|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overview

The United States needs to address growing inequality and raise more revenue to make public investments. One way to accomplish both goals is to enact legislation that raises taxes for high-income or high-wealth households.

This does not mean that all new taxes must only affect those at the top. It simply means that progressive tax measures are a sensible place for lawmakers to start to address these problems.

The facts and figures that follow demonstrate four points.

- The U.S. needs to address inequality.

- The U.S. needs more revenue.

- Our tax system is not solving these problems now.

- The public supports using progressive taxes to solve these problems.

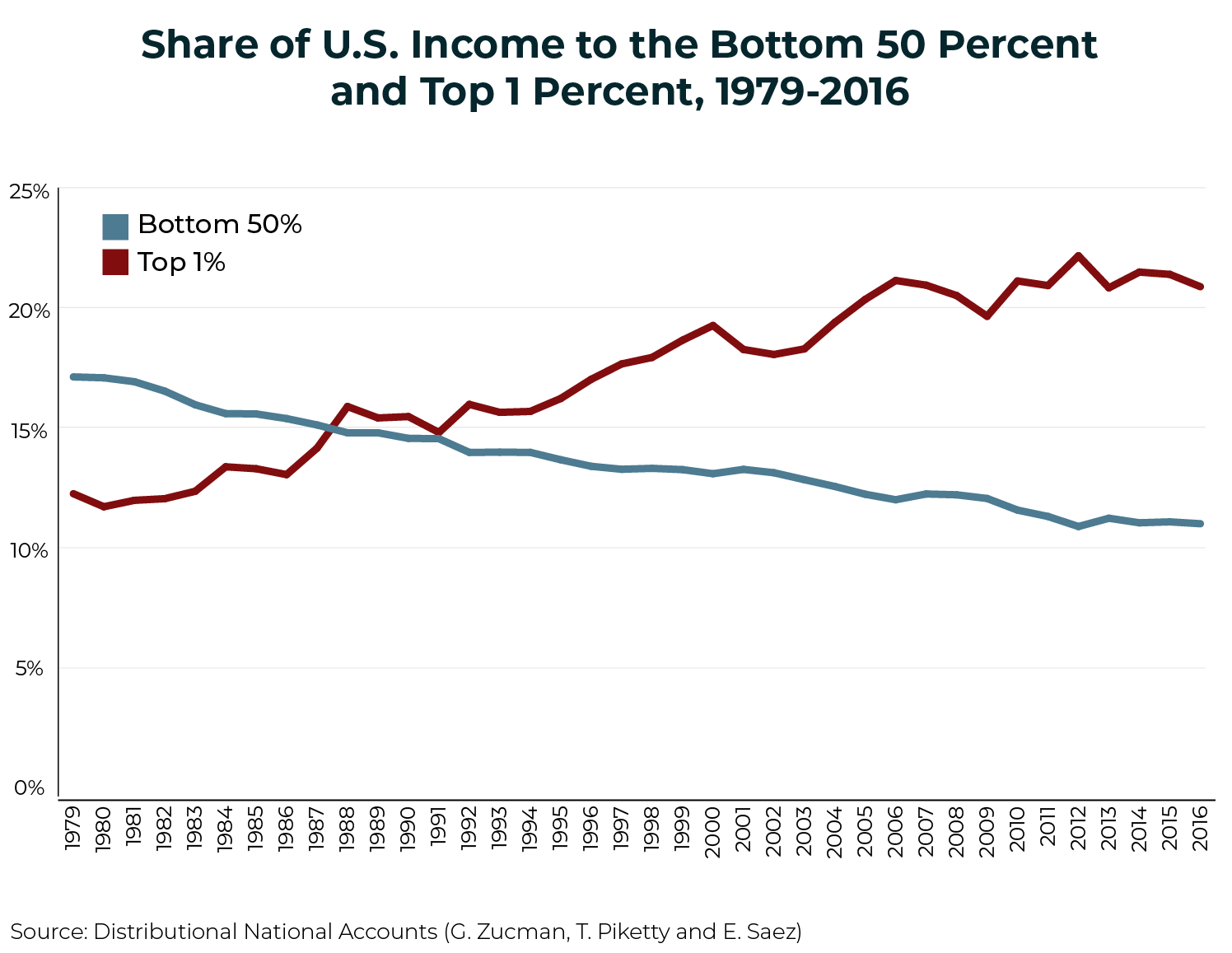

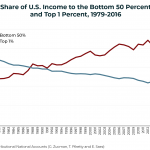

The Share of Income Going to the Rich Has Grown Substantially Over the Past 40 Years

Data from inequality researchers Piketty, Saez and Zucman show that Americans in the bottom half of the income distribution have seen their share of total U.S. income fall from 17 percent in 1979 to 11 percent in 2016.

Meanwhile, the top 1 percent of the income distribution has seen their share of total U.S. income rise from 12 percent to 21 percent over that same period.

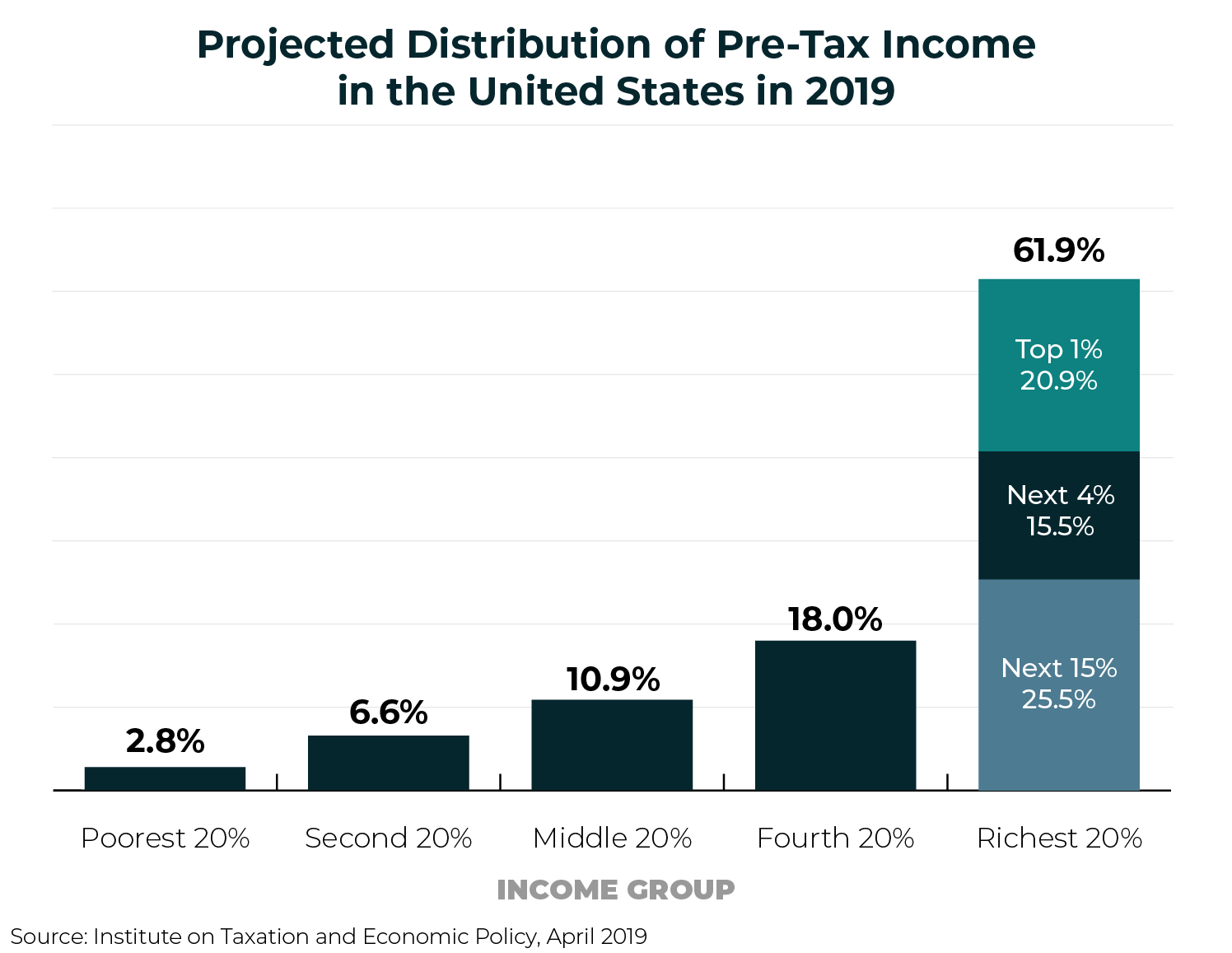

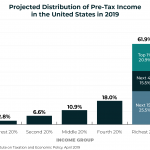

The Distribution of Income Today is Highly Unequal

ITEP projects that the richest fifth of Americans will receive about 62 percent of total income in the U.S. in 2019.

