Elise Bean, Matthew Gardner and Steve Wamhoff[1][2]

Summary

Corporations often compensate their CEOs and other top employees with stock options, which are contracts allowing the option holder to purchase the company’s stock at a set price (also called a strike price) for a fixed period, often 10 years. These options can become extremely valuable if the market price for the stock rises above the strike price.

The stock option rules in effect today create a problem because they allow corporations to report a much larger expense for this compensation to the IRS than they report to investors. The result is that corporations can report larger profits to investors (thus protecting or driving up the value of their stock) but smaller profits to the IRS (thus driving down their tax liability), undermining the fundamental fairness of the tax system.

This results in a stock option book-tax gap, the difference between how costs are reported on corporate books for financial accounting purposes versus how costs are reported on corporate tax returns for tax purposes. This book-tax gap has enabled corporations like Amazon and Netflix to overstate their stock option expenses to Uncle Sam and, thereby, collectively avoid paying billions of dollars in federal and state income taxes.

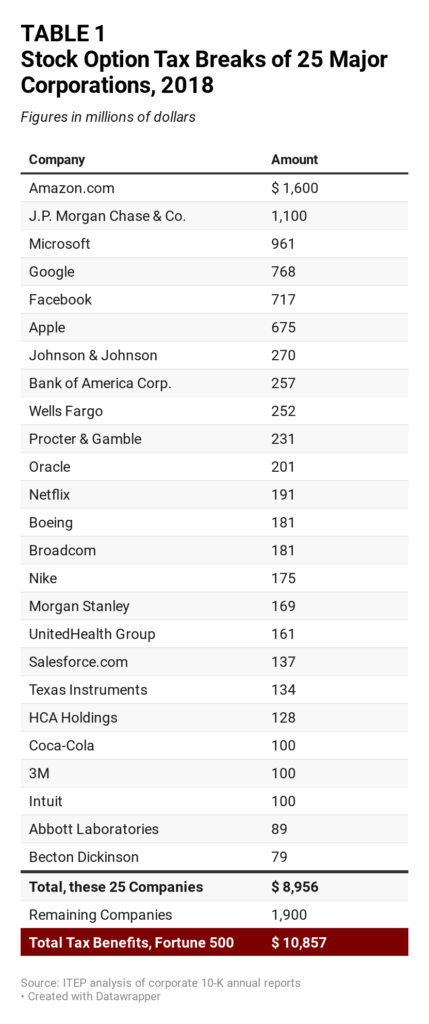

Table 1 lists the 25 corporations disclosing the largest tax breaks from stock options in 2018. The tax break listed for each company is the tax decrease resulting from tax deductions it claimed for stock options in excess of the stock option expenses reported on its books. These 25 corporations collectively received $9 billion in stock option tax breaks in 2018, making up the vast majority of the total $10.9 billion in stock options tax breaks from all the Fortune 500 corporations that disclosed this information.

Giving massive tax deductions to a small number of corporations for handing out stock options to their executives–enabling even extremely profitable corporations to avoid paying taxes–undermines tax fairness, increases public distrust of the tax system, and deprives the U.S. treasury of needed funds. To eliminate the double standards controlling how stock option expenses are reported by corporations to investors versus the IRS, Congress should enact a proposal modeled after the bills introduced in previous Congresses by former Senators Carl Levin and John McCain.

The Book-Tax Gap for Stock Options

In most cases, reporting corporate compensation is straightforward. A corporation reports employee wages and salaries as an expense on its books and in the financial statements made public for investors. The corporation also can claim compensation costs as a business expense on the tax return it files with the IRS, deducting the expense from its taxable income, just as it deducts other expenses.

The problem is that stock options are valued differently under U.S. accounting rules versus U.S. tax rules. For accounting purposes (and in public disclosures to investors), corporations are required to report the cost of stock options on the date they are granted. Companies calculate the value on the grant date using sophisticated formulas which, in part, attempt to predict the market price of the underlying stock when the options will be exercised, which cannot really be known in advance. The value of the options on the grant date for accounting purposes is, therefore, necessarily an estimate. But U.S. accounting rules require this estimate to be included on the corporate books as a compensation expense.

