Download National and State-by-State Data

Note: This report, which was originally published in October 2020 when Joe Biden was running for president, has been updated to reflect the most recent economic projections from the Congressional Budget Office.[1]

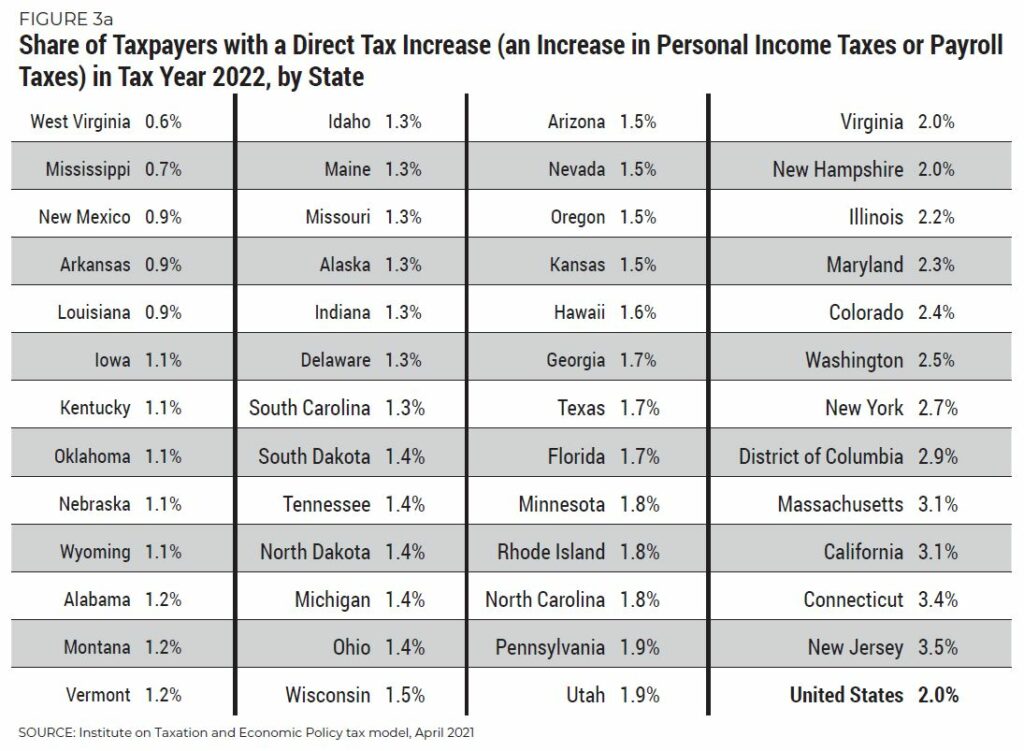

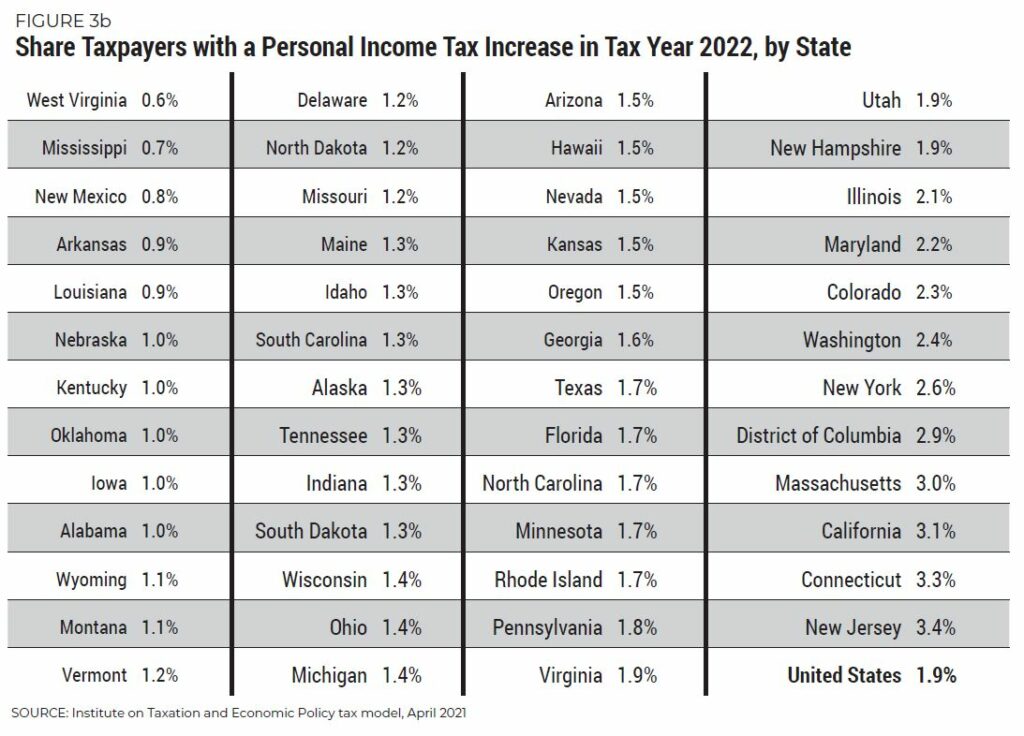

During his presidential campaign, Joe Biden proposed to change the tax code to raise revenue directly from households with income exceeding $400,000. More precisely, Biden proposed to raise personal income taxes on unmarried individuals and married couples with taxable income exceeding $400,000, and he also proposed to raise payroll taxes on individual workers with earnings exceeding $400,000. Just 2 percent of taxpayers would see a direct tax hike (an increase in either personal income taxes, payroll taxes, or both) if Biden’s campaign proposals were in effect in 2022. The share of taxpayers affected in each state would vary from a low of 0.6 percent in West Virginia to a high of 3.5 percent in New Jersey.

This analysis does not include Biden’s proposals that would reduce revenue, which generally benefit those with incomes below $400,000.

Biden’s campaign proposals that would directly raise taxes on households and individuals include:

- Limiting certain tax breaks enacted as part of the 2017 Trump tax law for those with incomes of more than $400,000.

-

- Restoring the personal income tax rates for taxable income exceeding $400,000. Taxable income below $400,000 would continue to be taxed at rates enacted as part of the 2017 law. Taxable income exceeding $400,000, which is now subject to rates of 35 and 37 percent, would be subject to rates of 33, 35 and 39.6 percent as was the case under prior law. [2]

- Restoring the limit on itemized deductions (often called Pease after the lawmaker who initially drafted the provision) for those with taxable income exceeding $400,000. This provision reduces itemized deductions by 3 percent of a taxpayer’s income above a set limit, which under Biden’s plan would be $400,000, but never eliminates more than 80 percent of a taxpayer’s itemized deductions.

- Limiting the 20 percent deduction for certain pass-through business income for those with taxable income exceeding $400,000. Pass-throughs are businesses whose profits are reported on personal tax returns and not subject to the corporate income tax. While proponents of the pass-through deduction describe it as helping small businesses, most of its benefits go to the richest 1 percent.[3]