The top 1 percent alone will receive nearly 21 percent of the total income. This is more than the share of income expected to flow to the bottom 60 percent of earners combined.

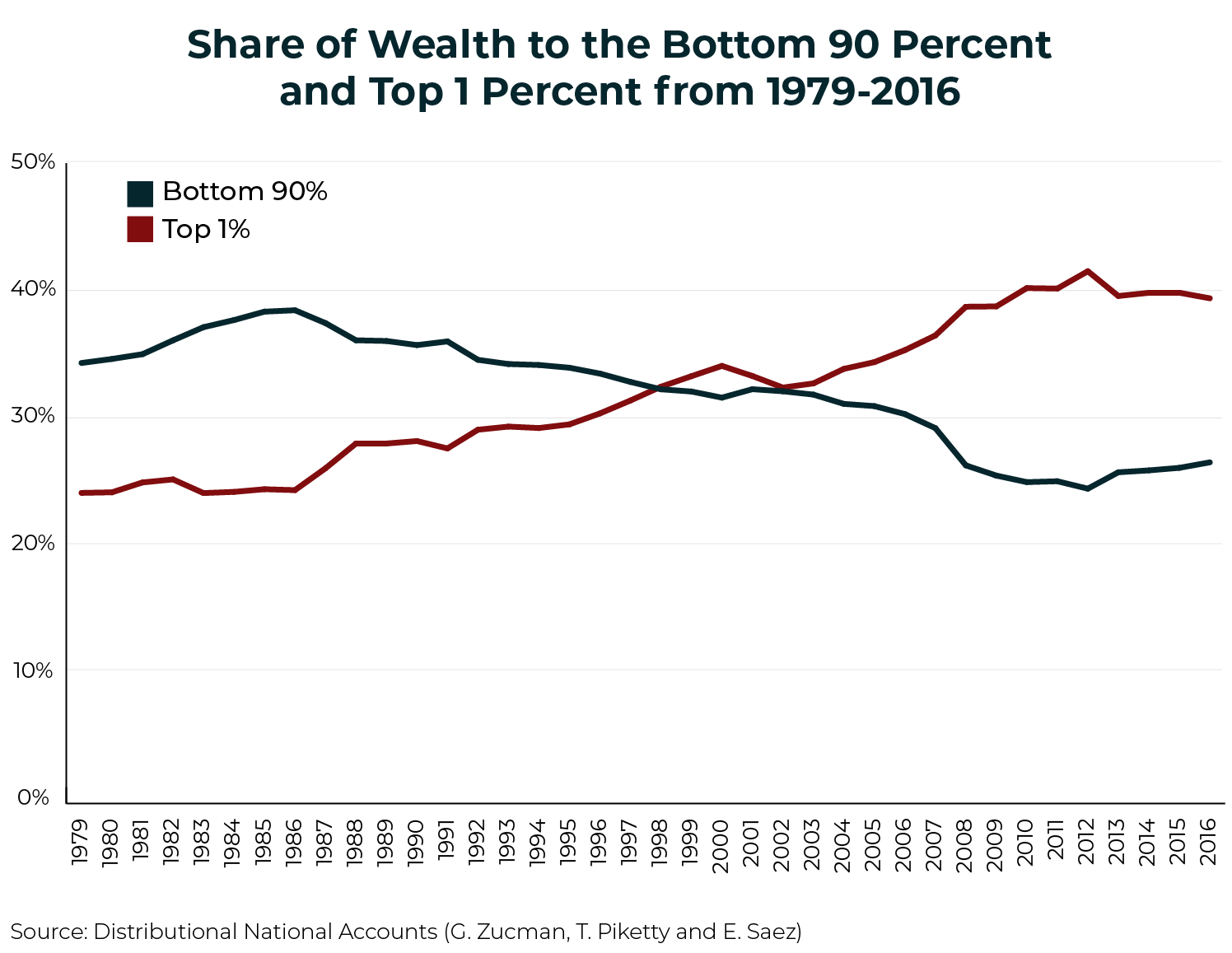

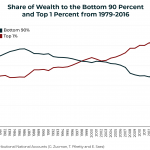

Wealth Inequality in the U.S. Is Even More Severe than Income Inequality

The top 1 percent of Americans defined by net worth have seen their share of total wealth in the U.S. rise from about 23 percent in 1979 to about 39 percent in 2016.

Meanwhile, the bottom 90 percent of Americans defined by net worth have seen their share of total U.S. wealth fall from about 34 percent in 1979 to 26 percent in 2016.

Wealth inequality is the compounded effect of years of income inequality. Reforming our income tax to eliminate special breaks for income generated from wealth is an important step toward lessening wealth inequality. Increasing the estate tax and introducing a federal wealth tax can also be part of the solution.

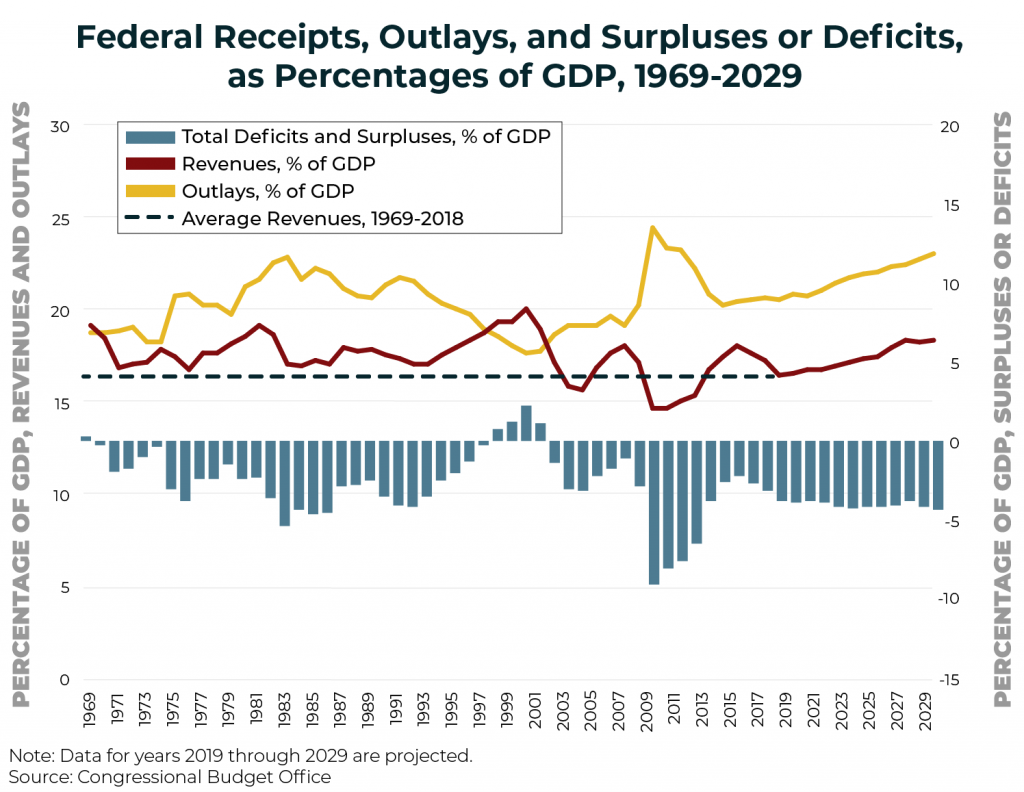

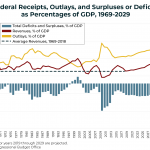

Federal Revenue Has Long Been Too Low

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), for the previous 50 years, from 1969 through 2018, the federal government collected revenue equal to 17.4 percent of the U.S. economy on average.

Today that amount has fallen below 17 percent of GDP, and CBO projects that we will not return to our previous 50-year average until the scheduled expiration of some provisions in the new tax law—provisions that some members of Congress will surely seek to extend.

But merely returning to historical average tax levels will not be enough to fund the investments that are needed to allow our economy to thrive. Federal spending has consistently exceeded 17.4 percent of GDP under both Republican and Democratic administrations.

To find lower levels of federal spending, one must look back to the 1950s and late 1940s, before the enactment of Medicare and before Social Security became a meaningful tool for improving the lives of the elderly, survivors and people with disabilities.

