The Trump-GOP Tax Law Encourages Corporations to Move Profits Offshore

The nation’s corporate tax system has been dysfunctional for decades. Unfortunately, the recently enacted Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) fails to solve fundamental problems facing the corporate tax and, in some ways, makes these problems even worse.

Congress could have fixed many problems by following one simple principle: tax offshore profits of American companies the same way their domestic profits are taxed. The old system was problematic because it allowed American corporations to “defer” paying U.S. taxes on offshore profits until those profits were officially brought to the United States. The new system, under TCJA, is problematic because it taxes offshore profits at lower rates than domestic profits. Both approaches tax profits that are reportedly earned offshore more lightly than domestic profits. Both approaches encourage American corporations to use accounting gimmicks to make profits earned in the United States appear to be earned in tax havens — countries where they will barely be taxed or not taxed at all.

The new law is certainly different from the old law and likely will make some types of corporate tax dodging more common and others less common over time. Whereas the old law encouraged corporations to use accounting schemes to make profits appear to be earned offshore, the new law may encourage corporations to transfer real investments — and jobs and the profits they generate — offshore. To understand why requires some explanation of how the corporate tax rules work now.

GILTI — TCJA’s Weak Attempt to Tax Offshore Profits

Under TCJA, some offshore profits of American corporations are effectively subject to a federal tax rate of zero percent. That’s because the new rules do not tax offshore profits at all unless they exceed an amount equal to 10 percent of the value of the corporation’s tangible assets invested offshore. Tangible assets are what most people think of as “real” investments, such as machines, factories, and stores.

The rules simply assume that offshore profits exceeding 10 percent of these assets are profits from other types of assets (intangible assets like patents) that are easier to shift abroad. The rules call these profits Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI), which may be subject to tax, depending on whether they have been subject to foreign taxes.

The big problem with this is that it means a corporation can lower its share of offshore income that is subject to tax (lower its GILTI amount) by moving more tangible assets abroad. Suppose an American corporation has one offshore subsidiary, which is in the United Kingdom. The American corporation has a factory in the United States that makes goods that are transferred to the offshore subsidiary, which then sells the goods to people in the United Kingdom. The UK subsidiary may have few tangible assets – maybe some stores and an office building. The UK profits exceeding 10 percent of the value of the tangible assets in the United Kingdom are potentially GILTI, subject to U.S. taxes.

But the corporation could reduce or even zero out its GILTI tax by moving the factory and all its machines to the United Kingdom, increasing the amount of tangible assets held offshore. This would make a smaller share of the UK profits (or perhaps none at all) exceed 10 percent of the company’s tangible assets held offshore. A smaller share of the company’s offshore profits is GILTI and potentially subject to U.S. taxes.

Most examples of abuses under the old tax system involved accounting gimmicks that corporations used to make their profits appear to be earned in tax havens. The new rules are worse because they encourage American companies to shift real investments like factories — and the jobs that go with them — offshore.

Of course, some corporations will still use accounting gimmicks to shift profits offshore. Under TCJA, even when offshore profits are identified as GILTI and subject to U.S. taxes, they are effectively taxed at 10.5 percent, which is just half of the 21 percent imposed on domestic corporate profits. In other words, TCJA always rewards corporations that can transform U.S. profits into foreign profits, whether this means shifting profits around on paper or moving actual business operations.

Several of TCJA’s provisions are considered “carrots and sticks” to keep companies from taking domestic profits and disguising them as foreign profits through accounting gimmickry. The GILTI rules are usually described as one of the “sticks” because they will sometimes impose tax on profits shifted offshore. But given the generous exemption equal to 10 percent of tangible assets and the lower rate imposed on profits beyond that amount, GILTI seems like more like a very thin reed than a threatening stick.

The FDII Deduction — A New Tax Break Likely to Violate International Trade Law

One of the TCJA provisions that is considered a “carrot” is a new tax break for income that TCJA calls Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII). The idea is that income that companies earn from intangible assets like patents and copyrights is particularly easy to shift offshore. The drafters thought they could deal with this by allowing American corporations a deduction when such assets are held in the United States and generate income (like royalties) from foreign customers.

