U.S. territories collect taxes to fund schools, roads, health care, and other services, somewhat like states do. They levy income taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, and other typical state and local taxes.

These taxes can have important progressive elements, but territorial status poses unique challenges for fair and adequate taxation.

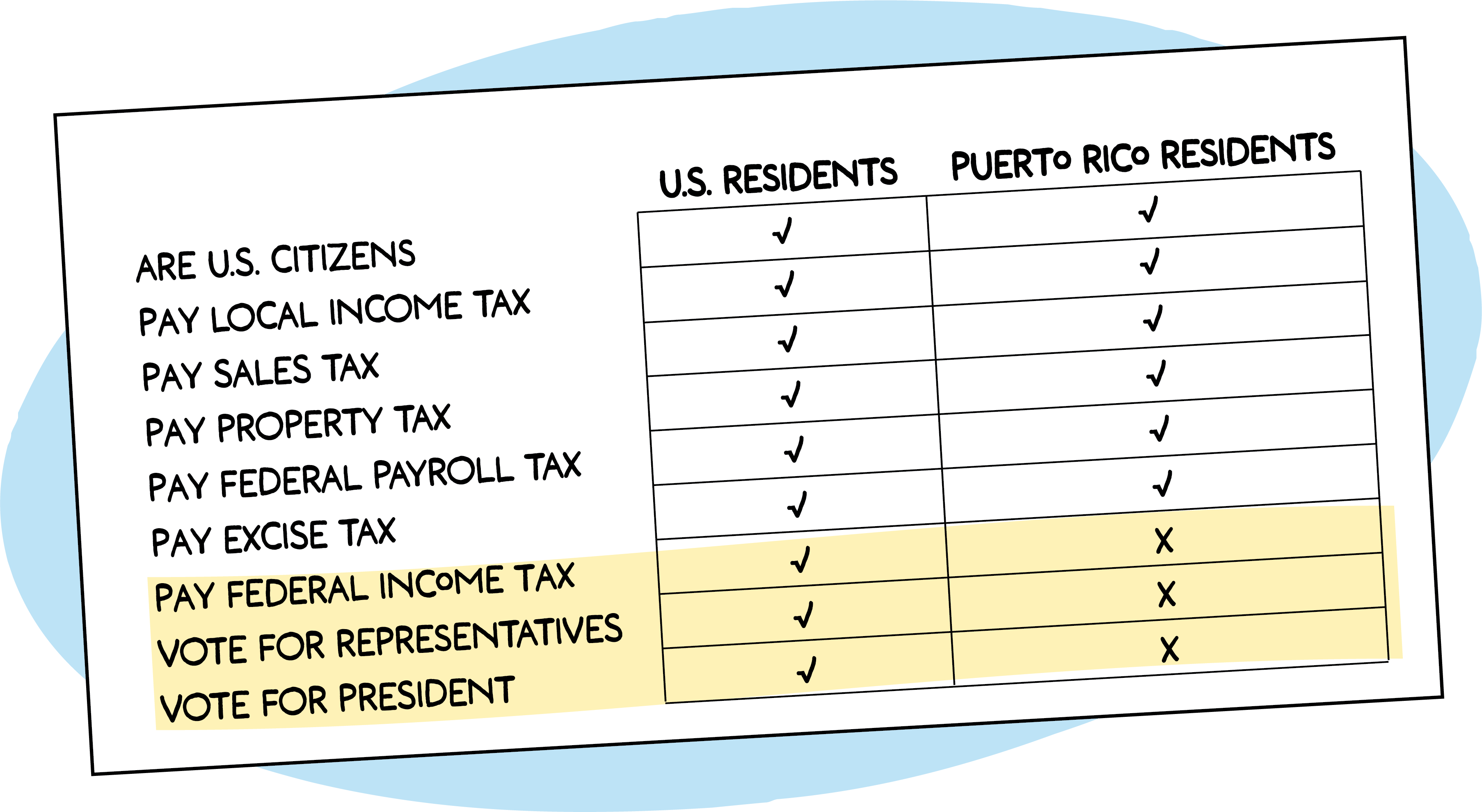

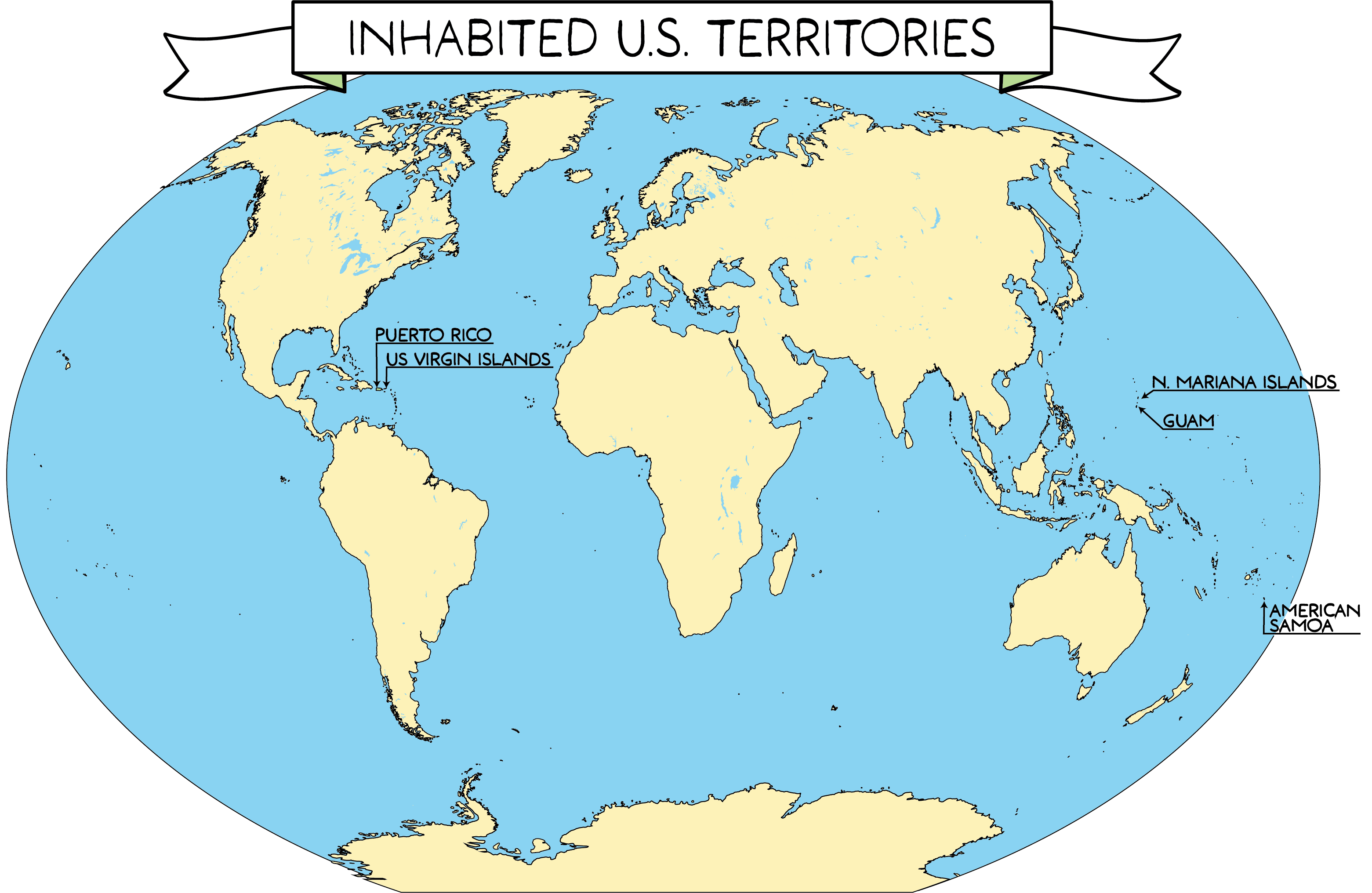

The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico is by far the most populous U.S. territory. The other four inhabited U.S. territories are American Samoa, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Unlike state residents, people in these five U.S. territories are only partially included in the federal tax system. Residents and businesses generally pay Medicare and Social Security payroll taxes, along with federal excise and business taxes, but they do not pay federal income tax.

Territories are also only partially eligible for, or entirely excluded from, major federal programs such as Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Puerto Rico residents are ineligible for the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, but the federal and territorial governments share the cost of a local EITC. Residents are partially, not fully, eligible for the federal Child Tax Credit.

To the extent territories do pay federal taxes, that’s taxation without representation. Territorial residents cannot vote in presidential elections (though they may participate in primaries), have no representation in the U.S. Senate, and are limited in the House to a single delegate per territory who cannot cast floor votes.

The Puerto Rico Tax System

With a population of about 3.2 million, Puerto Rico is larger than 18 states and the District of Columbia. Its population is nearly nine times that of the other four territories combined. Although residents do not pay federal income taxes, Puerto Rico has its own personal and corporate income taxes that are the territory’s largest source of revenue. The personal income tax is progressive; in 2024 a top rate of 33 percent applied to incomes over $61,500.

