Millions of families struggled to make ends meet before Covid-19, and they continue to bear the brunt of the pandemic. Low- and moderate-income workers in the earliest days of the crisis lost their jobs at disproportionately higher rates because they did not have the luxury of working from home or they worked in essential or frontline positions where they were more likely to be exposed to the coronavirus.

The Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey provided timely data on the hardships families experienced during the pandemic, but today’s release of the Census Bureau’s Income and Poverty in the United States 2020 gives a more comprehensive picture of how families fared during the first year of the pandemic.

The primary takeaway is that government intervention works.

As anticipated by experts, Census data show that the Official Poverty Measure (OPM) increased from 10.5 percent to 11.4 percent in 2020 due to the pandemic. But government intervention through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act – better known as the CARES Act – resulted in a significant decrease of the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which dropped from 11.8 percent to 9.1 percent in 2020.

The SPM is a more comprehensive measure for evaluating poverty. It considers income, taxes paid, tax credits, safety net programs and cost of living. The Census began publishing the SPM in 2011.

Census data clearly show how government intervention and people-based policies can effectively improve lives even amid a global health crisis and record-breaking unemployment. The CARES Act provided cash payments, included a federal unemployment insurance (UI) boost of $600 per week (and expanded the benefit to gig workers), deferred student debt payments and ensured Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients received maximum benefits. The impact of these policies is visible on both the OPM and SPM. Unemployment benefits, for instance, are counted as income. This means that the 2020 OPM of 11.8 percent would have been significantly higher without the federal expansion of UI benefits. In fact, the Census shows that unemployment benefits kept 5.5 million out of poverty in 2020 compared to just 524,000 in 2019. The SPM also demonstrates the impact of boosting SNAP benefits: 2.8 million people were lifted out of poverty because of SNAP benefits in 2020 compared to 2.6 million in 2019.

While Census data give high-level insights into how the pandemic impacted families in 2020, the real-time impact of these policies through July 2021 is documented by the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University. Its research makes evident that ending the $600 unemployment insurance boost resulted in months of elevated poverty rates across all demographics. These rates dropped significantly as families received their EITC, CTC and stimulus payments.

A Permanent Expansion of the Child Tax Credit is Needed for an Equitable Recovery

Recovery policies after the Great Recession did not invest deeply enough in people and communities and, therefore, class and race-based inequalities worsened. Before the pandemic, Black and Asian household income remained below pre-recession levels, and workers without college degrees continued to experience unemployment at higher levels than before the recession. To ensure a more inclusive recovery, lawmakers should enact policies that center people and prioritize those who were struggling before the pandemic.

