Testimony of Carl Davis, Research Director, Institute On Taxation And Economic Policy

Submitted to: Joint Committee On The Judiciary, Connecticut General Assembly

Senator Winfield, Representative Stafstrom, Senator Kissel, Representative Rebimbas, and Honorable Members of the Judiciary Committee, thank you for the opportunity to submit this written testimony. My name is Carl Davis and I represent the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), a non-profit and non-partisan tax policy research organization. While most of this bill falls outside of ITEP’s area of expertise, we are eager to offer our thoughts on the tax policy aspects of this legislation.

Over the last year and a half, ITEP has conducted extensive research into the rapidly evolving area of state cannabis tax policy. Based on that work, we believe that the tax structure proposed in S.B. 16 is well designed. This testimony explains the advantages of the tax structure proposed in S.B. 16 and offers additional background information as well as potential changes to the bill for consideration.

Weight-Based Tax Adds Stability to Cannabis Tax Structure

One of the most important decisions that must be made in designing a cannabis tax regime is whether to include a tax based on the quantity of cannabis sold (i.e. weight), or to tax exclusively based on price.[1] In addition to taxing cannabis prices through the state general sales tax and the proposed three percent local tax, S.B. 16 also includes a weight-based excise tax. Maine, California, and Alaska also include weight-based taxes in their systems.

Quantity-based taxes are the norm in excise taxation. Every state taxes cigarettes at a flat rate per pack. Every state taxes beer at a per gallon rate, and most states do the same for wine and liquor as well. And every state taxes motor fuel per gallon sold (though some, including Connecticut, levy supplementary motor fuel taxes based on price). In the context of cannabis, weight is the relevant measure of quantity.

The inclusion of a weight-based tax on cannabis in S.B. 16 offers two main benefits relative to taxing exclusively based on price: improved revenue stability and a more effective deterrent effect against harmful consumption.

From other states’ experience with cannabis legalization thus far, it is clear that cannabis prices decline significantly in the early years after legalization is enacted as competition improves, businesses learn to operate more efficiently, and restrictions on the legal market are loosened.[2] Looking ahead, it is inevitable that additional, significant declines in price are yet to come, particularly if the federal government legalizes cannabis or loosens restrictions on the industry.[3]

In an environment of falling prices, a price-based tax will result in automatic tax cuts over time. For instance, if cannabis prices fall from $400 to $300 per ounce, the tax payment required under a 20 percent tax will decline from $80 to $60. This decline in taxes paid per unit sold will exacerbate the decline in cannabis prices and lessen the tax’s deterrent effect against harmful consumption (e.g., consumption by adolescents or excessive consumption by heavy users). It will also negatively impact revenue growth and, in a mature market where quantity sold is not growing significantly from year to year, will lead to a decline in cannabis tax collections.

Weight-based taxes, by contrast, are immune to this type of erosion in their effectiveness as revenue-raisers and as tools for discouraging consumption. Over the long run, quantity sold will be much more stable than cannabis prices. Weight-based taxes are therefore built upon a much more stable base than price-based taxes.

Possible Need for More Taxable Product Categories

The weight-based excise tax in S.B. 16 includes three different tax rates applied to three categories of products:

- Dry cannabis flowers taxed at $1.25 per gram

- Dry cannabis trim taxed at $0.50 per gram

- Wet cannabis taxed at $0.28 per gram

This differentiation between different components of the plant is critical to the effective administration of a weight-based tax since these components vary significantly in both potency and market value. Under this system, the more potent and more valuable flowers are taxed at a higher rate than less potent and less valuable trim (e.g., leaves). Without this differentiation, a low-potency, low-value cannabis plant possessing very few flowers would be subject to the same tax amount as a high-potency, high-value plant containing many flowers.

These categories should be sufficient to administer the tax. California, for instance, administers its weight-based tax using three similar categories: flowers, leaves, and fresh plants.

But other states’ experience with cannabis taxation suggests that S.B. 16 might benefit from adding at least one additional product category to the above list: immature or abnormal flower. The cannabis plant does not always mature in the way that growers hope, and an improperly formed flower can be of much lower value and potency than a properly formed one.[4] To address this reality, the Alaska Department of Revenue recently cut the state’s $50 per ounce tax rate in half, to $25 per ounce, for flower that is “abnormal” or “immature.” Precise definitions are provided in the state’s administrative code, but generally speaking these are flowers that are loose, wispy, or containing seeds.[5] Nevada, which lacks a true weight-based tax but which uses weight-based tax administration techniques, also levies lower taxes on a similar category of product that it labels “small bud.”[6] Adding a comparable product category to S.B. 16 may allow the legislation to better reflect the reality faced by cannabis growers.

