By: Carl Davis and Richard Phillips

Thank you for the opportunity to testify on the tax policy issues associated with legalized retail marijuana. Our testimony includes five parts:

1. An overview of the marijuana tax rates and structures that exist in the four states (Alaska, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington) where retail marijuana can be legally sold.

2. An analysis of early stage revenue trends in the two states (Colorado and Washington) where legal, taxable sales of retail marijuana have been taking place since 2014.

3. A discussion of issues associated with different types of marijuana tax bases—specifically weight-based taxes, price-based taxes, and hybrids of these two structures.

4. A discussion of issues involved in choosing a tax rate for marijuana.

5. A discussion of long-run issues related to the structure of marijuana taxes and their revenue yield.

Current Approaches to Taxing Retail Marijuana Sales

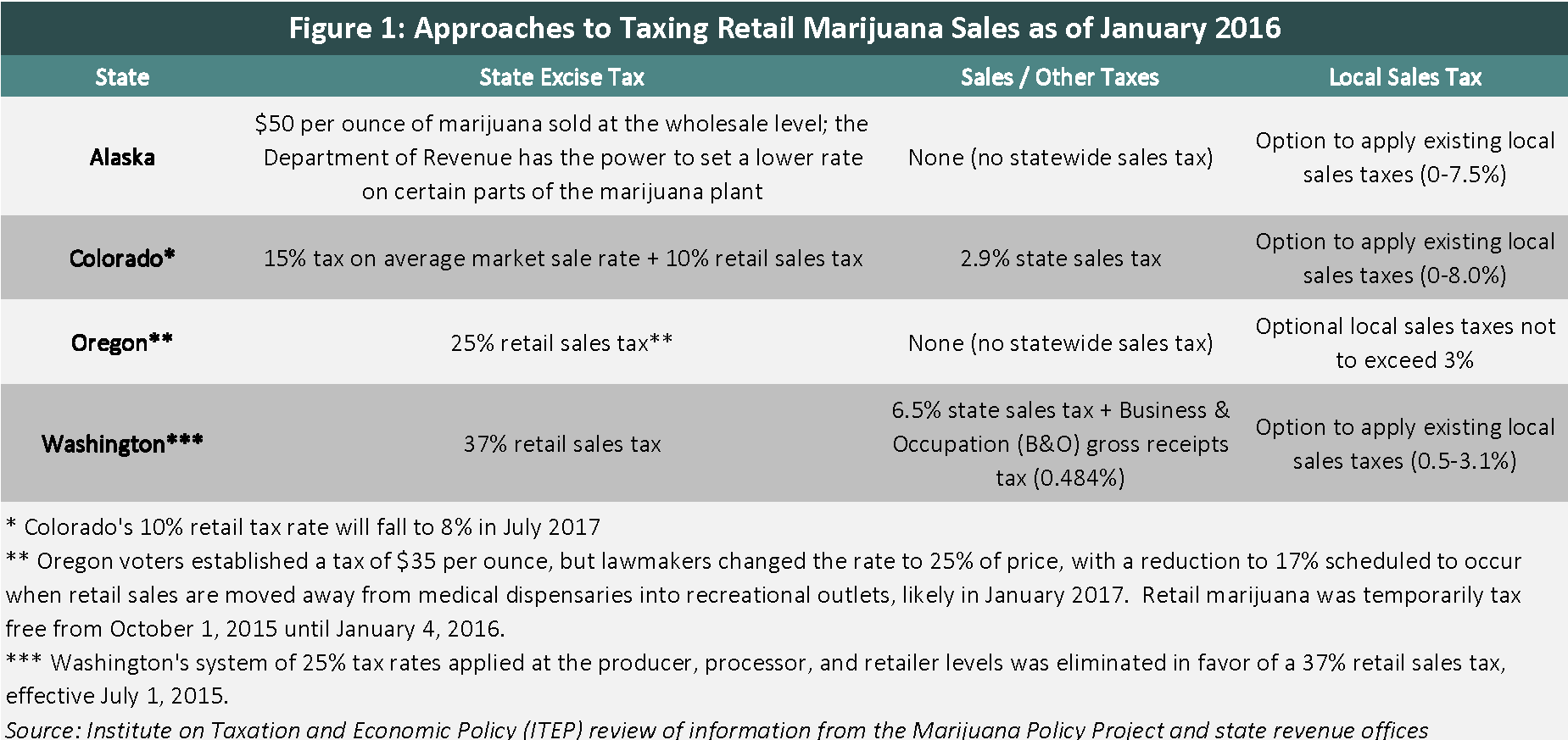

Four states currently allow for taxable retail sales of marijuana under the tax structures identified in Figure 1:

