Updated January 12, 2026

Budget-wise, there are two kinds of states: those who have acknowledged the fiscal crater caused by the new Trump tax law and those that have not. Colorado joined the former camp this month, making substantial progress in closing a $750 million hole in the state’s current-year budget during a special legislative session. Among the revenue-raising tax reforms that were approved are two provisions that would more equitably tax the profits of big multinational corporations doing business in Colorado.

One bolsters Colorado’s corporate combined reporting regime by including corporFFate income reported in certain offshore tax havens in Colorado’s potential income tax base.

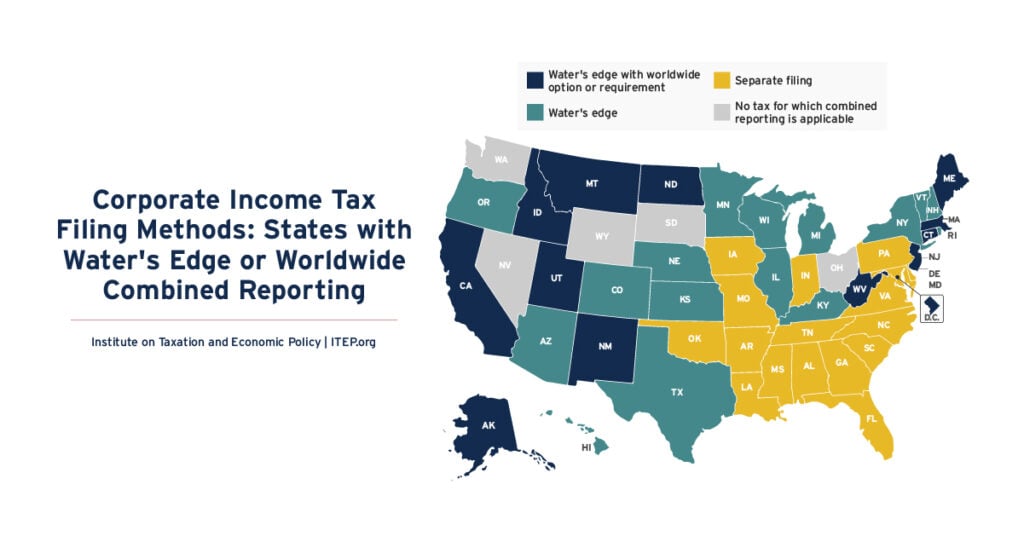

While combined reporting is the most effective single strategy for clamping down on multistate corporate tax avoidance, Colorado and almost all other states employing it use a “water’s edge” variety of combined reporting that can only reach income reported by corporate subsidiaries located within the U.S. This is problematic because, as ITEP and others have documented for years, large multinationals have developed a huge network of foreign subsidiaries into which U.S. income is shifted on paper to avoid paying state and federal income taxes.

While the best approach to ending this offshore tax avoidance is the adoption of worldwide combined reporting (WWCR), which includes all the income of foreign subsidiaries in a company’s potential state tax base, Colorado has been one of a number of states that have taken a more incremental (yet still effective) approach to this problem by adding back income from a “tax haven list” of specified countries that are widely recognized as offshore tax havens.

The main limitation of this approach is that the accepted list of offshore tax havens changes over time and must be modified in response to those changes. This is exactly what the Colorado law enacted this week does, adding Hong Kong, Ireland, Liechtenstein, the Netherlands, and Singapore to its list of known offshore tax havens. Most of the states currently employing combined reporting could easily, and productively, follow Colorado’s lead in this way.

Another eminently sensible corporate tax reform that Colorado lawmakers got over the finish line during the special session is decoupling from the Foreign-Derived Deduction Eligible Income (FDDEI) deduction, previously known as the Foreign-Derived Intangible Income (FDII) deduction.

Like a china cabinet full of old family “heirlooms,” the FDDEI deduction is a useless inheritance that many states have forgotten they were given. Enacted in 2017 and expanded by the recent Trump tax law, the FDDEI deduction was originally designed to encourage multinational corporations to onshore their intellectual property but now operates as a no-strings-attached giveaway to companies that sell products and services to customers in other countries. Because almost every state bases its corporate tax on federal rules, many states automatically adopted the FDDEI deduction starting in 2018 when Congress did so at the federal level.

If the claim that FDDEI encourages onshoring ever had a whiff of plausibility, it was because the FDDEI regime exempted a 10 percent rate of return on U.S.-based assets that contributed to the creation of foreign export sales. This means that corporations can reduce the U.S. tax rate on export sales by locating more of their sales-producing assets to the U.S. – although there is little empirical evidence to suggest that this incentive has had a real-world effect on the location of these assets.

But even when the federal FDDEI deduction could plausibly be described as encouraging repatriation of intellectual property to the U.S., it made little sense for Colorado or other states to adopt it. Any incentive effect of the deduction would have been spurred by the federal-level deduction, not the more trivial add-on effect of a state piggyback deduction. Moreover, intellectual property onshored because of the deduction could as easily go to California or Arizona as Colorado, raising the question of why Colorado lawmakers would want to subsidize onshoring that only benefits other states.

Changes made to the FDDEI deduction by the 2025 Trump tax law, enacted in July, eliminated the 10 percent rate of return exemption, which means that that even its advocates can no longer say with a straight face that FDDEI might encourage onshoring of intellectual property. It’s now a simple export subsidy. All the more reason for Colorado to stop doing so, and for every other state to follow suit.

Colorado lawmakers also acted on another sensible progressive option for reducing the state’s newly-unfolding deficit.

A temporary provision that disallows Colorado’s version of the federal qualified business income deduction for high-income Coloradans was set to expire at the end of 2025; however, HB25B-1001 made this provision permanent, raising close to $50 million a year in a way that would affect only the very wealthiest state residents.

Unfortunately, more work needs to be done over the course of the next legislative session, as roughly $300 million is still projected to be cut from programs and state services. Colorado could decouple from the new tax law’s boost in the itemized deduction SALT cap to $40,000, a move that would also have virtually no impact on low and middle-income Coloradans.

And the newly expanded federal tax breaks for accelerated depreciation and “Opportunity Zones” threaten state revenues in a way that could be avoided by simply decoupling from these federal tax breaks.

Every state faces impending fiscal challenges due to the corrosive effect of the new Trump tax law. Colorado lawmakers are now sensibly facing up to those challenges. As more states inevitably come to grips with the budgetary holes created by the Trump administration, the corporate tax reform strategies pursued by Colorado this week are a sensible template for action.