Taxes are calculated by multiplying a tax rate by a tax base (the things being taxed). Broader tax bases allow for lower tax rates while raising the same amount of revenue.

It’s often helpful to differentiate nominal rates (the rate written into law) from effective tax rates (what people actually pay relative to their income).

The Tax Base

The tax base is made up of all the items or activities upon which tax is owed.

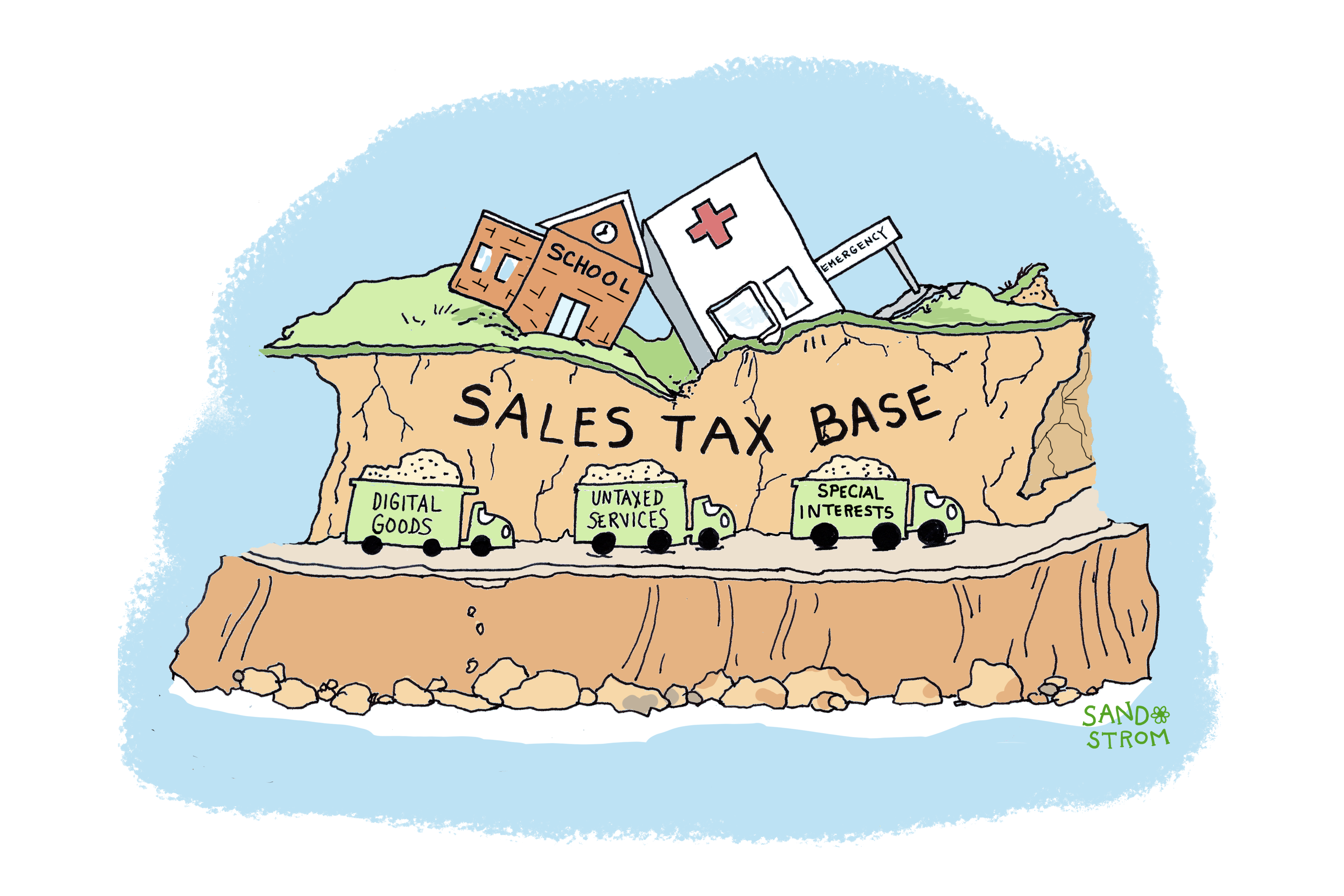

For any tax, there is usually a difference between the potential tax base—the set of items that would be taxed if there were no special exemptions—and the actual tax base The potential tax base of a state’s general sales tax, for instance, is everything that consumers purchase in that state. But in every state levying a sales tax, the actual tax base is much smaller than that, because of exemptions for everything from groceries to software that allow some sales to go untaxed.

Tax bases are usually measured as a dollar amount to which a tax rate is applied—for example, the total dollar amount of taxable income, in the case of the personal income tax, or the total dollar value of real estate, in the case of the real property tax. Taxes that are measured this way are called ad valorem, or value-based, taxes.

But not all taxes are calculated based on value: excise taxes on cigarettes, gasoline, and beer are usually calculated on a per-unit basis. The amount collected by these taxes depends on the number of units sold. Gasoline taxes, for instance, are applied on a per-gallon basis and expressed as a certain number of cents per gallon sold. Thus, for a gas tax, the tax base is usually the number of gallons sold, and it fluctuates based on variation in the demand for gasoline rather than the price.

In other words, tax revenues for unit-based taxes like excise taxes only increase when the number of units sold go up, a critical flaw as they do not naturally adjust to match price changes. By contrast, ad valorem taxes tend to grow with inflation even when the number of units sold is unchanged, because inflation drives the value of the base upwards.