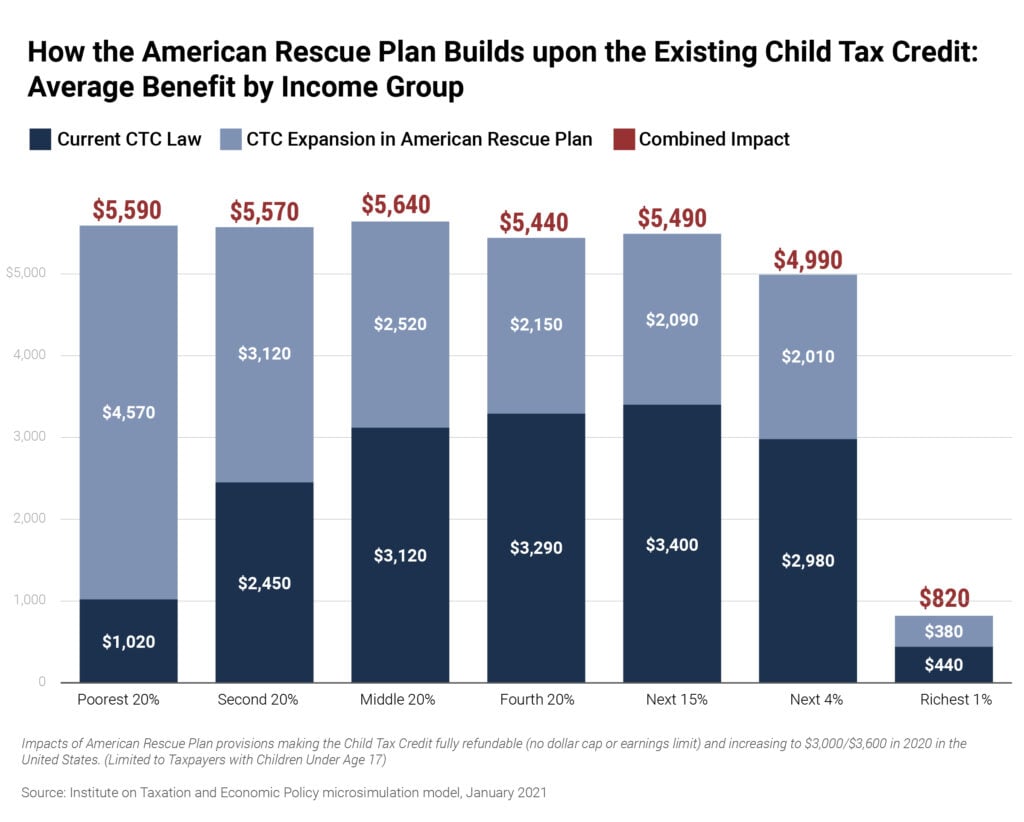

The 2021 American Rescue Plan Act’s (ARPA) expansion of the federal CTC embodies people-centered policies. ARPA increased the credit amount per child from $2,000 to $3,000. Children under age six receive an additional $600. The credit is also now offered in advanced monthly installments of $250 or $300 per child, allowing low- and moderate-income families to keep up with regular expenses like housing, utilities and food. The rescue act made the credit fully refundable, which allows low-income children to receive the full value of the credit, regardless of how little their parents earn.

While the impact of this CTC expansion is not reflected in the 2020 Census data, this expansion is projected to make a huge dent in child poverty. When using the 2018 tax year as a benchmark, researchers found that child poverty could decrease by 40 percent due to the expansion. Making the expansion permanent would bring child poverty under 10 percent in 47 states.

These changes address longstanding inequities by reaching more Black and Hispanic children. If the expansion became permanent, the number of Black children living below the poverty line would be cut in half, and Hispanic children would see a 38% reduction in poverty. Children of all races benefit from the expansion, but children who were historically excluded from the credits’ initial design stand to benefit most. The expanded credit reaches one in three white children and nearly half of Black and Hispanic children.

How Can States Build on this Expansion and Do More to Mitigate Poverty?

Democrats on the Ways and Means Committee have released their plan to extend the CTC expansion through 2025, make the credit permanently refundable and permanently available to immigrant children. This is a huge step in reducing child poverty but cementing the expansion of the increased credit and monthly payments is ideal. While movement on the federal CTC is taking place, this does not mean that states should stay on the sidelines as they are more than equipped to tackle their own inequities through their tax systems. Besides a permanent federal expansion, states should implement CTCs that are structured to strategically tackle poverty in their state. This can be done through a match of the federal credit – similar to the ways in which the majority of states implement matching state-level EITCs – or they can administer a designated amount per child based on a family’s income. Numerous states made gains on CTCs during their 2021 legislative sessions. For instance, bills were filed to create state CTCs in Louisiana and Connecticut. And Colorado funded its state CTC.

While state CTCs are important tools to combat poverty at the state level, they are not the only tool available to legislators. In addition to state Child Tax Credits, legislators should consider:

Property tax circuit breakers: Instead of a homestead exemption, which also benefits wealthy households, states can consider property tax circuit breakers that “shuts off” property taxes after they exceed a percentage of an owner or renters’ income.

Using sales tax credits to help families afford necessities: In addition to replacing a higher reliance on sales tax revenue with less regressive forms of revenue such as progressive income taxes, legislators can provide targeted, refundable sales tax credits. These credits can reduce the regressivity of state tax systems caused by high sales taxes that are paid disproportionately by low- and moderate-income households.

Credits that help families afford childcare: Childcare can eat up large portions of a low- or moderate-income family’s budget. State can provide tax credits to qualifying families with young children that offset the high costs of childcare.

Expanding or creating Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC): States can build on the powerful federal EITC by matching a meaningful portion of the federal credit. States that already have EITCs should look to increase their credits or expand them for low-income workers without children and ITIN filers.

The pre-pandemic status quo failed too many, but it is important to remember that our collective policy decisions shape our outcomes. The status quo was a choice, but the Census data released today shows that different policy choices can create drastically different outcomes for children and families. It is time for our state and federal legislators to put people first when it comes to recovery.