There may also come a time when it will be advantageous to create even more product categories. Maine, for instance, has separate categories for seedlings (taxed at $1.50 each) and seeds (taxed at $0.35 each).[7] Colorado, which uses weight-based administration techniques much like in Nevada, has separate categories for immature plants, wet whole plants, seeds, trim allocated for extraction, and bud allocation for extraction.[8] And in addition to the small bud category mentioned above, Nevada also uses categories for wet whole plants, immature plants, pre-rolls, unsalable trim approved for extraction, and unsalable flower approved for extraction.[9]

If the legislature anticipates needing to refine and expand its product category list in the future, it could do so through subsequent legislation or could consider explicitly delegating that authority to the Department of Revenue Services via S.B. 16.

Enforcement of Taxable Product Categories

While there may be some uncertainty around the margins in whether a specific part of the plant should be classified as mature flower, immature flower, or trim, other states’ experience with weight-based taxation thus far has shown that these product categories are clear enough to be administrable without significant difficulty. In the vast majority of cases, flower, trim, and abnormal flower are distinct products that growers can reliably identify.

There remains a possibility, however, that some growers may intentionally miscategorize parts of the plant into the lower-taxed categories in order to lower their tax liability (such as claiming that flower is actually trim, or claiming that a mature flower is actually immature).

Ultimately, regulators will need to determine the most effective means of combatting this form of tax evasion. Based on our conversations with officials in other states, however, there are at least two valuable techniques worth highlighting.

First, there should be an opportunity for whistleblowers to step forward. If employees at cannabis production facilities have a means, and incentive, to report obvious misclassification of plant material then misclassification will be less common.

Second, there should be transparency throughout the supply chain in how any given product was classified and taxed, and there should be penalties for other businesses (distributors or retailers) that knowingly purchase obviously mislabeled and undertaxed products from a supplier.

Inflation’s Impact on Tax Rate Sustainability

While the weight-based tax structure included in this bill will generate more sustainable revenues and deterrent effects than a comparable price-based tax, the lack of inflation indexing weakens the tax on both these fronts.

Generally speaking, writing flat dollar amounts into the tax law is ill advised because those dollar amounts tend to become outdated over time as inflation erodes their real value. Assuming 10 years of two percent inflation, for instance, the $1.25 per gram tax contained in S.B. 16 could see its real value decline by more than 16 percent within a decade. In this scenario, the tax would need to gradually rise to $1.49 per gram over this period to maintain its real value both in the revenues it raises per gram sold, and in the deterrent effect it provides.

