Note: This report is adapted from written testimony submitted by Amy Hanauer before testifying in person to the Senate Budget Committee on March 25, 2021.

In 2020, the pandemic killed hundreds of thousands of Americans and unemployment soared to levels not seen since the Bureau of Labor Statistics started collecting data in the 1940s.

Despite that, Amazon’s profits surged to $20 billion last year as people shifted to shopping online. But the company paid just 9.4 percent of its profits in federal corporate income taxes, after paying zero in 2018 and about 1 percent in 2019. Over those three years combined it paid federal corporate income taxes equal to 4.3 percent of its $44.7 billion in profits. That is another way of saying that even though the federal tax rate for corporate profits is 21 percent, Amazon effectively paid a rate of just 4.3 percent during this period.

In 2020, Netflix’s profits surged to $2.8 billion because people went out less and instead watched more TV at home. Yet the company paid less than 1 percent of those profits in federal corporate income taxes, after paying nothing in 2018 and about 1 percent in 2019. Over those three years combined, Netflix paid a total effective rate of 0.4 percent on $5.3 billion in profits.

Even Zoom, the company providing the platform so many people used for meetings and events over the last year, got in on the tax avoidance. Despite an increase in profits of 4,000 percent (not a typo), the company paid no federal corporate income tax on its 2020 profits.[1]

Zoom, Amazon and Netflix are not alone. The pandemic has been hard on many businesses large and small, and many corporations reported losses in 2020. But even those companies reporting profits, which we would expect to pay the corporate income tax, have avoided the tax. Indeed, even some of those who reported record profits because of the pandemic have avoided the tax. So far, ITEP has identified 55 S&P 500 corporations that reported substantial profits in 2020 but also reported paying no federal corporate income taxes that year.[2]

Facts About Corporate Taxes and Corporate Tax Avoidance

Corporate tax avoidance is something lawmakers have known about and failed to correct.

In fact, lawmakers were quite aware of the crisis of corporate tax-dodging when they drafted a major overhaul of the tax code, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), that was signed into law by former President Trump in 2017. Rather than ending tax avoidance by repealing tax loopholes, lawmakers chose to allow this to continue. Tax avoidance by companies like Amazon, Netflix and Zoom are the direct results of the TCJA during the first three years it has been in effect.

When ITEP points out that specific corporations are not paying federal income taxes, representatives of those companies sometimes object that they are following the law. This is an attempt to change the subject. No one is suggesting that large, publicly traded corporations are engaged in clearly illegal activities to evade tax laws. No CEO of a large corporation needs to risk going to prison when Congress has provided so many legal ways for corporations to avoid taxes.

For example, when a company uses the expensing provision enacted as part of the TCJA to deduct the full cost of equipment in the year purchased, that obviously is legal, even if it allows the company to pay nothing at all for several years.

In other words, if Americans are looking for someone to blame for corporate tax dodging, they should mainly look to members of Congress.

This is not to say that all corporate tax avoidance is clearly legal. A great deal of it falls in a legal gray area. Corporations push the envelope and make extremely dubious claims about the nature and locations of their profits and about the tax breaks they are entitled to. Whether a particular practice is legal is an academic point because the question will be determined by whoever controls the relevant information and has the resources to make their case, which is usually a large corporation and not the overburdened IRS.

For example, if a company sells the patent for an invention to its offshore subsidiary for what seems like an artificially low price, and then pays royalties to the offshore subsidiary at what seems like an artificially high rate, the effect is to shift profits offshore. But how often can the IRS prove that the company is doing something wrong?

If the patent is for a new invention (which often happens in the world of tech and pharmaceuticals, for example), the IRS may be hard-pressed to find a comparable transaction between unrelated companies that would prove that something is off about this arrangement.

Instead of asking whether the corporation is doing something illegal, we should ask ourselves how Congress can enact a tax law that can be enforced and that does not create these opportunities for tax avoidance. Further on, this report explains exactly how Congress can accomplish that.

Corporate tax avoidance and low corporate taxes do not help the economy.

Some people might mistakenly think that raising corporate tax revenue—either by ending corporate tax avoidance or in other ways—might harm what seems like a fragile economy. Such concern is not justified.

The corporate income tax is a tax on corporate profits. It does not affect companies that are not profiting and are therefore struggling to survive. Raising revenue by shutting down special breaks and loopholes in the corporate income tax would not affect businesses that are laid low by the pandemic.

Apologists for corporations argue that if corporations pay low taxes, either because the statutory corporate income tax rate is reduced or because of special breaks and loopholes, this has a positive effect on our economy. Conversely, they argue that raising corporate tax revenue, even if only by eliminating special breaks and loopholes, would hurt our weak economy.[3]

But there is no evidence that low corporate taxes help the overall economy. Proponents of the TCJA held out the corporate tax cuts as the key provisions that would spur economic growth. In fact, GDP growth in 2018, the first year the law was in effect, was about 2.9 percent, the same as in 2015. In 2019, the second year the law was in effect, GDP growth was 2.2 percent.[4] (Of course, GDP growth for 2020 was negative.)

