Hispanic communities where discrimination in the labor market, underfunded education systems, and countless other inequities have relegated a disproportionate share of people to low-paid jobs.

The effects of the EITC have been studied for decades, and research consistently shows that children whose families received the credit are more likely to graduate from high school, go to college, and be employed as adults.1 In addition to boosting financial security for working families with children, the EITC also improves health outcomes and is connected to a reduction in babies born with low birthweights.2

Proven and effective income supports like the EITC are more important than ever. Too many workers face low and slow-growing wages while simultaneously facing high costs for housing, child care, and other basic expenses. In 41 states, low-income households also pay a higher share of their incomes in state and local taxes than the richest households.3 This leaves working families with even fewer resources to make ends meet and contributes to income and wealth inequality. These outcomes will only be compounded by the recent passage of the 2025 federal tax and spending legislation, which will cut services many EITC-eligible families use to make ends meet for their families. Creating or expanding a state EITC can counteract inequities in state tax codes while boosting the incomes of low- and moderate-income workers.

Federal Earned Income Tax Credit Provides Income Boost to Millions

The federal EITC has been boosting the incomes of low-paid workers for 50 years, since 1975. Lawmakers have improved the credit over time so more working families can put food on the table, pay their bills, and have more economic stability.

The federal EITC delivered about $64 billion to 23 million working families and individuals in 2024 through claims on their 2023 tax returns.4 The federal EITC, together with the federal Child Tax Credit, lifted an estimated 6.8 million people out of poverty in 2024.5

Although the EITC does a lot to reduce poverty, a more robust EITC did so to a greater extent in 2021. As a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the American Rescue Plan Act temporarily increased the federal EITC for low-paid workers without children in the home and made it more widely available by expanding age and income limits. These enhancements expired on January 1, 2022. The improved federal EITC delivered about $60 billion to 25 million working families and individuals in 2021. The stronger federal EITC, together with an enhanced federal Child Tax Credit in place for 2021, lifted an estimated 9.6 million people out of poverty in 2021 compared to 6.8 million in 2024.6

The EITC is based on earned income like salaries and wages. For each dollar earned up to $17,880 in 2025, families with three or more children will receive a tax credit equal to 45 percent of those earnings, up to a maximum of $8,046. The credit is designed to boost incomes for low- and moderate-income workers, phasing out as incomes rise. Families are eligible for the maximum credit until income reaches $23,350 for single heads of household. Above this level, the credit gradually decreases and becomes unavailable when family income exceeds the maximum eligibility level. Single-parent households with three or more children earning $61,555 or more in 2025 are ineligible, as are married couples earning $68,675 or more. The credit is small and not widely available for workers without children in the home: the maximum credit for these workers is $649.

State Earned Income Tax Credits Help Low-Paid Workers and Improve State Tax Systems

In addition to helping working families afford child care, health care, housing, food, and other necessities, state EITCs improve state and local tax systems. Unlike federal taxes, state and local taxes as a whole are regressive, requiring low- and moderate-income families to pay a greater share of their incomes than wealthier taxpayers. The poorest 20 percent of Americans pay 11.4 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes. By contrast, middle-income taxpayers pay 10.5 percent, and the wealthiest 1 percent of taxpayers pay just 7.2 percent.7

Regressive sales and property taxes (which all working families pay whether renting or owning property) create the high state and local tax rates faced by the poorest households. A refundable state EITC is among the most effective and targeted strategies to help counterbalance these regressive taxes.

Refundability is vital because it ensures that workers and their families get the full benefit of the credit. Refundable credits do not depend on the amount of income taxes paid; rather, if the credit exceeds income tax liability, the taxpayer receives the excess as a refund. This makes these credits more effective at offsetting regressive sales and property taxes and at boosting incomes. This is essential because for lower-income families, sales and property taxes—not income taxes—make up the bulk of state and local taxes paid.