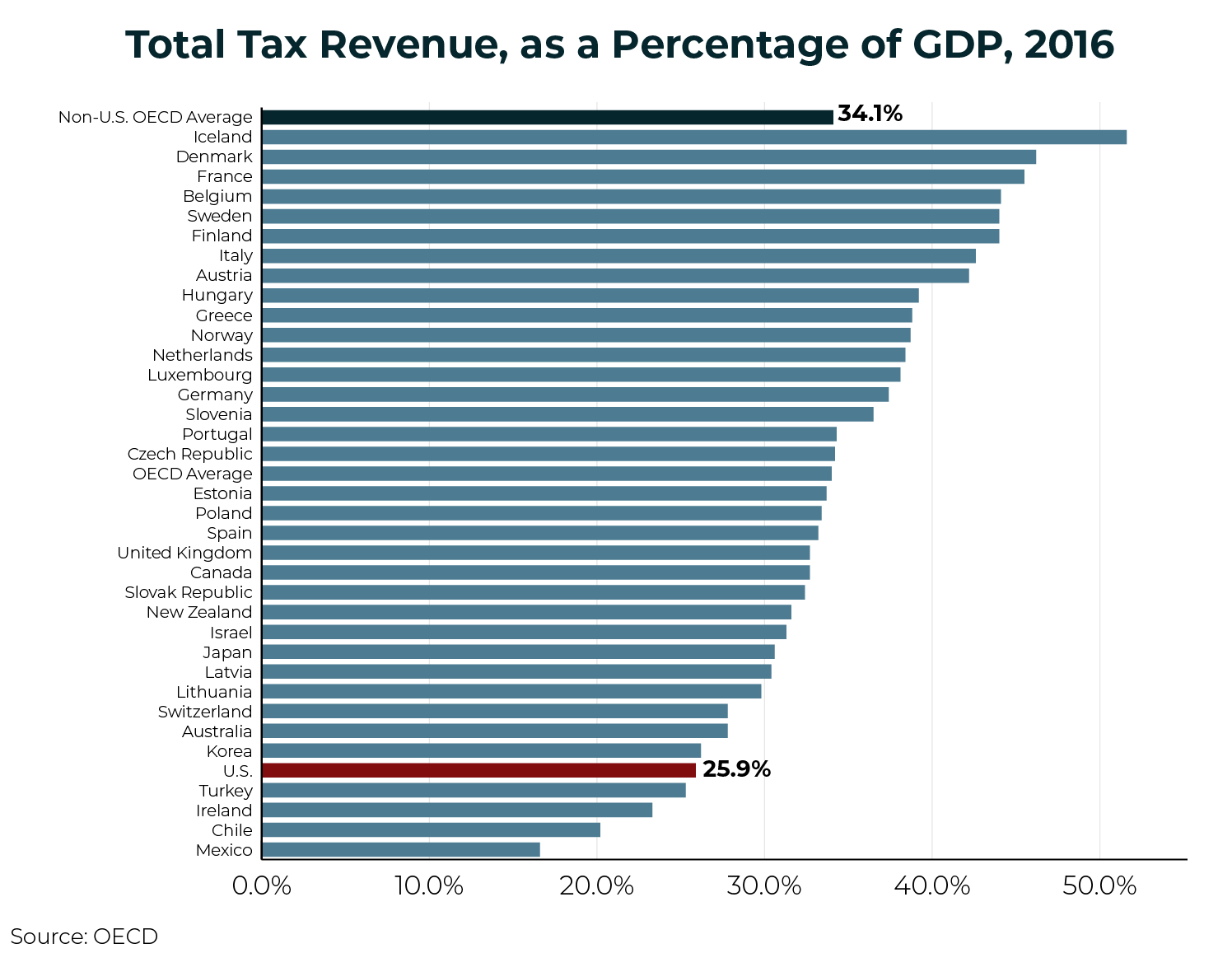

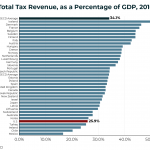

The U.S. Is One of the Least Taxed Countries in the Developed World

We see this in data from the OECD, the club of industrialized countries with which we do much of our trade.

According to the OECD, total federal, state and local revenue collected in the U.S. equals about 26 percent of our GDP, while the average for other OECD countries is 34 percent of GDP.

In this regard, the U.S. ranks 32nd out of the 36 OECD nations.

That means only four OECD countries collect less revenue as a share of their economies. Those countries are Turkey, Ireland, Chile and Mexico.

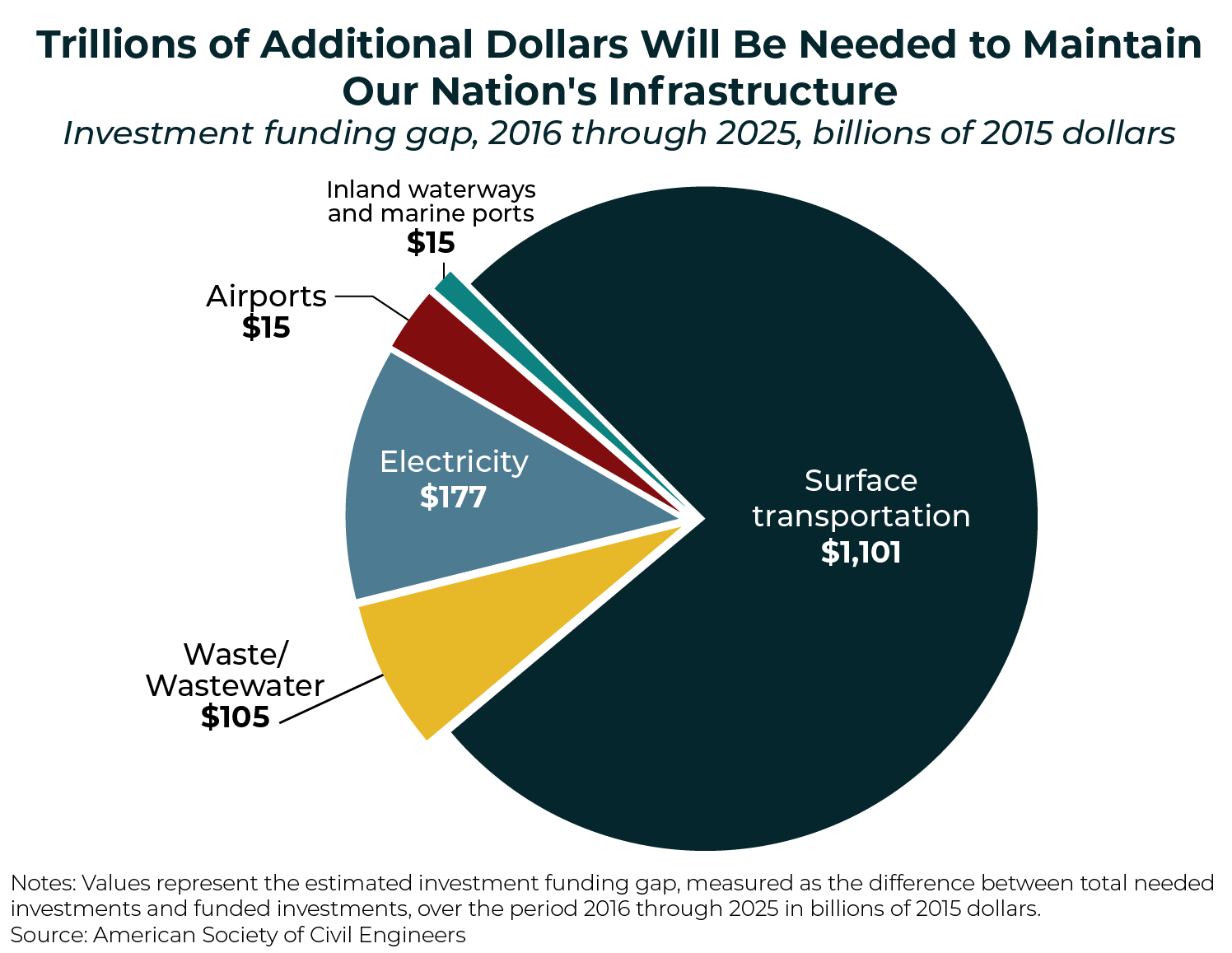

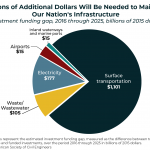

America Needs More Revenue to Adequately Invest in Public Goods

Failing to make public investments can make our economy less efficient and our nation less prosperous.

Our underfunding of public infrastructure is just one example. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) estimated that the U.S. needed to increase its infrastructure spending by $1.4 trillion from 2016 through 2025.