American corporations did not appear to be suffering any effects from our tax system even before the TCJA dramatically slashed the corporate tax rate and provided other breaks.

A couple of months before the law was enacted, tax scholar Kimberly Clausing, who now serves as an official in the Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Policy, told Congress that she could not identify any serious problem for American corporations caused by our tax code. She explained that after-tax corporate profits had averaged 9.3 percent over the previous 10 years, compared to 6.2 percent GDP growth over the same period, and American firms accounted for 37 percent of profits and 44 percent of market capitalization of the Forbes Global 2000 companies, even though the United States accounts for just a fifth of the world’s economy. [5] American corporations were never overly burdened by our tax system.

Corporate tax avoidance and low corporate taxes do not make America “competitive” in any sense.

In fact, the corporate tax avoidance allowed by the TCJA weakens the competitiveness of American workers by encouraging American corporations to shift assets and jobs offshore.

Under the TCJA, an American corporation’s offshore profits are not subject to U.S. taxes at all except to the extent that they exceed 10 percent of the company’s tangible assets held abroad. So, a company could shift more tangible assets abroad to reduce the amount of its offshore profits that exceeds that threshold and are subject to US taxes. When a company shifts tangible assets abroad, this means things like factories, offices, equipment—and the jobs that go with all of that—are moving abroad.

