Updated November 16, 2016

INTRODUCTION

The concept of taxing sodas and other sugary beverages has gained traction recently across the United States and around the world. The World Health Organization officially recommended a tax on sugar sweetened beverages as a way to battle the obesity epidemic.[1] In the US, multiple states and localities have looked to taxes on sugar sweetened beverages as a way to improve public health and increase revenue. In 2014, Berkeley, California became the first U.S. locality to enact such a tax. In 2016, similar taxes were enacted in Boulder, Colorado; Albany, Oakland, and San Francisco, California; Cook County, Illinois; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

| What are Sugar Sweetened Beverages?

Sugar sweetened beverages generally include sodas, sports drinks, iced teas, juices, vitamin waters, and energy drinks with added sugar. Beverages with naturally occurring sugars, such as milk and many fruit juices, are not considered sugar sweetened beverages. Most taxes on sugar sweetened beverages also exempt baby formula, meal replacement beverages, beverages taken for medical reasons, and alcohol which is generally subject to a separate tax. Since soda is the most common drink in this category, and the most often discussed, we use the terms “soda tax” and “sugar sweetened beverage tax” interchangeably. |

Proponents of taxes on sugar sweetened beverages cite the potential benefits to public health of reduced sugar consumption and the ability of these taxes to generate meaningful revenue. Opponents note the disproportionate impact that soda taxes have on low-income families (who tend to consume more soda than average), and the fact that soda taxes may not be a sustainable source of public revenue in the long run.

This brief describes various types of taxes on sugar sweetened beverages; surveys where such taxes have been implemented or considered; and reviews the advantages and disadvantages of these taxes.

Sales and Excise Taxes

A tax on sodas and other sugar sweetened beverages can be imposed as part of a broad general sales tax, or as a special excise tax applied only to these specific products.