Tax rules, on the other hand, allow a company to wait until stock options are exercised by the employee and use the actual value on the exercise date to calculate the amount of the company’s tax deduction.

If the actual value of the options on the exercise date matched what the corporation reported on its books as the estimated value on the grant date, this timing difference would not be a problem. But in most cases, the value reported for tax purposes far exceeds the estimated value reported for accounting purposes.

In order to report higher profits to investors, corporations typically minimize the estimated stock option expense on their books. When the stock options are later exercised and produce a final value far above the earlier estimated book expense, corporations are happy to report that higher expense on their tax returns and thereby reduce their tax bills.

For example, assume a corporation enters into a contract to allow its CEO to buy one million shares of the company’s stock at any point in the next 10 years at $10 a share. In theory, if the corporation estimates that its share will be worth exactly $10 during the whole 10 years, then it would estimate that the stock options were worth nothing because they would permit the CEO to buy shares at the same price that everyone else pays. More realistically, because share prices tend to increase over time, the corporation could estimate that its stock price will increase to $25 a share.

That means the stock options would allow the CEO to buy one million shares worth $25 million but pay just $10 million. The corporation could, therefore, estimate that the stock options given to the CEO as compensation have a value of $15 million, because that is the expected benefit to the CEO, the difference between what he is allowed to pay for the shares and what they will be worth on the market.

In most cases, however, the corporation does not stop there. It further reduces the estimated value of the stock options to reflect stock price volatility and other factors. Those types of adjustments could reduce the estimated value of the stock options by as much as a third.[3]

So, in this hypothetical scenario, on the grant date (when the corporation grants the options to its CEO), the corporation could record on its books a total stock option compensation expense of just $10 million ($15 million reduced by a third).

When it comes to taxes, however, the corporation would be required by U.S. tax rules to value the stock option compensation cost in an entirely different way. As explained earlier, the company cannot take a tax deduction until the CEO holding the options exercises the right to buy the stock, which in this example occurs 10 years after the options were first granted. On that exercise date, the CEO pays the company $10 million to obtain the underlying stock and then sells the shares on the market. But instead of the expected profit of $15 million, assume the share price has skyrocketed and the CEO sells the shares for a profit of $50 million. The company would then enjoy a windfall tax benefit–it would be able to deduct $50 million from its taxable income, even though it recorded a compensation expense of only $10 million on its books and even though it did not pay any additional money to its CEO, who sold the stock to third parties in the marketplace.

This scenario is not farfetched. In fact, it happens often. IRS data collected by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, chaired at the time by Carl Levin of Michigan, traced the stock option book-tax gap over a five-year period from 2004 to 2009. The IRS determined that profitable U.S. corporations reduced their taxes by billions of dollars each year during the covered period by claiming stock option tax deductions far in excess of the stock option expenses shown on their books. The IRS data disclosed that the total amount of excess stock option tax deductions taken per year by the corporations varied during the covered time period from a low of $12 billion to a high of $61 billion.[4] (These are figures for the excess tax deductions, whereas the figures in Table 1 are for the tax breaks resulting from excess tax deductions.)

The IRS obtained this data from the M-3 information tax returns that large corporations are required to file when they report substantially less income to Uncle Sam in their tax returns than they report to shareholders in their public filings. In many cases, the differences in reported income were due to how stock option compensation expenses were recorded–as a relatively small book expense versus a relatively large tax deduction. Not only that, but once a company reported a large stock option tax deduction, if the corporation did not use all of the deduction to offset its taxable income in that initial year, the tax code allowed the corporation to create a “net operating loss” that the company could continue to use to offset its taxable income over the next 20 years.[5]

