Key Findings

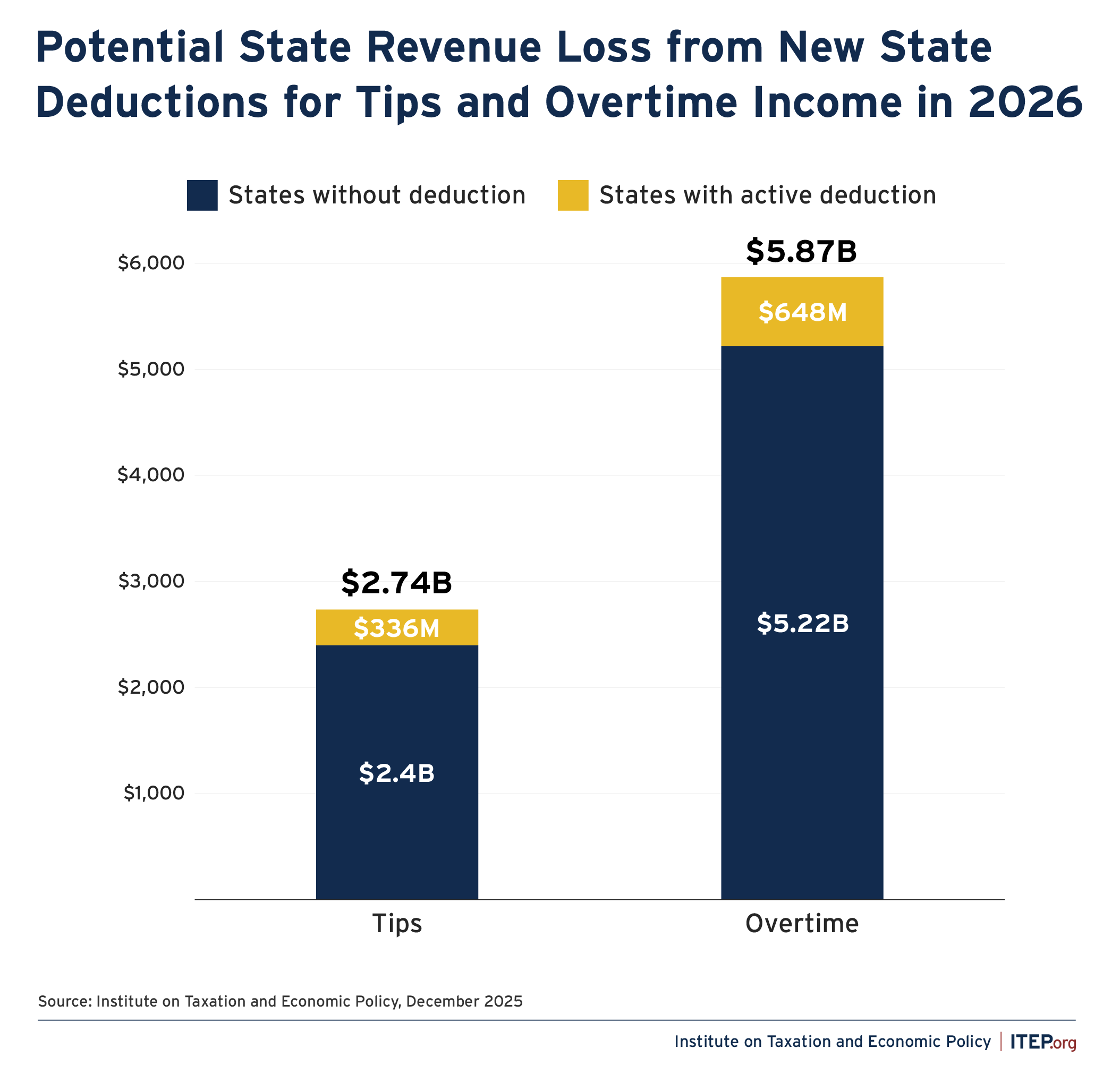

- Congress recently enacted new tax breaks for tips and overtime income that are expected to lower federal revenues by $33 billion a year. States must now decide whether they want to mirror these deductions in their own income tax laws. If all states decided to go along with these deductions, the cost to states would be $8.6 billion in 2026.