As can be seen from the table, most taxes on retail marijuana are based on the product’s price rather than its weight. The most notable exception is Alaska, which has a $50 per ounce tax on marijuana, though collections under this tax will not begin until late summer, at the earliest, when retailers begin making sales. Additionally, while Colorado’s 15 percent tax is based on the price of marijuana, in practice the Colorado Department of Revenue (CDOR) converts this amount to a weight-based tax that varies periodically using its own calculation of the average market price of marijuana. This is done to improve tax enforcement by avoiding dishonest reporting of “transfer prices” within an integrated business—an issue discussed more below.

All of the excise taxes described above are relatively new (Colorado’s was the first to take effect, in January 2014) and many are subject to ongoing revisions. Washington, for example, recently consolidated three different tiers of 25 percent tax rates into a single 37 percent sales tax rate, in part to reduce the federal tax obligations of marijuana retailers. Colorado will be reducing one of its tax rates by 2 percentage points next year in order to improve the legal market’s competitiveness with the sometimes lower-priced black market. And Oregon, which is temporarily allowing retail sales to take place through medical outlets, plans to reduce its tax rate from 25 to 17 percent once retail outlets are established in 2017. Oregon also previously exempted retail marijuana from the excise tax entirely for the first few months following the start of legal sales.

As seen in Figure 1, the states with legal retail marijuana are largely in agreement that the product should be subject to general sales taxes in addition to standalone excise taxes. Both of the states with broad state-level sales taxes (Colorado and Washington) apply their taxes to retail marijuana and all three states with broad local-level sales taxes (Alaska, Colorado, and Washington) allow their localities to do the same. Alaska lacks any type of broad statewide sales tax, and Oregon lacks both state and local-level sales taxes, though the state will allow its localities to levy special marijuana taxes as high as 3 percent. Given that local sales taxes in Vermont are capped at 1 percent, it seems that Vermont localities under legalization would receive a smaller share of marijuana sales tax revenue than is typical elsewhere unless specific steps are taken to allow for higher local tax rates on marijuana.

Marijuana Revenue Trends in Colorado and Washington

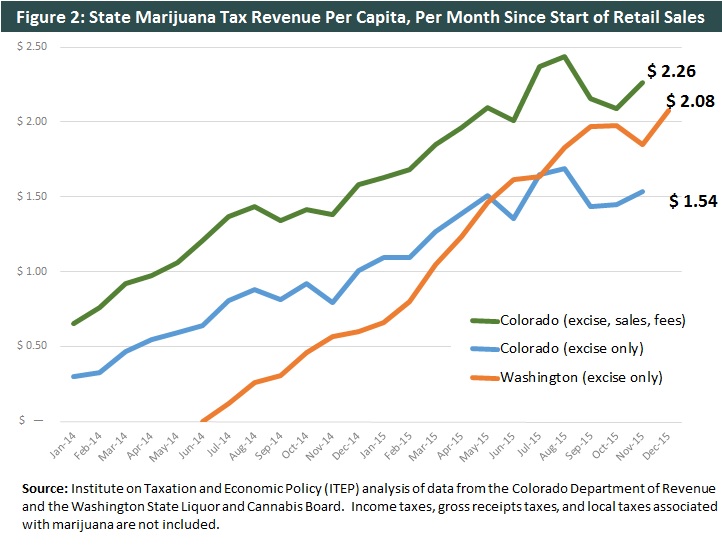

Of the four states where retail marijuana sales are legal and taxable, only Colorado and Washington have been collecting the tax for a sustained period of time (2 years in Colorado and 1.5 years in Washington). In both cases, revenue collections were initially low but grew quickly as the industry became more established.

