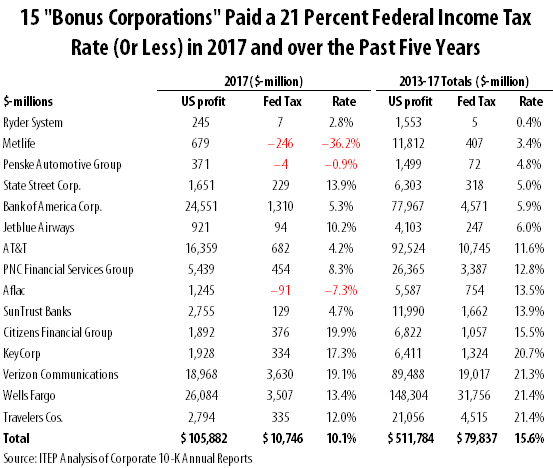

15 Major Corporations Paid Below the New 21 Percent Statutory Tax Rate in 2017 and over Five Years

Since the corporate tax cut took effect at the beginning of 2018, a number of large corporations have announced plans to give bonuses or pay raises to some of their employees. Some of these companies have explicitly said that the new tax law, which sharply reduced the federal corporate income tax rate from 35 to 21 percent, made these moves possible. But an examination of the tax-paying habits of these corporations found that many of them used various tax breaks and accounting maneuvers to reduce their tax rates to below 21 percent year after year before the new tax law passed. In other words, claiming that the new low statutory rate of 21 percent was the incentive to give out bonuses or boost workers’ wages is, at best, inconsistent with the facts.

This report identifies 15 companies that have announced tax law-related worker bonuses, each of which paid effective tax rates of 21 percent or less both in 2017 and over the past five years.

Companies Announcing Worker Benefits Already Paid Very Low Corporate Tax Rates

Among the companies that have announced one-time employee bonuses or other worker benefits in the wake of the tax bill’s passage are a number of corporations for which the former 35 percent corporate tax rate was little more than an abstraction:

- The Ryder Corporation announced one-time employee bonuses totaling $23 million. But Ryder has been virtually untouched by the federal income tax for half a decade: Ryder’s tax rate in 2017 was just 2.8 percent, and over the past five years it has paid an effective tax rate of just 0.4 percent on $1.5 billion of S. income.

- Insurance giant Metlife announced that it will increase its hourly minimum wage to $15, “as a result of tax reform.” But in 2017, the last year under the old tax rules, Metlife paid no federal income taxes on $679 million of S. profits, and paid just a 3.4 percent tax rate over the past five years—just one-tenth of the 35 percent statutory rate that somehow prevented the company from appropriately paying its workers in prior years.

- Auto parts maker Penske Automotive disclosed that it paid no federal income taxes on $371 million of S. profits in 2017 and paid just 4.8 percent of its profits in federal income taxes over five years. Yet the company claims the tax bill enabled Penske to expand its program of matching employer contributions to retirement accounts.

- The telecom firm AT&T said it would give $1,000 worker bonuses to 200,000 workers because the tax bill brought the S. corporate tax rate “in line with the rest of the industrialized world.” But AT&T paid just 4.2 percent of its U.S. profits in federal income taxes last year, far below effective rates in other industrialized countries.

As a group, these 15 companies paid a federal income tax rate of just 10 percent on $105 billion of U.S. profits last year and paid a 15 percent tax rate on half a trillion dollars of profits over the past five years. This means that these companies collectively were able to avoid tax on over half of their profits during the past five years. All 15 companies’ effective federal income tax rates for 2017 and the five-year period between 2013 and 2017 are shown in the table below.

Corporate Bonus Announcements Are Likely A Public Relations Ploy, Not a Response to Tax Cuts

Mainstream economists overwhelmingly agree that the primary corporate response to income tax cuts will be a wave of stock buybacks. This was the most obvious consequence of the last sizeable corporate tax cut enacted by Congress in 2004, and so far this year, stock buybacks have reached record level, prompting one Forbes headline, “Why It’s Raining Share Buybacks on Wall Street.” The corporate tax cut enacted last December came at a time when most large companies, riding a historic wave of profitability, already had sufficient cash in hand to engage in any human capital investments they chose to. While the Joint Committee on Taxation forecasts that in the long run, about a quarter of the benefits of corporate rate cuts will flow through to workers in the form of higher wages, few economists seriously claim that workers will see any meaningful wage boosts in the short run. Yet the companies profiled in this report appear to have altered their views on the need to reward their workers within weeks of the tax plan’s passage—even though the tax laws existing before the bill’s passage had a minimal effect on their cash flow.

The most likely explanation for the wave of corporate bonus announcements in the wake of the tax bill’s passage is that the leaders of these companies recognized the historic unpopularity of the 2018 tax cuts for what it was: a sign that the American public believes the new tax law will have very little lasting effect on their pocketbooks. The series of prominent bonus announcements by companies with only a passing acquaintance with the former 35 percent tax rate appears to have been designed to convince the public that, against all odds, a tax plan geared toward large corporations will actually “trickle down” to middle-income workers.

In the Long Run, Unfunded Corporate Tax Cuts Will Likely Hurt Middle Class Workers and the U.S. Economy

The corporate tax cuts embedded in the new tax law, by any accounting, will worsen the nation’s long-term fiscal imbalance, setting it on a path toward record-high public debt in the next decade. While Congress has postponed even the most basic reckoning with this long-term imbalance, in the long run lawmakers must either pare back these tax cuts or find another path to fiscal balance. Because the new tax law focuses on cutting the taxes paid by the best-off Americans, any alternative deficit reduction strategy will inevitably shift the costs onto the backs of middle-income families, either in the form of damaging spending cuts or a regressive tax shift toward consumption or payroll taxes. The one-time bonuses announced by prominent corporations this winter are little more than a smoke screen to help mask the true cost of the so-called Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.