Preventing an Overload: How Property Tax Circuit Breakers Promote Housing Affordability

reportKey findings

● Circuit breaker credits are the most effective tool available to promote property tax affordability. These policies prevent a property tax “overload” by crediting back property taxes that go beyond a certain share of income. Put another way, circuit breakers intervene to ensure that property taxes do not swallow up an unreasonable portion of qualifying households’ family budgets.

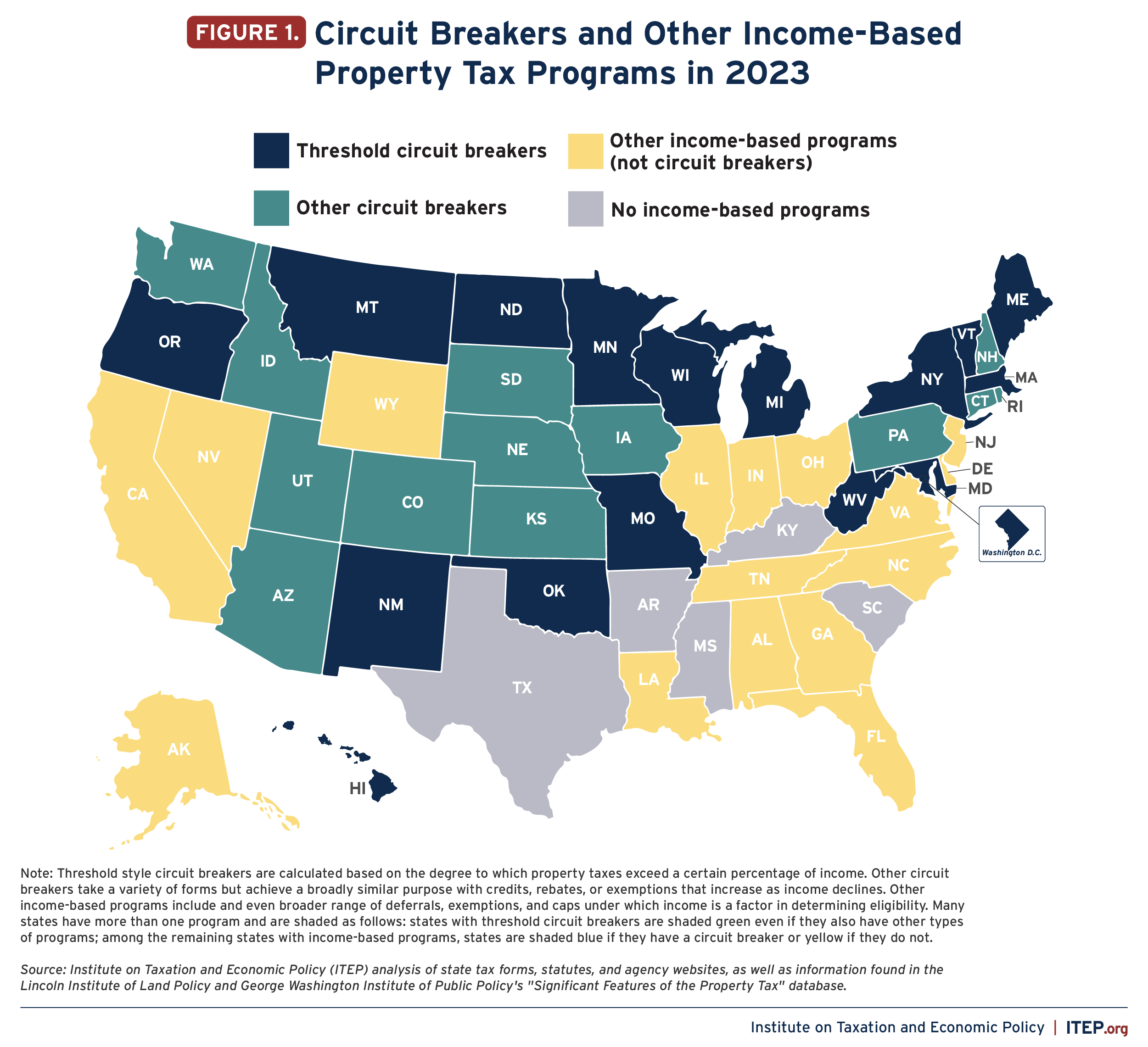

● Most states (29 and the District of Columbia) offer some kind of circuit breaker in 2023, though these policies vary widely in size and scope. Another 16 states offer an income-limited property tax cut that falls short of being a true circuit breaker. Just five states do not offer any kind of income-targeted property tax break at all: Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas.

