An important new book from Professor Dorothy Brown at Emory University offers a timely look at the federal tax code through the lens of racial equity. The Whiteness of Wealth: How the Tax System Impoverishes Black Americans—And How Can We Fix It uses a mix of data, legal scholarship, interviews, and personal stories to tear down the myth that our tax system is neutral with respect to race. Federal tax laws favoring investment income, homeownership, higher education, retirement savings, and marriage systematically advantage white families at the expense of Black families and other people of color. Reforming those policies could advance racial equity, and the Biden administration’s infrastructure and economic recovery legislation that will soon be taken up by Congress represents a chance to begin doing just that.

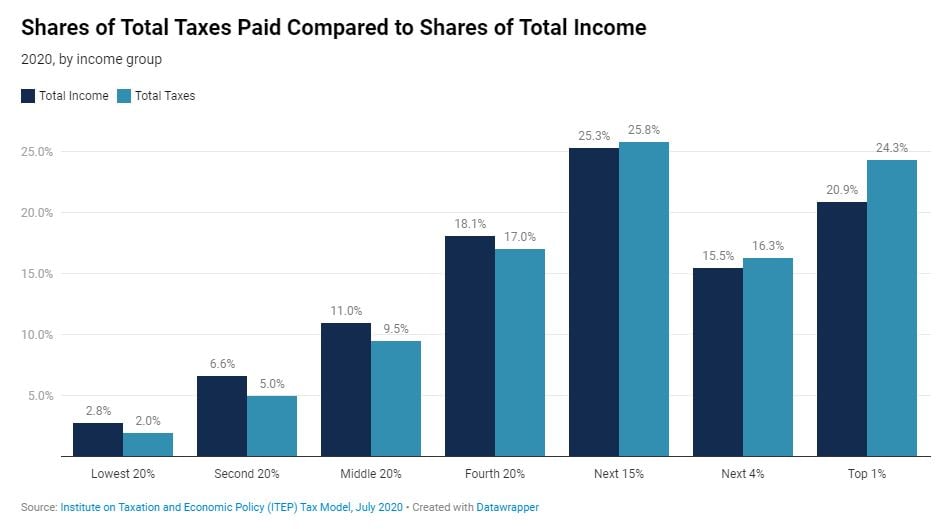

Tax subsidies flowing to high-income earners tend to offer outsized benefits to white families because policy advantage and privilege have ensured that the nation’s top earners are disproportionately white. But income is just the tip of the iceberg. A full understanding of how tax law intersects with racial disparities requires looking not just at the amount of income that shows up on a family’s tax return in any given year, but at their overall wealth – meaning the value of their home, investments, and all the other assets they have accumulated during their lives.

As Brown shows, the federal income tax has preferential treatment of wealth woven throughout. It shows up in the lower tax rates afforded to capital gains income. It shows up in the mortgage interest deduction, property tax deduction, and exclusion of gains on home sales afforded to homeowners. And it shows up in tax-free inheritances and gifts passed down through the generations in families with higher levels of wealth.

Even holding income constant, white families are more likely than Black families to benefit from these provisions because years of racism and discrimination across all segments of society – the housing market, labor market, financial industry, educational systems, criminal justice, and other areas – have prevented people of color from building wealth on the same level as white families.

Two households with the same annual income can be treated differently by the tax code. The one with more wealth, more income from wealth, and more ways to generate wealth – who is more likely to be white – ends up paying less tax.

Relative to a Black family, a white family of the same income level is more likely to own their home, have a higher-valued home that is appreciating more rapidly, access a tax-preferred retirement savings plan through their work, own more financial assets overall, and receive more inheritances, gifts, and other financial support from family members. All these situations tend to reduce federal income tax liability, and all happen to be situations seen more commonly in white households.

The fact that our federal income tax is progressive is immensely important to addressing income inequality – racial or otherwise – because it helps to bring incomes somewhat closer together after taxes. But the tax’s ability to fully address racial wealth inequality, which is an even more daunting problem, is undercut by myriad preferences for the wealthy.