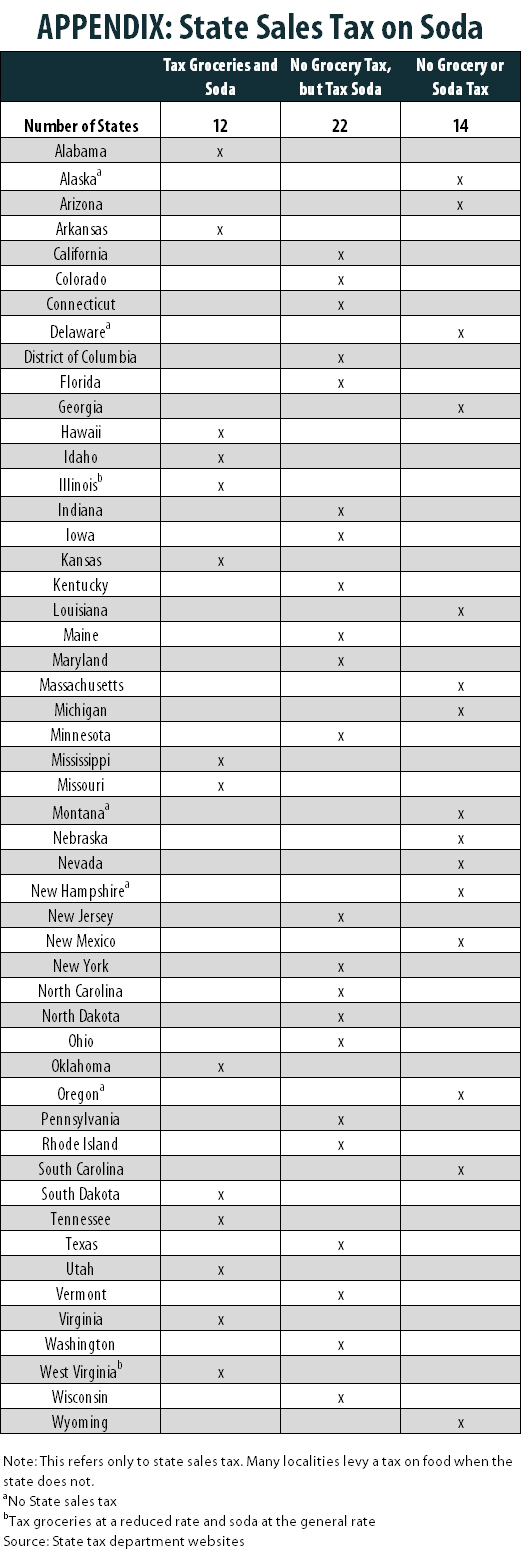

Most states do not tax groceries, but most do apply their sales tax to soda (see Appendix).[2] As of 2016, state general sales tax rates ranged from 2.9 to 7.5 percent of the purchase price, though local sales taxes are added to those levies in 38 states and can sometimes push the actual tax rate to 10 percent or more.[3] Under a fairly typical 7 percent general sales tax, the effective tax rate per ounce of soda might vary from 0.19 cents (on a 33 cent can purchased as part of a 12 pack) to 0.58 cents (on the purchase of a single can at a price of $1).

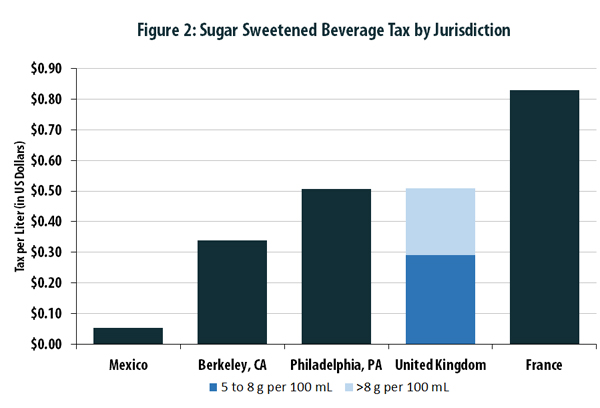

In most cases, however, the term “soda tax” refers not to general sales tax but to a special excise tax on soda and other sugary beverages based on sugar content. Tennessee and Virginia levy a gross receipts tax on manufacturers and distributers of sodas, and Arkansas and West Virginia currently apply an excise tax to sodas and other bottled beverages.[4] These taxes are not based on sugar content and are not shown to have public health effects similar to an excise tax targeted to sugar sweetened beverages. Excise taxes are based on quantity rather than price. With regard to soda taxes, excise taxes also typically happen to be levied at a higher rate than sales taxes. The only two sugar sweetened beverage taxes enacted in the US are currently set at 1 cent per ounce in Berkeley, California and 1.5 cents per ounce in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Soda Tax Design

An excise tax is better than a sales tax at targeting sugar consumption in a uniform fashion. While soda drinkers can reduce the amount of sales tax paid per ounce by buying in bulk, purchasing a less expensive brand, or refraining from ordering pricey sodas at restaurants, an excise tax will tax one ounce of a sugar sweetened beverage at the same rate, no matter its price.

Excise taxes may also be better suited to curbing consumption since they are generally reflected in the sticker price of products. Sales taxes, by contrast, only appear as a line item at the bottom of the customer’s receipt after the purchase has already been completed. This difference arises from the fact that excise taxes are levied on producers rather than consumers, and thus the degree to which retailers pass the tax on to consumers is reflected in the advertised price. On the other hand, if retailers do not pass the full tax on to consumers, then the incentive to purchase fewer sugary beverages may be weakened.

Flat excise taxes are not necessarily well-calibrated to the amount of sugar consumed, however. Berkeley’s excise tax of 1 cent per ounce, for example, treats an 8-ounce can of iced tea with 13 grams of sugar in exactly the same way as an 8-ounce can of soda with 39 grams of sugar. The price effects of this tax may encourage consumers to downsize from a large sweetened beverage to a smaller size. But they offer no incentive to switch from a heavily sweetened beverage (soda) to one with less sugar (iced tea).

The more finely-tuned excise tax enacted in the United Kingdom, by contrast, targets sugar consumption more precisely by levying different tiers of tax based on the amount of added sugars in a beverage. If a primary policy goal of a tax on sugar sweetened beverages is to reduce sugar consumption, then an excise tax based on the amount of sugar would be more effective than one based on either the volume of the beverage or the price paid by the consumer.