- For those with taxable income exceeding $1 million, eliminate the special, low personal income tax rate for capital gains and stock dividends, and eliminate the rule that exempts capital gains on assets left to heirs.[4] Currently, capital gains (profits from selling assets) and stock dividends are subject to the personal income tax at much lower rates than other types of income, with a top rate of just 20 percent. Most of the benefits of the special rates for capital gains and dividends go to the richest 1 percent.

- Limit itemized deductions to provide no more than 28 cents in tax savings for each dollar of deductions. Without such a limit, anyone paying a marginal tax rate higher than 28 percent would save more than 28 cents for each dollar of deductions.[5]

- Apply the 12.4 percent Social Security payroll tax to earnings exceeding $400,000. Employees and employers pay the Social Security tax on earnings up to a cap, which is adjusted each year. (In 2022 the cap will likely be $142,800.) This proposal would create a “donut hole” with the payroll tax applying to wages below the cap and above $400,000, but not to wages in between those two thresholds.[6]

In tax year 2022, just 2 percent of taxpayers would face a direct tax increase, meaning an increase in personal income taxes or payroll taxes. Ninety-seven percent of this tax increase would fall on the richest 1 percent, who would see an average increase of $180,770. Virtually all the rest of the tax increase would fall on the next richest 4 percent, as illustrated in Figure 2a below.

Figure 2a shows a minuscule portion of the tax increase falling on taxpayers at lower income levels because the increase in the Social Security payroll tax on earnings in excess of $400,000 can affect taxpayers who also have business losses and therefore technically do not have high incomes.[7]

As illustrated in Figure 2a, the total direct tax increase borne (virtually exclusively by the rich) would come to $301 billion in tax year 2022. However, Table 1 illustrates that the impact on federal revenue would be $216 billion. The difference exists because the revenue impact of the rate increase on capital gains would be reduced by taxpayers’ use of various techniques to avoid the rate increase. ITEP generally follows the approach of Congress’s official revenue estimator, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) in modeling this behavioral response.[8] This analysis also takes into account how this behavioral response would be significantly reduced by Biden’s related proposal to end the exemption for capital gains on assets left to heirs.[9]

The share of taxpayers facing a direct tax increase would vary from a low of 0.6 percent in West Virginia to a high of 3.5 percent in New Jersey.