The ASCE estimated that leaving that funding gap in place would ultimately hurt us by reducing our GDP by $4 trillion over that period.

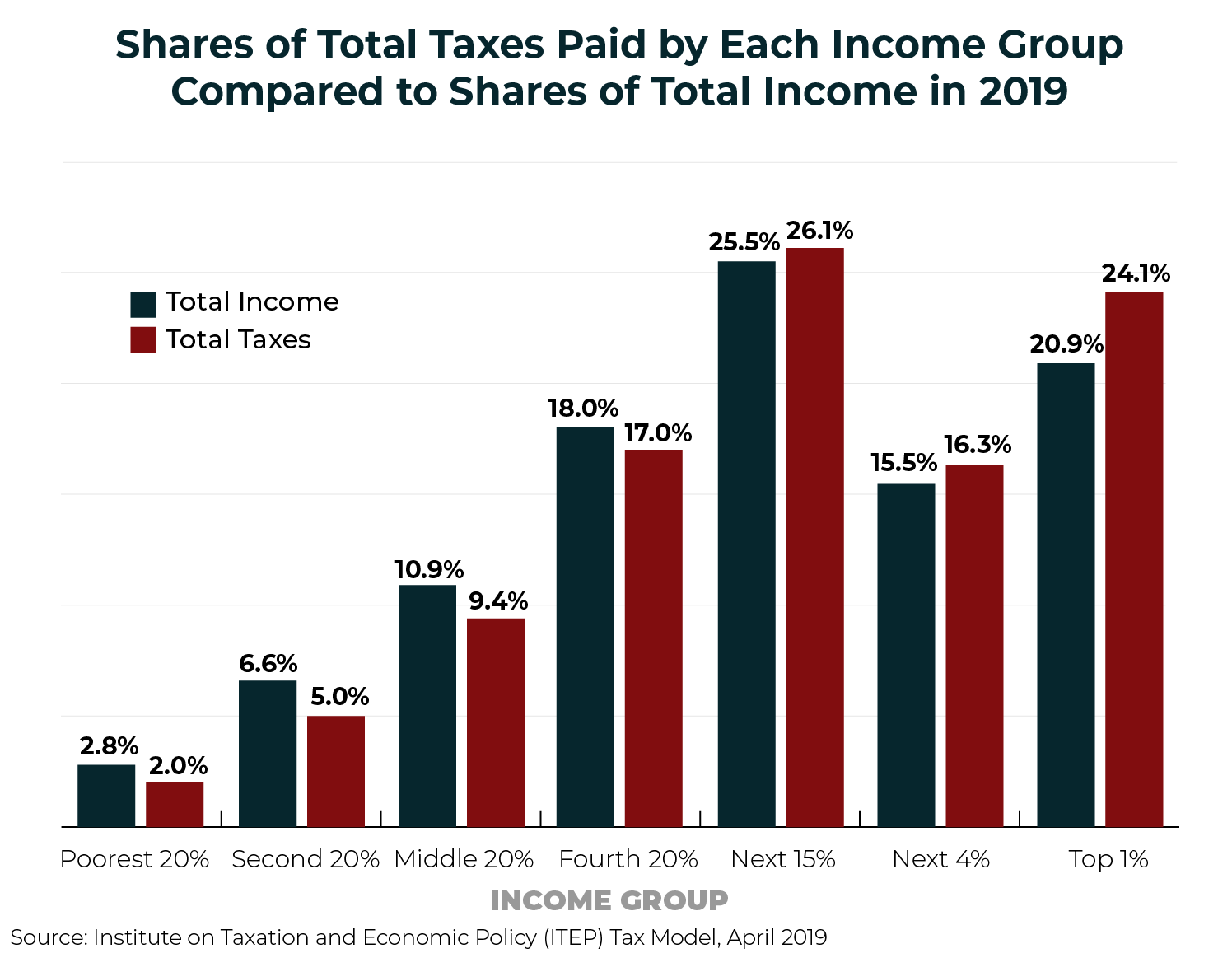

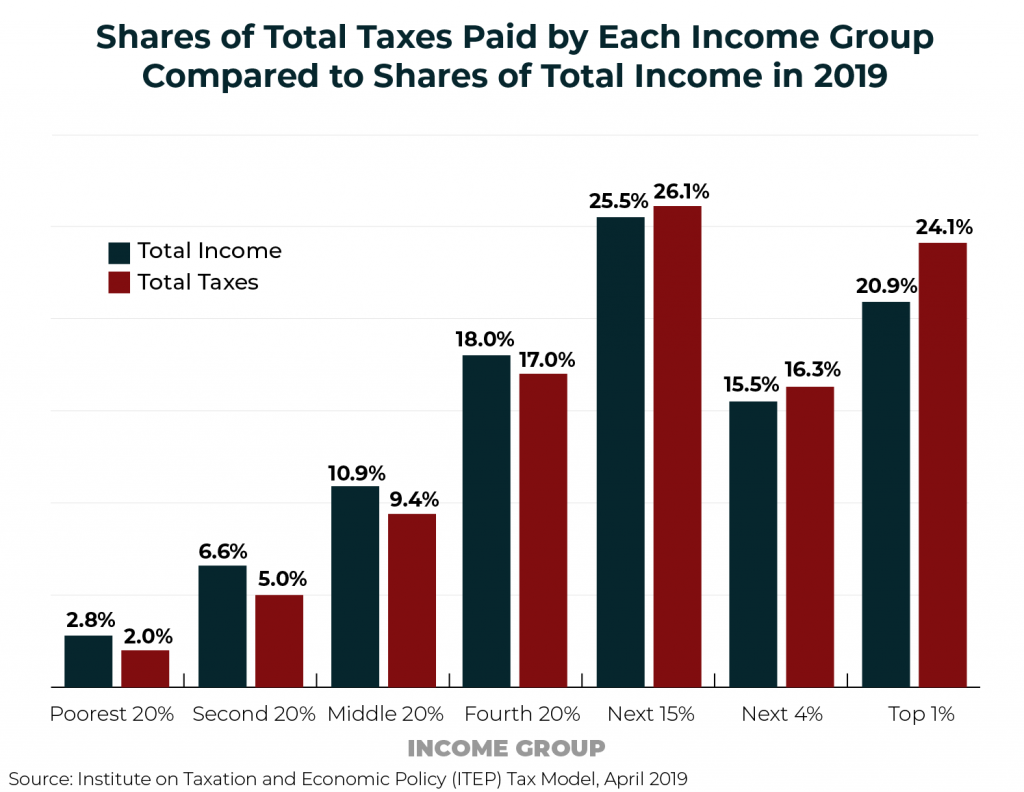

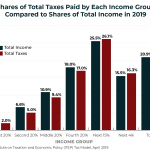

America’s Tax System Is Doing Little to Reduce Inequality

Despite faring extraordinarily well in today’s economy, the nation’s richest taxpayers are paying a share of overall taxes that only slightly exceeds their share of income.

ITEP projects that in 2019, the share of total federal, state and local taxes paid by the top 1 percent (24.1 percent) will be only slightly greater than the share of total income received by this group (20.9 percent).

While certain parts of our tax system are progressive, like the federal personal income tax, the federal corporate income tax and the federal estate tax, much tax revenue in the U.S. is raised through taxes that are not progressive.