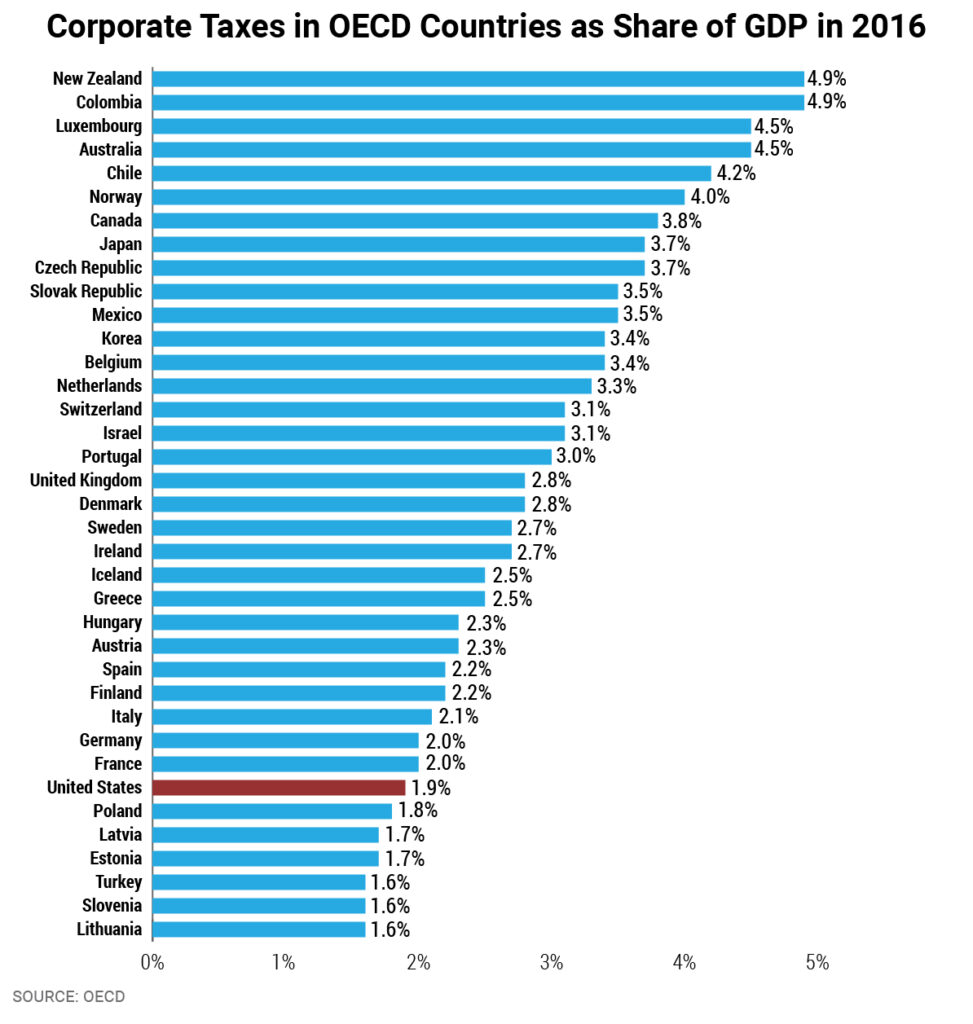

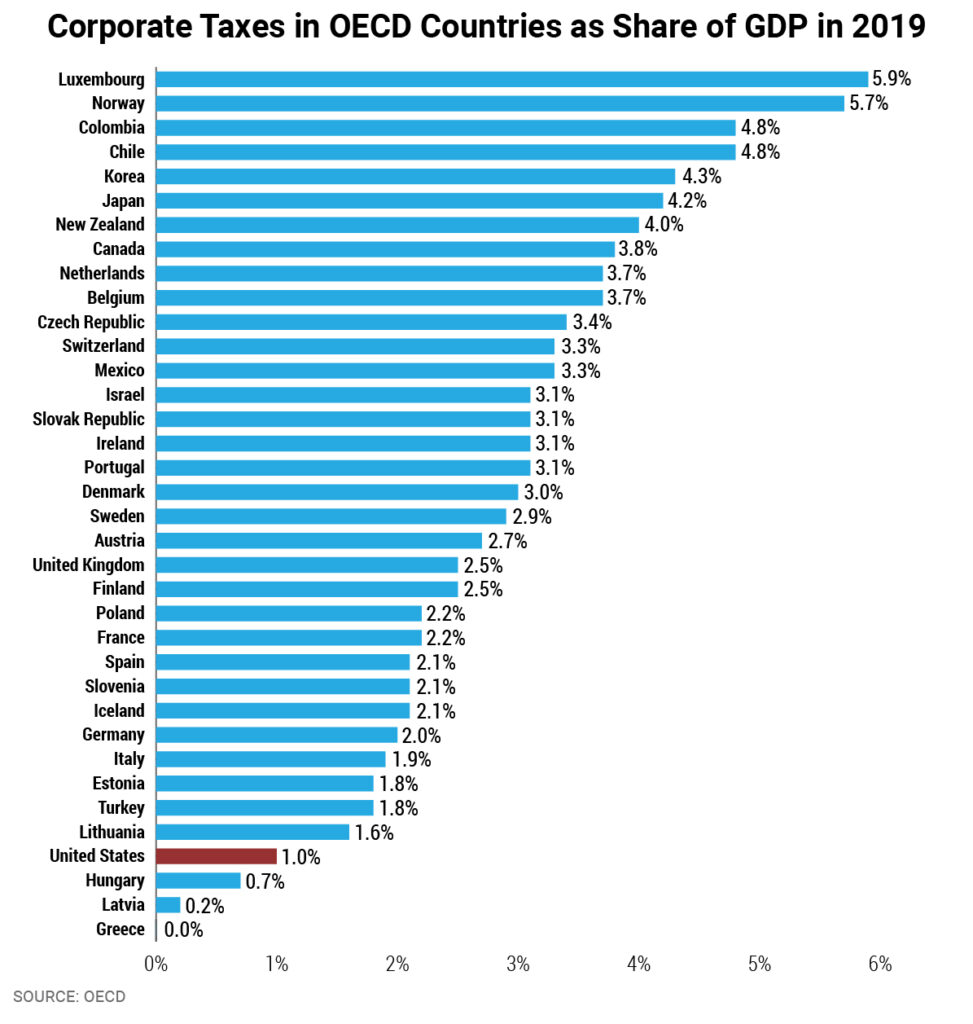

Sometimes when people talk about whether the U.S. corporate tax is “competitive” or “uncompetitive,” they are just talking about whether corporate tax is higher or lower than that of other countries. Our corporate income tax is low compared to other developed countries when measured as a share of our economic output, and this was true even before the TCJA was enacted.

The OECD publishes data annually on 35 to 37 of its member countries, depending on the year and what data is available. In 2016, a year before Congress passed the TCJA, the United States had the seventh lowest corporate tax measured as a share of GDP (as a share of economic output) at just 1.9 percent. By 2019 the United States had fourth lowest corporate tax by this measure, at just 1 percent.

Corporate tax avoidance and low corporate taxes benefit wealthy Americans and foreign investors, not ordinary Americans.

Evidence of the effects of corporate tax cuts indicates that they do not help working people. There is no reason to think that corporate tax avoidance would either.

In addition to slashing the statutory corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, the TCJA also gave corporations a tax break on their offshore cash holdings, which were estimated at the time to be around $3 trillion. Officials in the Trump administration claimed that corporate tax breaks would flow immediately to workers in the form of compensation increases that would average $4,000 to $9,000 annually.

Nothing like this happened. In fact, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) found that corporations generally spent their tax savings (from both the lower rate and from any offshore profits they repatriated) on share buybacks, which are a way of enriching shareholders.[6] Share buybacks reached a record-breaking $1 trillion the year the new law went into effect.

Most economists, including those at the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), believe that most of the corporate income tax is ultimately borne by the owners of corporate stocks and other business assets, as we would expect. Those stocks and assets are owned mostly by the well-off. In other words, the corporate income tax is ultimately borne mostly by the well-off, making it a progressive tax. Conversely, cuts in the corporate income tax and avoidance of the corporate income tax mostly benefit the well-off.