● Slightly more than half of states with circuit breakers (17 of 30) target property tax cuts exclusively to seniors, on the theory that older taxpayers may have more difficulty affording the property taxes on a home they bought during their prime earning years. But other households are susceptible to a property tax “overload” as well including, for example, people who have recently lost their jobs or who live in gentrifying areas.

● More than two-thirds of states with circuit breakers (21 of 30) extend their programs to at least some renters, and Oregon provides its circuit breaker exclusively to renters. This is important because it is widely understood that owners of rental real estate pass through at least some of their property tax liability to renters through higher rents. Including renters is especially vital to ensuring that people of color can benefit, as centuries of racial exclusion and discrimination have made people of color of all ages much more likely to rent and to work in jobs with lower wages today.

● Circuit breakers are most effective when their benefits are large enough to meaningfully lower property taxes, their eligibility criteria are not overly restrictive, and residents know about them and can easily access them. Robust and well-advertised circuit breakers have immense potential to promote property tax affordability and improve the overall regressive tilt of property tax systems.

Introduction

Concerns over property tax affordability have been used to advance a wide array of property tax cuts such as homestead exemptions, tax rate caps, and limits on growth in assessed value. But no tax cut offers a more targeted solution to property tax affordability problems than circuit breaker credits. This is because circuit breakers are the only tools for reducing property taxes that measure the affordability of property taxes relative to families’ ability to pay.

Circuit breakers protect families from property tax “overload” much like how traditional circuit breakers protect against electrical overload. Under most circuit breaker programs, when a property tax bill exceeds a certain percentage of a taxpayer’s income, the circuit breaker reduces property taxes in excess of this “overload” level.

This report introduces the key problem presented by property taxes, explains how circuit breakers function, summarizes major features of programs across the country and outlines important considerations that policymakers interested in designing or re-designing a credit will confront.

The Main Problem: Property Taxes Are Often Disconnected from Ability to Pay

Residential property taxes are regressive, requiring low-income families to pay more of their income in tax than wealthier families. Nationwide, the poorest 20 percent of taxpayers pay 4.2 percent of their income in property taxes, compared to 3 percent for middle-income taxpayers and 1.7 percent for the wealthiest 1 percent of households, according to ITEP’s most recent comprehensive study of state and local tax codes.[1]

The main reason property taxes are regressive is that home values are much higher, as a share of income, for low-income families than for the wealthy. Making matters worse, home values are often mismeasured, for property tax purposes, in ways that exaggerate this fundamental fact. Specifically, homes owned by lower-income people and people of color tend to be over-assessed relative to those owned by high-income people.[2]

Because property taxes are based on home values rather than income, property taxes are disconnected from “ability to pay” considerations in a way that income taxes are not. This disconnect can create problems for families as their financial circumstances evolve. Someone who suddenly becomes unemployed, for example, will find that their property tax bill is unchanged even though their ability to pay it is greatly reduced.

Senior citizens often find themselves in a similar situation as their incomes in retirement tend to be lower than during their working years, which can make it challenging to afford a property tax bill that they previously paid with ease—especially if their home’s value has increased dramatically since the time of purchase. This is especially true for today’s retirees of color, who often faced workplace discrimination and may have been relegated to lower-paid jobs with limited or non-existent retirement benefits.

People living in gentrifying areas—a disproportionate share of whom are Black or Hispanic—can also be harmed if their home value and property tax bill surges but their annual income does not keep pace.[3]

Property tax affordability is also a problem for renters, as there is wide agreement that landlords pass at least some of their property tax expense along to their tenants. Because renters tend to have lower incomes and lower wealth than homeowners, affordability concerns can be particularly acute for this group.

Types of Circuit Breakers

The basic idea behind the “circuit breaker” approach to reducing property taxes is simple: taxpayers earning below a certain income level should be helped when their property taxes are high relative to their income.

