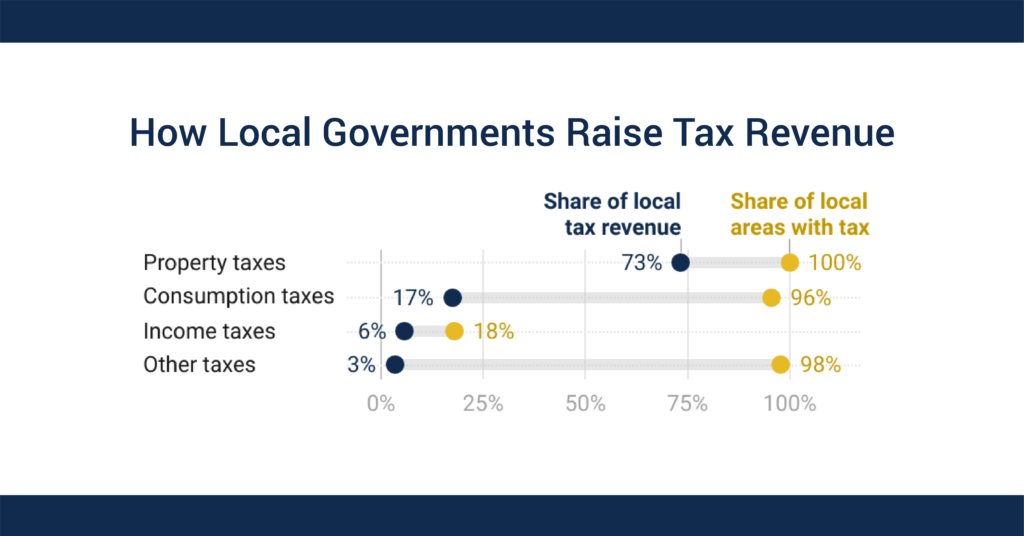

Property taxes are the backbone of local governments, generating approximately three in four local tax dollars nationwide. They are essential for funding schools, transit, parks, libraries, health departments, and other public services. Property taxes have historically been regarded as a relatively stable and broad-based funding source, but flawed tax administration practices, state constraints, and certain policy decisions contribute to their regressivity. This inequity gives rise to distinct racial disparities.

It doesn’t have to be this way: proven policy solutions like property tax circuit breakers can promote property tax affordability and advance equity.

In his new book, The Black Tax: 150 Years of Theft, Exploitation, and Dispossession in America, Professor Andrew Kahrl walks readers through the history of the property tax system and its structural defects that have led to widespread discrimination against Black Americans. His book reveals the consequences of inequitable and predatory property tax laws and how Black residents fought back within this unjust and unbalanced system. The book offers a hugely valuable historical account that puts present day efforts to reform this vital revenue source into the proper context.

Professor Kahrl was kind enough to field a few of my questions about his work. You can see our conversation below, which has been edited for length and clarity.

In your book, you talk about property tax systems as being a major culprit behind the economic exclusion of Black Americans over the past 150 years. Can you give us an example of what that looks like in practice?

Because property taxes are levied at the state and local level, they have played a key role in fueling segregation and exclusion in housing markets and public schools since the 20th century.

After World War II American middle-class white families flocked to the suburbs and formed new municipalities and school districts. This allowed them to keep their local property tax dollars and not share them with the areas they left behind.

The fragmentation of metropolitan America into separate and unequal tax bases created winners and losers: suburban towns and school districts with sizable tax bases relative to population size, which allowed them to tax property at a lower rate to fund quality services and schools; and central cities with shrinking tax bases and mounting needs, forcing them to tax property at higher rates while generating less revenue.

Moreover, majority-Black cities and school districts were forced to tax residential property heavily to generate barely enough revenue to maintain basic services. By the late 1960s, for example, cities like Gary, Indiana, and Newark, New Jersey, had some of the highest property tax rates at the same time their school systems and public services suffered from chronic underfunding.

This dynamic gave white middle- and upper-class beneficiaries strong incentives to pursue exclusionary policies that limited the presence of the poor and people of color, who were seen as “consuming” more local tax dollars while driving down property values and, with it, shrinking local tax bases.

You write about both political and legal campaigns to change property tax policy. Has one strategy tended to yield more results than the other? Do you view these two approaches as an either/or proposition, or do you see them as complementing each other?

At a national level, there have been sporadic attempts to address problems with local property tax administration that result in the gross under-taxation of certain properties and over-taxation of others. Most notably in the early 1970s, Congress held hearings in response to a spate of scandals involving local assessors’ offices and President Richard Nixon made property tax reform a part of his 1972 re-election campaign. But that moment passed without any federal legislation.