The opposing view, the argument that lower corporate taxes help workers, is based on a speculative theory that lower taxes will result in more investment in American companies, which will increase or enhance equipment and other things that make employees more productive, and this will result in higher wages.

Of course, if any one of these things fails to come true, the whole theory breaks down. After-tax profits of corporations historically have not correlated with investments that enhance productivity, and in any event higher productivity does not always lead to higher wages, particularly in the decades since unionization declined.[7]

And even among economists who believe workers will benefit from a corporate tax cut, most assume that benefit will be small. This is true, for example, of Congress’s official revenue estimators at the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT).

The JCT and the Congressional Budget Office both assume that all the benefits of a corporate tax cut flow to the owners of corporate stocks the first year after it is enacted, but in the long run (which JCT and CBO assume is 10 years) 25 percent of the benefits flow to labor.[8]

Even if this is true (which seems doubtful), it would mean the corporate income tax is a progressive tax even in the long run because three-fourths of the tax is borne by the owners of corporate stocks and other business assets.

In addition to being disproportionately wealthy, many of the owners of these corporate stocks are foreign investors, which means some of the benefits do not flow to Americans at all. In 2013, JCT explained that it believed that 10.8 percent of shares of American corporations were owned by foreign investors.[9] Others find that the foreign-owned fraction is much higher. Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke at the Tax Policy Center estimate that in 2019 foreign investors owned 40 percent of the shares in American corporations.[10]

The bottom line is that corporate tax cuts and corporate tax avoidance benefit high-income Americans and foreign investors, not working people in the United States.

Why This Matters – the Choices Before Congress

Members of the Senate Budget Committee, and members of the Senate and House more broadly, will soon be asked to decide what our nation can afford to do to improve our economy and our health going forward.

Some members of Congress have taken the position that we can afford to preserve the Trump tax cuts for corporations and even expand those tax cuts.

The TCJA includes a tax break, the provision allowing full expensing of capital spending, that is set to phase out starting after 2022 and expire entirely after 2026. The law also includes tax increases that are yet to take effect (amortization of research expenses and tighter limits on deductions for interest expenses). Some lawmakers—including the same lawmakers who drafted this law in the first place—have called for extending the temporary tax break and repealing the tax increases that are soon to take effect.

Some members who hold this position also claim that we cannot afford to help people directly. For example, some take the position that we cannot afford to make permanent the recent expansion of the Child Tax Credit that puts money directly into the hands of families with children and is projected to reduce child poverty by 45 percent.[11]

If Congress must choose how to allocate resources, it would make more sense to direct those resources toward making permanent the Child Tax Credit, which will clearly reduce poverty (by increasing the annual incomes of families with children) instead of directing them to more corporate tax cuts that have speculative benefits for working people that even Congress’s official revenue estimators do not believe in.

This is not to suggest that the ability of Congress to spend money or provide benefits to one group or another is always limited by a need to avoid budget deficits. There are many situations where it makes sense for Congress to spend money or provide benefits without offsetting the cost.

The point, rather, is that the process by which Congress enacts legislation may impose constraints that require lawmakers to prioritize. For example, if the next significant piece of legislation is enacted through the reconciliation process, that process may bar increased deficits or limit any increase in the deficit to a specific amount, so that any additional spending or tax-cutting beyond that amount must be somehow offset.

In this environment, it would make no sense to use up whatever fiscal “space” the reconciliation process provides with more corporate tax cuts. Instead, lawmakers should expand that fiscal space, meaning they should increase the amount of resources at their disposal, by raising corporate tax revenue.

How We Can End Corporate Tax Avoidance and Raise Revenue

End Offshore Corporate Tax Avoidance

It is difficult to document how specific corporations shift profits offshore to avoid taxes because companies are not required to provide country-by-country reporting of their profits and taxes publicly. However, aggregate data show us that American corporations overall claim to earn an impossible amount of their profits in countries with very low corporate taxes or no corporate taxes at all, jurisdictions known as offshore tax havens.

For example, the Cayman Islands has no corporate income tax. It has a population of just 63,000 people, but US corporations claimed to have earned $58.5 billion in profits there in 2017, which was about 10 times the entire gross domestic product (the entire economic output) of that tiny country.[12] This is obviously impossible. Back in 2008, the Government Accountability Office found that nearly 19,000 corporations claimed to be headquartered in a single five-story office building in the Cayman Islands.[13]

The basic problem is that the offshore profits of American corporations are taxed more lightly than their domestic profits. This was true under the old tax law, and it is true under the TCJA, although the details differ. Because corporations pay little in U.S. taxes on their offshore profits, they have an incentive to use accounting gimmicks to make their domestic profits appear to be earned in offshore tax havens. Under the new law, they even have incentives to move real operations, and the jobs that go with them, offshore.

