We write often in this space—and since 1996 in our Who Pays? reports—about the economic and racial inequities that abound throughout the United States. Addressing these structural challenges requires more equitable and adequate funding for shared priorities like schools and healthcare, and state policies that mitigate these issues.

As the COVID-19 pandemic began, and again as 2020 drew to a close, we repeated our hope that these trying times would awaken and embolden state leaders to enact lasting solutions to emergent and long-standing needs in their states. Lawmakers in New Jersey and voters in Arizona helped set an example by taking progressive action in 2020.

Now, advocates, lawmakers, study commissions, and even governors in some states are proposing bold tax policy reforms that look beyond pandemic-induced budget shortfalls and the “K-shaped recovery” to address underlying inequities and underfunding that gave rise to them. These efforts include proposals to: end or reverse regressive tax policies like the preferential treatment of income derived from wealth over income earned through work; restore or strengthen estate and inheritance taxes to slow the concentration of wealth in ever-fewer hands; raise revenue and slow inequality with progressive income taxes; and many other ideas to right upside-down tax codes while raising the revenue needed to invest in families and shared priorities.

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz’s “Recovery Budget,” is about so much more than restoring the state to where it was before the pandemic. His proposal would reduce taxes for low-income families by stretching the lowest-income tax bracket, boosting the state’s Working Family Credit, and funding about $800 million annually in short- and long-term investments in Minnesotans. Gov. Walz’s proposal would pay for these measures with smart tax increases on those who can most afford to pay more, creating a new income tax bracket for individuals with income exceeding $500,000 ($1 million for married couples). It would also tax those who get their income from their existing wealth through a capital gains tax of 1.5 percent starting at $500,000 and 4 percent starting at $1 million. And the governor’s proposal would institute a 1.45 percentage-point increase in the corporate tax rate. Walz’s proposal would also tax repatriated foreign income, reinstate the estate tax threshold (except for small businesses and farms) to its previous $2.7 million level, and raise cigarette and vaping taxes.