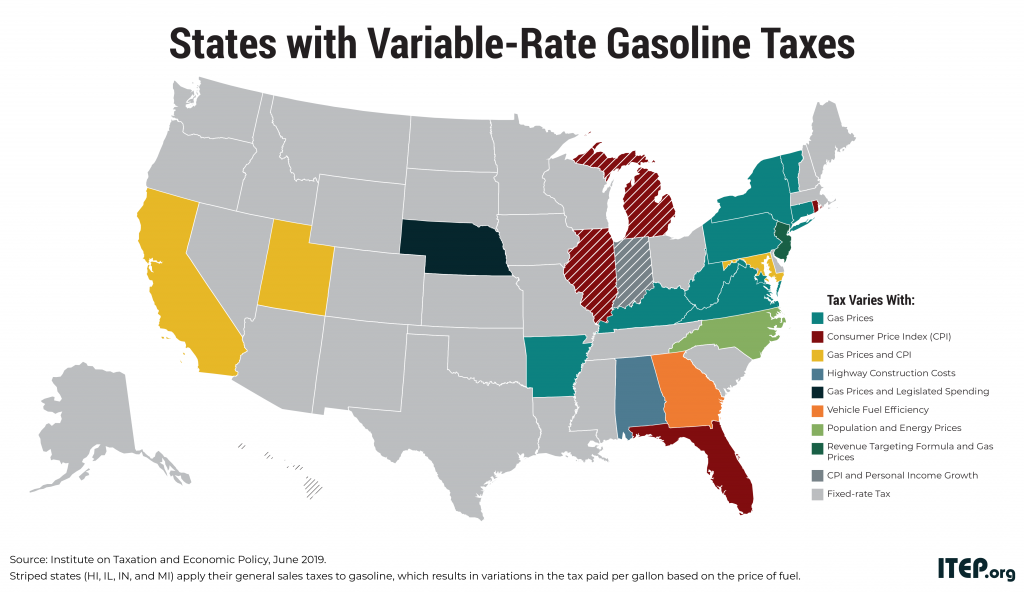

Inflation indexing under state excise taxes is becoming increasingly common. California indexes the weight-based portion of its cannabis tax system to inflation, Minnesota indexes its cigarette tax rate to inflation, and nine states now adjust their motor fuel tax rates for inflation (Alabama, California, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, Rhode Island, and Utah).[10]

In effect, forgoing inflation indexing amounts to a scheduling an automatic cut in the weight-based tax over time. The governor and legislature may have reasons for wanting to schedule such a cut, but we point this out here because such a cut should not be enacted unintentionally or without debate.

Tradeoffs in Medical Cannabis Taxation

Achieving an appropriate tax treatment for medical cannabis requires a careful balancing act. On the one hand, when used appropriately medical cannabis should be beneficial to patients and society and there is therefore little reason to subject this drug to an excise tax that is not applied to other medications. On the other hand, creating a large divergence in effective tax rates applied to medical versus non-medical adult use cannabis can pose administrative difficulties and encourage abuse of the medical designation.

In an environment where any adult can purchase cannabis without a doctor’s recommendation, such recommendations will function much like coupons, entitling the bearer to purchase cannabis without having to pay the same amount of tax as other adults. One risk under such a system is that residents may seek out doctor’s recommendations despite not having a legitimate medical need, and that holders of such recommendations may purchase more cannabis than they need with the intent of reselling the discounted product to their friends, family members, and others.

There are two potential approaches to curbing this problem. The first is to limit the divergence in tax rates between medical and non-medical cannabis, perhaps by subjecting medical cannabis to some, but not all, of the taxes owed on adult use cannabis. S.B. 16 does not take this approach as it exempts medical cannabis from excise and sales taxation entirely. Modifying the bill to tax medical cannabis under the excise tax, but to exempt it from the general sales tax and the three percent local tax, would reduce the incentive for consumers to abuse the medical program while still offering a somewhat lower tax to patients buying medical cannabis. Such a change may also simplify matters for producers as they would not need to determine at harvest time whether the product will be sold for medical purposes (and is therefore tax exempt) or non-medical purposes (and is therefore subject to the weight-based excise tax). When we surveyed state cannabis tax structures last year, we found that fourteen states apply excise taxes to sales of medical cannabis.[11]

If the legislature instead decides that medical cannabis should be subject to a much lower tax rate than non-medical adult use cannabis, or to no tax at all, then it will be necessary to structure and monitor the medical market carefully to discourage abuse of the lower tax rate. This could involve reviewing the list of medical conditions qualifying for discounted cannabis to ensure each condition can be diagnosed by medical professionals with a high degree of certainty, and that there is scientific evidence suggesting that cannabis can be of meaningful assistance in treating that condition. It would also likely involve subjecting medical cannabis to strict purchase limits (such as those that exist for pseudoephedrine, for example) to ensure that patients are not purchasing more cannabis than they need with the intent of reselling the excess.

Income Tax Treatment of the Cannabis Industry, Implications for Advertising

Since 1982, section 280E of the federal tax code has prevented individuals and businesses that are “trafficking in controlled substances” from writing off many of their selling expenses such as rent, utilities, wages, and benefits paid at retail storefronts as well as marketing, legal, and accounting expenses. In other words, they are denied many of the routine business expense deductions that other businesses take for granted. Only the cost of goods sold is deductible.[12]

Because Connecticut bases its own income tax laws in part on the federal code, the state will also deny newly legal cannabis businesses from claiming these deductions on their state income tax returns. If Connecticut legalizes cannabis, there will be a compelling reason for the state to consider extending the same routine tax deductions to legal cannabis sellers that it already extends to other legal businesses. At least some other states with legal sales—including California, Colorado, and Oregon—have already done this by decoupling their tax codes from section 280E.

But while decoupling from section 280E—either in this legislation or in future legislation—has merit, there are at least two potential drawbacks that the legislature may want to address.