The first goal should be to equalize the U.S. tax rates on domestic and foreign profits of our corporations or come as close as possible to equalizing those rates.

This does not mean that offshore profits would be double-taxed. American corporations would be allowed to claim the foreign tax credit (FTC) for any taxes they pay to foreign governments on their offshore profits, just as they do today. The result would be that our corporations pay at least at the U.S. statutory tax rate regardless of where they claim to earn their profits.

If the U.S. statutory tax rate is 21 percent, American corporations would pay that much on all their profits regardless of whether they are earned in the United States or abroad. For example, if an American company paid foreign taxes on its foreign profits at a rate of 10 percent, it would claim the FTC which allows it to subtract that 10 percent foreign tax from the 21 percent U.S. tax imposed on those profits. It would pay just 11 percent to the United States, which combined with the foreign taxes paid, would come to a rate of 21 percent.

If the company paid foreign taxes at a rate of just 1 percent, it would claim the FTC for that 1 percent and pay the other 20 percent to the United States. For this reason, there would be nothing gained from making profits appear to be earned in an offshore tax haven. The total tax rate paid would be 21 percent no matter where the profits are earned.

The rules established under the TCJA fail entirely to do this. The current rules do not tax offshore profits at all unless they exceed a 10 percent return on offshore tangible assets. In other words, offshore profits equal to 10 percent of the value of the corporation’s tangible assets invested offshore are exempt from U.S. taxes. Tangible assets are what most people think of as “real” investments, such as machines, factories and stores.

The rules simply assume that offshore profits exceeding 10 percent of these assets are profits from other types of assets (intangible assets like patents) that are easier to shift abroad. The rules call these easily shifted profits Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI), which may be subject to tax, depending on whether they have been subject to foreign taxes.

Even when offshore profits are identified as GILTI and subject to U.S. taxes, they are effectively taxed at 10.5 percent, which is just half of the 21 percent imposed on domestic corporate profits. In other words, the TCJA always rewards corporations that can transform U.S. profits into foreign profits, whether this means shifting profits around on paper or moving actual business operations abroad.

There are legislative proposals that would fix this. The No Tax Breaks for Outsourcing Act recently reintroduced by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse and the Corporate Tax Dodging Prevention Act introduced in previous Congresses by Sen. Bernie Sanders would both address this problem. The two bills are different in their technical details, but ultimately both would achieve the goal explained above by ensuring that American corporations pay at least the U.S. statutory tax rate on their profits regardless of whether they claim to earn those profits in the United States or abroad.

During his campaign, President Joe Biden offered a proposal that would partly, but not entirely, achieve the same goal. For example, he would eliminate the exemption that applies to some offshore profits, just like the two bills just mentioned, but he would effectively set the tax rate on foreign profits at three-fourths of the rate on domestic profits. (Biden proposes to raise the overall rate on corporate profits to 28 percent but the rate on offshore profits would effectively be 21 percent.) While this does not go as far as the two bills just described, it would raise hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue and make it far less profitable to shift profits abroad.

Scale Back Depreciation Breaks

Our tax laws generally allow companies to write off their capital investments faster than the assets actually wear out. This “accelerated depreciation” is technically tax deferral, but so long as a company continues to invest, the tax deferral tends to be indefinite. While accelerated depreciation tax breaks have been available for decades, the 2017 tax law provided the most extreme version of accelerated depreciation, allowing companies to immediately write off the entire cost of capital spending. This break, also known as expensing, is scheduled under the 2017 law to be fully in effect through 2022 and then phase out by the end of 2026.

Accelerated depreciation is the reason many companies report paying very little federal corporate income taxes, or none at all, on their profits. In many cases, companies disclose the value of depreciation-related tax breaks, but in other cases, limited financial reporting makes it hard to calculate exactly how much of the tax breaks we identify are related to depreciation.

Even before the 2017 tax bill introduced full expensing, the tax law allowed companies to take much bigger accelerated depreciation write-offs than is economically justified. This subsidy distorts economic behavior by favoring some industries and some investments over others, wastes huge amounts of resources, and has little or no effect in stimulating investment.[14] A report from the Congressional Research Service, reviewing efforts to quantify the impact of depreciation breaks, found that “the studies concluded that accelerated depreciation, in general, is a relatively ineffective tool for stimulating the economy.”[15]

Combined with rules allowing corporations to deduct interest expenses, accelerated depreciation can result in very low, or even negative, tax rates on profits from particular investments. A corporation can borrow money to purchase equipment, deduct the interest expenses on the debt and quickly deduct the cost of the equipment thanks to accelerated depreciation. The total deductions can then make the investments more profitable after-tax than before-tax.