- Eight states have tax codes currently linked to the tipped income deduction. These states (Colorado, Idaho, Iowa, Michigan, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, and South Carolina) stand to lose $336 million in tax revenue in 2026 as a result.

- Seven states are currently connected to the overtime deduction. These states (Idaho, Iowa, Michigan, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, and South Carolina) stand to lose $648 million in revenue in 2026.

- Depending on the response to these policies by employers, who might seek to capitalize on these new carveouts by adopting tip-centric compensation structures or steering workers into tax-preferred overtime hours, the revenue loss associated with these policies could be even larger than forecast here.

- Because deductions for tips and overtime income offer no benefit to most people, they unproductively divide workers with some getting preferential tax treatment that is denied to others. Lawmakers should forgo these carveouts in favor of more principled policies that benefit a broader swath of workers.

Introduction

As states consider the effects of the 2025 Trump tax law (the so-called “One Big Beautiful Bill Act”) and how these federal changes will impact state revenues, lawmakers should push back on any attempt to link or remain linked to the federal bill’s deductions for tipped and overtime income.

These limited deductions were enacted primarily to distract from the windfall given to our nation’s wealthiest residents in the new law. They do very little to help working Americans make ends meet while deepening the federal deficit to the tune of $33 billion each year.

While just a handful of states will automatically adopt these deductions,1 some state lawmakers are considering linking to this section of the Internal Revenue Code. These deductions are an ineffective way to support low- and moderate-income workers and will place more strain on state revenues that fund services that those workers need and want. States that are currently linked to the section of the Internal Revenue Code housing these provisions, IRC Section 63(b), should decouple as soon as possible while lawmakers in other states should oppose any effort to actively connect to these provisions.

New Federal Deductions for Tips and Overtime

The 2025 tax law will temporarily allow some workers to deduct income from tips or overtime on their federal tax forms, up to a certain amount. These deductions are scheduled to remain in place for the 2025 through 2028 tax years, though federal lawmakers will undoubtedly consider extending them beyond that date.

Under the new law, workers hoping to take advantage of the deduction for tips are supposed to be employed in occupations which “customarily and regularly received tips on or before December 31, 2024.” The details of that definition were left to the Treasury Department, which is moving forward with an expansive list of 68 occupations, including rarely tipped ones such as plumbers, electricians, and air conditioning installers. Tipped workers who file their taxes with a Social Security number can receive a maximum deduction of $25,000 a year, with the deduction amount phasing out for people with more than $150,000 of annual income for single filers or $300,000 of income for married filers.

The overtime deduction is not limited to certain professions, but it maintains a cap on income and amount. Workers who receive “time-and-a-half” pay while working overtime can deduct their overtime pay (the “half”) up to $12,500 a year for single filers and $25,000 a year for married filers. Like the tipped income deduction, these amounts will begin to phase out after $150,000 of annual income ($300,000 for married filers) and must be claimed by filing taxes with a Social Security number.

Costs to State Revenue

Allowing taxpayers to deduct tips and overtime on their state tax forms would cost states significant revenue at a time when state budgets are increasingly stretched thin – a fiscal situation likely to worsen in the coming years as federal funding cuts come online. States currently connected to the tipped income deduction – including Colorado, Idaho, Iowa, Michigan, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, and South Carolina – can expect to lose $336 million collectively in 2026. States currently linked to the overtime deduction – Idaho, Iowa, Michigan, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, and South Carolina – can expect to lose $648 million in 2026.

As of this writing, Michigan is the only state where lawmakers actively chose to connect to the tipped and overtime income deductions. The other states are coupled by default due to the specific design of their tax codes. The decision to link to the tipped income deduction will cost Michigan $105 million in 2026, while the overtime deduction will cost the state $207 million in 2026.

If every state linked to these provisions, it would result in $8.6 billion of lost revenue for states in 2026.