Broad Bases Are Best

Taxes can be described as having a broad base or a narrow base. A broad-based tax is one that taxes most of the potential tax base. A narrowly based tax applies to fewer items. For example, a broad-based sales tax is one that applies to almost all purchases of goods and services. A narrower sales tax applies only to goods, not services, and has exemptions for things like food, housing, medicine, and more.

In general, broader tax bases are a good idea. Broad based taxes can raise more revenue than narrow-based taxes—simply because more is taxed. Because more is taxable, the broader the base, the lower tax rates can be. And the narrower the tax base, the higher the tax rate must be to fund a given level of public services.

A broader base also makes it more likely that the tax system will treat all economic activities the same, which helps ensure that the tax system will not discriminate in favor of some taxpayers and against others.

For example, income tax rules that favor investors’ income over that of wage earners shift more of the responsibility of funding public services onto modest-income working families. In the case of sales taxes, broad tax bases include all goods, services, and internet sales, which prevents creating unfair advantages for some sectors and not others. Broad bases also offer greater revenue stability and long-term growth, because they capture activity across the whole economy rather than just certain sectors.

But sometimes there are good reasons for having a narrower base. For example, most income taxes exclude very low incomes, generally with exemptions and deductions that shield incomes, up to a certain amount, from taxation. That’s because taxing very low-income households worsens poverty and comes at a greater cost to society than the taxes that would be raised. Narrowing the income tax base in this way helps to make it more progressive, asking more from families with greater ability to pay.

The Tax Rate (or Rates)

Multiplying the tax rate times the tax base gives the amount of tax owed. Usually, the tax rate is a percentage. For instance, if a state’s sales tax rate is 4 percent on each taxable purchase and taxable purchases (the tax base) total $1 billion, then the total amount of tax collected will be $40 million (4 percent of $1 billion).

Income taxes often use graduated rates.

Not all tax rates are percentages. A typical gasoline tax rate, for example, is expressed in per-gallon terms. So if a state has a gasoline tax rate of 10 cents per gallon and 100 million gallons of gasoline are sold, then the tax collected will be $10 million (10 cents multiplied by 100 million).

Property tax rates are traditionally measured not in percentages but in mills. Mills tell us the tax for each thousand dollars in property value. Thus, a 20 mill rate applied to a house with a taxable value of $200,000 yields a tax bill of $4,000 for the owner.

Nominal Versus Effective Rates

So far, we have been describing nominal tax rates—the actual legal rate that is multiplied by the tax base to yield the amount of tax liability. Though the nominal rate is used in the actual calculation of taxes, it’s not the best measure for comparing taxes between states because it doesn’t account for differences between tax bases.

For example, two states with identical sales tax rates, populations, total sales, and total income will have different effective tax rates if they define their tax bases differently. State A’s sales tax applies to a narrow tax base, exempting groceries and many services, while state B’s sales tax applies to a broader tax base. As a result, State A’s tax base is smaller, applying to only $1 billion in sales, while State B’s tax applies to $1.5 billion in sales. State B’s sales tax is obviously much higher than State A’s tax—even though the legal rates are identical. To compare these two sales taxes solely based on the legal rates would be misleading.

A better, more accurate measure for comparing these taxes is the effective tax rate. The idea of an effective rate is that instead of just saying “both state A and state B have 4 percent sales taxes,” we say that “state A’s sales tax takes 2 percent of the income of its residents while state B’s takes 3 percent of personal income.” This approach is better because it measures tax liability in a way that takes account of differences in the tax base.

In this example, by comparing these effective rates we see that, even though state A and state B have the same nominal rates, the tax is higher in state B because state B has a broader base. When we divide tax payments by personal income, as in the example above, we’re calculating the effective tax rate on income—the best measure we have of ability to pay.

Effective tax rates can be calculated in other ways, too. For example, the property tax on a home can be expressed as a percentage of its market value. But what if we want to measure the tax compared to what the homeowner can afford? The owner of this home could be out of work—or could have just gotten a huge raise. Because we care about tax fairness, we need to measure the tax paid relative to ability to pay. Tax incidence tables—like the ones presented in ITEP’s “Who Pays” report and other ITEP analyses of tax fairness—are based on effective tax rates on income for families at different income levels because this approach is the most meaningful measure of tax fairness.

Related Entries

What Principles Should Guide State and Local Tax Policy?

State and local taxes exist primarily to fund schools, roads, health care, and other services needed for communities to thrive. There are multiple ways to achieve this goal, so it can be helpful to evaluate different options based on a few core principles.

What’s Exempt from State and Local Sales Taxes?

State and local sales taxes are typically conceived as broad-based consumption taxes – that is, taxes on most things consumers buy. In practice, many purchases are exempt from sales taxes.

How Do State and Local Personal Income Taxes Work?

The personal income tax funds public education, health care, public safety, and other public services provided by state and local governments. If well-designed, it is the fairest major revenue source available to states.

How Do Real Property Taxes Work?

Property taxes on land and buildings are the oldest and still the largest major revenue source for state and local governments. They fund schools, health care, public safety, and other services. They are collected mostly by cities, counties, school districts, and other types of local government, but states typically make the rules for assessing the value of property and imposing the tax, with major implications for tax fairness and adequacy.

Learn More

- Byerly-Duke, Eli, and Carl Davis (2024). “Is California Really a High-Tax State?” ITEP.

- Davis, Carl (2025). “Two in Three Americans Live in States with Variable-Rate Gas Taxes.” ITEP.