In theory, the 2017 law took steps to prevent this by placing new limits on interest deductions. Unfortunately, these limits would only reduce a fraction of the deductibility of interest, and in fact lawmakers are currently discussing repealing a provision that is scheduled to make these limits stricter after 2022.[16]

Instead of extending or making permanent the expensing provision, Congress should move in the opposite direction and repeal not just the full expensing provision but also some of the permanent accelerated depreciation breaks in the tax code. During his presidential campaign, Sen. Bernie Sanders proposed to do this by “transitioning to economic depreciation for all investments.”[17] This means that the cost of purchasing a piece of equipment, for example, would be written off as the equipment wears out and no sooner.

Eliminate the Break for Stock Options

Most big corporations give their executives (and sometimes other employees) options to buy the company’s stock at a favorable price in the future. Corporations deduct the value of stock options just as they deduct the value of any compensation to employees, but the tax rules make this particular form of compensation a golden opportunity for tax avoidance. The value of stock options is the difference between the agreed-upon price at which the employee can purchase stock and the price at which the stock is selling on the market. For example, if an employee receives options to purchase a certain amount of stock for $1 million and will exercise that option at a time when that amount of stock is selling on the market for $3 million, the value of the options is $2 million.

The problem is that when a corporation deducts that value for tax purposes, they calculate it in a way that generates a much larger figure than the actual cost to the corporation, which they report to investors.

Accounting rules require a company to, at the time a stock option is granted to an employee, estimate the value of that option on the date it will be exercised, which is difficult to predict. Unlike the accounting rules, the tax rules allow the company to wait until the employee exercises the option, which could be several years later, and claim a tax deduction equal to the value of the stock option at that time, which can be much larger than the value reported to investors.[18]

It does not make sense for companies to treat stock options inconsistently for tax purposes versus shareholder-reporting, or “book” purposes.[19]

This stock option book-tax gap is a regulatory anomaly that should be eliminated. A template for this reform already exists in legislation introduced in previous Congresses. Sen. Carl Levin first introduced the bill as the Ending Double Standards for Stock Options Act in 1997 and reintroduced various versions of the bill in subsequent years, including several cosponsored by the late Sen. John McCain.[20],[21]

Create A New Minimum Corporate Tax

Of the tax breaks already described above, those related to offshore tax avoidance are probably the most important in terms of revenue lost, and they require specific legislation to address them.

Other corporate tax breaks, which could be thought of as domestic corporate tax breaks, include accelerated depreciation and the stock options break described above, among others.

Congress should repeal or at least dramatically reform these domestic corporate tax breaks. If lawmakers are unable to come to agreement on that, the next best reform would be to enact a minimum tax that limits the ability of corporations to use these breaks to avoid taxes.

Our federal corporate income tax used to include an alternative minimum tax for corporations, but Congress weakened it severely many years ago before repealing it entirely as part of the 2017 law.

During his campaign, President Biden proposed a much more effective minimum tax for corporations. It would require corporations to pay a minimum tax equal to 15 percent of the profits they report to shareholders and to the public if this is less than what they pay under regular corporate tax rules. This would require profitable companies like Amazon, Netflix and Zoom to pay at least some income taxes no matter how many special breaks or loopholes in the regular tax rules benefit them.

A corporation paying nothing or very little under the regular tax rules would not be able to avoid the minimum tax Biden proposed unless it low-balls the profits that it reports to the public and to potential investors, which companies never want to do because that would make it difficult to attract investment.

In other words, Biden’s proposal balances corporations’ desire to report low profits for tax purposes against their desire to report high profits to potential investors.

One common criticism of Biden’s proposal is that it would limit the effect of tax breaks that Congress enacted to encourage corporations to do things lawmakers believe are beneficial to the economy or to society. This criticism is without merit because most of the “tax incentives” are nothing more than giveaways to corporations that fail to produce such broader benefits for society. For example, as previously explained, accelerated depreciation appears to do little more than reward profitable companies for making investments they would have made anyway.

Enhance Enforcement of Tax Laws by the IRS

While lawmakers may find it difficult to agree on what our tax laws should be, they should at least agree to enforce those tax laws on the books. And yet the IRS is not always able to enforce our tax laws, including corporate tax laws, because of budget cuts and other constraints.

As previously explained, some corporate tax avoidance falls into a legal gray area where the outcome will depend on whether Congress gives the IRS the resources to investigate and litigate—which it has not done in the past decade.

In fact, ITEP has documented cases in which corporations announce publicly that they have made claims on their tax returns that are unlikely to withstand scrutiny by tax authorities, and those tax authorities fail to investigate before the statute of limitation runs out.

When publicly traded corporations publish financial disclosures to investors, they are required to list any tax breaks they claimed that the IRS is likely to deny. (The accounting rules call these “unrecognized tax benefits,” or UTBs.) Corporations are literally announcing breaks they claim that the IRS will probably find to be illegal. And yet, incredibly, corporations in many cases are allowed to keep these tax breaks, simply because the IRS fails to reach a conclusion before the statute of limitations runs out, which can happen in as little as three years.