The first is that decoupling will negatively impact the state’s income tax revenue collections. In a recent paper evaluating the consequences of section 280E at the federal level, we estimated that the denial of routine business expense deductions has an effect roughly on par with a 6.25 percent tax on retail cannabis sales.[13] Adjusting that figure downward to account for the fact that Connecticut’s income tax rates are much lower than those levied at the federal level, the state tax impact of section 280E could be roughly equivalent to a 1.75 percent retail cannabis tax. If lawmakers wish to decouple from section 280E but are reluctant to cut taxes for the cannabis industry, the excise tax rates proposed in this bill could be increased to achieve a neutral impact on the industry overall.

The second potential drawback associated with decoupling is that doing so will reduce the after-tax cost of advertising for cannabis businesses. If S.B. 16 is enacted as currently written, newly legal cannabis retailers will be allowed to run advertisements but will not be able to deduct the expenses associated with doing so on their federal or state tax returns. The result is that advertising campaigns will more expensive, because of section 280E, than would otherwise be the case.[14]

Legislators may find it appealing to pursue a partial decoupling from section 280E under which employees’ wages, benefits, and potentially other selling expenses would become deductible at the state level, but marketing and advertising would remain nondeductible. Such a design would have the benefit of not creating a new tax incentive to advertise, relative to the status quo.

Conclusion

Thank you again for the opportunity to submit this testimony on the cannabis tax structure envisioned in S.B. 16. We find the tax aspects of this legislation to be well designed and emphasize that the weight-based tax included in the bill will offer a more reliable source of revenue, and a more consistent deterrent effect, than solely applying price-based taxes.

In looking for areas for improvement, legislators may wish to consider adding an additional taxable product category for immature or abnormal bud. There may also be value in reevaluating whether changes should be made to the tax treatment or regulation of medical cannabis to improve enforceability, and whether the flat weight-based tax rates written into the bill should be indexed to inflation. Finally, if lawmakers decide to expand the scope of this legislation—or to enact additional legislation in the future—to grant additional income tax deductions to cannabis businesses, it will be important to keep in mind how those deductions will impact both the state’s income tax revenue collections and the incentive or disincentive effect that the industry faces when deciding whether to run advertising campaigns.

[1] Potency-based taxes are also beginning to receive some consideration, but no state has implemented a true potency tax to date. This is likely because of the perceived difficulty of reliably measuring potency for all product types, especially flower.

[2] Carl Davis et al., “Taxing Cannabis,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Jan. 2019. https://itep.org/taxing-cannabis/.

[3] Carl Davis, “Taxing Cannabis,” Presentation delivered at NASBO’s Annual Meeting, Aug. 7, 2019. https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/aa34f1b2-540e-4f56-b51b-2028c4e92528/UploadedImages/Presentations/AM19_-_Davis.pdf.

[4] Pat Oglesby, “Taxing ‘popcorn bud’ by weight in Nevada,” The Center for New Revenue, Jan. 25, 2019. https://newrevenue.org/2019/01/25/taxing-popcorn-bud-by-weight-in-nevada/.

[5] 15 AAC 61.990. http://www.legis.state.ak.us/basis/aac.asp#15.61.990.

[6] Nevada Department of Taxation, “Fair Market Value of Wholesale Marijuana.” https://tax.nv.gov/uploadedFiles/taxnvgov/Content/Home/Features/Fair%20Market%20Value%20at%20Wholesale%20Summary%20Jan%2020%20(Final%20Draft).pdf.

[7] Federation of Tax Administrators, “State Marijuana/Cannabis Taxes – 2020.” https://www.taxadmin.org/assets/docs/Research/Rates/marijuana.pdf.

[8] Colorado Department of Revenue, “Average Market Rate for Unprocessed Retail Marijuana,” https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/tax/marijuana-AMR.

[9] See note vi.

[10] Carl Davis, “Most Americans Live in States with Variable-Rate Gas Taxes,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Jun. 27, 2019. https://itep.org/most-americans-live-in-states-with-variable-rate-gas-taxes-0419/

[11] See note ii.

[12] Carl Davis, “Cannabis Legalization: Tax Cut or Tax Hike,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Dec. 9, 2019. https://itep.org/cannabis-legalization-tax-cut-or-tax-hike/.

[13] See note xii.

[14] Pat Oglesby, “How Bob Dole got America addicted to marijuana taxes,” Brookings FixGov Blog, Dec. 18, 2015. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2015/12/18/how-bob-dole-got-america-addicted-to-marijuana-taxes/.