For the month of November 2015, Colorado collected a total of $12.2 million in excise taxes, sales taxes, and fees from the marijuana industry. This represents 64 percent growth compared to the $7.5 million collection from the same month one year early. Following a relatively slow start to legal sales in Washington, excise tax revenue growth has been even more rapid. Washington’s December 2015 revenue collections of $14.8 million were 246 percent higher than the $4.3 million collected exactly one year earlier.

Figure 2 displays these figures on a per capita basis in order to control for Colorado and Washington’s differing population sizes. As of November 2015 Colorado was collecting $2.26 per month, on a per capita basis, in state-level excise taxes, sales taxes, and fees. Meanwhile, Washington collected $2.08 per month, per capita, in excise taxes alone.

If these most recent revenue figures are held constant for a 12 month period and scaled down to reflect Vermont’s smaller population size, they translate into roughly $11 million to $17 million in revenue per year. In reality, however, the usefulness of these figures for gauging the revenue potential of retail marijuana in Vermont, or even in Colorado and Washington for future years, is extremely limited. For starters, these figures exclude marijuana-related revenue collected via income taxes, gross receipts taxes, and local sales taxes. Even more important are the ongoing changes expected to occur in the price of marijuana, the business practices of legal retailers, the importance of the black market, the use of medical marijuana, the legal status of marijuana in other states, and numerous other factors that are certain to continue driving changes in marijuana tax collections for years to come. Finally, for Vermont in particular there are reasons to expect that factors such as marijuana tourism (2.7 million marijuana users live within 200 miles of Vermont according to the RAND Corporation) and the potential for residents to grow their own marijuana free of taxes (a practice that is illegal in Washington) could result in different revenue levels than have been observed so far in Colorado and Washington.

Tax Base Considerations

If lawmakers agree that retail marijuana sales should be legalized, one of the most fundamental tax policy decisions they must make is whether to base the tax system around the product’s weight, its price, or some combination of these factors. Price-based excise taxes, akin to traditional sales taxes, currently exist in Vermont for products such as chewing tobacco and liquor. By contrast, weight-based (or similar quantity-based) taxes are used by both Vermont and the federal government for cigarettes, and by the federal government for sales of gasoline. Straddling a middle ground between these two options is Vermont’s gasoline tax, which is based primarily on price but has a backstop “floor” in place to prevent the tax from shrinking below a certain per-gallon rate.