Over the years, corporate tax analyses and media reports have identified multiple examples of companies that have used stock options to reduce or even eliminate their taxes. They include companies like Facebook, which claimed the largest known corporate stock option tax deduction when it went public in 2012, estimated at $16 billion;[6] Enron, which used stock option deductions, among other tactics, to avoid paying taxes in four of its last five years;[7] Twitter, which claimed a $154 million tax deduction for a stock option compensation expense which its own books showed cost just $7 million;[8] Netflix, which used an $80 million stock option deduction to avoid paying any taxes on $159 million in 2013 profits;[9] and Amazon, which used stock options and other tax deductions to avoid paying any taxes at all in 2018, despite being one of the most profitable corporations in the world.[10]

As illustrated in Table 1, in 2018, Fortune 500 corporations disclosed a total of $10.9 billion in federal corporate income tax breaks from stock option tax deductions that exceeded their stock option book expenses. Just 25 companies accounted for $9 billion of that total.

These figures are taken from disclosures made by the corporations themselves on their 10-K filings, the annual reports companies are required to file with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to provide information to investors, regulators and the general public. One section of the 10-K requires the corporation to explain, if applicable, why its effective tax rate is lower than the statutory tax rate, including any difference due to “excess tax benefits related to performance-based payments,” which includes differences between the corporation’s stock option book expenses and stock option tax deductions.

Tax breaks for stock options were even larger in years before 2018. In a 2016 report, Citizens for Tax Justice[11] found that the annual combined amount of stock option tax breaks for Fortune 500 corporations ranged from $9.7 billion to $16 billion from 2011 through 2015. The total amount of stock option tax breaks disclosed during that five-year period was $64.6 billion and roughly half, $32.6 billion, was claimed by just 25 corporations.[12]

The amount of stock option tax breaks claimed in each year varies widely for many reasons. The figures depend on how many stock options are granted in a given year and how they are valued on the grant dates; how many highly compensated individuals exercise options during the same year; how stock prices and volatility change at specific companies during the same time period; and whether companies choose to delay using their stock option tax deductions by instead adding them to an outstanding net operating loss. In addition, it is likely that not all corporations report their excess stock option tax breaks every year due to ambiguities and recent changes in the reporting rules.[13]

Perhaps mostly importantly, tax deductions for stock options (like all tax deductions) are worth less for taxpayers facing a lower marginal tax rate. Congress cut the statutory corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent in the tax overhaul enacted at the end of 2017. This could explain why the total tax breaks from stock options in 2018, $10.9 billion, is less than the totals recorded in many earlier years.

The statutory corporate income tax rate of 35 percent that was in effect before 2018 was two-thirds higher than the statutory rate of 21 percent that is in effect today. If the 35 percent rate had been in effect in 2018, the stock option deductions claimed that year could have generated much larger tax breaks.

Today, the U.S. stock market has experienced a series of new highs, suggesting U.S. corporations will continue to benefit from stock option tax windfalls, in which their ultimate stock option tax deductions will far exceed their earlier stock option book expenses. It is time to bring U.S. tax and U.S. accounting rules for stock option expenses into alignment and eliminate conflicting valuation methodologies that enable corporations to report one stock option expense to investors and a completely different expense to Uncle Sam.

The Levin-McCain Proposal to Eliminate the Book-Tax Gap for Stock Options

The stock option book-tax gap (the gap between how stock option costs are reported for accounting purposes versus tax purposes) is a regulatory anomaly that should be eliminated. A template for this reform already exists in legislation introduced by former Senators Carl Levin and John McCain in previous Congresses. Levin first introduced the bill as the Ending Double Standards for Stock Options Act in 1997 and reintroduced various versions of the bill in subsequent years, including several cosponsored by Senator McCain.[14]

If the Levin-McCain proposal had been in effect in the hypothetical described above, the corporation at issue would have reported a $10 million stock option compensation expense for book purposes and deducted the exact same amount from its taxable income in the year when the options were granted. The book expense and tax deduction would have matched. The book expense and the tax deduction would have been taken in the same year. No more valuation gaps, no more timing differences, no more excessive tax deductions.