Improved Public Health: Arguments in favor of a tax

Most advocates are pursuing taxes on sugar sweetened beverages primarily to improve public health. Obesity has been defined as an epidemic by the World Health Organization, and consumption of sugar sweetened beverages has been linked to increased rates of obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay.[5] A tax on sugar sweetened beverages, at the right level, can curb consumption. Excess caloric intake contributes to obesity and sugary drinks are a source of “empty” calories because they lack significant nutritious content. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages is particularly prevalent in low-income communities and communities of color which also have higher rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

As beverage companies are quick to point out, sugary drinks only represent a small portion of a person’s total caloric intake. But targeting drinks with high amounts of sugar, rather than other high calorie junk food or all products with sugar, is a valid tactic because sugar in liquids is digested by the body differently than sugar in foods. Whereas a sugary food such as a candy bar would take about an hour to digest, the sugar in a drink is absorbed by the body in about half that time.[6] Further, targeting sugar rather than all high-calorie foods is important in the fight against obesity because sugar is converted to fat which leads to weight gain. And sugary drinks are worthy of particular attention because soda accounts for half of the sugar in the food supply even though sodas only represent about 10 percent of the average person’s caloric intake.[7]

Economic theory and some initial evidence suggest that a tax on sugar sweetened beverages is an effective way to reduce sugar consumption. Generally, when prices increase demand for a product decreases. A 2014 study found that a tax of 0.04 cents per calorie, or about 6 cents per 12-ounce can, could lead some consumers to drink 5,800 fewer calories per year.[8] Evidence from Mexico showed a significant reduction in consumption for low-income individuals after that country’s tax was implemented. This suggests the tax may have the desired health effects because low-income Mexicans are particularly likely to be affected by untreated diabetes.[9]

The public health rationale for taxing drinks with added sugar is more apparent than the rationale for taxing beverages with artificial sweeteners, like diet sodas, as Philadelphia and France have done. But there is some evidence that diet sodas may also contribute to obesity-related conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and stroke.[10]

Uncertain Outcomes and Paternalism: Arguments in opposition of a tax

The link between sugary drink consumption and obesity and other negative health outcomes is not as strong as the link, for example, between tobacco products and cancer. Many other factors contribute to an individual’s likelihood of being obese or developing diabetes such as family history, physical activity, and overall diet.[11] Further research still needs to be done on the long-term health impacts of reduced consumption of sugar sweetened beverages. Since soda taxes are a relatively new phenomenon, for now, researchers can only assume that reduced consumption will eventually lead to improved health outcomes. While taxing sugary drinks may reduce consumption of those beverages, some consumers may simply shift to other high sugar, high calorie foods.

Furthermore, even if reducing sugary drink consumption has positive health effects it is unclear if a tax is the best way to achieve this goal. For the jurisdictions that have implemented a tax, it is yet to be seen whether initial rates of decreased consumption will be maintained. Consumers may change their behaviors in response to the initial price hike or the public health education associated with passing these initiatives, but it is unclear if consumption will continue to decrease, stay the same, or possibly even rebound to pre-tax levels. The size and location of the locality implementing the tax also impacts its effectiveness. If consumers can easily shop in another jurisdiction without the tax, the desired impacts on public health and public revenues may not be realized.

Finally, some may view a soda tax as a type of government overreach — an undue infringement on consumers’ food and beverage choices. Unlike the effects of cigarette smoke which can impact non-smokers, the health effects of obesity and diabetes are mostly felt by the individual. There is a public health rationale, however, for combatting obesity because of the associated health care costs that strain publicly funded insurance programs. There is also some concern that if governments begin to subject sugar sweetened beverages to “sin taxes,” other unhealthy food contents like fats or salt may be next.[12]

A Regressive Tax

A tax on sugar sweetened beverages, like most consumption taxes, is regressive. This means that low-income individuals will pay a larger share of their income in the tax than higher earners.

A tax on sugar sweetened beverages, like most consumption taxes, is regressive. This means that low-income individuals will pay a larger share of their income in the tax than higher earners.

An excise tax on sugary drinks is more regressive than most consumption taxes in part because it is based on quantity rather than price. Purchasers of cheaper generic brands incur the same tax as those who buy more expensive brands.