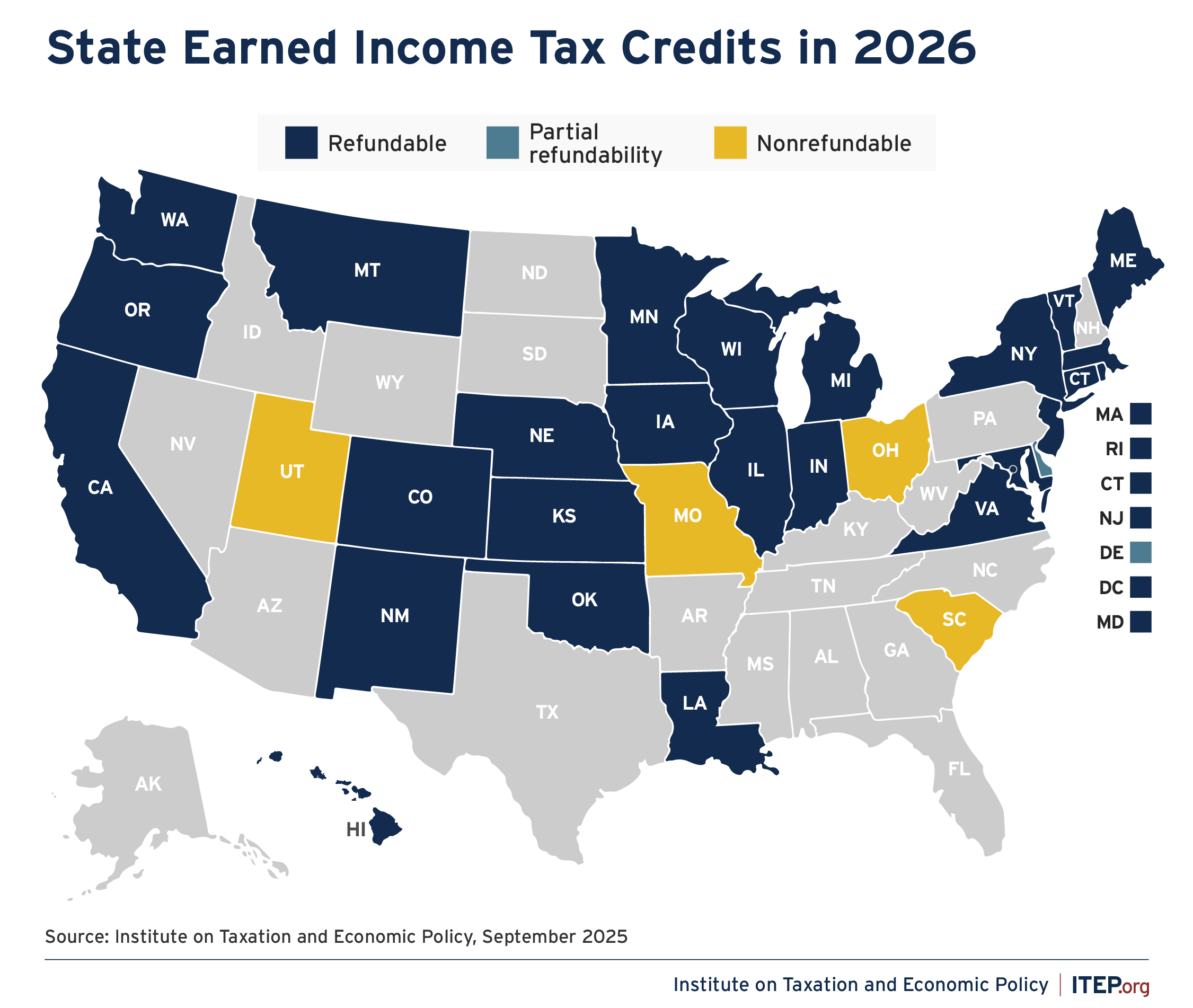

Nearly two-thirds of states (31 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) offer EITCs (see Appendix). With a few exceptions (California, Minnesota, and Washington), taxpayers calculate their state EITC as a percentage of the federal credit. This makes it easy for people to claim the credit (since they have already calculated their federal credit) and straightforward for state tax administrators. There are, however, good reasons to decouple from aspects of the federal credit to strengthen the benefits to workers without children in the home and extremely low-income families.