The most common form of help is a threshold-style circuit breaker. Under this approach, credits or rebates are calculated using a formula that compares property tax liability to income and offsets some or all the property tax that exceeds what is designated as unaffordable under the program.[4] In West Virginia, for example, property taxes that exceed 4 percent of income can be credited back to eligible taxpayers (up to a maximum credit of $1,000) as long as income is below $40,770 for single individuals or $54,930 for married couples in 2022.[5]

Not all circuit breakers take this form, however. Researchers at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy have identified a handful of other types of circuit breakers that achieve a broadly similar purpose with somewhat different mechanics. They define circuit breakers to include policies where “direct property tax relief to households … increases as household income declines.”[6] Utah’s program, for instance, provides a credit of $1,186 to households with income below $13,044 in 2023; the credit gradually declines as income rises to a minimum amount of $188 for households with income between $34,352 and $38,369 and is unavailable above that level.[7] While the program does not specifically provide credit for taxes paid above a specific threshold level, the end result looks quite similar.

Some states offer other forms of property tax breaks, aside from circuit breakers, that are restricted to people with incomes below a certain amount. These include programs like homestead exemptions, deferral programs, and assessment limitations. While limiting eligibility based on income adds some measure of ability to pay to the property tax system, these provisions are not as carefully targeted as true circuit breakers.

Circuit Breakers Are Common in the States

Most states offer some kind of property tax circuit breaker, though they vary widely in size and scope. Currently, 29 states and the District of Columbia offer property tax circuit breaker programs.[8] Among these states, 17 plus D.C. use the threshold approach discussed above while 12 states make use of other forms of circuit breakers. Another 16 states do not offer circuit breakers but have at least one other type of income-limited property tax break. Just five states do not offer any kind of income-based property tax break: Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas.

More detail on these programs can be found in Appendices A and B.

Circuit Breakers Improve Property Tax Fairness

Robust circuit breakers are an effective way to lessen the regressive tilt in state and local property tax systems. Figure 2 presents data from the Minnesota Department of Revenue revealing how Minnesota property taxes vary across the income scale.[9] Absent the state’s circuit breaker program, the property tax would be a purely regressive tax: affluent families would pay the least, relative to income, while low-income families would pay the most and middle-income families would fall somewhere in between.

But the property tax offset provided through the state’s circuit breaker program—one of the largest in the country—significantly improves this regressive distribution. After the circuit breaker is included, very low-income families still pay the highest rate but otherwise the property tax is moderately progressive throughout most of the income scale.

At the top of the income distribution, however, the property tax remains somewhat regressive. This finding illustrates that while circuit breakers are well equipped to improve property tax fairness for low- and middle-income families, ending property tax regressivity at the top of the income scale is better accomplished through raising property tax rates on high-value properties with a tiered real estate property tax and real estate transfer tax.[10]

Designing Effective Circuit Breakers

A circuit breaker vs. income-only approach is just one of many decisions state policymakers must consider when implementing a circuit breaker. Other questions include:

Should the credit be available only to senior citizens or to taxpayers of all ages?

Slightly more than half the states with circuit breakers (17 of 30) target property tax cuts exclusively to seniors. This is usually based on the perception that these taxpayers have less ability to pay taxes due to having lower incomes than in their prime earning years when they likely purchased their homes.[11] But other households can be susceptible to property tax “overload” including, for example, people who have recently lost their jobs or who live in gentrifying areas. Thirteen states make their circuit breaker programs available to non-senior homeowners, including the larger and more consequential programs available in states such as Michigan and Minnesota.

Should the credit be limited to homeowners, or extended to renters as well?

It is widely accepted that owners of rental real estate pass at least some of their property tax liability along to renters through higher rents. Because of this, more than two-thirds of states with circuit breakers (21 of 30) extend their programs to at least some renters, and Oregon provides its circuit breaker exclusively to renters. Extending these programs to renters is especially vital to ensuring that people of color can access their benefits, as centuries of racial exclusion and discrimination have resulted in people of color in all age cohorts being much more likely to rent and to work in jobs with lower wages.

What should be the maximum income level for eligibility?

Income eligibility for circuit breakers varies widely across states. In 2022, income limits on state circuit breakers ranged from $5,501 in Arizona to $134,800 in Vermont. Some states further restrict eligibility based not just on income, but on families’ overall wealth holdings or the assessed value of the home. Many states extend eligibility only to the very poorest families both because this group is most likely to struggle with high property tax bills (or rent) and because extending the credits higher up the income scale can significantly increase their overall cost. Property tax affordability can also be a problem for middle-income families, however, making it worthwhile to find a way to include them. States with income eligibility ceilings above $50,000 include Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Vermont, and West Virginia.[12]

What cap should be imposed on the credit?