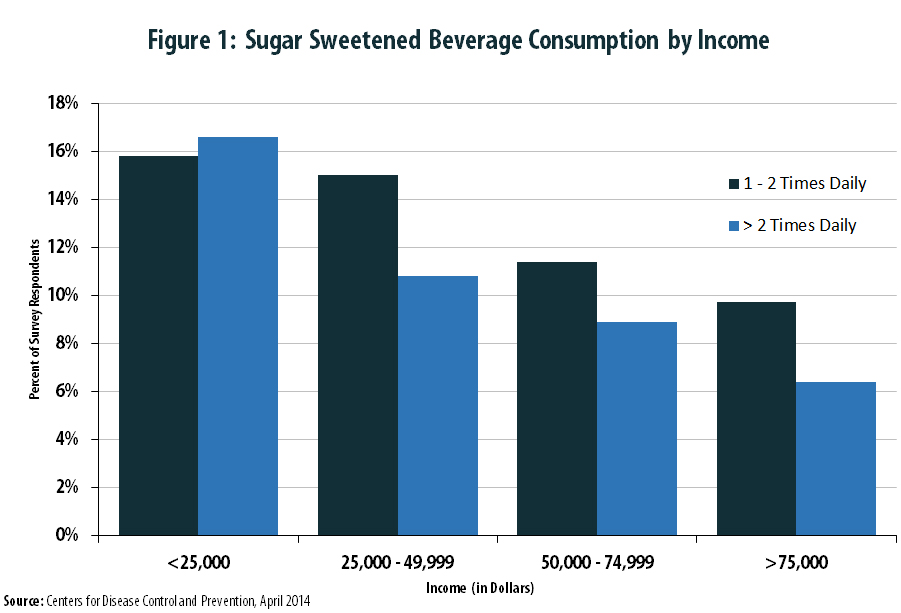

Soda taxes also impact individuals with lower incomes more because those individuals tend to consume more sugary drinks. Adults with lower incomes are more likely than those with higher incomes to consume significant quantities of sugar sweetened beverages (see Figure 1).[13] And rates of sugar sweetened beverage consumption are also higher among Black and Mexican adults than white adults.[14]

An Unsustainable Revenue Source

While excise taxes are better at targeting sugar consumption, their flat rate nature makes them an unsustainable source of revenue. Because the tax is levied at a constant rate the value of the tax will inevitably erode with inflation. A one-cent-per-ounce tax enacted a decade ago, for example, would be worth just 84 cents in today’s dollars.[15]

Moreover, the overt intention of a soda tax is to reduce consumption. If the tax has the desired effect, then jurisdictions should expect declining annual revenues. And soda consumption has already been declining nationwide for decades. In 2015 per capita soda consumption reached its lowest level since 1985.[16] US soda consumption peaked in the late 1990s at around 53 gallons per capita, but has steadily declined since—falling to 41 gallons per capita in 2014.[17], [18] This trend is likely to accelerate in jurisdictions that adopt soda taxes, thereby leading to an ever-shrinking revenue yield.

Jurisdictions that are considering a tax on sugar sweetened beverages as a revenue source for long-term budgetary needs should take a hard look at whether the revenue such taxes can raise will be available in the future.

Soda Taxes in the US

The prospect of implementing taxes on sugar sweetened beverages has been gaining traction across the country in recent years. While New York City’s attempt to implement such a tax in 2010 ultimately failed, the national attention it drew helped elevate the idea in the national dialogue.[19] Since then, Rep. Rosa DeLauro sponsored the SWEET Act in 2014 and 2015 to levy a federal one-cent excise tax per 4.2 grams of added sweetener.[20] And bills and ballot measures to tax sugary drinks have been considered in several states.[21]

The first tax on sugar sweetened beverages enacted in the US was approved by a ballot measure in Berkeley, California in 2014 and implemented in 2015. The tax levies a one cent per ounce excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages. The campaign was led by the Berkeley Healthy Child Coalition and focused on the detrimental health effects of sugar sweetened beverages. After a year of implementation, the city collected $1.2 million in revenue for the general fund, or less than one percent of city revenues in fiscal year 2015.[22] Initial research showed that in some low-income Berkeley communities, consumption of sugary beverages declined by 21 percent after the tax was levied.[23] Berkeley’s city council voted to use $1.5 million from the general fund to increase public health efforts aimed at further reducing consumption.[24] Further research will be needed to determine if this drop in consumption will persist, and if the change in behavior was the impact of the tax or other factors, such as attention drawn to sugary drinks by the campaign for the tax.