ITEP recently examined corporate annual financial reports for 2019 and found that five companies—Chevron, Dell, Eli Lilly, ExxonMobil, and General Electric—kept $1 billion in tax breaks that they previously had admitted were unlikely to withstand scrutiny by the IRS or state tax agencies.[22]

For example, as ExxonMobil’s 2019 annual report discloses, the oil giant reduced its (very large) tally of UTBs by $279 million because the statute of limitations had run out on certain tax savings that it took.

The fact that the IRS is failing to follow up on even the most likely cases of law-breaking—cases in which the corporations themselves announce they are doing something that likely will not pass muster—tells us how weak tax enforcement has become.

This result is unsurprising. A July 2020 report from the Congressional Budget Office found that from 2010 through 2018, lawmakers cut the IRS budget by 20 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars, resulting in a 22 percent staff reduction, including 30 percent of the IRS’s enforcement staff.[23] Natasha Sarin and Larry Summers point out that the cuts are even worse than that. When measured as a share of GDP or tax collections, the IRS has been cut 35 percent over the past decade.[24] To undo those funding cuts, they suggest the IRS budget would need to be increased by more than $100 billion over the next decade.

They conclude that this restoration of funding combined with reforms of how the IRS does business (including technology upgrades, for example) would raise more than $1 trillion over the next decade.[25] While most of that revenue would be raised from individual taxpayers, some of it would be raised by allowing the IRS to fully investigate obvious signs of corporations pushing beyond the limits of what the law allows.

Two recent bills introduced in Congress provide a path forward. In February, Rep. Ro Khanna introduced the Stop Corporations and Higher Earners from Avoiding Taxes and Enforce Rules Strictly (CHEATERS) Act, while Rep. Peter DeFazio reintroduced legislation of his from the previous Congress, the IRS Enhancement and Tax Gap Reduction Act. Both would increase audits of millionaires and large corporations and increase IRS funding although they differ on the details. Both would be a huge help and would make our tax code fairer not by changing what anyone owes in taxes but merely by ensuring that corporations and the well-off pay what they owe.

A Note on Businesses That Are Not Required to Pay the Corporate Income Tax

This report has focused on the federal corporate income tax, and therefore has focused on what the tax code calls C corporations, the entities required to pay that tax. But an equally important conversation is how we treat the businesses we call “pass-throughs” because their profits are passed onto their owners and subject to the personal income tax as part of the owners’ personal income. The TCJA included an enormous tax break, a 20 percent deduction for pass-through business income, the new section 199A of the tax code. We have estimated that more than 60 percent of the benefits of this deduction flow to the richest 1 percent of taxpayers.[26]

The rules determining which taxpayers can claim this deduction are extremely complicated and have birthed a cottage industry of tax accountants and lawyers figuring out how to game them.[27] JCT estimates that the deduction costs about $50 billion a year.[28] It is scheduled to expire, along with most of the personal income tax provisions in the TCJA, at the end of 2025.

Congress should not extend or make permanent this provision but should instead repeal it. On the campaign trail, President Biden proposed to phase out this deduction for taxpayers with incomes exceeding $400,000. This should be considered the minimum that lawmakers should do to remove this regressive and inefficient subsidy for well-off business owners from our tax code.

Endnotes

[1] Matthew Gardner, “Zoom Pays $0 in Federal Income Taxes on Pandemic Profits,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, March 19, 2021. https://itep.org/zoom-pays-0-in-federal-income-taxes-on-pandemic-profits/

[2] Matthew Gardner and Steve Wamhoff, ” 55 Corporations Paid $0 in Taxes on 2020 Profits,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, April 2, 2021. https://itep.org/55-profitable-corporations-zero-corporate-tax

[3] Alex Hendrie, “Biden Corporate Tax Hikes Will Send Jobs Overseas,” The Center Square, February 15, 2021. https://www.thecentersquare.com/national/op-ed-biden-corporate-tax-hikes-will-send-jobs-overseas/article_0be4fa3c-6fae-11eb-9092-3b4f757aecc2.html

[4] https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/USA/united-states/gdp-growth-rate

[5] Testimony of Kimberly A. Clausing Before the Senate Committee on Finance, October 3, 2017. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Clausing%20SFC%20Testimony%2010.3.17.pdf

[6] Jane G. Gravelle and Donald J. Marples, “The Economic Effects of the 2017 Tax Revision: Preliminary Observations,” Congressional Research Service, May 22, 2019. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20190522_R45736_8a1214e903ee2b719e00731791d60f26d75d35f4.pdf

[7] Josh Bivens, “Cutting corporate Taxes Will Not Boost American Wages,” Economic Policy Institute, October 25, 2017. https://www.epi.org/publication/cutting-corporate-taxes-will-not-boost-american-wages/

[8] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Modeling the Distribution of Taxes on Business Income,” October 16, 2013, JCX-14-13. https://www.jct.gov/publications/2013/jcx-14-13/