The five states with the lowest share facing a direct tax increase are West Virginia, Mississippi, New Mexico, Arkansas and Louisiana. Less than 1 percent of taxpayers in all these states would face a direct tax increase in tax year 2022 under Biden’s campaign plan.

The five states with the highest share facing a direct tax increase are New Jersey, Connecticut, California, Massachusetts and New York (or Washington, DC if it is counted as a state).

This result is unsurprising. States with more high-income individuals would have a larger share of residents who pay more under Biden’s plan. But even in the richest states, the share with direct tax increases would be less than 4 percent.

Congress may attempt to enact revenue provisions through the budget reconciliation process in order to pass the legislation with a simple majority in the Senate. In this case, the legislation could include changes to the personal income tax but not changes to the Social Security tax, which are not allowed in reconciliation legislation under Congress’s procedural rules. The appendix includes Figures 1, 2 and 3, which exclude Biden’s proposed change to the Social Security tax, to show only those direct tax increases that can be enacted through reconciliation.

Direct vs Indirect Tax Increases

The focus of this analysis is the Biden campaign plan’s direct tax increases, meaning increases in taxes like the personal income tax and payroll tax that individuals pay directly. The Biden campaign plan also includes several changes to the corporate income tax that would result in indirect tax increases.

The most significant changes, which are included in the infrastructure plan recently put forward by the Biden administration, would raise the rate from 21 percent to 28 percent and limit the tax breaks in the 2017 tax law for profits that American corporations claim to earn offshore.

Under the 2017 tax law, corporate profits are generally subject to a corporate income tax rate of 21 percent. But offshore profits of American corporations are not subject to the federal corporate income tax except to the extent that they are what the law calls global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI), defined as profits earned in a foreign country that exceed 10 percent of the tangible assets the company holds in that country. And even profits identified as GILTI are effectively taxed at just half the rate imposed on domestic profits, meaning they are effectively taxed at 10.5 percent. These rules very likely encourage corporations to shift profits and even real operations and jobs offshore.[10]

Biden would tax all offshore profits (not just the subset of profits defined as GILTI under current law) effectively at three-quarters of the rate imposed on domestic profits. The overall corporate income tax rate under Biden’s plan would be 28 percent, and for offshore profits it would effectively be 21 percent.[11] (Biden proposes other changes for offshore profits that are not included in this analysis.)

These corporate income tax increases could be felt indirectly by individuals at all income levels, but the significant impacts would be felt by the well-off.

While the corporate income tax is paid directly by corporations, economists generally believe that individuals bear the tax in the long run, even if there is some debate over exactly who bears how much of it. Most analysts believe that the bulk of the corporate tax is borne by the owners of corporate stocks and other business assets, which are mostly (but not entirely) owned by well-off individuals. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) assumes that working people eventually bear a quarter of the impact of a corporate tax hike (in the form of a wage reduction), but also assumes that it takes several years for this to happen. Like JCT, ITEP assumes that labor bears none of the cost in the first year that a corporate income tax increase goes into effect. (This analysis focuses on 2022 and assumes Biden’s tax plan goes into effect that year.)

Following JCT’s convention leads us to find that low- and middle-income people indirectly bear a small fraction of the corporate income tax increase in Biden’s plan because they own a small fraction of the U.S. corporate stocks and other business assets.

In 2022, increasing the corporate income tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent would raise $101 billion while limiting the 2017 law’s breaks for offshore profits would raise an additional $40 billion.[12] These changes would therefore increase corporate tax revenue by $141 billion in 2022. However, because foreign investors own roughly 40 percent of the stocks in American corporations, we assume that 40 percent of the corporate tax increase will ultimately be borne by foreign investors, resulting in a corporate increase of $84.3 billion that is borne by Americans.[13]

While Biden proposes several corporate tax changes that ITEP has not analyzed, the two described here are likely to be the most significant.