States vary dramatically in the generosity of their credits. The EITC provided by the District of Columbia, for example, is 85 percent of the federal credit this year for most eligible families, increasing to 100 percent in 2029 (matching its existing 100 percent credit for workers without dependents in the home).

Figure 1

Meanwhile, four states (Delaware, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Oregon) have refundable EITCs that are worth less than 10 percent of the federal credit for most families. Four other states (Missouri, Ohio, South Carolina, and Utah) allow only a nonrefundable credit, which limits the ability of the credit to offset regressive state and local taxes. Delaware is now the only state to offer partial refundability, which allows taxpayers to choose between a refundable or nonrefundable credit, after Virginia moved to a fully-refundable credit through 2026.

Recent Progress Toward Expanded EITCs

State lawmakers have made the creation and enhancement of EITCs a priority in recent years. The American Rescue Plan Act significantly expanded refundable credits like the EITC in 2021, and state lawmakers quickly understood the impact these boosted credits had in helping workers and families make ends meet. While federal lawmakers failed to extend these expansions beyond 2021, state legislators picked up the baton and accelerated the creation and improvement of state-level refundable credits. Since 2021, 17 states and the District of Columbia have enacted or boosted EITCs. Eight of these states have boosted their credits multiple times over that period.

Figure 2

Four states expanded or increased their EITCs in 2025. Lawmakers in Connecticut implemented a $250 boost for households receiving the EITC with dependents – a compromise to an initially proposed Child Tax Credit. Montana doubled its refundable EITC from 10 to 20 percent as part of a larger regressive tax cut package. Virginia is now offering a 20 percent refundable credit to all qualifying households after previously offering the option of a 20 percent nonrefundable or 15 percent refundable credit. Vermont increased its credit match for workers without children in the home from 38 to 100 percent.8

There are several best practices for states looking to increase the impact of their EITCs:

- Make the credit fully refundable

- Structure the credit with a robust matching percentage

- Loosen restrictions on the age of eligible workers

- Increase the credit for workers without children in the home

- Boost the credit for extremely low-income families

- Consider monthly payment options

- Ideally, all workers and families should be included, regardless of immigration status, in credit eligibility. However, caution should be used given recent drastic shifts in policy that have fundamentally changed the nature of immigrants’ relationship with the tax code and tax filing.9

These actions can chip away at racial and wealth inequality, blunt some of the regressivity of state and local tax systems, and help families meet their basic needs. Lawmakers should enact and strengthen state EITCs with these concepts in mind.

In recent years, the District of Columbia and Washington state have exemplified EITC best practices. D.C. set the standard for boosting and expanding state credits to surpass the federal EITC (a move to 100 percent of the federal credit for all filers in 2029, plus expanded income eligibility). Part of D.C.’s EITC will also be available to recipients in monthly payments. Washington, which lacks a state income tax, modeled its Working Families Tax Credit after the federal EITC and enhanced it by allowing all families with any amount of earned income to qualify for the credit’s full value. The state has had an EITC on the books since 2008 but it was not until 2023 that lawmakers improved its structure and fully funded its implementation.

Expanding Age Eligibility and Increasing the Credit for Childless Workers

A growing number of states have chosen to expand the EITC for workers without children in the home. While the federal EITC provides strong support to families with children, its impact is limited for those without children because the maximum credit is much smaller and the income limits are more restrictive. For instance, a worker without dependent children in the home who is working full-time at the federal minimum wage is ineligible for the EITC. Under the current federal income tax system, these low-paid workers are taxed deeper into poverty.