In 2016, the Philadelphia City Council approved a proposal from Mayor Jim Kenney to levy a 1.5-cents-per-ounce tax on sugar sweetened beverages and diet sodas. Notably, Philadelphia’s previous mayor, Michael Nutter, failed twice to advance a similar proposal.[25] While Mayor Nutter focused on the public health benefits, Kenney’s winning argument focused on the revenue gain that could be used for expanding pre-kindergarten and establishing community schools.[26] (Negotiations between the city council and the administration resulted in dedication of revenue to a broader array of services, but early childhood education will still receive the bulk of the funding.[27]) The tax will take effect on January 1, 2017. Philadelphia was the first large US city to approve a tax on sugar sweetened beverages.[28]

Ballot measures during the November 2016 elections led to taxes on sugar sweetened beverages in three Bay Area, California cities. Albany, Oakland, and San Francisco voters approved one-cent-per-ounce excise taxes on beverages with more than 25 calories per 12 ounces.[29]

San Francisco first asked voters to tax sugary drinks in 2014, but that measure failed. The 2014 San Francisco measure received a majority of votes in favor of the tax (55 percent), but the funds were earmarked for children’s physical education and nutrition programs. California law requires that ballot measures that earmark funds pass by a two-thirds majority. The 2014 Berkeley measure did not earmark funds, but rather the city council promised to use revenue from the new tax to support public health. Berkeley city officials kept their word, and Albany, Oakland, and San Francisco organizers followed Berkley’s lead when structuring their 2016 ballot measures.[30] Permitting the new revenue to go to the cities’ respective general funds helped secure the success of each measure — only Albany, the smallest district, secured more than two-thirds of the affirmative vote.[31]

The Albany tax took effect immediately upon passing of the measure.[32] Oakland will begin collecting the tax July 1, 2017.[33] And San Francisco’s measure will take effect January 1, 2018.[34]

2016 voters in Boulder, Colorado elected to levy a two-cent-per-ounce excise tax on drinks with more than 5 grams of added sugars per 12 ounces.[35] The measure passed after a contentious campaign that included a lawsuit filed by a beverage industry-backed resident.[36] The Boulder legislation commits the revenues to a range of public health uses and the administration of the tax. It will go into effect on July 1, 2017.[37]

Shortly after the November 2016 elections, the Cook County Board of Commissioners in Illinois approved a tax on sugar sweetened beverages. Cook County includes Chicago and surrounding suburbs and has a population of over 5.2 million residents, which is more populous than all other US localities with a sugar sweetened beverage tax combined.[38] Similarly to Philadelphia, the tax will be levied on beverages like diet sodas that are sweetened with zero-calorie sugar substitutes as well as sugar sweetened beverages.[39] But unlike any other US locality, the tax will be levied on consumers rather than distributors.[40]

2016 campaigns on soda taxes drew huge campaign contributions on both sides of the issue, mostly from national groups outside of the local jurisdictions. Former New York City mayor, Michael Bloomberg, led campaigns in support of the taxes. He spent a combined $4.7 million in support of the taxes in Cook County, Oakland, and San Francisco.[41], [42] The American Beverage Association opposed the measures, and spent $10.6 million in Cook County and the Bay Area.[43],[44] The concerted interests of public health and industry advocates and their willingness to spend on campaigns and legal action suggests that the debate on taxing sugary drinks in the US will not end soon.