But the FDII deduction has the same problem as GILTI. The new law defines FDII simply as profits in the United States from selling to foreign markets minus an amount equal to 10 percent of the value of tangible assets held in the United States. The reasoning is that any profits beyond this amount must be from intangible assets, but that is not necessarily true. (The 10 percent threshold is arbitrary.) Like the GILTI rules, the FDII rules could encourage American corporations to shift real assets (and the jobs that go with them) offshore. In this case, corporations would do this to increase the amount of income that is considered FDII and thus eligible for the FDII deduction.

The FDII deduction also violates international law. FDII is not defined to include any specific type of income but rather subsidizes profits that companies generate from exports. Such export subsidies are banned under the international agreements of the World Trade Organization. The best that can be hoped for is that companies will largely ignore the FDII deduction because they know that the WTO may pressure Congress to repeal it.

The BEAT — A Good Idea That Needs to Be Stronger

One of TCJA’s sticks is what the law calls its Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT). The BEAT is a type of alternative minimum tax. Its rate is just 10 percent, which is far lower than the 21 percent that generally applies to domestic profits. But the income subject to the BEAT is defined to include several types of payments to offshore entities that are not taxable under the regular corporate tax, like payments of royalties or interest to related offshore entities. The idea behind the BEAT is a good one because these payments are often schemes to strip earnings out of the United States.

For example, imagine that an American corporation is a subsidiary of a foreign parent corporation and arranges to sell a patent (at a very low price) to the parent company and then pay royalties (at a high price) to use that patent in the United States. The U.S. operations may be very lucrative, but the U.S. subsidiary makes large royalty payments to the foreign parent company, leaving no U.S. profits to report to the IRS.

Given that the foreign parent company and the American subsidiary are really owned by the same people and operating as one company, the “sale” of the patent and the “royalties” are really accounting fictions that move money around on paper and serve no purpose other than to reduce the U.S. tax bill.

The BEAT, in theory, could discourage this sort of scheme by making certain payments, like the royalties in this example, taxable when they are made to a related foreign company. But the BEAT is unlikely to be strong enough, and it certainly does not solve any problems created by the GILTI and FDII rules.

For one thing, the BEAT does not apply to payments that are embedded in the cost of goods. In the example above, the U.S. subsidiary may be paying its foreign parent company for use of the patent and also for actual goods that it will then sell to U.S. customers. To avoid the BEAT, the company can eliminate the royalty altogether and simply roll that cost into the price of the goods sold from the foreign parent company to the US subsidiary.

The Foreign Tax Credit — A Key Feature of the Tax Code that TCJA Failed to Fix

An ideal tax system would fix these problems and require American corporations to pay the same tax on offshore profits as they pay on domestic profits. But that does not mean that offshore profits would be double taxed. Under the old law and under the new law, when American corporations pay U.S. taxes on their offshore profits, their U.S. taxes are reduced by an amount equal to whatever corporate taxes it paid to foreign governments on those profits.

This is the foreign tax credit (FTC), which is designed to prevent double taxation and would continue to serve that roll in a tax system where offshore profits are taxed just like domestic profits.

For example, assume that Congress changes the law to apply the same 21 percent corporate tax rate to both domestic and offshore profits. If a company earned profits in a country where they were taxed at a rate of just 10 percent, the U.S. tax rate on those profits would be 11 percent, which is the current rate of 21 percent minus the 10 percent paid in foreign taxes.

The problem with the FTC (under the old law and the new law) is that nothing prevents corporations from using excess credits generated by profits in higher-tax countries from offsetting U.S. taxes that are due on profits in lower-tax countries.

For example, if an American corporation earns profits in France and pays the full tax rate in that country, which is about 33 percent, the foreign tax credits claimed for taxes paid to France would exceed what the corporation needs to completely offset US taxes on that income. The company is allowed, under the rules, to use the excess foreign tax credits to reduce its U.S. taxes on profits generated in other countries, including tax havens that impose no tax at all.

The TCJA does create a new limit on foreign tax credits by restricting them to just 80 percent of foreign taxes paid. (The old law allowed corporations to claim FTCs equal to 100 percent of foreign taxes they paid.) But this does not address the problem at all. The limit is applied in all situations, including those in which the FTC is not being abused in any way. At the same time, this limit is too weak to address the real problem, which is cross-crediting by corporations that have subsidiaries in both tax havens with little or no corporate taxes and in normal countries with higher corporate tax rates.