Circuit breakers typically include a cap on the maximum size of the tax break that any individual or family can receive.[13] Most programs cap the annual tax cut at between $200 and $1,500 per family, though there are states with higher and lower caps. Minnesota, for example, caps its homeowner circuit breaker at $3,140 in 2022 and Vermont caps the combined benefit of two of its programs at $8,000. Caps can ensure that wealthy families living in very valuable homes do not receive exceptionally large credits simply because their income is low in a given year. They can also constrain the cost to state budgets. Setting the cap too low, however, risks undermining how well the programs improve property tax affordability.

Should the maximum income level, or the maximum credit, be indexed to inflation?

Failing to tie the value of the credit to inflation will reduce the real value of the credit each year. Indexing income limits (and the maximum credit amount) to inflation helps ensure that circuit breakers continue to provide meaningful benefits in the long run. Many states have unintentionally allowed the value of their circuit breakers to decline over time by ignoring the impact of inflation.[14]

What percentage of income should be considered an “overloaded” property tax bill?

Under threshold-style circuit breakers, lawmakers must decide what level of property tax, relative to income, is considered reasonable. Typically, states choose a figure in the single digits. In West Virginia, for example, taxpayers can only claim the credit if their property taxes exceed 4 percent of their income while in Maine the threshold is 6 percent. Many states vary their thresholds by income level such that lower-income families see a lower threshold than middle-income families because even modest property tax bills can be difficult for low-income families to afford.

How to best administer the credit?

States vary in their administration of circuit breaker programs, with approaches ranging from standalone rebates to administration through property tax or income tax systems. In states with income taxes, the option to claim these credits through the personal income tax likely increases their reach as most families file income tax returns. However, people who don’t meet the requirements to file an income tax return—like senior citizens with nontaxable retirement income, for example—should be offered the chance to claim the credit as a standalone rebate instead as they still pay property taxes and other state and local levies.[15] In states without income taxes, the program must be administered either as a standalone rebate or by allowing taxpayers to submit eligibility information to their local property tax office in advance of the mailing of property tax bills.[16]

How can homeowners and renters be made aware of these programs?

The main drawback of circuit breakers is that, in general, they are only given to taxpayers who apply for them (by contrast, general “homestead exemptions” are often given automatically). Eligible taxpayers will, of course, only apply for circuit breaker credits if they are aware of their existence. In some states it appears that many, or even most, eligible taxpayers are unaware of these programs. Public announcements and well-placed advertisements by government agencies and nonprofits can make a difference. Simplifying the claims process and enacting robust credits that are worth the time and effort to claim also increase uptake. To reach more eligible taxpayers, states may want to look into ways to partially automate the circuit breaker claims process through innovative matching of income and property tax data.

Circuit Breakers Stand Apart

Circuit breakers are the only type of property tax cut explicitly designed to reduce the property tax load on those most affected by the tax. For lawmakers concerned about families facing unaffordable property tax bills, there is no better solution than circuit breakers.

Homestead exemptions, by contrast, exempt a certain portion of home value from tax and are less squarely focused on the issue of property tax affordability since they usually provide benefits to all homeowners regardless of need.[17] When the exemption is provided as a flat dollar amount, for example, homes worth $200,000 receive the same tax benefit as homes worth $20 million. Percentage-based exemptions are even less equitable, as high-value homes receive the largest benefits.

Capping growth in assessed value misses the mark by an even wider margin and these policies tend to favor wealthier people living in high-value homes that are appreciating quickly in value.[18] Young families seeking to buy their first home fare particularly poorly under assessment caps because artificially holding down the property tax bills of long-time homeowners pushes more of the responsibility for funding local services onto new buyers.

Unlike tax caps or homestead exemptions, circuit breakers undertake a direct measurement of each family’s ability to pay property tax—as measured by their income—and calibrate the credit or rebate to ensure that their final net tax bill is affordable. This sharp precision in measuring what constitutes an affordable property tax bill also helps to hold down the cost of circuit breakers relative to more sweeping, less targeted alternatives.

Overall, circuit breakers are an attractive approach to reducing property taxes because they are laser-focused on promoting property tax affordability. These policies can be far less costly than other tax cut options like assessment limitations or homestead exemptions and can meaningfully move the needle in improving the overall fairness of the property tax. A well-designed circuit breaker, paired with a robust outreach strategy to make its benefits known, offers a valuable tool for lawmakers seeking to lessen the property tax load on their most vulnerable residents without drastically reducing the state revenues necessary to fund public services.