During these same years, there were legal campaigns aimed at diminishing the role of local property taxes in public school funding, culminating in the Serrano decision by the California Supreme Court, which found that the state’s reliance on local property taxes to fund public education — and the disparities in funding between wealthy and poorer school districts that resulted — violated the equal protection clause of the US and state’s Constitution. In the 1973 Supreme Court case, Rodriquez v. San Antonio Independent School District, a 5-4 conservative majority upheld Texas’ funding formula, ruling that the funding inequalities and, for some districts, the inability to raise the revenue from property taxes needed to provide children with an adequate education, was constitutional. In the decades since, the fight for a more equitable system for funding public education moved down to the state courts, with decidedly mixed results.

Since the early 1970s, political campaigns for property tax reform have taken place almost exclusively at the state and local level. And these campaigns have achieved considerable success, but the results have been to make property taxes less fair and funding for public goods and services more unequal. I’m speaking of the tax revolts that began in California with the passage of Prop 13 in 1978 and quickly spread to other states. Proponents wanted across-the-board property tax cuts, not corrections to fix the inequitable assessment of properties that forced low-income communities to pay higher effective rates than wealthier ones. The assessment reductions and limits on future increases that resulted from these reforms also made the property tax more regressive.

I think one lesson from this era in the 1970s and early 80s is that the movement for progressive reforms to local tax systems cannot rely on either the courts or political leaders to instigate change. It needs to emerge from grassroots activism and speak to the everyday struggles and frustrations of those most disadvantaged by the current system. It also, crucially, needs to offer a concrete vision of a better alternative.

The administration of the property tax has evolved over time. Do you have any overarching takeaways in how it’s changed? What are some key differences and similarities across historical eras in how discriminatory practices have shown up in the property tax system?

During the antebellum era, two distinct approaches to tax administration emerged in the North and South. Whereas northern states developed more advanced systems for assessing property and raising revenue, southern states placed statutory constraints on taxation of the region’s most valuable property (enslaved persons) and, by design, relied on crude accounting methods that allowed for rampant tax avoidance and fictitious valuation, and generated small tax returns.

This led to concentrated wealth and power and limited the formation of public institutions and provision of public services across the South. In practice, tax administration in the South adhered to the principle that the ruling class need only pay as they pleased, that the assessed value of their property and their tax obligations were what they, and only they, wished them to be. Of course, the reverse was also true: that the tax obligations of subordinate classes, the value of the properties they held, were also what the ruling class deemed them to be.

Following the overthrow of Reconstruction, white “redeemers” resumed the practice of favorably undervaluing for tax purposes the property of wealthy, large landowners and, conversely, overvaluing the small landholdings and homes of Black people.

Alabama was the first state to place strict limits on the amount of revenue that could be raised from property taxes, which left public institutions, especially public-school systems, starved of revenue and, in practice, forced Blacks to shoulder a comparatively heavy tax burden. Black disfranchisement and the full-scale withdrawal of the federal government from local governing affairs in the South allowed white tax assessors to engage in discriminatory taxation with virtual impunity, and throughout this era, property assessments were less a measure of a property’s actual value and more a reflection of the status and power of the person who owned it, with those holding the most power taxed the least and those lacking in power (especially, Black people) taxed the most—all the while getting little to nothing in return.

Local tax administrators, I also found, could also be instrumental in facilitating the theft of Black land and homes and in silencing Black defiance of Jim Crow. There are many examples I describe in my book of Black owners of valuable land not receiving a tax bill, or not having their tax payment recorded, and subsequently having it sold for unpaid taxes at a local tax sale. There were other instances when African American individuals or entire communities challenged Jim Crow through protests, boycotts, and marches, only to see their property assessments sharply increase.

What was perhaps most frustrating to victims of over-taxation at the time is that the civil rights revolution and the landmark cases and federal legislation enacted during this era did nothing to curb these abuses. Then, and now, victims of discriminatory taxation at the hands of local officials cannot seek relief in the federal courts. Instead, Black southerners had to fight for greater fairness and transparency in local tax administration through the political process, by electing tax assessors who rooted out favoritism in property valuations and by pressing state lawmakers to enact reforms that established standards and requirements for tax administration where none previously existed.

In northern states, it was a different story. Northern states were on the leading edge of progressive tax reform and modernization in the early 20th century.

Wisconsin adopted the first state income tax in 1911 and its method for taxing income became a model that other states and, later, the federal government would emulate. As these states adopted new statewide taxes, they made the property tax strictly a local tax – administered, collected, and spent at the county and municipal level. As it did, state legislatures became less concerned about how this tax was administered locally and afforded local tax assessors a great degree of autonomy and discretion.