Both personal and corporate income taxes have a variety of special rates, exemptions, deductions, and credits. Puerto Rico has enacted major tax incentives benefiting multinational corporations in the name of economic development. The territory also offers significant individual tax incentives to lure wealthy mainland Americans, with mixed results. The newcomers appear to have driven up housing prices while contributing relatively little to the local economy.

Puerto Rico also has a 10.5 percent general sales tax plus a 1 percent local sales tax, producing a combined rate higher than in most U.S. states. Puerto Rico’s large liquor industry is a major source of excise tax revenue.

Puerto Rico’s 78 municipalities are authorized to levy property taxes and a tax on corporate revenue, and they receive some revenues from fees for services. Local taxes can be pre-empted by the legislature, which often authorizes tax credits that reduce municipal revenues.

Federal Control and Puerto Rican Finances

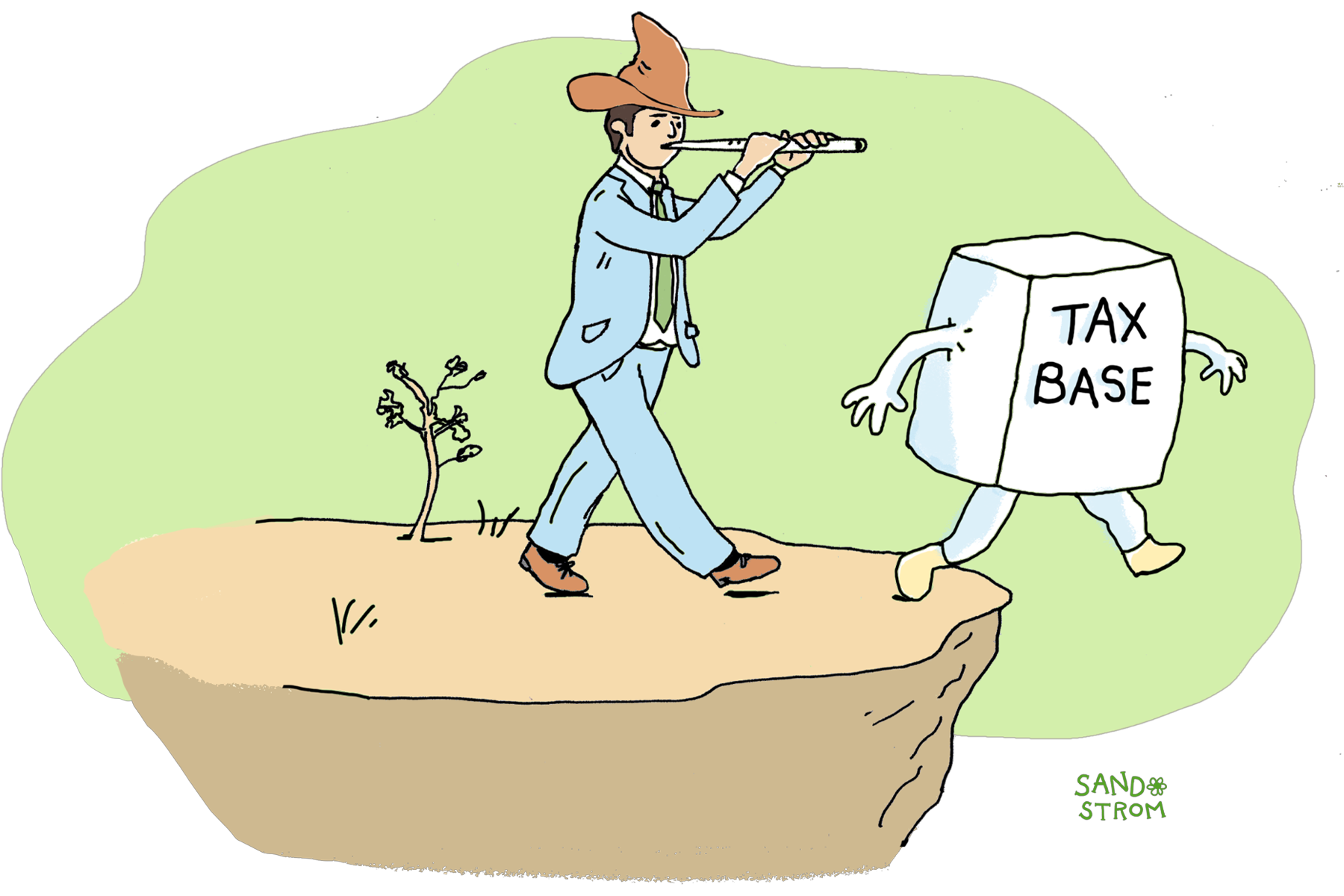

Puerto Rico’s tax treatment under federal law has contributed to its fiscal and economic problems. For many years prior to 2006, the federal government gave corporations a large tax break if they located in Puerto Rico. This policy ultimately hurt the island, because after the federal government ended the tax break, many corporations cut back their Puerto Rico operations, driving up unemployment and costing Puerto Rico significant revenues. By 2016 the territory was heavily in debt and insolvent and had no mechanism under federal law to declare bankruptcy.