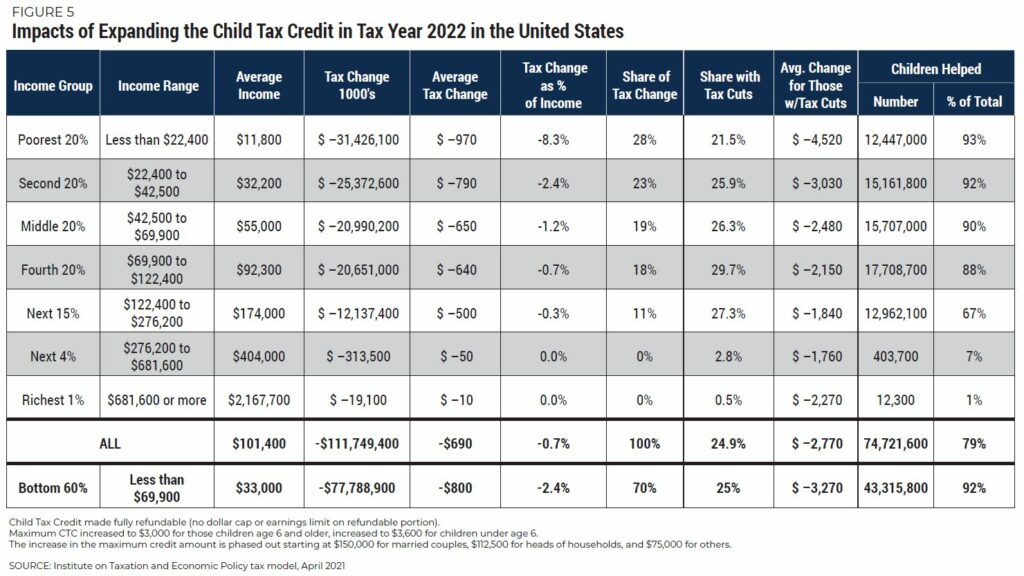

Child Tax Credit Expansion and Other Tax Cuts in Biden Plan Could Offset Most Indirect Tax Increases

The indirect tax increases on low- and middle-income people that result are extremely small and could be offset by tax cuts in Biden’s plan. While ITEP has not analyzed many of the tax cuts that Biden proposed during his campaign, just one of them, Biden’s proposed expansion of the Child Tax Credit, could more than offset any indirect tax increase for many people.

Biden’s campaign proposal to expand the Child Tax Credit (CTC) was enacted, for one year only, as part of the American Recovery Plan Act. The provision makes two important changes to the CTC.

First, it increases the CTC from $2,000 per child to $3,000 per child and provides an additional $600 for each child under age 6. While the CTC generally phases out for married parents with incomes exceeding $400,000 and single parents with incomes exceeding $200,000, this additional $1,000/$1,600 phases out at lower income levels (starting at $150,000 for married parents and $75,000 for single parents).

Second, it removes the two limits that prevent low-income families from receiving the full credit (an overall dollar limit on the refundable portion of the credit and a rule limiting it to a percentage of earnings over $2,500). This is significant because these limits prevent about a third of low- and moderate-income children and families from receiving a full or partial credit.

If the CTC expansion is extended or made permanent, it would benefit households with nearly 75 children in 2022.

As illustrated in Table 5, the expansion of the CTC would more than offset the biggest indirect tax increases that Biden has proposed for all income groups on average except for the richest 5 percent.

The CTC expansion of course only benefits those with children. However, the Biden campaign plan includes many other tax breaks to benefit low- and middle-income people in various stages in life, including childless older workers, first-time homeowners, taxpayers paying off student loans, and people trying to save for retirement, among others.

As already explained, this analysis is incomplete in that it does not include all the provisions in Biden’s campaign plan. This analysis does, however, include all the significant direct tax increases that Biden proposed while running for president. The estimates presented here demonstrate that only the rich would face direct tax increases under Biden’s plan and even the indirect tax increases that he proposes would likely be uncommon or insignificant for most low- and middle-income people.

Appendix

The estimates of Biden’s proposed direct tax increases on individuals in the main section of this report include changes to the personal income tax and a change to the Social Security tax. The figures below include estimates of the proposed personal income tax changes only because these are the proposals that can be enacted through the reconciliation process that Congress may use to pass legislation.

Some of the estimates change very little when the Social Security tax change is excluded. For example, the five states with the largest share of taxpayers affected and the five states with the smallest share affected does not change at all when the Social Security tax change is excluded. The share of taxpayers in each state affected by the personal income tax hikes would vary from a low of 0.6 percent in West Virginia to a high of 3.4 percent in New Jersey.

[1] The numbers in this update are not dramatically different from those in the original version. For example, we now estimate that 2 percent of taxpayers would face a direct tax increase (an increase in personal income taxes or payroll taxes) whereas previously we estimated that 1.9 percent would receive a direct tax increase.

[2] We interpret Biden’s proposal to literally restore the income tax brackets that existed under prior law, with inflation adjustments, for taxable income exceeding $400,000. This would replace the existing 35 and 37 percent brackets with the prior 33, 35 and 39.6 percent brackets for taxable income above that threshold. Overall, this would result in a tax increase for the rich, mainly because the top rate would be restored to 39.6 percent. But a small number of taxpayers would receive a tax cut because of the restoration of the 33 percent bracket affecting some taxable income that is currently subject to the 35 percent rate.