Among these was the practice of assessing properties at a fraction of their full value, an often informal but pervasive practice. Strictly speaking, whether a property is assessed at its full value or a fraction thereof makes no difference in the tax bill one pays. But what fractional assessments did, in practice, was disguise inaccuracies and favoritism, and made it difficult for the average taxpayer to know whether they were being taxed fairly. So, one significant reform that took place was the formalization of fractional assessments and the creation of different statutory fractions for different types of property: residential, commercial, industrial, agricultural, etc.

Another change was local governments’ adoption of computerized systems for assessing property and contracting with professional firms to conduct mass reassessments, which unfolded during the 1960s and 1970s. But, as my book shows, these more advanced and seemingly objective systems for valuing property did not root out discriminatory practices and unequal results.

One of the things I found when looking closely at tax administration in northern cities was that these persistent patterns of unequal taxation were less the result of racist assessors intentionally seeking to overtax communities of color – though there were some instances of that – and more the end result of numerous tax breaks and generously low assessments awarded to the people and businesses that cities were keen on attracting and retaining.

Then and now, one of the chief causes of unequal tax assessments is simply inaction: failing to update assessments to reflect changes in the market. This is something that varies from state to state. Some states require assessments to be updated annually, others every two, three, or more years, and others still have no requirement for updating assessments at all. The longer the time between updates, the more owners of property that has appreciated more rapidly in value in the interim stand to benefit. Which means that homeowners and real estate developers in areas where values are rising more rapidly greatly benefit from assessor inaction, while people living in areas where values remain stagnant or falling stand to lose.

As a whole, one thing that stands out in the history of local tax administration is just how little has changed over the 150 years my book covers. Certainly, tax administration has become more professional and, to a greater or lesser degree, more transparent. And that’s the case in both southern and northern states. But the rules governing local tax administration and the methods and procedures used by local officials still vary wildly from state to state and even from county to county within states.

The property tax is a tremendously important source of revenue for local and state governments and it’s vital that we administer these taxes as fairly as possible. How would you suggest someone get involved with making their property tax system less discriminatory?

As for fixing the immediate problems with property tax administration and enforcement, readers can learn lessons from movements and organizations in the past that I highlight in my book, like the anti-poverty organizer and activist George Wiley and the Movement for Economic Justice, and the organizing and educational efforts of Chicago’s Black Taxpayers Federation. Both prioritized coalition building and bringing tax policy down to a level that average citizens could understand. The less abstract we make these problems, the more we can see ourselves and our futures bound up in them, and the more they become something worth fighting to end.

I would also say that we should look at the system as a whole and the inequalities it perpetuates. They are the predictable results of the fiscal structure we built.

Take predatory tax lien investing and its devastating effects on low-income and minority communities today, not to mention its role in draining untold billions of dollars in land, homes, and earnings out of Black communities over the past 150 years. There were outrageous miscarriages of justice and outright theft happening at local tax auctions and through the machinations of tax buyers, as I describe in often-horrific detail throughout my book.

And even more disturbing were the routine, and absolutely legal, forms of exploitation and dispossession that were—and remain—intrinsic to how we enforce property tax compliance and handle tax delinquency. Ensuring that these laws are applied fairly and without favor won’t solve these problems, for the laws themselves are the problem.

Ultimately, I hope the history this book tells will offer some valuable lessons for those fighting for more robust funding for the public institutions, goods, and services that property taxes support and a more equitable distribution of the public’s money—at the local, state, and federal level.

I also hope it will help further the fight to transform America’s system for generating the public’s money, from our current one that taxes the meager earnings and assets of the poor and works, in practice, to compound existing inequalities, to one that taxes—heavily—the vast and immensely concentrated wealth of those at the top, and uses it to address the problems that extreme inequality has generated, and, ultimately, moves us toward a more equal future. That is the fight that must be waged. African-Americans’ experiences as taxpayers in the past helps us better understand how we got here, and the challenges that lie ahead.

Further reading from ITEP:

- America Used to Have a Wealth Tax: The Forgotten History of the General Property Tax (November 2023)

- States are Talking About the Wrong Kind of Property Tax Cuts (May 2023)

- Preventing an Overload: How Property Tax Circuit Breakers Promote Housing Affordability (May 2023)

- Creating Racially and Economically Equitable Tax Policy in the South (June 2022)

- Racial Discrimination in Home Appraisals Is a Problem That’s Now Getting Federal Attention (March 2022)

- Gentrification and the Property Tax: How Circuit Breakers Can Help (April 2021)

- Capping Property Taxes: A Primer (September 2011)

- How Property Taxes Work (August 2011)