Weight-based taxes

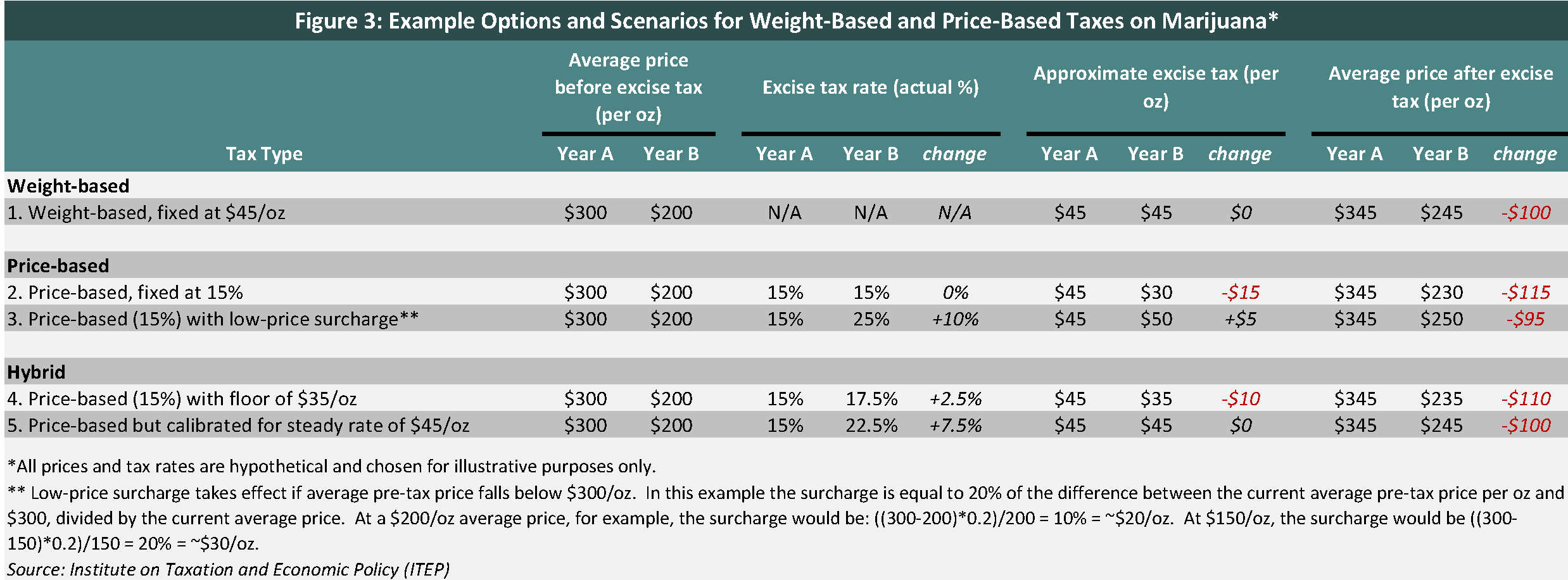

One of the main advantages of weight-based marijuana taxes is that they offer some measure of stability over time. Regardless of what happens to the price of marijuana in the years ahead, Vermont would be guaranteed to collect the same amount per ounce legally sold within the state (see Option 1 in Figure 3, below, for an example). And if that tax amount were written in such a way to allow it to rise alongside inflation (much like the state’s income tax brackets and exemptions), the tax would be somewhat more sustainable over time.

While there are enforcement issues unique to weight-based taxes, these structures are less susceptible to the tax avoidance opportunities afforded by “bundling” and gaming of the “transfer pricing” system—both issues discussed in the next section.

Since weight-based taxes have no ties to the price of marijuana, they are arguably preferable for small-scale, craft businesses because the higher prices these businesses typically need to charge do not result in higher tax payments.

On the other hand, weight-based taxes lack any mechanism for distinguishing between differing potency levels in different strains of marijuana. As a result, a weight-based tax may skew the market somewhat toward high-price, high-potency strains since the additional level of intoxication that these strains provide does not bring with it any additional tax.

Price-based taxes

One of the main advantages of establishing a price-based tax is that it can be administratively simple since it does not require implementation of official standards and methods for verifying the weight of marijuana being sold.

Price-based taxes also offer the advantage of being at least roughly linked to the potency level of marijuana. Under a weight-based tax, large quantities of weak marijuana face a higher tax bill than small amounts of high-potency marijuana—even if the level of intoxication those quantities can provide is roughly similar. In this sense, price-based marijuana taxes are more akin to the current system of taxes on alcohol where liquor tends to be taxed more heavily than beer because of its higher alcohol content. Until reliable methods for directly measuring marijuana potency are developed, price-based taxes will remain the best option available for implementing a higher tax rate on more potent marijuana.

On top of these benefits, there is reason to believe that price-based taxes may also be somewhat less regressive than weight-base taxes. Under a price-based tax, lower-quality marijuana is taxed less heavily than high-end “premium” strains that are more likely to be purchased by households with higher levels of disposable income.

On the other hand, price-based taxes often require that steps be taken to prevent “bundling” and “transfer pricing” schemes. Bundling occurs when retailers offer a marijuana “giveaway” for customers that purchase a different, more lightly taxed product. Under many price-based taxes, gifted marijuana in this scenario would be considered as being sold for $0 and no excise tax would be charged. This outcome can be avoided through anti-bundling laws, though they do add an additional layer of complexity to the tax.

Transfer pricing issues come into play when marijuana is reported to have been transferred between related businesses at an artificially low price. By claiming that wholesale transactions occurred at a very low price, the amount of tax owed under some price-based marijuana taxes can be minimized. This outcome can be avoided by taxing the product only at the point of final retail sale, prohibiting transactions between related businesses, or calculating a market-wide average price to be used when computing the amount of tax owed in any transaction. While these options are all viable solutions to transfer pricing, each brings with it additional complexity.

The most serious shortcoming of price-based taxes, however, is that the future of this tax base (marijuana prices) is highly uncertain. Most analysts expect that the price of marijuana will fall significantly as the industry learns to cut costs and as state and federal legal barriers are gradually repealed. When, and how dramatic, that decline in price will be is far from certain. But if prices decline (or potentially even collapse), most price-based taxes will decline as well. The result could be a drop in dedicated funding for marijuana enforcement and substance abuse programs, as well as in general fund revenues.