Figure 1

While a revenue loss of this magnitude is concerning, there is also a risk that the true impact of these policies could be even larger. Analyzing the effect of entirely new tax carveouts for which little data has been collected on past tax forms is inherently challenging. In Alabama, for example, lawmakers in 2023 enacted a temporary exemption for overtime income but later chose to let that exemption expire when it became apparent that the resulting revenue loss was much larger than anticipated.

Recent actions at the Treasury Department raise concerns that the new federal deductions – and any state deductions based on them – could also cost more than expected. In the months following enactment, the Department has adopted a very permissive stance toward implementation of the tips deduction, in particular, that will grow the cost of that policy relative to what would be suggested by a plain reading of the statute. In addition to extending the deduction to several occupations which have not “customarily and regularly received tips,” as mentioned above, Treasury has also temporarily discarded industry-specific limitations that were meant to bar individuals working in fields like consulting, health, athletics, and the performing arts from receiving the deduction.

While some state lawmakers have filed bills to connect their state tax codes to these tips and overtime deductions, other states have outright rejected these measures. Maine Gov. Janet Mills, for example, issued instructions to the state’s tax assessor that Maine not conform to the tips and overtime deductions. Similarly, the District of Columbia’s city council passed legislation reinforcing the District’s decoupling from both deductions. Colorado – which was linked to both deductions by default – chose to actively decouple from the overtime deduction, saving the state $119 million in 2026.

An Ineffective Way to Support Workers

Deductions for tips and overtime income are a smoke-and-mirrors approach that does not provide genuine, broad-based support for hourly-waged workers who keep our economy running. While the policies are being marketed as support for low-income and middle-class workers, most of those workers will be left behind by these deductions and there are considerable opportunities for companies rather than workers to capture some of the benefits.

First and foremost, very few workers qualify for these deductions. Of workers earning less than $25 an hour, just 5.2 percent are in occupations that tend to rely on tips. Among workers overall, just 6 percent2 report receiving overtime income. And even some of those workers who receive tips or overtime pay would be partly or fully excluded from receiving these state-level deductions if they earn too little to owe state personal income tax.

Exempting tips and overtime income unproductively divides the working class into those considered worthy and unworthy of preferential tax treatment. In tax parlance, this is known as violating the “horizontal equity” principle of fair taxation—the idea that two workers with similar incomes in similar households should pay similar amounts in tax. But you don’t need to be a tax wonk to see that carving out exemptions that favor certain professions over others is nonsensical – why should a waiter or bartender making $30,000 a year, largely through tips, pay significantly less income tax than a child care worker or a line cook at a fast-food restaurant who is paid the same amount? Instead of creating winners and losers in our tax system, state lawmakers should be pushing to foster economic security among the working class more broadly. For the same cost of creating tips and overtime carveouts for workers in certain favored professions, Congress could have expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit by almost 50 percent3 – a move that would have improved the fortunes of lower-paid workers regardless of their profession.

There is also good reason to think these policies could provide a windfall to employers that undercuts the financial benefit that workers might otherwise receive.

Exempting tips from state income tax could put downward pressure on hourly wages as employers pivot to relying on tips to compensate workers for providing services. That is, instead of providing wage increases for hotel desk clerks, housekeepers, lawn care workers, or one of the other 68 occupations identified by the Treasury Department as deserving access to the deduction, their employers could instead push to expand tipping culture to compensate for underpaying these employees. Faced with the choice of either updating hourly wages to reflect inflation, for instance, or inching up the “suggested tip” percentages that appear at checkout, the tips deduction makes it more likely that employers will opt for the latter.

Deductions for overtime income could also put downward pressure on wages. The 40-hour work week was a hard-fought labor policy, and time-and-a-half pay for overtime forces employers to hire adequate staff as opposed to exploiting a smaller group of workers through unreasonably long work weeks. Exempting overtime pay from state taxes would incentivize reclassifying positions as hourly, with one upshot being that employers could harness the new overtime deduction as a tool for coaxing longer hours out of their workers. Even worse, some employers may be tempted to curb future pay raises in favor of holding untaxed overtime hours over the heads of employees who now need the extra shifts to make ends meet.