The federal government then enacted the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), which created a custom bankruptcy law akin to Chapter 9 and established the Financial Oversight and Management Board, or Junta de Supervisión y Administración Financiera para Puerto Rico. “La Junta,” as it is known in Puerto Rico, has broad powers to oversee the territory’s bankruptcy and fiscal affairs. The board has the final say on the territory’s annual budget and operates independently of Puerto Rico law, but its work is funded by local tax dollars.

Since the start of federal oversight, Puerto Rico has restructured most of its debt. But it has not yet fully accessed the capital markets. And the bankruptcy of its public power utility remains unresolved. The territory’s public finances remain largely under austerity measures, and economic growth over the past eight years has been modest. Puerto Rico continues to recover from devastating hurricanes and earthquakes. Its energy infrastructure remains fragile, and its reliability has declined in recent years. It remains unclear when La Junta will restore local fiscal control, especially because in July 2025 the Trump Administration fired most of its members without naming immediate replacements.

Puerto Rico faces another risk. The territory has often used low rates and loose tax rules to attract both real investment and profit shifting to the island. Today, Puerto Rico is considered one of the largest tax havens in the world, and also among the poorest. As a result, it is now in the crosshairs of global efforts to curtail tax sheltering, such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s initiative known as “Pillar Two.” As a territory rather than an independent nation, Puerto Rico is not directly represented in the negotiations over Pillar Two, a further consequence of its colonized history.

Taxes in the Other Four Territories

The other four U.S. territories are much smaller than Puerto Rico. Three of them, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands, utilize a “mirror code” tax system, meaning their local income tax laws closely align with the U.S. Internal Revenue Code (IRC). Residents in these territories generally pay the same income tax as they would pay to the IRS if they lived on the mainland, but the revenues go to the territorial government. American Samoa similarly levies an income tax closely modeled on the federal IRC. While this provides a greater degree of tax progressivity than some states, these territories are partially or fully excluded from important federal programs. That makes them vulnerable to changes in federal law over which they do not have control.

In short, all five U.S. territories have partial autonomy and some progressivity in their tax codes. Ultimately, though, their finances are controlled by a distant federal government in which their residents lack democratic representation, undermining the core taxation principle of accountability.

Related Entries

What Principles Should Guide State and Local Tax Policy?

State and local taxes exist primarily to fund schools, roads, health care, and other services needed for communities to thrive. There are multiple ways to achieve this goal, so it can be helpful to evaluate different options based on a few core principles.

How Do State and Local Tax Systems Affect Racial Justice?

State and local tax codes have the potential to either narrow or widen racial inequality created by historical and current injustices in public policy and in broader society. In general, tax codes that are more progressive across the economic spectrum do more to narrow racial inequality, while regressive tax policies exacerbate it.

Do Tax Cuts Fuel Growth?

Tax policy is an important economic tool, but claims that tax changes will affect a state’s economy are often overstated. Such overstated claims are particularly common in discussions of taxes on wealthy individuals and profitable corporations, so careful assessment of such claims is an important part of shaping adequate and equitable revenue streams.

Learn More

- Acevedo, Nicole (2023). “Do Puerto Rico tax breaks displace locals to benefit the wealthy?” NBC News.

- Balmaceda, Javier (2025). “Puerto Rico Needs and Should Have Full and Equitable Access to All Federal Economic and Health Security Programs.” Testimony before the Puerto Rico Advisory Committee of the United States Commission on Civil Rights. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- Citizens for Tax Justice (2016). “Puerto Rico and Section 936: A Taxing Lesson from History.”

- Espacios Abiertos (accessed 2025). “Fiscal Oversight Board.”

- Espacios Abiertos (2024). “Global Minimum Tax and Its Potential Effects in Puerto Rico: A Window of Opportunity.”

- Joint Committee on Taxation (2012). Federal Tax Law And Issues Related To The United States Territories.

- López Paleo, Alexis (2022). Tax Expenditures in Puerto Rico: Internal Challenges and Global Perspective. Espacios Abiertos.

- Meléndez-Badillo, Jorell. Puerto Rico: A National History. Princeton University Press, 2024.