Furthermore, as Option 2 in Figure 3 demonstrates, a price-based tax could actually exacerbate a decline in marijuana prices. Under a 15 percent tax, for example, a $100 drop in pre-tax prices per ounce would be magnified to $115 once the associated tax reduction is taken into account. This could be problematic to the extent that lower prices might lead to additional “undesirable” consumption—such as by youths, drugged drivers, or non-residents seeking to divert substantial quantities out of state in violation of federal law.

Notably, however, there are novel price-based options that could actually help counteract any decline in price deemed to be “excessive.” Option 3 (Figure 3) demonstrates one such scenario in which state officials monitor the average price of marijuana and automatically implement a sliding-scale tax rate increase if that price falls below $300 per ounce (for example). In this specific scenario, rather than seeing the tax rate per ounce decline by $15 in the wake of a $100 price drop, the rate would actually rise by $5—a result that would allow for modest growth in tax revenue and, perhaps more importantly, would at least incrementally counteract this dramatic drop in pre-tax prices.

Hybrid taxes

As the above discussion makes clear, there are advantages and disadvantages associated with both weight-based and price-based taxes on marijuana. Given this reality, there is some appeal to a hybrid tax model that incorporates different aspects of these two structures.

The most straightforward hybrid is to base the tax rate primarily on price, but to create a backstop tax “floor” that prevents the tax from falling below a certain level in the event of a price collapse. To do this, state officials would need to monitor the average price of marijuana and be prepared to raise the price-based tax rate if the average tax owed per ounce falls below a pre-specified level. Option 4 (Figure 3) demonstrates this option with a $35 floor on the tax owed per ounce. In this scenario, the tax owed in the event of a $100 price drop would fall by just $10 per ounce, as opposed to the $15 decline exhibited in Option 2. While some of the technical details involved in implementation may differ, Option 4 is fundamentally very similar to the method that Vermont currently uses for taxing motor gasoline.

A slightly more aggressive version of this price floor approach is demonstrated in Option 5 (Figure 3), where officials use tax adjustments not just in the event of a severe tax decline, but rather perform these adjustments on a regular basis in order to target a specific weight-based tax amount at all times. The advantages of this approach are the same as those discussed above in the context of weight-based taxes, with the added simplicity gains associated with not having to strictly monitor the methods and procedures involved in reporting marijuana weights for tax purposes.

Tax Rate Considerations

Regardless of how lawmakers decide to structure a tax on marijuana, they will also need to decide how heavily to tax the product. For any tax, determining the appropriate level of the tax rate requires weighing various, and sometimes competing, considerations. Marijuana taxes are no exception to this rule, though the relative novelty of retail marijuana legalization means that some of the issues involved may be less familiar to lawmakers. What follows is a very brief overview of some of the tradeoffs involved in setting a relatively high, or relatively low, rate of tax.

Advantages of levying a high tax rate on retail marijuana:

- Curbing undesirable consumption: Raising the price of marijuana through higher tax rates (or any mechanism) is likely to reduce marijuana consumption. To the extent that this reduction is accompanied by decreases in behaviors such as drugged driving, or in the rate of use by underage individuals, a higher tax rate could be socially beneficial.

- Avoiding federally prohibited diversions into other states: A higher tax on Vermont marijuana would make it less appealing to residents of nearby states, thereby reducing the likelihood that non-residents would seek to bring significant quantities back to their home states. As long as marijuana remains illegal under federal law, states that have legalized retail marijuana are at risk of federal intervention if they do not take steps to prevent the substance from being diverted to states where it remains illegal. Strict limits on the amount of marijuana that any individual can purchase (especially non-residents) can also help contribute to this goal.

- Funding pubic services: Setting the tax rate high enough to generate significant revenue (though not so high as to leave a large black market intact) would allow for robust investments in marijuana regulation and substance abuse treatment, as well as for additional funding of other public services that could improve the wellbeing of Vermont residents.