In contrast, the personal income tax consequences for the CEO would remain the same as under current law, since she would declare the same amount of income when exercising her stock options, no matter how much her employer claimed as a book expense or tax deduction. That is because she earned her income from the stock options that were awarded to her as compensation for her services; the fact that her profit ultimately came from selling the stock to third parties would not change that fact. Thus, she would continue to report $50 million in personal taxable income in the year she exercised the options and sold the underlying stock at great profit to third parties in the market.

Why Some Tax Experts Fail to See the Book-Tax Gap for Stock Options as a Problem

Some tax lawyers and tax accountants have resisted the Levin-McCain solution because they don’t see the status quo tax treatment of stock option compensation as a problem. They are accustomed to an employer deducting the compensation it pays to its employees and having the amount of the employer’s deduction match the amount of taxable income declared by its employees.

That pattern has led some tax lawyers and tax accountants to expect symmetry between an employer’s deduction and an employee’s taxable income. As a result, the current tax treatment of stock options looks normal to these experts: the employer’s stock option deduction matches the employee’s income in the year in which the employee exercises her stock options.

The Levin-McCain proposal confuses these experts because under the senators’ proposal the employee would report $50 million in stock option income while the corporation would deduct just $10 million.

But the confusion arises only because those experts are focusing on the wrong type of symmetry. The relevant symmetry is not between the employer and employee, but between what the employer records on its books as an expense and what it claims on its tax return as an expense. In the case of stock options, that symmetry is completely missing under the current rules. In this example, the corporation recorded a $10 million book expense, but claimed a massively higher $50 million tax deduction. That makes no sense. In fact, there is no other type of compensation in which the tax code allows the tax deduction to exceed the book expense; the two are otherwise always required to match.

It is time to require the same type of symmetry for stock options: the book expense and tax deduction should match. After all, in our example, the $50 million in income to the employee is irrelevant to the compensation cost of the employer, which was reported at $10 million at the time the compensation was awarded to the employee years earlier. The $50 million in income enjoyed by the employee is a combination of the options he received from the company at a below-market strike price plus the stock price increase and outsized profits made from selling the stock in the marketplace.[15]

If the law were changed to ensure that stock option tax deductions equaled—and could not exceed—the expenses shown on the corporate books, corporations might stop minimizing the expense calculated on the stock options’ grant date because that would also minimize the corporation’s tax deduction. The result would be more accurate book expenses, more accurate tax deductions, and fewer discrepancies between the corporate profits reported to investors versus the IRS.

An Alternative Approach: Mark-to-Market Taxation of Stock Options

The Levin-McCain approach is not the only possible solution to the stock option book-tax mismatch. An alternative could make use of the mark-to-market valuation of financial instruments that is gaining greater attention in tax reform efforts. Under this alternate approach, the corporate employer could deduct the cost of the stock options at the time they are granted, matching the cost reported on the corporate books just as in the Levin-McCain proposal. In addition, this approach would require the employee to report taxable income in an equal amount in that same year and then subject the employee’s ongoing stock option holdings to mark-to-market taxation each year until the options are exercised, with any gains or losses taxed as ordinary income.

For example, assume that, in Year 1, a corporation grants an employee options to buy shares at a fixed strike price for the next 10 years, providing compensation estimated to be worth $10 million. Under this alternate proposal, in Year 1 the employer would record $10 million on its books as a compensation expense and deduct $10 million from its income for tax purposes. That same year, the employee would report $10 million in taxable income.

In Year 2, assume the value of the stock rises, and the value of the employee’s stock option holdings increases by $3 million over the previous year. The employer would not be able to claim an increased tax deduction, because the estimated value it recorded on the grant date was designed to take into account future fluctuations in the value of the options. At the same time, because the options actually increased in market value, the employee would report another $3 million in income for Year 2, to be taxed at ordinary rates.

Assume in Year 3, the stock options lose value. The employee would be able to use those losses to offset other taxable income.