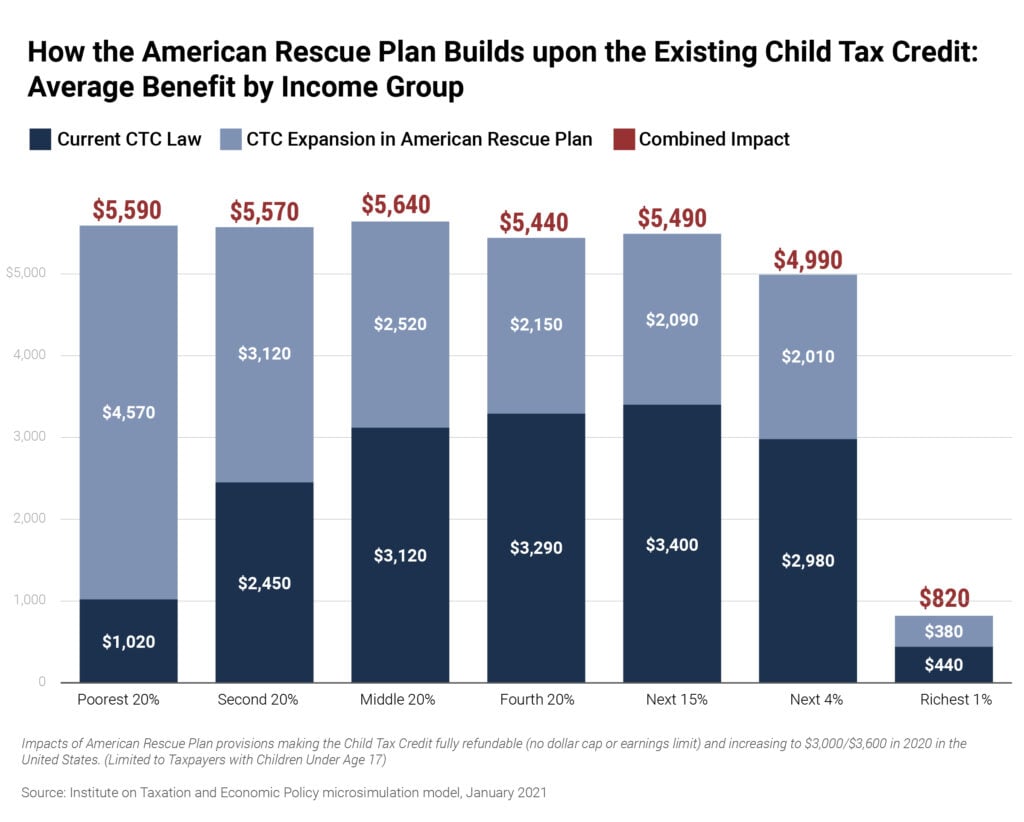

Brown’s preferred approach to dealing with these inequities in the federal tax system is a bold one, a “radical, hold-on-to-your-seat type of change.” She would eliminate virtually all exclusions and deductions aside from a new, refundable living allowance that would exempt a basic amount of income from tax for most families while simultaneously raising the incomes of low-income families up to a level deemed to be a living wage for the geographic area in which they live. She would eliminate the option to file a combined return as a married couple as this primarily benefits one-earner couples who are more likely to be white. And she would offer a tax credit for families of all races with wealth below the national median – a policy that would largely benefit Black families while avoiding any constitutional obstacles to explicitly race-based reparations.

Brown acknowledges that enormous tax reforms of this type will not come easily or quickly. But more modest versions of several of Brown’s preferred reforms are being seriously considered within the Biden administration and Congress.

Most notably, administration officials are reportedly debating taxing realized capital gains income the same as salaries or wages for households with income above $1 million. Ideally, the preferences given to capital gains would be eliminated outright, but President Biden’s campaign pledge not to raise taxes on families earning below $400,000 complicates the issue. Because capital gains income is highly concentrated among the nation’s top earners, either a $400,000 or $1 million starting point for this reform would result in most capital gains being taxed at ordinary rates. This would be a step toward putting workers and investors, and Black families and white families, on a somewhat more even footing.

The administration is also considering ending stepped-up basis, which allows a huge amount of investment income to escape taxation entirely. Stepped-up basis allows wealthy families, most of whom are white, to pass stocks and other property down through the generations without having to pay tax on the income created by those investments. Ordinarily, if a $100,000 investment grows in value to $1 million, the $900,000 gain would be considered taxable income at the time the investment is sold. But if a parent holds onto that investment until death and passes it on to their children, the $900,000 gain is completely tax-free. This outdated tax subsidy has been an active contributor to the nation’s growing wealth inequality. As Brown explains, “white family wealth building has relied on tax policy designed with it in mind.”

The administration is also reportedly leaning toward keeping, for now, the $10,000 cap on state and local tax (SALT) deductions. Repeal of the cap, as is favored by some congressional leaders, would overwhelmingly skew toward high-income white households. In her book, Brown calls for the repeal of all federal tax subsidies for homeownership – including the ability to write-off real estate property taxes under the SALT deduction. Discrimination in government and the mortgage lending industry, together with white homebuyers’ aversion to living in areas with large Black populations, have led to an immensely unequal distribution of real estate property wealth that skews the property tax deduction, mortgage interest deduction, and tax-free treatment of capital gains on home sales heavily in favor of white families. Once again, families with more wealth – be it in their homes or their stock portfolios – end up paying less federal income tax.

Brown’s book ends with an appeal for, among other things, better data to assess the disparate impact of tax policies across race. ITEP recently added this capacity to its model and has begun disaggregating its analyses by race where the data allows. But better official data from the Treasury Department and IRS – which an executive order issued by President Biden in the early days of his presidency seems to require – could open up possibilities for entirely new kinds of analyses.

Brown correctly notes that, when it comes to racial wealth gaps, “Tax policy alone can’t solve the problem. But it can help.” The current federal tax debate represents the perfect opportunity to make progress on this front.