Advantages of levying a low tax rate on retail marijuana:

- Shrinking the black market: One primary motivation behind legalizing retail marijuana is to eliminate the illegal black market for marijuana and its associated ills. If legal marijuana is taxed too heavily, however, its high price will incentivize consumers to remain in (or return to) the black market for their marijuana purchases. This consideration is especially important in the early stages of legalization when newly legal retailers are likely to charge higher prices as they grapple with upfront costs, and as the many consumers with well-developed ties to the black market are first confronted with the choice of whether to shift their purchases to the legal market.

- Reducing the incentive for abuse of the medical marijuana system: A high tax rate applied to retail marijuana could drive a wedge between retail and medical marijuana prices if, as seems likely, medical marijuana is not subject to the same level of tax. If significant savings can be realized by making purchases on the medical market, an incentive would be created for consumers that do not actually need marijuana for medical purposes to seek out medical registrations nonetheless. One alternative approach to avoiding this problem is to enforce strict rules regarding who is eligible to purchase from medical suppliers—an approach that currently seems to be in place in Vermont.

- Reducing the incentive for tax evasion: The federal prohibition on marijuana means that retailers generally do not have access to banking services and often operate on a cash-only basis. This reality makes recordkeeping somewhat more difficult and provides an opportunity for unscrupulous retailers to underreport their sales in order to dodge their tax collection responsibilities. A lower tax rate on marijuana would reduce the temptation to do so.

- Nurturing a new industry and its economic potential: As mentioned earlier, marijuana prices are likely to be relatively high at the outset of legalized sales. If those high prices are inflated even further by a high tax rate, the ability for the legal industry to attract customers—both from other states and from the black market—will be curtailed. To the extent that lower marijuana prices could bring customers from out-of-state that might also buy gasoline, restaurant meals, hotel rooms, and other goods and services during their stay, a lower tax rate on marijuana could be economically beneficial. Vermont would need to be careful, however, not to provoke the ire of the federal government by allowing large quantities of marijuana to flow outside of its borders.

Long-Run Tax Structures and Revenues

The legalization of retail marijuana sales in Alaska, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington provides new sources of information for states such as Vermont that are considering doing the same. In regard to the tax policy implications of legal marijuana, however, the rapidly evolving nature of this industry means that many of the lessons being learned about marijuana tax rates, structures, and revenues are likely to become outdated in a relatively short amount of time.

If Vermont lawmakers choose to legalize marijuana sales, they should certainly strive to enact the best possible tax structure based on current information, and they can even plan ahead for future changes in the industry through the use of tax “triggers” (such as a floor on the minimum marijuana tax rate to be used in the event of a price collapse). But no matter how well thought out any marijuana tax may be, it will need to be periodically revisited as changes occur in the price of marijuana, the structure of the industry, marijuana’s legal status at the federal level and in other states, the technologies available for measuring potency, and other factors. In other words, it seems probable that the best possible tax structure for a legal marijuana market in 2017 is going to be quite different from the best possible tax structure in 2027.

For lawmakers that are searching for clues on the long-run trajectory of legal marijuana, the best place to look may be the gambling industry. Early adopters of legal gambling such as Atlantic City initially reaped an enormous economic and tax revenue windfall as gamblers flocked to the city’s casinos. Over time, however, legal gambling has become more widespread and while Atlantic City still enjoys something of a comparative advantage in the industry, that advantage has been significantly reduced with damaging consequences for the city’s economy and its finances.

It is highly unlikely that Vermont will ever be as reliant on marijuana sales as Atlantic City has been on gambling. Nonetheless, if Vermont legalizes marijuana earlier than its neighbors, its initial monopoly on legal sales in the region during these times of relatively high marijuana prices could conceivably create a similar scenario. As prices drop and marijuana production and sales become more evenly distributed across states, however, the advantages of being an early adopter will eventually fade.

Given all of the uncertainties just described, Vermont lawmakers should take care not to allow the state’s finances to become overly dependent on marijuana. The best way to accomplish this is through only very sparing dedications of tax revenue to specific budget areas. Setting aside some amount of marijuana revenue for the administration and enforcement of marijuana laws, and for the treatment of marijuana abuse, is reasonable. Beyond that, however, Vermont would be well served by allowing the remainder of marijuana tax revenue to flow into the general fund where the impacts of its volatility can be muted by other revenue streams.