Online shopping is hardly a new phenomenon. And yet states and localities still lack the authority to require many Internet retailers to collect the sales taxes that their locally based, brick and mortar competitors have been collecting for decades.

This could soon change, however, now that the Supreme Court is only days away from hearing arguments in South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc. If the Court upholds South Dakota’s law, which requires sales tax collection by any out-of-state retailer with a meaningful volume of sales in the state, the decision will kick start a flurry of legislative activity that could reach all levels of government: federal, state, and local. This activity will take at least five different forms:

- States will begin requiring out-of-state retailers to collect sales taxes. Most states have enacted laws that chip away at the problem of uncollected sales taxes by requiring a growing number of e-retailers to collect the tax. But fewer have been as bold as South Dakota in enacting sweeping sales tax collection requirements that run counter to the Supreme Court’s 1992 decision in Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, which limited mandatory tax collection to companies with a “physical presence” in the state. If the Court’s ruling in Wayfair later this year reverses the Quill decision, as is widely expected, virtually every state is likely to follow South Dakota’s lead with collection requirements for every Internet retailer with a meaningful amount of sales (in South Dakota’s case, the law applies to e-retailers with at least 200 in-state sales, or $100,000 worth of in-state-sales). In many states, this may simply involve updating official guidance to clarify that e-retailers are required to collect sales tax. In other states, a change in law may be needed to ensure that the sales tax will be broadly collected by out-of-state companies, not just in-state businesses.

- States will require online marketplaces to collect and remit taxes on behalf of smaller, third-party sellers. A large and growing number of online sales are made by smaller sellers working in partnership with larger online marketplaces managed by companies such as Amazon, Etsy, and even Walmart. But sales taxes are rarely being collected on the sales—as President Trump has pointed out repeatedly in recent weeks. For these types of sales, the simplest and most enforceable approach is to require the company that owns the marketplace to collect and remit sales taxes for all the sellers using that marketplace. Washington State and Pennsylvania have already implemented this approach successfully, with Amazon and other companies starting marketplace sales tax collection earlier this year. Other states taking this approach include Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and South Carolina. Lawmakers in Hawaii, Iowa, Kansas, New Mexico, and New York have also discussed the idea this year. While it is not yet clear what, if anything, the Court will have say about online marketplaces in particular, it is very likely that more states will pursue mandatory marketplace tax collection should the Supreme Court overturn Quill.

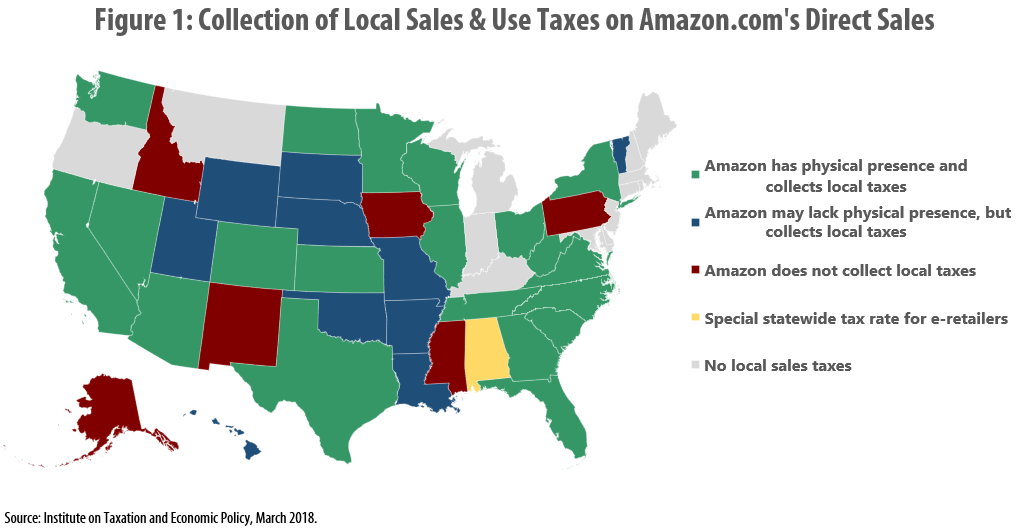

- Local governments, in partnership with state lawmakers, will close gaps in local tax collection. Online sales tax enforcement is often described as a state policy issue. But many localities also rely heavily on sales tax revenues to fund critical local services, and new ITEP research revealed that some of those localities are unprepared to collect any sales tax on purchases made from out-of-state Internet retailers. A combination of both state and local policy changes—including implementing local “use taxes” and “destination-sourcing,” where the tax charged is based on the location of the buyer, rather than the e-retailer’s warehouse—will be needed to remedy this problem. The states identified in ITEP’s report as needing to act are Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Mississippi, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania.

- Federal lawmakers may require states and localities to simplify sales tax administration, and those states and localities will take steps to do so. For years, Congress has contemplated allowing states and localities to require sales tax collection by out-of-state online retailers, on the condition that they take steps to make tax calculation, collection, and remittance simpler for sellers. But bills such as the Remote Transactions Parity Act (RTPA) and the Marketplace Fairness Act (MFA) have repeatedly failed to advance, partly because of inaccurate claims that the bills create a “new tax.” Congress’s lack of enthusiasm for this issue could change very quickly, however, if the Supreme Court eliminates the “physical presence” requirement and states are suddenly able to apply their sales tax collection laws to a much larger number of online retailers. Under this scenario, the RTPA and the MFA may be seen as reining in state and local taxing powers, rather than expanding them, and their likelihood of passage could increase as a result. If either of these bills is enacted, states will move quickly to meet the simplification requirements, which include creating uniformity across state and local tax bases and ensuring that online retailers only have to deal with one entity within each state for issues related to sales tax administration and auditing. And even if federal legislation does not make it to President Trump’s desk, states and localities may still find themselves having to enact laws to fulfill any simplification requirements that the Court chooses to endorse in handing down its decision in Wayfair.

- States and localities will decide how to use higher sales tax revenue collections. As online shopping has grown in popularity, the revenue loss associated with this tax enforcement gap has grown. Some states, such as Missouri and Iowa, are contemplating using the revenue gain from taxing online sales to partially fund income tax cuts, a swap likely to benefit those states’ most affluent taxpayers and worsen the upside-down nature of these states’ tax codes. South Dakota, meanwhile, has considered aiming for revenue neutrality within the sales tax itself. A proposal in that state would lower the sales tax on groceries if the state begins collecting additional revenue from online sales. Many other states and localities are likely to use the revenue gain to cope with challenging budget situations that have been created in part by shrinking sales tax bases. The governors of New Jersey and New York, for instance, have included revenue from taxing online sales in their budget proposals. This last option is the best one for states that have seen their revenues eroded by economic changes, such as the growth in e-commerce, with which state and local tax codes have not kept pace.

The Supreme Court’s decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc. is rightly much anticipated, but it will not be the final chapter in the effort to ensure that online retailers are collecting state and local sales taxes. If the Court allows for expanded sales tax collection, lawmakers at all levels of government—federal, state, and local—will need to respond with legislative changes to make online sales tax collection a reality.