Conclusion

Working people in the United States struggle to make ends meet. It is imperative that we meet that need with real solutions that improve incomes and lives. Special tax carveouts for narrow types of income are not the right approach.

State deductions for tips and overtime will come at a substantial cost to state budgets, potentially stretching into billions of dollars per year, while lowering taxes for only a small sliver of people concentrated in certain professions and offering no benefit to most working-class people.

Rather than dividing the working class and giving new income tax carveouts to some while excluding others, the public would be better served by consistent tax reforms that benefit the working class more broadly.

Methodology

To estimate the amount of tips potentially deducted under state income tax law as a result of conformity to the new federal policy, we start with IRS data on the aggregate amount of reported tips and distribute that amount by state and income level using data obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS-ASEC) alongside state level data on wages in tipped occupations from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) program. When distributing the total reported tips across states and income groups, we use a subset of all frequently-tipped occupations to represent the larger group of tipped workers. These include waiters and waitresses; bartenders; gambling services workers; barbers; hairdressers, hairstylists, and cosmetologists; manicurists and pedicurists; skincare specialists; other personal appearance workers; and dining room and cafeteria attendants and bartender helpers. Our estimates are then calibrated such that the federal revenue effect resulting from this deduction aligns with the official estimate from the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), thereby allowing us to capture the impact on the full set of affected workers.

For overtime pay, we use data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to estimate the total volume of overtime hours and wages by occupation and distribute those amounts to states based on the occupational composition of their workforces. Data from the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) is then used to further distribute that pay across income groups. As with our estimates for tips, our overtime estimates are also calibrated to match the official JCT revenue estimate.

The resulting tip and overtime estimates are aged to 2026 levels using projected wage and salary growth and are fed into our microsimulation tax model to calculate the overall cost of these deductions to each state based on how they interact with its unique income tax structure. Additional revenue losses from these deductions for localities that levy local income taxes are not included in these estimates.

Because our methodology is calibrated to produce a federal revenue impact that aligns with the official JCT score, it implicitly assumes the same level of behavioral response predicted by JCT in its official estimate. While JCT has not disclosed the size of that response in this particular case, it does routinely take such responses into account as part of its revenue estimating process.

Given the novelty of these deductions, however, the magnitude of the behavioral response is subject to considerable uncertainty. Changes to work schedules or compensation structures that increase the share of income taking the form of overtime or tips will increase the cost of these deductions. While it is a well-known fact among tax policy analysts and practitioners that singling out certain forms of income for preferential treatment incentivizes taxpayers to search for ways to reclassify their income into the tax-preferred category, the degree to which this will occur is difficult to predict and may vary across states, industries, and time periods.

Proposed regulations from the Treasury Department have also created reason for concern that the cost of the tips deduction, in particular, could be higher than anticipated by JCT. While the statute specifies that only workers employed in occupations which “customarily and regularly received tips on or before December 31, 2024” should qualify for the tips deduction, Treasury has interpreted that to include some rarely-tipped professions such as electricians and air conditioning installers that were not necessarily on the minds of JCT analysts when they were thinking through possible behavioral responses to the new law. Moreover, Treasury has decided to temporarily ignore a provision of the new law prohibiting workers in certain industries from claiming the tips deduction—specifically, workers employed at a “Specified Service Trade or Business (SSTB)” in fields like consulting, health, athletics, and the performing arts. Expanding the deduction to workers in these industries will increase the cost of the tips deduction beyond what Congress enacted.

Endnotes

- 1. States that start their state income tax calculations using Federal Taxable Income as opposed to Federal Adjusted Gross Income will automatically be coupled to these deductions.

- 2. ITEP analysis of data from the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

- 3. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that new deductions for tips and overtime income will reduce federal revenues by $33.3 billion in FY27. This equals 48 percent of the $69.5 billion that JCT expects the Earned Income Tax Credit to cost in that year.