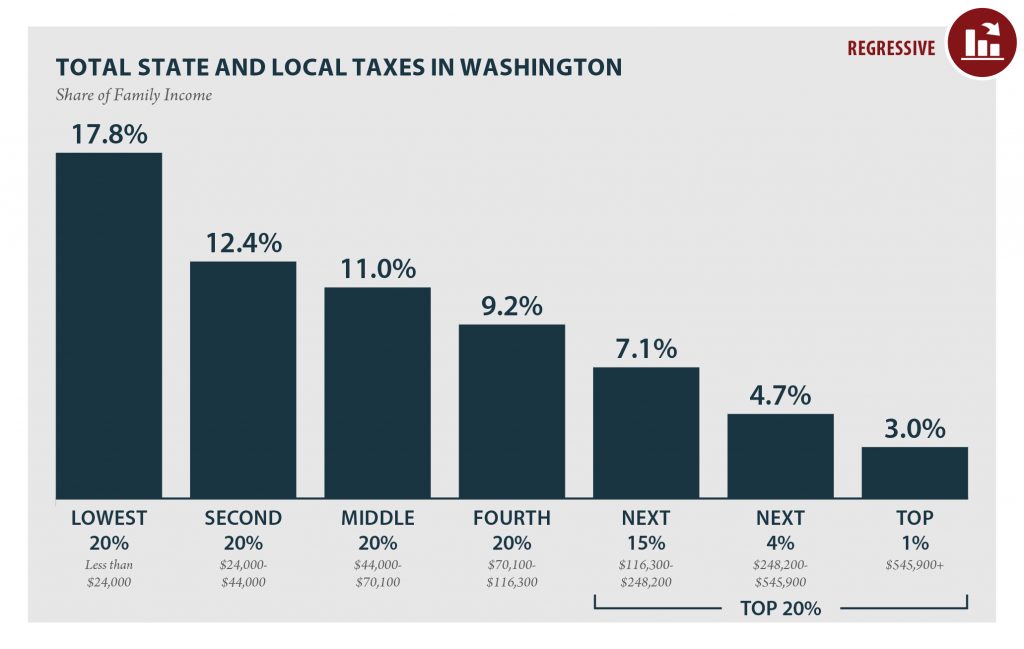

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee has fewer readily available progressive policy levers to pull because his state has no personal or corporate income taxes. His state has the most regressive tax code in the nation, which makes his innovative budget proposal that much more impressive. Refusing to simply “cut the things that we need most during a pandemic,” and insisting on “investing in the people of our state,” Inslee has proposed a new capital gains excise tax that would raise $3.5 billion for such investments over four years by taxing the sale of long-term capital assets (including stocks and bonds but excluding retirement accounts, homes and farms) at a rate of 9 percent when such sales exceed $25,000 ($50,000 for couples). Inslee has also embraced funding and enhancing the state’s Working Families Tax Credit, patterned after the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, to combine these tax increases at the top with reductions for low- and middle-income families.

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf also plans to get creative to add funding and fairness to his state’s revenue system. He proposes raising the state’s flat 3.07 percent income tax to 4.49 percent, while insulating low- and middle-income families from the rate increase by increasing the amount of income each family can exempt (from $6,500 to $15,000 per adult filer and from $9,500 to $10,000 per dependent). The net result, the governor’s office says, is a tax reduction for families of four with income below about $84,000—and a major, lasting investment in the quality and equity of Pennsylvania’s school system.

Thought leaders in Connecticut are making waves with progressive revenue solutions of their own. Connecticut Voices for Children released a major report in December, highlighting several tax policy options with the potential to “ensure that Connecticut’s tax system works to advance economic justice rather than continue to contribute to economic injustice.” Those options include: income tax increases on households with incomes over $500,000 ($1 million for couples) that could raise $504 million to $1.72 billion per year; estate tax improvements to reverse cuts and raise $108-162 million per year; a surcharge on capital gains and other similar income to raise $167-334 million per year; and a mansion tax on homes valued over $1.5 million that could raise $331-663 million. These ideas are already being reflected in bills to be considered by lawmakers this year.

Some New York advocates have set their sights even higher, offering policymakers a menu of very ambitious progressive tax increases they estimate would generate $50 billion per year to cover the state’s current $15 billion shortfall and address ongoing needs that have been underfunded for decades. Their ideas include: nine new personal income tax brackets beginning at $400,000 of taxable income; a capital gains tax based on the under-taxation of that income at the federal level; a new “mark-to-market” tax designed to tax capital gains annually rather than only when they are sold; a small tax on Wall Street financial transactions; reforms to the state’s corporate income tax to recapture tax breaks handed out to rich business owners under the 2017 federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA); and replacing the estate tax with a tax on inheritance income (with exemptions for most family homes and farms). Their bold aspirational vision stands in stark contrast to Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s timid proposal to slightly raise income taxes on millionaires and then refund most of the money back to them.

The Vermont Tax Structure Commission, a panel of experts tasked with undertaking an impartial study of what is working in the revenue system released a draft report featuring one key finding that has garnered national attention: funding schools through property taxes on homes—which is the fundamental approach nearly everywhere in the country—does not work. While property taxes are a form of wealth tax, they point out, homes are not a major form of wealth for the truly wealthy and thus are not a reasonable proxy for total worth or overall ability to pay. The authors demonstrate that income is in fact a better proxy and recommend replacing existing education property taxes on primary homes with local income taxes, while keeping taxes on other properties to be shared between districts. This would also allow the state to abandon existing complicated exemptions and offsetting credits meant to redress inequities in the property tax system, resulting in an education funding system that is both more effective and simpler.

While these six states stand out for big, bold proposals, they are not the only states where important work is being done to improve upside-down state tax systems and raise revenues for emergent and ongoing needs by increasing taxes on rich households. In Maryland, for example, bills have been introduced to apply a 1 percent surcharge on capital gains income, close the carried interest loophole, strengthen the estate tax and modernize income tax brackets. Advocates and lawmakers in Rhode Island are pushing for progressive income tax increases as well. And Massachusetts leaders are attempting to enact a tax on unearned investment income similar to those described above in Connecticut, Maryland, Minnesota and New York.

In these states and others, a key lesson of the pandemic is catching on: our problems did not begin with this crisis and our solutions must look far beyond it.