It’s a heady time for the leaders of America’s biggest tax-avoiding corporations. After years of damaging revelations that they have manipulated our tax system both at home and abroad, Fortune 500 leaders awoke this Wednesday to see that they had been rewarded with the equivalent of a box of chocolates and a bouquet of flowers: this week’s big tax bill slashes the corporate tax rate many of these companies never paid from 35 to 21 percent, while keeping intact many of the unwarranted tax breaks they relied on and creating even more corporate giveaways.

While many Fortune 500 CEO’s likely had to restrain themselves from preemptively shouting “we’re going to Disneyland” in an homage to the Disney Corporation’s trademark ad spot involving the winner of each year’s Super Bowl, it’s pretty understandable that several of them—including known tax avoiders AT&T, Boeing, Comcast and Wells Fargo—would preemptively make grandiose promises that they will reserve part of their tax cuts for the little people who made it all possible.

AT&T and Comcast each announced they will pay a $1,000 bonus to many workers. Boeing pledged to invest $100 million in employee training, and Wells Fargo said it would boost its minimum wage to $15 an hour. Each of these promises appear to have been designed to show that Americans’ worst fears about the new tax plan are unfounded.

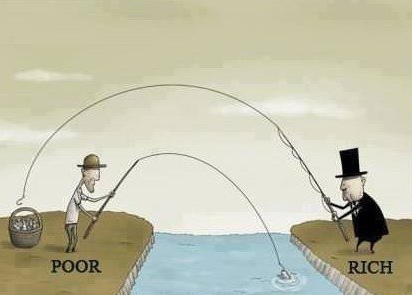

For Wells Fargo, the wage hike and its additional charitable giving represents just 5 percent of the benefit the company is estimated to receive from the tax overhaul. This is the definition of tossing someone a bone.

From a public relations perspective, however, this move is a pretty good idea. When a major tax cut promising at least short-term cuts for middle-income families is the second most unpopular piece of legislation in thirty years, its authors need to spend some time convincing the American public of its merits. And voters are right to be worried: the temporary middle-income tax cuts in this bill, including an expansion of the standard deduction and the child tax credit, will be increasingly offset by inflationary tax hikes over time. And at the end of 2025, every last one of those middle-income tax cuts will expire, leaving only the huge corporate tax cuts as the permanent legacy of the Trump tax plan.

Of course, part of the Trump administration’s sales pitch has been that these corporate tax cuts will trickle down to workers in the form of higher pay, rather than simply feathering the nests of wealthy shareholders. And while it’s certainly plausible that some of the corporate tax cuts will be passed on in this way over the long run, the consensus among economists is that the lion’s share of the corporate cuts will accrue to the owners of these businesses, both in the short term and in the long run. This has been in part demonstrated by the announcement of tens of billions in new share buybacks by companies during the passage of the tax cut bill.

The celebratory announcements made by the companies this week are galling not only because each of these companies have found ways to use our tax system like a piñata, but because each of these highly profitable companies already had at their disposal huge piles of cash that were already available to fund any pay raises, human capital investments or bonuses the companies deemed necessary. After enjoying $20 billion of U.S. profits last year, AT&T was sitting on $5.8 billion of cash and equivalents, a feat that was made possible, in part, by their ability to pay an average federal tax rate of 11 percent over the past decade. Boeing’s equally gaudy ten-year tax rate of 8.8 percent certainly helped the company’s ability to stockpile an even larger $8.8 billion cash warchest. And Wells Fargo’s cool $20 billion in year-end cash could have funded a living wage for its employees long before President Trump prioritized giving the company even more to play with.

This context suggests that these companies could easily have chosen to toss a bone to their workers long before the tax plan’s passage if they had any inclination to do so. Which suggests that the timing of the recent announcements is simply a public relations ploy to convince the public that this tax bill was, against all other evidence, designed with their interests in mind. These companies’ promises also play directly into the President’s own need to claim a victory after a year in which his legislative accomplishments were few and far between. And Trump predictably latched onto AT&T’s announcement as being “because of what we did” with the tax bill. It’s also been widely observed that AT&T in particular has ulterior motives beyond the tax bill for getting in the Administration’s good graces: Trump’s Justice Department has opposed AT&T’s planned merger with Time Warner.

For middle-income workers facing stagnating wages and the continued offshoring of jobs and corporate profits—both trends that the new tax bill will do little to stop and, in the case of offshoring, are likely to encourage—any good news is welcome. The workers who will receive bonuses, pay raises or training as a result of these announcement will be grateful for every penny. But the trail of crumbs these mega-corporations would like us to focus on shouldn’t detract from the big picture: at a time when shoring up middle-income families’ fiscal fortunes should have been the main focus of tax reform, the recently enacted tax bill makes working families an afterthought. And no amount of public relations can change that harsh reality.