This month marks the five-year anniversary of the first legal, taxable sale of recreational cannabis in modern U.S. history. After decades of speculation about what taxing cannabis might mean for state and local coffers, the true revenue potential of cannabis taxes is finally coming into focus. And just in time. This year lawmakers in Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont will all be debating the taxation of recreational cannabis. A new ITEP report reviews the track record of recreational cannabis taxes thus far and offers recommendations for structuring cannabis taxes to achieve stable revenue growth over the long haul.

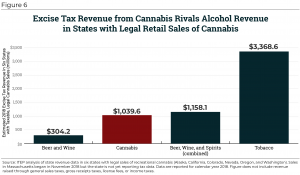

As the report shows, half a dozen states generated a combined total of more than $1 billion from their excise taxes on cannabis in 2018—a 57 percent increase relative to one year earlier. Colorado and Nevada are already raising more revenue from excise taxes on cannabis than from excise taxes on alcohol, and the same is projected to occur in California by 2020.

But while cannabis tax revenues are proving meaningful thus far, most states allowing for the legal sale of recreational cannabis have set themselves up for long-run revenue disappointments. Six of the nine states with tax structures in place are choosing to tax cannabis based solely on its price. But the experiences of Colorado, Oregon, and Washington—the three states that have been taxing cannabis the longest—make clear that cannabis prices will decline significantly in the years following legalization as legal businesses learn to operate more efficiently and as the legal barriers that had inflated the price of cannabis come down.

In Colorado, for instance, wholesale cannabis prices are already down 61 percent relative to their 2015 peak and experts have forecast that the price could fall much lower—particularly if the federal government lifts its ban on the substance. So far cannabis sales in Colorado have grown rapidly enough that falling prices have yet to trigger a revenue decline. But when the industry matures and sales stabilize, states such as Colorado will find that the yield of their cannabis taxes will be closely intertwined with the plummeting price of cannabis.

To avoid this fate, any state taxing cannabis should include a weight-based tax in their tax regime. The weight, or quantity, of cannabis sold is likely to be far more stable over time than its price. And quantity-based taxes are already common in other types of excise taxes, including those levied on cigarettes, motor fuel, and soda. Alaska, California, and Maine already include a weight-based calculation in their cannabis tax structures.

Looking ahead, it’s clear that cannabis taxes are going to become an increasingly significant component of state and local tax policy. While cannabis taxes alone won’t balance a state or locality’s budget, they can raise meaningful revenue. To do so over the long-run, however, those taxes need to be well-designed.

Read ITEP’s report: Taxing Cannabis