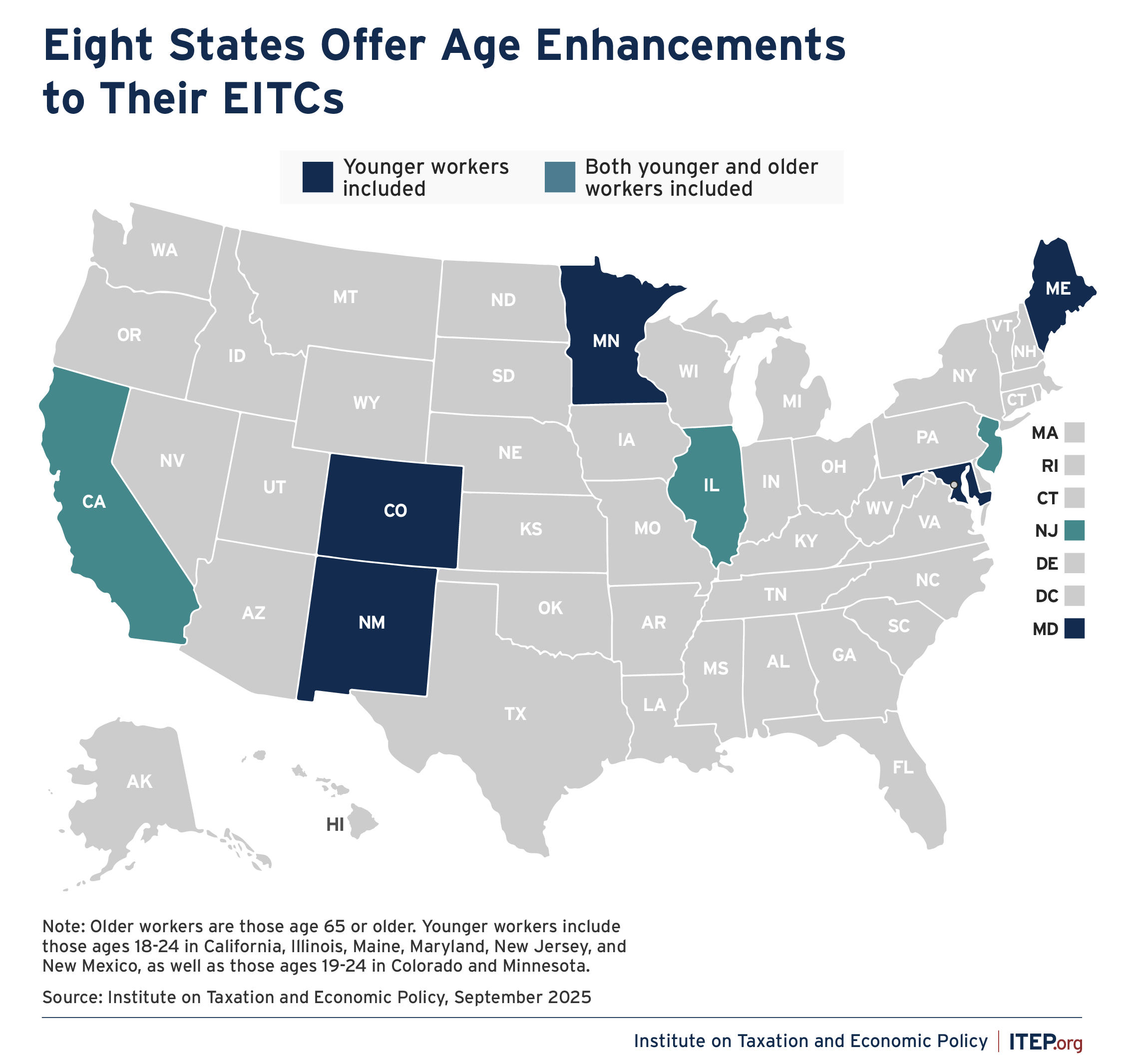

Figure 3

The temporary expansion of the federal EITC in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 expanded age eligibility to include both younger and older low-income workers without dependent children. That expansion was allowed to lapse, however, meaning that once again the federal EITC excludes people under age 25 and over age 64 unless they have children in the home. These workers include noncustodial parents, young workers getting a foothold in the job market, and older workers who need to work past the traditional retirement age and who often struggle to make ends meet.10 Because state EITCs are generally linked to the federal credit, these workers are excluded from most state EITCs as well.