[3] ITEP previously found that in tax year 2019, 64 percent of the benefits of the passthrough deduction went to the richest one percent of taxpayers. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “The Case for Progressive Revenue Policies,” April 12, 2019. https://itep.org/the-case-for-progressive-revenue-policies/#10

[4] Congress’s official revenue estimator, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) assumes that capital gains income is very elastic in its relationship with the tax rate imposed on it. The higher the tax rate on capital gains, the more people with assets will use various techniques to avoid paying the increased rate. One of those techniques is to simply hold onto an asset until the end of one’s life and pass it on to heirs. The tax rules currently exempt any capital gains on assets owned by a taxpayer at the time of death. But Biden’s plan would repeal this tax break as well. Biden’s plan would include unrealized capital gains on assets as taxable income on the final personal income tax return filed for a taxpayer after he or she dies. It is generally assumed that this would be similar to a proposal made by the Obama administration which maintained the exemption for middle-income taxpayers and also exempted assets that a taxpayer leaves to their spouse. This analysis does not include any revenue or distributional impact of taxing gains at death (which is uncertain in the short-run) but takes into account how taxing gains at death would reduce the ability of taxpayers with assets to avoid the rate increase on capital gains.

[5] Under Biden’s plan, there would be four income tax brackets with rates higher than 28 percent: 32, 33, 35 and 39.6 percent. However, Biden says he would raise taxes only for those with income exceeding $400,000. We therefore assume this change applies only to taxable income that would be, in the absence of itemized deductions, in the 33 percent bracket or higher given that the 33 percent bracket applies to taxable income of $400,000 under his plan.

[6] Because the existing cap is adjusted annually but the $400,000 threshold apparently would not be adjusted, the donut hole would eventually disappear. This approach could be thought of as a way to phase an expansion of the payroll tax in very slowly.

[7] For example, in a given year a single taxpayer could have earnings of $450,000 but have capital losses or business losses of $350,000, leaving them with income of just $100,000. This taxpayer would not technically have a very high income but would nonetheless be subject to the payroll tax expansion for earnings exceeding $400,000. Such taxpayers would, however, be rare.

[8] Following the approach of JCT, we take the behavioral response to capital gains tax rate changes into account when estimating revenue impact but not when estimating distribution.

[9] According to a review of JCT’s methods by the Congressional Research Service (CRS), at current tax rates, capital gains income has an elasticity of 0.68 in the long-term. (See “Capital Gains Tax Options: Behavioral Responses and Revenues,” updated May 20, 2020. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R41364.pdf) For a very small rate increase this means that the amount of capital gains income realized will drop by 0.68 times the increase in the tax rate. Revenue raised would therefore be (1-0.68) times the static revenue estimate, or just 32 percent of the static revenue estimates. For a more significant rate increase such as the one Biden proposes, the math is more complicated. It is not entirely clear how much this elasticity would be reduced by taxing gains at death. The Tax Policy Center assumes that taxing gains at death would reduce the elasticity to 0.4. We adopt this assumption for our analysis. JCT assumes that the short-term elasticity for capital gains is even more dramatic than the long-term effect. This analysis uses the long-term elasticity (as reduced by the proposal to tax gains at death) in order to present a more representative example of the likely impact in a typical year.

[10] Steve Wamhoff, “The New International Corporate Tax Rules: Problems and Solutions,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, June 6, 2018. https://itep.org/the-new-international-corporate-tax-rules-problems-and-solutions/

[11] Biden would impose this tax on offshore profits per country rather than globally, as under the current rules. The current global minimum tax allows American corporations to pay less overall.

[12] The effect of the corporate rate increase is calculated by adding the corporate income tax credits, as estimated by JCT, to the corporate tax revenue reported by the Congressional Budget Office and then increasing the amount to reflect the rate increase from 21 percent to 28 percent. The revenue impact of limiting the 2017 law’s breaks for offshore profits are taken from Kimberly Clausing, “Options for International Tax Policy After the TCJA,” Center for American Progress, January 30, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2020/01/30/479956/options-international-tax-policy-tcja/

[13] Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke, “Who’s Left to Tax? US Taxation of Corporations and Their Shareholders,” Tax Policy Center, October 27, 2020. https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/Who%E2%80%99s%20Left%20to%20Tax%3F%20US%20Taxation%20of%20Corporations%20and%20Their%20Shareholders-%20Rosenthal%20and%20Burke.pdf