Soda Taxes in Other Countries

Taxes on sugar sweetened beverages have also been implemented in other countries. With the World Health Organization’s recent recommendation to tax sugary drinks to combat obesity, it is possible that more countries will follow suit, particularly middle-income countries facing both climbing obesity rates and fiscal woes.[45]

One of the oldest taxes on soft drinks dates back to the 1930s in Denmark. The tax was repealed in 2014 amid concerns that it was dampening the economy and that Danes traveled to Sweden and Germany to buy sodas. The soft drinks were taxed at 1.64 Danish krone, or about 30 cents, per liter. [46]

France was one of the first countries to levy a tax on sodas in response to obesity. In 2012, France introduced a tax on artificially sweetened beverages, and in 2013 they added a separate tax for energy drinks. The country currently taxes sugary drinks at €0.753, or 83 cents, per liter. A proposal was introduced in June 2016 to increase the tax to €2.147 ($2.36) per liter.[47]

In 2013, the Mexican legislature approved a 1-peso-per-liter, or $0.053, tax on sodas. Initial studies have found that consumption in urban areas decreased by 5.1 percent in 2014, the first year the tax was levied.[48] But reports from manufacturers showed an increase in sales in 2015, and the revenues collected from the tax have exceeded government projections.[49]

The South African government proposed an unspecified tax on sugar sweetened beverages to combat obesity in the 2017 budget proposal.[50]

In their 2016 budget, the United Kingdom approved a tax that will go into effect in 2018. The tax has three tiers — a design which aims both to curtail consumption and to encourage producers to create products with less sugar. [51] Beverages with less than 5 grams of sugar per 100 milliliters will not be taxed. Those that contain between 5 and 8 grams per 100 milliliters would be taxed around 18 pence (22 cents) per liter. And beverages with more than 8 grams of sugar per 100 milliliters would be taxed around 24 pence (29 cents) per liter.[52] The tax is being delayed until 2018 to give manufacturers time to develop beverages with lower sugar content, and the exact amount of the tax has not been finalized.[53]

CONCLUSION

Both the advantages and disadvantages of a tax on sugar sweetened beverages are readily apparent. On the one hand, taxing these beverages may improve health outcomes, particularly for low-income people, and the taxes can generate meaningful revenues for public services. On the other hand, these taxes are regressive and are unlikely to generate a sustainable level of revenue in the long run. A careful weighing of these pros and cons is crucial to deciding whether levying a tax on sugar sweetened beverages is an appropriate policy choice.

[1] Sabrina Tavernise, “W.H.O. Urges Tax on Sugary Drinks to Fight Obesity.” The New York Times, October 11, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/12/health/sugar-drink-tax-world-health-organization.html?_r=1. R

[2] Connecticut General Assembly Office of Legal Research. “Taxes on Soft Drinks or Candy,” by Rute Pinho. 2012-R-0490 (Hartford, Connecticut, 2012) https://www.cga.ct.gov/2012/rpt/2012-R-0490.htm

[3] “The Sales Tax Clearinghouse,” 2016, https://thestc.com/strates.stm

[4] Connecticut General Assembly Office of Legal Research. “Taxes on Soft Drinks or Candy,” by Rute Pinho. 2012-R-0490 (Hartford, Connecticut, 2012) https://www.cga.ct.gov/2012/rpt/2012-R-0490.htm

[5] Sabrina Tavernise, “W.H.O. Urges Tax on Sugary Drinks to Fight Obesity.” The New York Times, October 11, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/12/health/sugar-drink-tax-world-health-organization.html?_r=1. R.

[6] Anna Gorman, “Soda Taxes: Gaining Steam or Getting Steamrolled?” Kaiser Health News, Jul. 15, 2016, http://khn.org/news/soda-taxes-gaining-steam-or-getting-steamrolled/.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Allison Aubrey, “Taxing Sugar: 5 Things To Know About Philly’s Soda Tax,” NPR, Jun. 9, 2016 http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/06/09/481390378/taxing-sugar-5-things-to-know-about-phillys-proposed-soda-tax.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Mandy Oaklander, “Should I Drink Diet Soda?” Time, Dec. 11, 2014, http://time.com/3628546/diet-soda-bad-for-you/

[11] Donald Marron, Maeve E. Gearing, John Iselin, “Should We Tax Unhealthy Foods and Sodas,” Tax Policy Center, Dec. 14, 2015, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/should-we-tax-unhealthy-foods-and-drinks/full

[12] Howard Gleckman, “Is a Salt Tax in Our Future?” Tax Policy Center, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/salt-tax-our-future

[13] Sohyun Park, Liping Pan, Bettylou Sherry, and Heidi M. Blanck, “Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Among Adults in 6 States: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011,” Preventing Chronic Disease, 2015, http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2014/pdf/13_0304.pdf.