Eight states now recognize the need to provide more young workers the benefits of the EITC. And three states have expanded access to include older workers (ages 65+) without dependent children in the home. Most of these credit expansions for childless workers have occurred in the last few years. In 2022, for instance, Illinois and Maine enhanced their credits to benefit workers without children in the home. Lawmakers in Illinois lowered the state’s minimum age of eligibility to 18 and expanded the credit to those 65 and older. Maine lawmakers doubled the credit size for their childless population from 25 to 50 percent of the federal level. In 2021, Maryland, New Jersey, and New Mexico permanently lowered the age floor on their existing credits to include 18- to 24-year-old workers without dependents. California and Maine also include workers between the ages of 18 to 24 without children in the home, while Colorado and Minnesota set their age eligibility floor at 19.

Local EITCs

A few localities have their own version of an EITC, most notably New York City and Maryland’s Montgomery County.11 These are provided on top of state credits, delivering an added boost for low-income working families. EITC.

In New York City, a local EITC matches between 10 and 30 percent of the federal EITC, with the highest match rates to households with very low incomes. A low-income worker in New York City can receive a combined state and local boost worth up to 60 percent of the federal EITC.

In Montgomery County, a refundable EITC matches 25 percent of the federal EITC for families and 56 percent of the federal EITC for workers without children in the home. A low-income worker in Montgomery County can receive a combined refundable state and local boost worth 70 percent of the federal EITC for families with children and 156 percent of the federal EITC for workers without children. In addition, all Maryland counties and the city of Baltimore provide nonrefundable EITCs to offset local income taxes.

State lawmakers should ensure that localities are given the autonomy to create their own EITCs, and local lawmakers should consider pursuing these credits to bolster the economic security of residents working low-paid jobs.

Endnotes

- 1. Bastian, Jacob, and Katherine Michelmore. The Long-Term Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Children’s Education and Employment Outcomes. Journal of Labor Economics, Volume 36, Number 4. October 2018.

- 2. “Earned Income Tax Credits: Interventions Addressing the Social Determinants of Health.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Accessed September 9, 2022.

- 3. Davis, Carl, et al. “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax System in All Fifty States, 7th Edition,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2024.

- 4. Internal Revenue Service. “EITC Reports and Statistics.” Last updated January 16, 2025.

- 5. Poverty in the United States: 2024. United States Census Bureau, September 9, 2025.

- 6. Poverty in the United States: 2024. United States Census Bureau, September 9, 2025.

- 7. Davis, Carl, et al. “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax System in All Fifty States, 7th Edition,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2024.

- 8. Butkus, Neva. “Which States Expanded Refundable Credits in 2025?“. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, July 24, 2025.

- 9. Over the past few years, 10 states and the District of Columbia have made their EITCs more inclusive than the federal credit by allowing immigrants filing with Individual Tax Identification Numbers (ITIN) to claim them. These reforms have helped to curb disparities in U.S. tax policy that result in immigrant families being treated more harshly than U.S. citizens. But while immigrant-inclusive tax credit policies have improved the lives of immigrant workers and their families up until this point, drastic shifts in policy under the Trump administrative have fundamentally changed the nature of immigrants’ relationship with the tax code and tax filing. Media reports indicate that, starting in August 2025, the IRS has begun sharing confidential taxpayer data with immigration enforcement authorities under an unprecedented and legally dubious agreement aimed at facilitating the deportation of immigrant tax filers. Furthermore, the Trump administration has also stated its intention to compel states to disclose a wide range of data relating to programs they administer, also with the goal of facilitating mass deportations. Against this backdrop, encouraging immigrants to file tax returns and to claim tax credits could also put them at risk. Mechanisms for protecting confidential tax filer data from immigration authorities must be devised to prevent this possibility.

- 10. See the following reports and posts by Aidan Davis at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy:

- – Federal EITC Enhancements Help More Than One in Three Young Workers

- – Nearly 20 Million Will Benefit if Congress Makes the EITC Enhancement Permanent

- – Expanding State EITCs: Age Enhancements and a Credit Increase for Workers without Children in the Home

- 11. Das, Kamolika, et al. “Local Earned Income Tax Credits: How Localities Are Boosting Economic Security and Advancing Equity with EITCs,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, October 30, 2023.