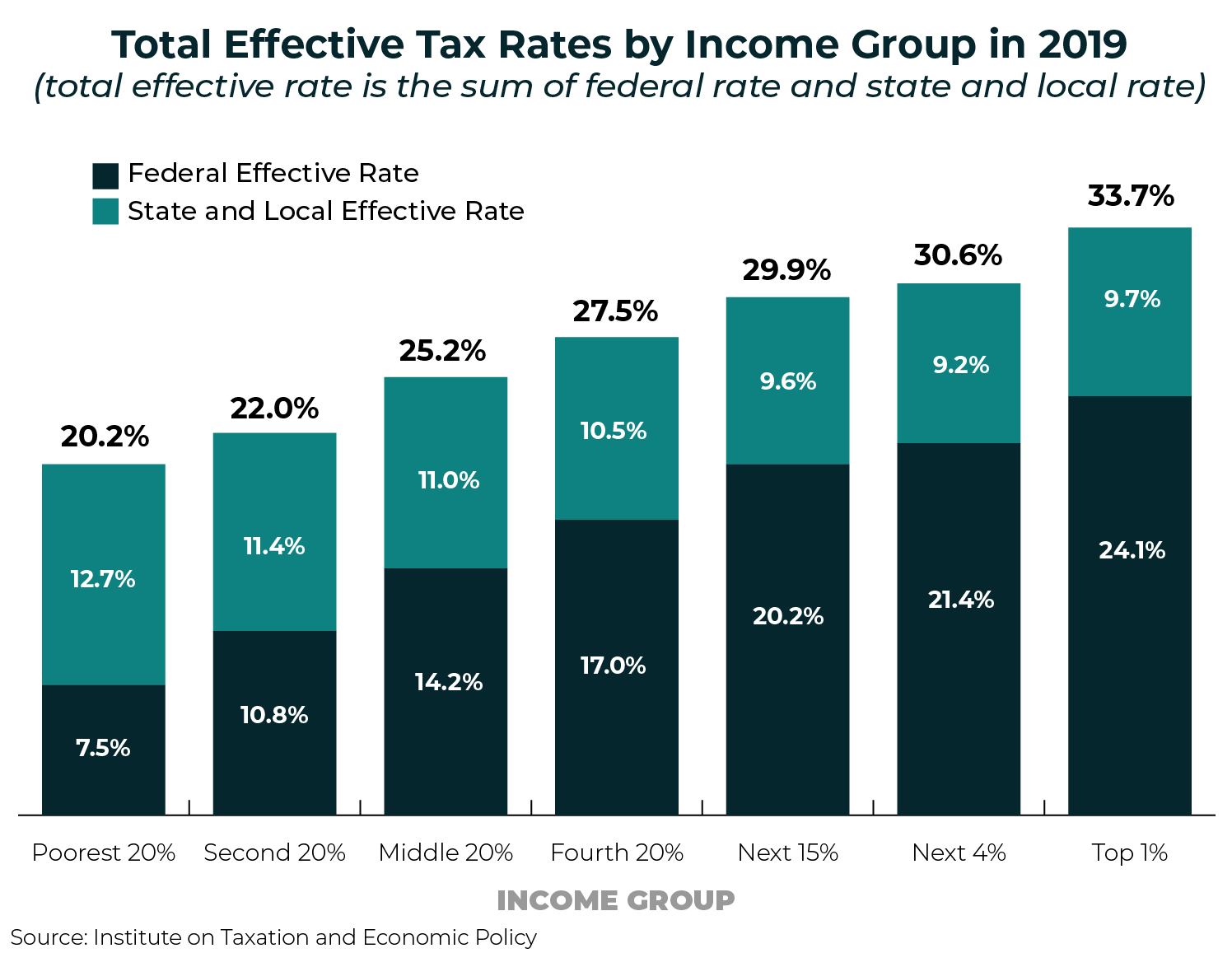

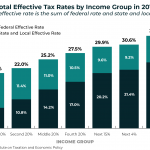

Some Parts of Our Tax Code Are Regressive

The federal tax code is progressive overall despite including some revenue sources, like payroll taxes, that are not progressive.

State and local taxes are particularly regressive, meaning they capture a larger share of income from low- and middle-income families than high-income families.

The progressivity of our federal tax code is needed to offset the regressive impact of state and local taxes.

However, the progressivity of our federal tax code is weakened by several special breaks and loopholes.

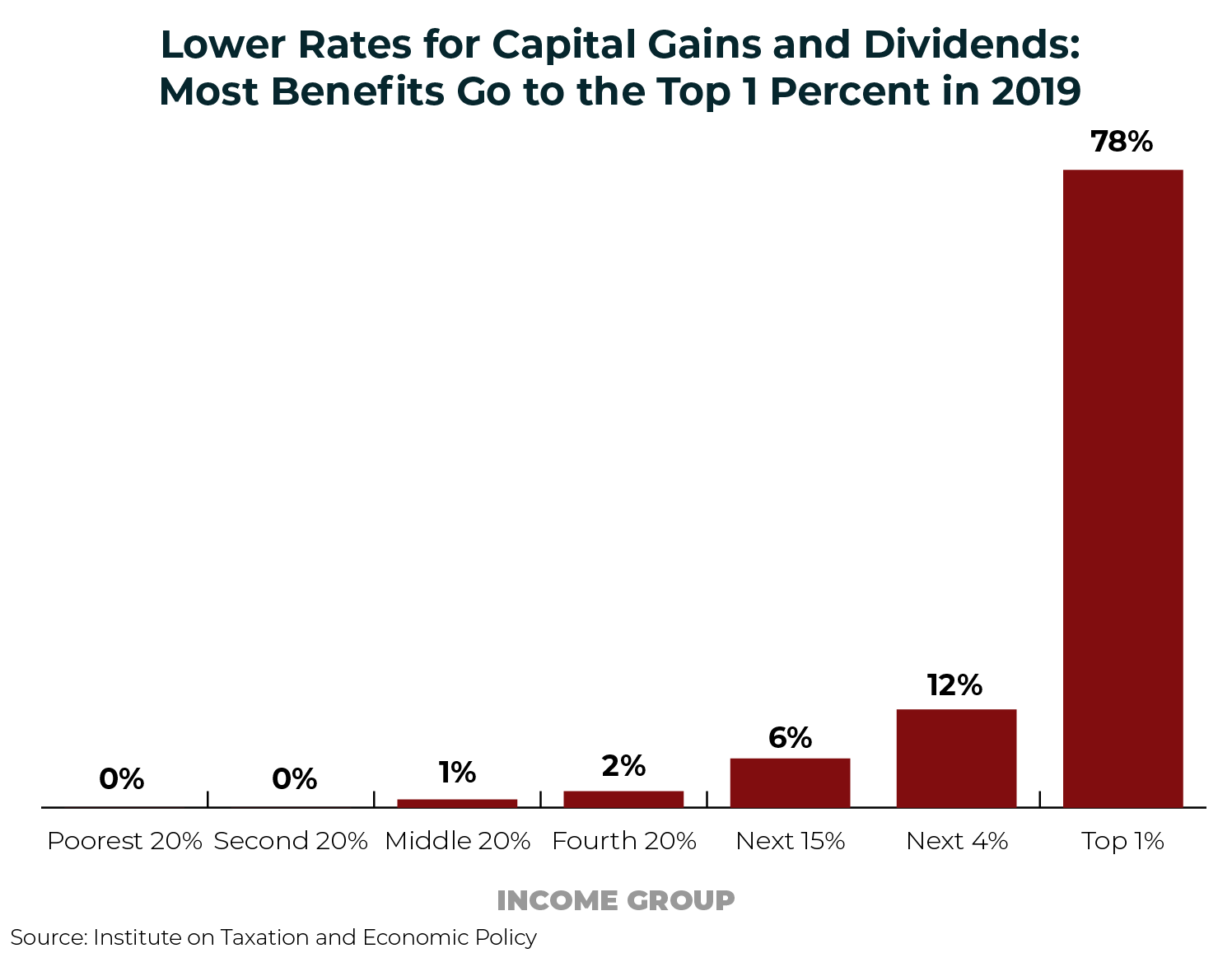

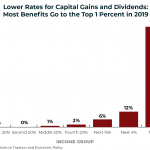

The Federal Personal Income Tax Is Weakened by Special Breaks for the Rich

One problem with the federal personal income tax is that it taxes income from wealth less than income from work.

For example, capital gains and stock dividends, which mostly go to well-off households, are taxed at lower rates than other types of income (including earned income).

As illustrated in this graph, nearly four-fifths (78 percent) of the benefits of the lower income tax rates for capital gains and dividends will go to the richest 1 percent in 2019.

