Read this Policy Brief in PDF Form

For much of the last century, estate and inheritance taxes have played an important role in helping states to adequately fund public services in a way that exempts middle- and low income taxpayers. This is an especially vital role at the state level because most of the taxes levied by state and local governments fall most heavily on low-income families. Recent changes in federal estate tax laws give states an opportunity to re-examine the design of their own estate and inheritance taxes. This policy brief discusses inheritance and estate taxes and how states can adopt these important components of a progressive tax structure.

For much of the last century, estate and inheritance taxes have played an important role in helping states to adequately fund public services in a way that exempts middle- and low income taxpayers. This is an especially vital role at the state level because most of the taxes levied by state and local governments fall most heavily on low-income families. Recent changes in federal estate tax laws give states an opportunity to re-examine the design of their own estate and inheritance taxes. This policy brief discusses inheritance and estate taxes and how states can adopt these important components of a progressive tax structure.

The Long History of Estate Taxes

Until 2001, levying a tax on the transfer of wealth from one generation to the next was one of the few things all fifty states could agree on. After the federal government enacted an estate tax in 1916 to “break up the swollen fortunes of the rich,” every state enacted a similar tax of its own. While these taxes typically represent only a small part of overall state tax collections, estate taxes (which are paid by taxable estates upon death) and inheritance taxes (which are paid by those individuals who receive gifts from estates) play an important role in reducing the transmission of concentrated wealth from one generation to the next. This function is now more important than ever: in 2007, the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans owned 33.8 percent of the wealth nationwide—more than the poorest 90 percent put together.

How the Federal and State Estate Taxes Work

The federal estate tax was designed to apply only to the very wealthiest Americans—and that’s exactly what it does. Nationwide, less than one percent of deaths in the U.S. in 2009 resulted in estate tax liability in 2010. (Estate taxes are usually filed during the year after the year in which a person dies.) This is primarily because the federal tax exempted the first $3.5 million of an estate’s value from tax in 2009. This is the most current data available because due to temporary tax changes enacted by the Bush administration, the federal tax disappeared entirely, for a single year, in 2010. In 2011 and 2012, the exemption amount increased to $5 million of an estate’s value.

Federal tax changes, however, continue to threaten the future of the estate tax at the state level. Since 1926, the federal estate tax allowed a dollar-for-dollar tax credit against the estate taxes levied by states, up to a certain maximum amount. The credit gave states an incentive to levy an estate tax at least as large as this credit: in the states levying a “pickup tax”—that is, a tax calculated to be exactly equal to the maximum federal tax credit—the state’s estate tax amounted only to a transfer of estate tax revenues from the federal government to the states. In other words, the pickup tax did not change the amount of estate tax paid—it just meant that part of the federal estate tax liability was being shared with, or “picked up” by, state governments.

Every state took advantage of this incentive to enact an estate tax at least as big as the pickup tax until 2001 when legislation signed into law by President Bush gradually repealed the federal estate tax over ten years. More importantly for the states, the estate tax cut phased out the federal credit allowed for state estate taxes between 2002 and 2005. In many of the states that base their tax on the federal credit, this meant that the state’s estate tax also ceased to exist in 2005, although a number of states took steps to prevent this accidental tax repeal.

Options for Reforming State Estate Taxes

The “pickup tax” credit was scheduled to come back to life along with the federal estate tax in 2011, but Congress instead extended the repeal of the credit and replaced it with a deduction for two years. Technically, the “pickup tax” credit is scheduled to come back to life in 2013, but most observers believe that Congress will change the law in a way that ends the state death tax credit permanently.

States seeking to preserve this important progressive revenue source have an easy way of doing so: “decoupling” from the federal tax repeal. The easiest way to achieve this is by defining the state estate tax to equal the federal credit as it existed in 2001—before the passage of the Bush administration’s estate tax cuts. States taking this step will effectively have a tax with a rate of 16 percent on estate value in excess of the federal lifetime exemption amount (which is $5 million for 2011 and 2012 and scheduled to revert to $1 million in 2013). States taking this step can also “piggyback” on special federal provisions that help to ensure that small businesses and family farms won’t be hit by the estate tax, including a provision assessing farmland according to its agricultural value, not its market value, an exemption for family-owned businesses above the basic amount, and a provision allowing certain estates to pay the estate tax over 14 years.

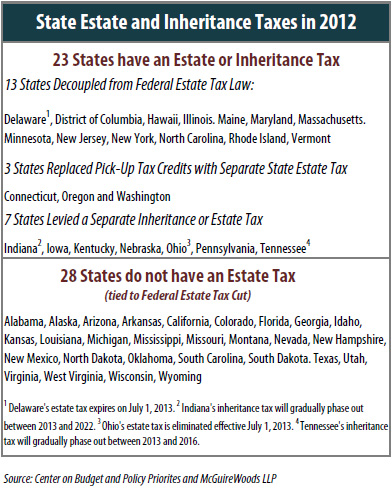

A number of states have made this simple administrative change already and decoupled from the federal tax including three that replaced their pick-up taxes with a stand-alone state estate tax. Seven other states are at least partially unaffected by the federal estate tax repeal because they already levied separate inheritance taxes, which are paid individually by those receiving transfers from an estate (by contrast, the estate tax is levied on the value of an entire estate, generally without regard to the way taxable estate value is split up between beneficiaries) or state estate taxes.

Decoupling could be enacted by more than half the states currently not imposing estate or inheritance taxes. This would be a sensible means of shoring up state revenues and restoring tax fairness.

Inheritance Taxes

Despite often being confused with estate taxes, inheritance taxes are slightly different mechanisms for taxing the transfer of wealth after a death. Inheritance taxes are paid not by the estate of the deceased, but by the inheritors of the estate. For example, the Kentucky inheritance tax “is a tax on the right to receive property from a decedent’s estate; both tax and exemptions are based on the relationship of the beneficiary to the decedent.” In Kentucky there are three classes of beneficiaries. If the beneficiaries of the estate are a parent, child, sibling, or grandchild or other close relation no inheritance tax is due. Nieces, nephews, aunts and other specific relations receive a $1,000 exemption and pay tax rates of 4 to 16 percent on their inheritance. Other classes of beneficiaries receive a $500 exemption and must apply tax rates between 6 and 16 percent to their gift. Inheritance taxes are a useful addition to a state’s tax structure to help ensure that a state’s tax structure is progressive because they can help offset regressive property and sales taxes.

Final Word

Estate and inheritance taxes can be one component of making a state’s tax structure less regressive. These taxes are paid by the best off taxpayers and are considered to be some of the most progressive taxes levied. Because the federal estate has weakened over the last decade, states have an opportunity to lead on this important issue and develop or even strengthen their estate and inheritance taxes.