[9] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Modeling the Distribution of Taxes on Business Income,” October 16, 2013, JCX-14-13. https://www.jct.gov/publications/2013/jcx-14-13/

[10] Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke, “Who’s Left to Tax? US Taxation of Corporations and Their Shareholders,” Tax Policy Center, October 27, 2020. https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/Who%E2%80%99s%20Left%20to%20Tax%3F%20US%20Taxation%20of%20Corporations%20and%20Their%20Shareholders-%20Rosenthal%20and%20Burke.pdf

[11] Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Columbia University. 2021. “A Poverty Reduction Analysis of the American Family Act.” Poverty and Social Policy Fact Sheet. https://www.povertycenter.columbia.edu/news-internal/2019/3/5/the-afa-and-child-poverty

[12] Kimberly A. Clausing, “Five Lessons on Profit Shifting from the US Country by Country Data,” Tax Notes Federal. 169(9). 925-940, January 13, 2021. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3736287

[13] Government Accountability Office, “Cayman Islands: Business and Tax Advantages Attract US Persons and Enforcement Challenges Exist,” GAO-08-778, July 24, 2008. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-08-778

[14] Steve Wamhoff and Richard Phillips, “The Failure of Expensing and Other Depreciation Tax Breaks,” November 19, 2018, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/the-failure-of-expensing-and-other-depreciation-tax-breaks/

[15] Gary Guenther, “Section 179 and Bonus Depreciation Expensing Allowances: Current Law, Legislative Proposals in the 112th Congress, and Economic Effects,” Congressional Research Service, September 10, 2012.

[16] For one thing, TCJA’s new limit on interest deductions does not bar companies using full expensing from deducting interest payments altogether. It limits those deductions to 30 percent of adjusted taxable income. Before 2022, the law defines adjusted taxable income as taxable income before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization are subtracted. From 2022 on, TCJA defines adjusted taxable income as a smaller number, which is taxable income before interest and taxes are subtracted (after depreciation and amortization are subtracted). This limit does not apply at all to companies with less than $25 million in gross revenue nor does it apply to some specific types of businesses (farms, real estate, certain types of energy).

[17] https://berniesanders.com/issues/corporate-accountability-and-democracy/

[18] Employees exercising stock options must report the difference between the value of the stock and what they pay for it as wages on their personal income tax returns.

[19] For more, see Elise Bean, Matthew Gardner and Steve Wamhoff, “How Congress Can Stop Corporations from Using Stock Options to Dodge Taxes,” December 10, 2019, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/how-congress-can-stop-corporations-from-using-stock-options-to-dodge-taxes/

[20] See, e.g., Ending Corporate Tax Favors for Stock Options Act, S. 1491 (111th Congress).

[21] A change included in the 2017 law and improved slightly in the American Rescue Plan Act could partly limit the stock options tax break but would not eliminate it. The 2017 law strengthened an existing limit on corporate tax deductions for compensation paid to a company’s top employees in excess of $1 million by removing an exception for so-called “performance-based pay,” which included stock options. The limit on deduction more than $1 million in compensation generally applies to compensation paid to a corporation’s CEO, CFO, and other top three most highly compensated employees (expanded to include the other top eight most highly compensated employees starting in 2027 under American Rescue Plan Act). However, stock options paid before the 2017 law took effect are exempt and still benefit from the exception for “performance-based pay.” In addition, there are employees of corporations with stock options beyond the CEO, CFO and top three or eight employees, and the limits do not affect stock options except insofar as they account for compensation exceeding $1 million.

[22] Matthew Gardner, “An Underfunded IRS Allows Corporations to Get Away with Probably Illegal Tax Dodges,” October 28, 2020, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/an-underfunded-irs-allows-corporations-to-get-away-with-probably-illegal-tax-dodges/

[23] Congressional Budget Office, “Trends in the Internal Revenue Service’s Funding and Enforcement,” July 8, 2020. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56422

[24] Natasha Sarin and Lawrence H. Summers, Understanding the Revenue Potential of Tax Compliance Investment, September 21, 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3695215

[25] Charles O. Rossotti, Natasha Sarin and Lawrence H. Summers, Shrinking the Tax Gap: A Comprehensive Approach, December 15, 2020. https://www.taxnotes.com/featured-analysis/shrinking-tax-gap-comprehensive-approach/2020/11/25/2d7ht

[26] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, The Case For Progressive Revenue Policies, April 12, 2019. https://itep.org/the-case-for-progressive-revenue-policies/

[27] Martin Sullivan, “Economic Analysis: A Dozen Ways to Increase the TCJA Passthrough Benefits,” Tax Notes, April 9, 2018, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes/partnerships-and-other-passthrough-entities/economic-analysis-dozen-ways-increase-tcja-passthrough-benefits/2018/04/09/27y53.

[28] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2020-2024,” page 28, November 5, 2020, JCX-23-20. https://www.jct.gov/publications/2020/jcx-23-20/