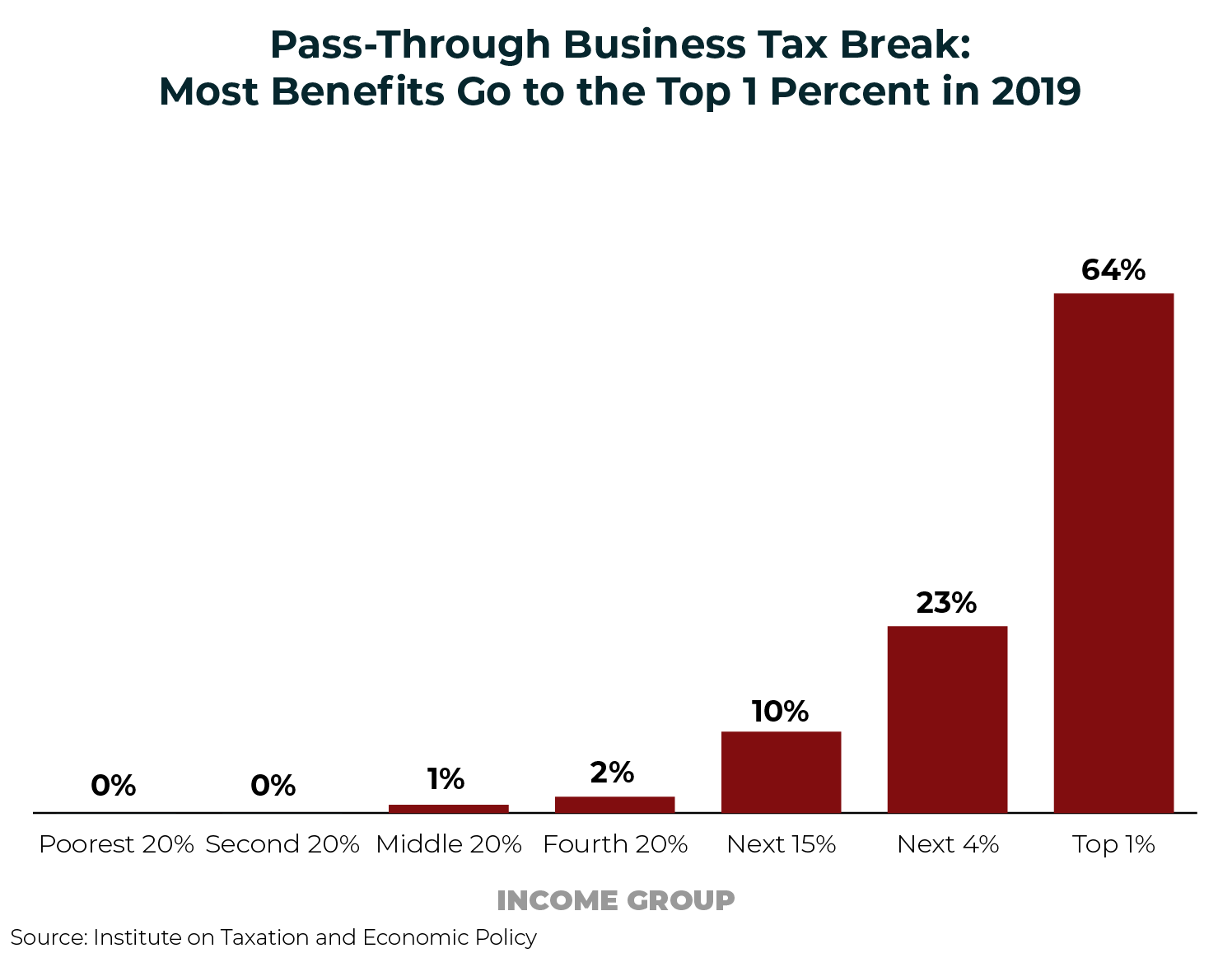

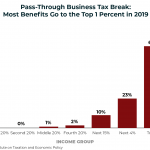

The Federal Personal Income Tax Is Weakened By Special Breaks for the Rich (continued)

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), signed into law by President Trump in December of 2017, made this problem worse.

TCJA created a tax break for another type of investment income, a deduction for profits from pass-through businesses. These are businesses whose profits are subject to the personal income tax but not the corporate income tax.

As illustrated in this graph, the vast majority of the benefits of the new pass-through deduction go to the richest 1 percent.

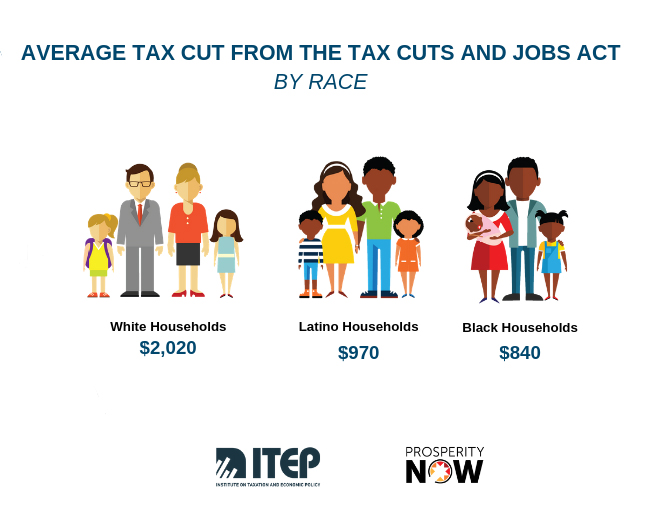

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Supercharges the Racial Wealth Divide

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act not only added fuel to the challenge of growing income inequality, it also exacerbated the racial wealth gap.

Of the $275 billion in tax cuts the TCJA provides to individuals this year, $218 billion (80 percent) goes to White households. On average, White households will receive $2,020 in cuts, while Latino households will receive $970 and Black households receive $840.

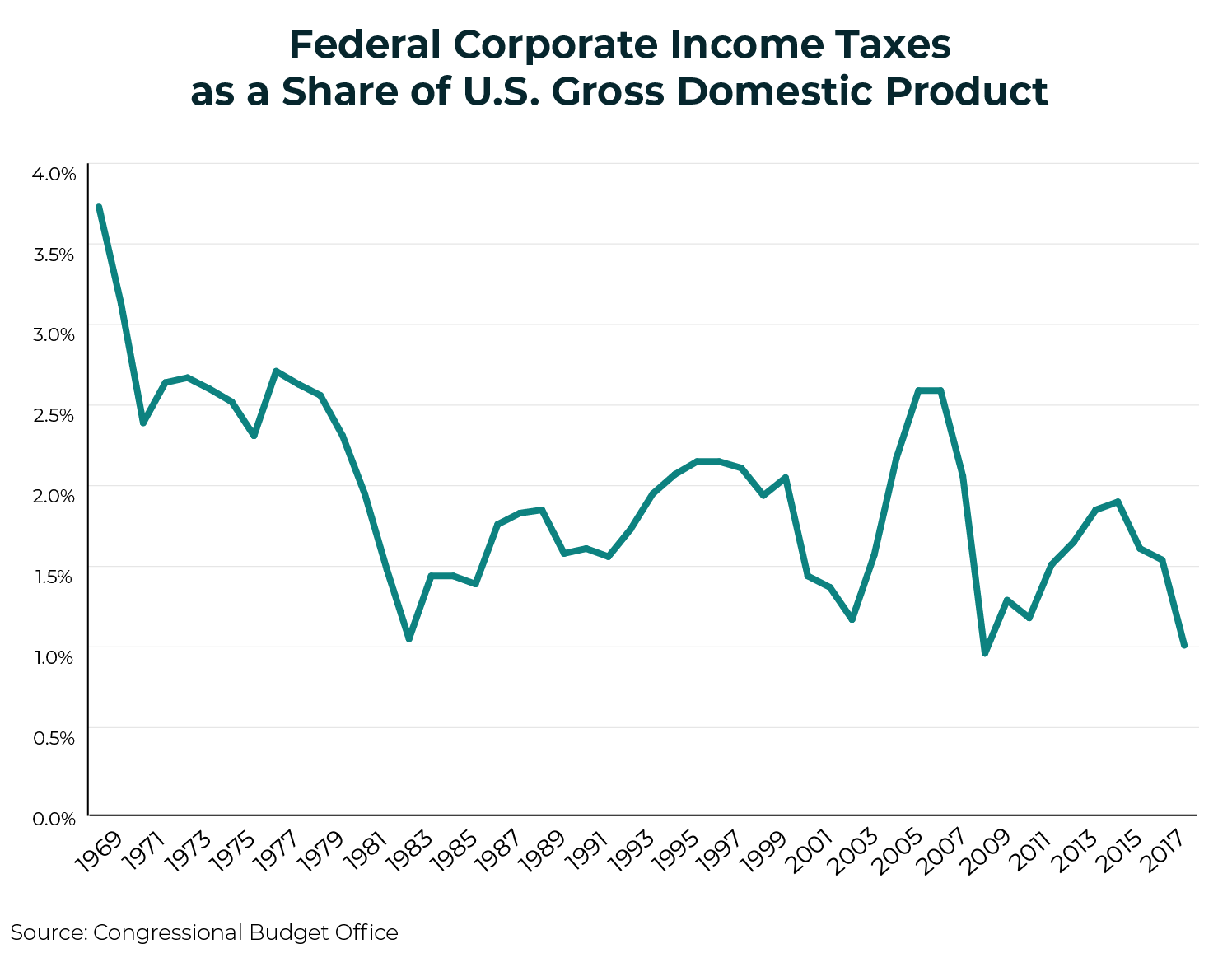

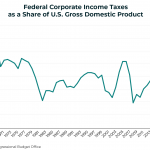

The Federal Corporate Income Tax Is Weakened By Special Breaks

The federal corporate income tax has been eroded by years of imprudent policy decisions and lawmakers’ unwillingness to crack down on corporate tax avoidance.