TCJA’s failure to ban cross-crediting of the FTC has significantly weakened provisions like the GILTI rules that were supposed to put a break on corporations shifting profits and jobs offshore.

Other Issues

Most problems with the international corporate tax system under TCJA would be resolved if Congress addressed the issues already described. But some additional problems also warrant attention.

Inversions

Corporations do not stop at using gimmicks to make their domestic profits appear to be earned offshore. Some go even further by using gimmicks to characterize themselves as foreign corporations for tax purposes even though they are truly American companies in almost every way imaginable. In these “inversions,” the American corporation will merge with a foreign one and declare itself to be a foreign corporation, even though the ownership is mostly unchanged. (The majority of the shares of the new entity are owned by the shareholders of the American partner to the merger.) The company can even be managed from the United States.

Corporate inversions have faded from the headlines recently, but there may still be some incentive for companies to use them. Congress can block them by simply requiring any corporation that results from such a merger be treated as American if the ownership is mostly unchanged or the company is managed in the United States. This is particularly important if Congress addresses other problems described in this report. For example, if Congress replaces the GILTI rules with a requirement that offshore profits be taxed the same as domestic profits, more corporations will use the inversion loophole if Congress does not close it.

Transparency

Publicly traded corporations are supposed to disclose information that makes it possible for investors to make informed decisions, and yet corporations reveal very little about how much they earn and pay in taxes in various countries, including in tax havens. Given that corporations are granted privileges like limited liability under law, it would make sense for lawmakers and the public to demand the disclosure of some basic information about companies’ offshore dealings.

It is difficult for investors, journalists, members of the public or even lawmakers to understand what any corporation is doing offshore, including both real profit-making investments and tax avoidance schemes. The U.S. should join the international movement to require country-by-country reporting by corporations of their revenue, profits, taxes, employees, assets and other key metrics.

Legislation to Address the Problems with TCJA’s International Corporate Rules

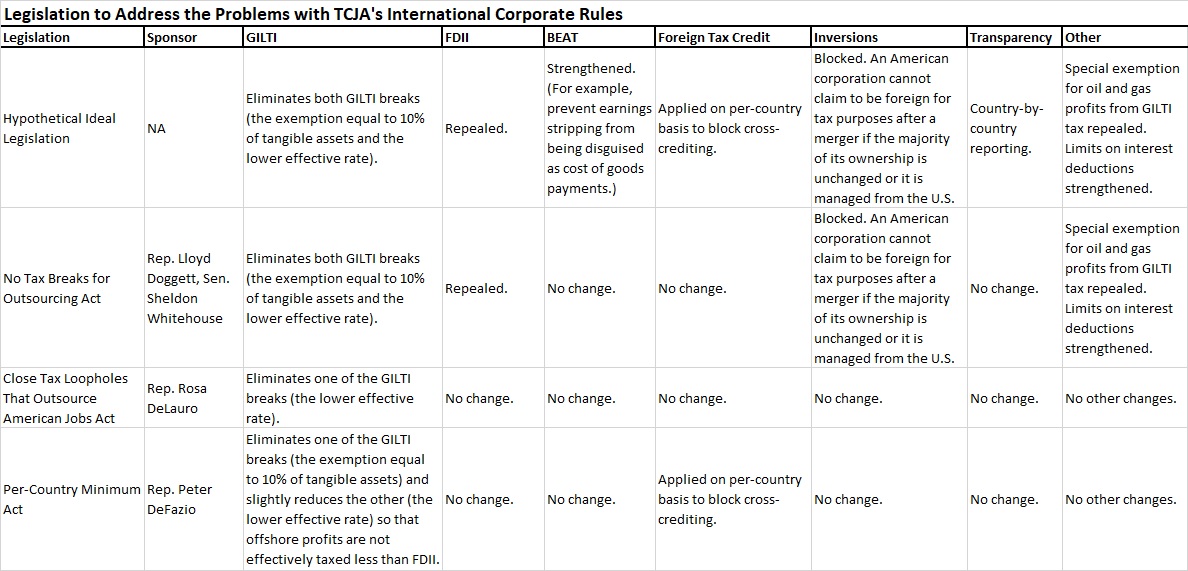

The table below illustrates how Congress would, ideally, craft a bill to address the problems described here and compares that to bills that have been drafted so far. The three bills go a long way to solving some serious problems, but each bill leaves more to be done.