[14] Cynthia L. Ogden, Brian K. Kit, Margaret D. Carroll, and Sohyun Park, “Consumption of Sugar Drinks in the United States, 2005-2008,” NCHS Data Brief No. 71, Aug. 2011, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db71.htm.

[15] Calculation based on the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index.

[16] Susana Kim, “US Soda Consumption at Its Lowest Level in 30 Years,” ABC News, Mar. 30, 2016, http://abcnews.go.com/Business/us-soda-consumption-lowest-level-30-years/story?id=38036424.

[17] Elena Holodny, “The epic collapse of American soda consumption in one chart,” Business Insider, Mar. 10, 2016, http://www.businessinsider.com/americans-are-drinking-less-soda-2016-3

[18] Margot Sanger-Katz, “The Decline of ‘Big Soda,’” The New York Times, Oct. 2, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/04/upshot/soda-industry-struggles-as-consumer-tastes-change.html?_r=0

[19] Anemona Hartocollis, “Failure of State Soda Tax Plan Reflects Power of an Antitax Message,” The New York Times (New York City, NY), Jul. 2, 2010 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/03/nyregion/03sodatax.html?_r=0

[20] H.R. 1687, 114th Cong. (2015). https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1687/text

[21] “SSB Campaign Map 2016,” Kick the Can, 2016, http://www.kickthecan.info/ssb-campaign-map-2016.

[22] “Budget Documents – City of Berkeley, CA,” City of Berkeley, Jun. 30, 2015 http://www.cityofberkeley.info/budgetdocuments/.

[23] Yasmin Anwar, “Soda tax linked to drop in sugary beverage drinking in Berkeley,” Berkeley News (Berkeley, CA), Aug 23, 2016 http://news.berkeley.edu/2016/08/23/sodadrinking/.

[24] Emilie Raguso, “Council approves $1.5M to fight soda consumption,” Berkeleyside, Jan. 20, 2016 http://www.berkeleyside.com/2016/01/20/berkeley-council-approves-1-5m-to-fight-soda-consumption/.

[25] Gabrielle Gurley, “Soda Taxes Hit a Sweet Spot,” The American Prospect, Jun. 24, 2016 http://prospect.org/article/soda-taxes-hit-sweet-spot.

[26] Jared Bre and Holly Otterbein, “The No-Bullshit Guide to the Fight Over the Philly Soda Tax,” Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA), Jun. 8, 2016 http://www.phillymag.com/citified/2016/06/08/soda-tax-no-bullshit-guide/.

[27] Claudia Vargas, Tricia L. Nadolny, and Julia Terruso, “Big chunk of soda tax money not going to pre-K,” Philly.com, Jun. 16, 2016 http://www.philly.com/philly/news/politics/20160614_Drink_tax_proposal_had_some_sweetners.html.

[28] Gabrielle Gurley, “Soda Taxes Hit a Sweet Spot,” The American Prospect, Jun. 24, 2016 http://prospect.org/article/soda-taxes-hit-sweet-spot.

[29] Har, Janie, “Things to Know About California Soda Tax Measures,” Bloomberg Government, Sept. 28, 2016 https://www.bgov.com/core/news/#!/articles/OE86YU3V7U9S? .

[30] Knight, Heather, “Berkeley kept its word on soda tax proceeds,” San Francisco Chronicle, Oct. 22, 2016, http://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/SF-soda-tax-changes-flavor-from-2014-10098368.php.

[31] Knight, Heather, “S.F., Oakland, Albany voters pass soda tax,” SF Gate, Nov. 8, 2016, http://www.sfgate.com/politics/article/Sugar-tax-measure-results-10593882.php.

[32] “Ballot Measures & Charter Amendments – November 2016,” City of Albany, 2016, http://www.albanyca.org/index.aspx?page=999.

[33] Ordinance #: 86161, City of Oakland, California (2016). http://www.acgov.org/rov/elections/20161108/documents/MeasureHH.pdf.

[34] “Sugary Drinks Distributor Tax Ordinance Legal Text,” City and County of San Francisco, 2016, http://sfgov.org/elections/sites/default/files/Documents/candidates/Sugary%20Legal%20Text.pdf.