In 1969, the federal government collected corporate tax revenue equal to 3.7 percent of our gross domestic product (GDP). By 2018, that figure had fallen to just 1 percent of our GDP.

While many historical dips in corporate tax revenue were clearly the result of economic downturns, the current dip is being driven by large corporate tax cuts in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).

The Federal Corporate Income Tax Is Weakened By Special Breaks (continued)

TCJA reduced the federal statutory corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent.

But the law left in place most of the significant special breaks and loopholes that allow corporations to pay an effective rate that is much lower than the statutory rate.

TCJA even expanded some of those breaks, for example by expanding accelerated depreciation, which allows companies to write off the costs of capital investments much more quickly than they actually wear out.

The public disclosures that corporations have made for 2018 already indicate that several of them avoided paying federal income taxes altogether during their first year under the new law.

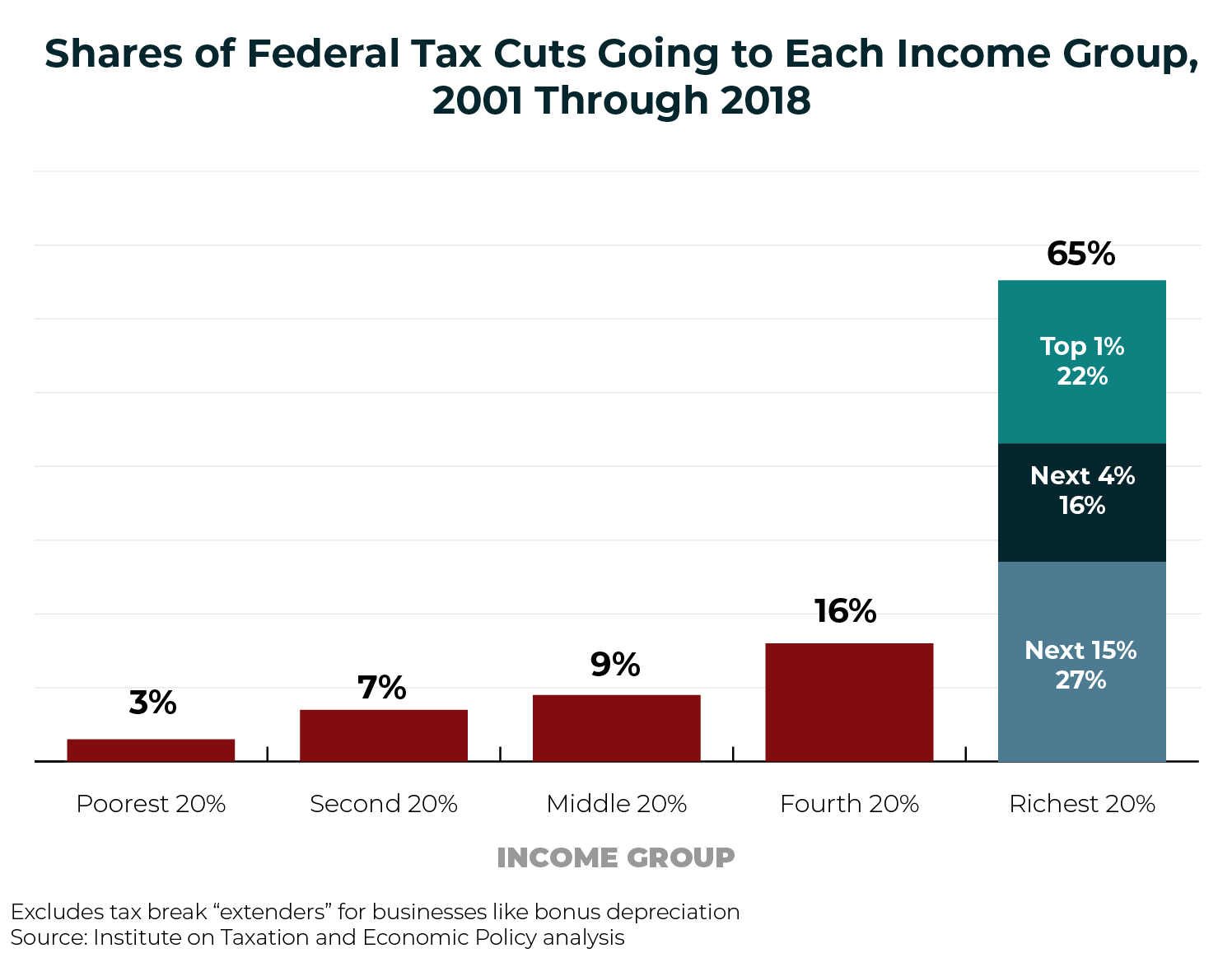

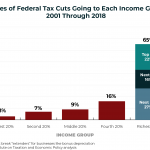

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Was Only the Latest Big Tax Cut for the Well-Off

The major tax laws enacted by Congress and several presidents since 2000 have reduced revenue by $5.1 trillion, with nearly two-thirds of that amount flowing to the richest fifth of Americans. The cumulative impact on the deficit during this period is $5.9 trillion, including interest payments.

Assuming no further legislative changes, by the end of 2025 the tally of tax cuts will grow to $10.6 trillion. By then the total impact on the deficit will be $13.6 trillion, including interest payments.

Time and again, federal tax law changes have worsened both the fairness and adequacy of our federal tax system, thereby exacerbating income inequality and worsening our nation’s fiscal standing.

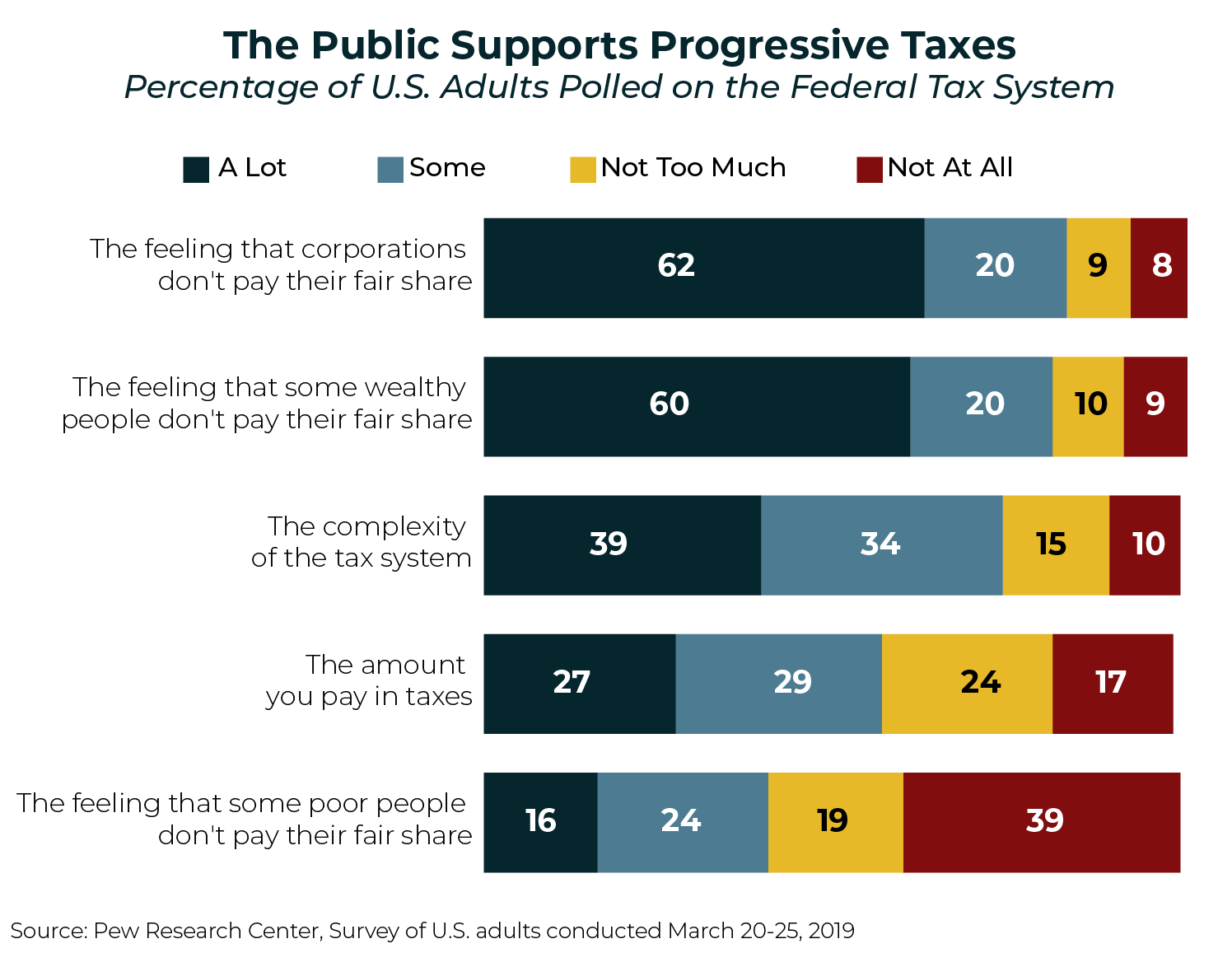

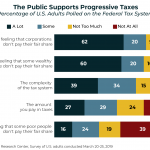

Americans Want Progressive Taxes More than They Want Tax Cuts for Themselves

There is a widespread understanding among the American public that our tax system is not asking enough of those at the top.