Senator Ron Wyden, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee, introduced a bill in the previous Congress called the Modernization of Derivatives Act, which would subject derivatives to mark-to-market taxation and tax the gains at ordinary income tax rates on an annual basis. Stock options are derivatives, since they derive their value from the underlying stock. However, as currently written, the Wyden bill would exempt derivatives that are paid as compensation. A better approach would be to drop that exemption, limit corporate tax deductions for stock option compensation to the value reported on the corporate books in the year the compensation was granted, and tax employees on the ongoing mark-to-market value of their stock option holdings until the options are exercised.

Problems Solved by Ending the Tax-Book Gap for Stock Options

Doing away with the mismatch between what corporations report on their books as an expense and what they deduct as an expense on their tax returns for stock options could solve several problems caused by the existing rules.

First, the current rules encourage corporations to minimize the stock option expenses recorded on their books in order to maximize income, and to grant excessive stock options to their executives in order to take advantage of outsized tax deductions. Requiring corporations to value stock option compensation the same way for accounting and tax purposes would eliminate both distortions.

Second, current stock option tax deductions are very difficult to audit. Senior executives often wait years to exercise their options, making it hard to verify their strike price and grant dates. In addition, they may exercise multiple options that were granted in different years, with different strike prices, creating layers of complexity that make audits time consuming and expensive. Corporate taxes would be simplified if employers had to claim stock option tax deductions in the same years and in the same amounts as the when the stock option expenses appear on the corporate books. It would also make it much harder for corporations to cheat, either by altering strike prices or stock option grant dates, as has happened in the past.[16] The desire to report the lowest possible costs on their books would be balanced against their desire to deduct the largest possible expense for tax purposes.

Third, the current stock option rules create a strange dynamic in which the most profitable corporations generate the largest stock option deductions and consequently pay the least in taxes. A corporation that is more successful than expected will see the value of its stock options rise (because the value of the stock will exceed what was estimated at the time the options were granted) resulting in a larger tax deduction when the options are exercised. The larger deduction means that the better a corporation does, the more stock options will reduce its taxable income, in some cases allowing successful companies to avoid taxes altogether.[17] That dynamic would be eliminated if corporations simply deducted the book expense at the time the options are granted.

Ensuring that corporate stock option tax deductions cannot exceed the expenses reported on the corporate books would remedy an overly generous tax deduction that too many profitable corporations are using to avoid contributing their fair share of taxes.

New Limits on Compensation Tax Deductions Could Help Reduce the Book-Tax Gap

The stock option book-tax problem described here might be somewhat mitigated by a recent legislative change in the tax treatment of compensation.

Under section 162(m) of the tax code, a publicly traded corporation cannot deduct more than $1 million in compensation per employee for its CEO and a handful of other top-paid employees. Until recently this restriction had a very limited impact, however, because it had an exception for performance-based pay, which included stock options.

The Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA), enacted at the end of 2017, eliminated the exception for performance-based pay from section 162(m), which means that, for the first time, the $1 million limit on compensation-related tax deductions applies to stock option pay. This change in the law may limit certain corporate deductions for stock options in the future.

However, TCJA grandfathered stock options that had already been granted at the time it was being drafted, so it may be years before the statutory change has much effect.

In addition, because the revised section 162(m) applies to only a handful of top employees at publicly traded corporations, it will not limit stock option tax deductions at private corporations, will not cover many employees who receive stock option pay at publicly traded corporations, and will not curb tax deductions for stock options valued at less than $1 million per employee. In other words, the stock option book-tax gap will continue to provide profitable corporations with billions of dollars in excessive tax deductions for years to come unless Congress acts.

[1] The authors would like to thank David S. Miller for his help and guidance. Any errors are the responsibility of the authors.

[2] Elise Bean served under Senator Carl Levin of Michigan as staff director and chief counsel for the U.S. Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations until retiring from the Senate at the end of 2014. Matthew Gardner is a Senior Fellow at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). Steve Wamhoff is ITEP’s Director of Federal Tax Policy.