[35] Burness, Alex, “Boulder business say they were duped by soda industry into joining anti-tax campaign,” Sept. 21, 2016, http://www.dailycamera.com/news/ci_30389604/boulder-businesses-say-they-were-duped-by-soda.

[36] Bear, John and Byars, Mitchell, “Judge clears way for soda tax to appear on Boulder ballot,” Daily Camera, Sept. 6, 2016, http://www.dailycamera.com/news/boulder/ci_30332570/judge-expected-rule-today-appeal-boulder-soda-tax.

[37] Ordinance No. 8130, City of Boulder, Colorado (2016). https://www-static.bouldercolorado.gov/docs/Ballot_Question_2H_Sugar-Sweetened_Beverages_Tax_-_Ordinance_No._8130-1-201609131010.pdf.

[38] Dardick, Hal, “Preckwinkle faces close vote by Cook County Board on beverage tax,” Chicago Tribune, Nov. 10, 2016 http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/politics/ct-cook-county-soda-pop-tax-vote-preview-met-1110-20161109-story.html.

[39] Dardick, Hal, “Preckwinkle faces close vote by Cook County Board on beverage tax,” Chicago Tribune, Nov. 10, 2016 http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/politics/ct-cook-county-soda-pop-tax-vote-preview-met-1110-20161109-story.html.

[40] Ordinance # 16-5931, Cook County Board of Commissioners, Illinois (2016). https://cook-county.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=2864031&GUID=8DDEE6A8-9125-4556-B93E-9D0D69774C08&Options=Advanced&Search=&FullText=1.

[41] Dardick, Hal, “Preckwinkle faces close vote by Cook County Board on beverage tax,” Chicago Tribune, Nov. 10, 2016 http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/politics/ct-cook-county-soda-pop-tax-vote-preview-met-1110-20161109-story.html.

[42] Har, Janie, “US soda-tax battle bubbles up in San Francisco Bay Area,” Associated Press, Sept. 28, 2016, https://apnews.com/fe3ba56e369e4022839f1003dfa744d7/soda-tax-battle-bubbles-san-francisco-bay-area.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Dardick, Hal, “Preckwinkle faces close vote by Cook County Board on beverage tax,” Chicago Tribune, Nov. 10, 2016 http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/politics/ct-cook-county-soda-pop-tax-vote-preview-met-1110-20161109-story.html.

[45] Sabrina Tavernise, “W.H.O. Urges Tax on Sugary Drinks to Fight Obesity.” The New York Times, Oct. 11, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/12/health/sugar-drink-tax-world-health-organization.html?_r=1. R.

[46] Caroline Scott-Thomas, “Denmark to scrap decades-old soft drink tax,” Foodnavigator.com, Apr. 25, 2013, http://www.foodnavigator.com/Policy/Denmark-to-scrap-decades-old-soft-drink-tax.

[47] “France could hike taxes on soda and chocolate bars,” Jun. 22, 2016, https://www.thelocal.fr/20160622/the-price-of-sugary-drinks-in-france-may-be-on-the-rise

[48] Carolina Batis, Juan A. Rivera, Barry M. Popkin, and Lindsey Smith Taillie, “First-Year Evaluation of Mexico’s Tax on Nonessential Energy-Dense Foods: An Observational Study,” Public Library of Science, (2016) http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1002057

[49] Amy Guthrie and Mike Esterl, “Soda Sales in Mexico Rise Despite Tax.” The Wall Street Journal, May 3, 2016, http://www.wsj.com/articles/soda-sales-in-mexico-rise-despite-tax-1462267808.

[50] “2016 People’s Guide,” The National Treasury, 2016, http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2016/guides/2016%20People’s%20Guide%20English.pdf.

[51] Donald Marron, “Britain Builds a Better Soda Tax,” dmarron.com, Mar. 22, 2016, https://dmarron.com/2016/03/22/britain-builds-a-better-soda-tax/.

[52] Nick Triggle, “Sugar tax: How will it work?” BBC, Mar. 16, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/health-35824071.

[53] Donald Marron, “Britain Builds a Better Soda Tax,” dmarron.com, Mar. 22, 2016, https://dmarron.com/2016/03/22/britain-builds-a-better-soda-tax/.