More than four in five Americans say they are bothered by corporations and wealthy people not paying their fair share. A strong majority (60 percent or more) say that this bothers them “a lot.”

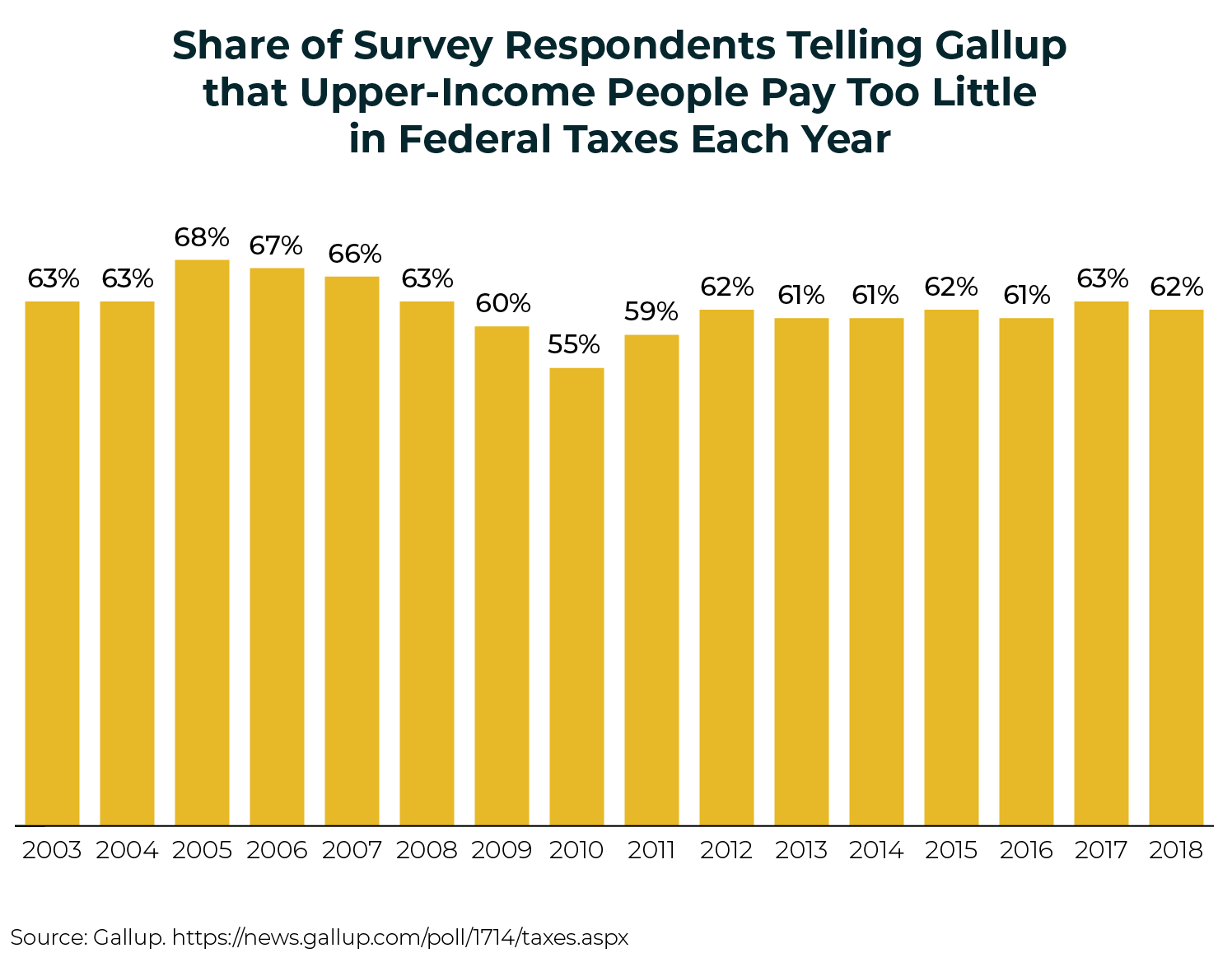

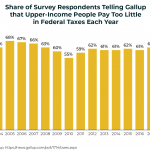

Support for Progressive Taxes Is Not New

Americans have been telling pollsters for years that they want higher taxes on high-income households and on corporations.

To the extent that the national dialogue has shifted in favor of more progressive taxes, this is not driven by a change in public opinion, but rather by the fact that there are now some lawmakers who are responding to the long-held views of the public with serious proposals.

Conclusion

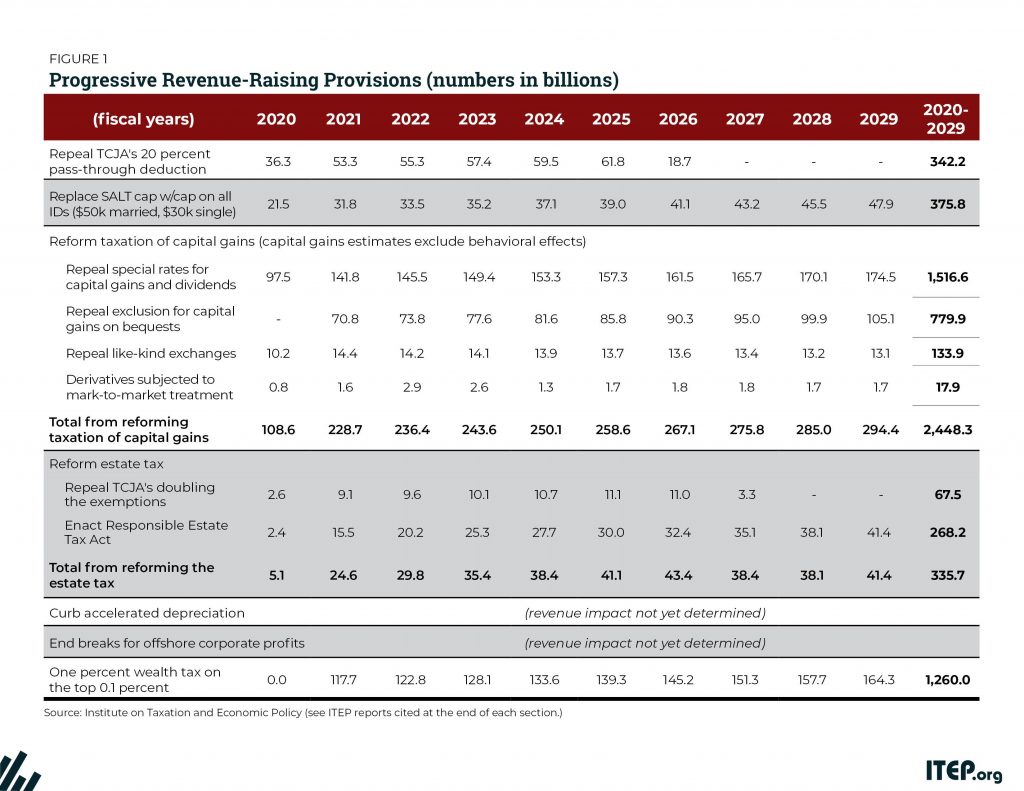

- Our tax code is raising insufficient revenue and doing too little to address widening gaps in both income and wealth.

- These problems with our tax code are not inevitable. They are choices that our lawmakers have made and that the public largely opposes.

- Congress has several options to address these problems by raising more revenue in progressive ways.

- For more on this subject, see ITEP’s report, Progressive Revenue-Raising Options.