[3] See, e.g., “Stock Option Values: A New Rule of Thumb for Large Caps,” Michael Powers and Mike Meyer, Meridian Compensation Partners (3/6/2018), https://www.meridiancp.com/stock-option-values-new-rule-thumb-large-caps/.

[4] See floor statement by Sen. Levin, “Introducing the Ending Excessive Corporate Deductions for Stock Options Act,” Congressional Record (7/14/2011), page S4616.

[5] See also “Executive Stock Options: Should the Internal Revenue Service and Stockholders be Given Different Information?,” hearing before the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (6/5/2007), S. Hrg. 110-141 (examining stock option book-tax differences at nine publicly traded corporations which, from 2002-2006, collectively reported stock option book expenses of $217 million but took stock option tax deductions totaling $1.2 billion, a book-tax gap of about $1 billion).

[6] See, e.g., “Facebook IPO catches lawmakers’ attention,” Hayley Tsukayama, Washington Post blog (5/17/2012), https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-tech/post/facebook-ipo-catches-lawmakers-attention/2012/05/17/gIQA5veVWU_blog.html.

[7] See, e.g., “Enron Avoided Income Taxes In 4 of 5 Years,” David Cay Johnston, New York Times (1/17/2002), https://www.nytimes.com/2002/01/17/business/enron-s-collapse-the-havens-enron-avoided-income-taxes-in-4-of-5-years.html.

[8] See, e.g., “Senators say Twitter could reap $154 million tax break,” Carolyn Lochhead, San Francisco Chronicle blog (11/6/2013), http://blog.sfgate.com/nov05election/2013/11/06/senators-say-twitter-could-reap-154-million-tax-break/; “IPO shows how Twitter can legally avoid taxes,” Kim Dixon, Politico (11/1/13), http://www.politico.com/story/2013/11/twitter-ipo-taxes-99234.html#ixzz2jgjzCf1k.

[9] See, e.g., “What’s NOT in the Queue for Netflix: A Tax Bill,” Citizens for Tax Justice (2/12/2014), https://www.ctj.org/whats-not-in-the-queue-for-netflix-a-tax-bill/.

[10] See, e.g., “Amazon’s $0 corporate income tax bill last year, explained: The mystery of stock-based compensation,” Matthew Yglesias, Vox (2/20/2019), https://www.vox.com/2019/2/20/18231742/amazon-federal-taxes-zero-corporate-income.

[11] ITEP’s affiliated 501(c)(3) organization, Citizens for Tax Justice formerly conducted research on federal tax policy before ITEP took over that function in 2017.

[12] “Fortune 500 Corporations Used Stock Option Loophole to Avoid $64.6 Billion in Taxes Over the Past Five Years: Apple & Facebook Biggest Beneficiaries,” Citizens for Tax Justice (6/9/2016), https://www.ctj.org/pdf/excessstockoption0416.pdf.

[13]ASC 740, the set of accounting rules written by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) to guide companies in publishing income tax data, requires corporations to disclose “significant” factors affecting effective tax rates, but companies have latitude in interpreting what is “significant.” That latitude may help explain a decline in the number of companies disclosing stock option tax benefits.

[14] See, e.g., Ending Corporate Tax Favors for Stock Options Act, S. 1491 (111th Congress).

[15] The profit made from selling stock after exercising the option is therefore like the carried interest received by fund managers. It is derived from the appreciation of stock but it is clearly compensation for labor.

[16] See, e.g., “Option Backdating and Its Implications,” Jesse M. Fried, 65 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 853 (2008), http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/jfried/option_backdating_and_its_implications.pdf; “What Fraction of Stock Option Grants to Top Executives Have Been Backdated or Manipulated?” Randall A. Heron and Erik Lie, (1/28/2009), https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.1080.0958.

[17] Many economists believe that taxes should be imposed most of all on profits that exceed the normal rate of return, such as economic rents. But the current treatment of stock options creates the exact opposite result by reducing taxes the most for corporations that become far more profitable than expected.