Endnotes

[1] Meg Wiehe, Aidan Davis, Carl Davis, et al., “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. October 2018. https://itep.org/whopays/.

[2] Christopher Berry, “Reassessing the Property Tax.” February 2021. https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/6/2330/files/2019/04/Berry-Reassessing-the-Property-Tax-2_7_21.pdf. Carlos Avenancio-León and Troup Howard, “The Assessment Gap: Racial Inequalities in Property Taxation,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth. June 2020.

[3] David Crawford, “Gentrification and the Property Tax: How Circuit Breakers Can Help,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, April 2021. https://itep.org/gentrification-and-the-property-tax-how-circuit-breakers-can-help/.

[4] Credits are typically administered via the personal income tax for reasons of administrative simplicity despite the fact that they are intended as property tax cuts. Rebates, by contrast, are administered as standalone programs. A small number of circuit breaker programs are structured as exemptions rather than credits or rebates.

[5] The income cutoff is based on the number of people in the household. These are the amounts for homes with one or two people. Larger households enjoy higher income cutoffs. More detail can be found at: West Virginia Tax Division, “Senior Citizens,” Accessed May 1, 2023. https://tax.wv.gov/Individuals/SeniorCitizens/Pages/SeniorCitizensTaxCredit.aspx.

[6] A thorough discussion of this definition and description of various circuit breaker types can be found in: John H. Bowman, Daphne A. Kenyon, Adam Langley, and Bethany P. Paquin, “Property Tax Circuit Breakers: Fair and Cost-Effective Relief for Taxpayers,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. May 2009. https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/property-tax-circuit-breakers. For a more recent accounting of circuit breakers using the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy’s definition, see the following database: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and George Washington Institute of Public Policy, “Significant Features of the Property Tax, Residential Property Tax Relief Programs,” Accessed May 1, 2023, https://www.lincolninst.edu/research-data/data-toolkits/significant-features-property-tax/access-property-tax-database/residential-property-tax-relief-programs.

[7] Salt Lake County Treasurer, “Circuit Breaker Tax Abatement,” Accessed May 1, 2023. https://slco.org/treasurer/tax-relief/circuit-breaker/.

[8] Previous ITEP publications included a lower count of states with circuit breakers because they focused only on the traditional “threshold” style programs. This report adopts a more expansive definition more closely in line with the one used by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

[9] Minnesota Department of Revenue Tax Research Division, “2021 Minnesota Tax Incidence Study: An Analysis of Minnesota’s Household and Business Taxes,” March 2021. https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/2022-07/2021%20Tax%20Incidence%20Study.pdf.

[10] Michael Leachman and Samantha Waxman, “State ‘Mansion Taxes’ on Very Expensive Homes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. October 2019. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-mansion-taxes-on-very-expensive-homes.

[11] Younger disabled people are also often eligible for circuit breaker programs.

[12] ITEP analysis of the information found in the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and George Washington Institute of Public Policy’s “Significant Features of the Property Tax” database, as well as information from state tax agencies. Note that Hawaii’s circuit breakers are administered at the local level rather than the state level.

[13] This is usually accomplished by directly capping each family’s maximum tax savings, though sometimes caps are structured such that only a portion of each home’s value qualifies for the program.

[14] Dylan Grundman O’Neill, “Indexing Income Taxes for Inflation: Why It Matters,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, August 2016. https://itep.org/indexing-income-taxes-for-inflation-why-it-matters-1/.

[15] ITEP’s comprehensive analysis of state and local taxes can be found at: Meg Wiehe, Aidan Davis, Carl Davis, et al., “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. October 2018. https://itep.org/whopays/.

[16] A helpful discussion of administrative options is available in Chapter 6 of: John H. Bowman, Daphne A. Kenyon, Adam Langley, and Bethany P. Paquin, “Property Tax Circuit Breakers: Fair and Cost-Effective Relief for Taxpayers,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. May 2009. https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/property-tax-circuit-breakers.

[17] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Property Tax Homestead Exemptions,” September 2011. https://itep.org/property-tax-homestead-exemptions/.

[18] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Capping Property Taxes: A Primer,” September 2011. https://itep.org/capping-property-taxes-a-primer/.