This blog was co-authored by Director of Federal Tax Policy Steve Wamhoff and Federal Policy Analyst Joe Hughes

Business lobbyists are pushing Congress to enact several tax cut “extenders” that benefit their clients before the end of the year. One of these extenders would overturn a stricter limit on tax deductions for interest that companies pay on their debt – a seemingly arcane rule enacted by Republicans as a cost-containing provision in the Trump tax law. Overturning the stricter limit and extending the more generous rule that was previously in effect would help private equity firms maintain their infamous practice of buying companies and loading them up with debt, which often results in the companies spiraling into bankruptcy.

Reversing the Stricter Limit on Interest Deductions Is One of the Big Business Tax Cut “Extenders”

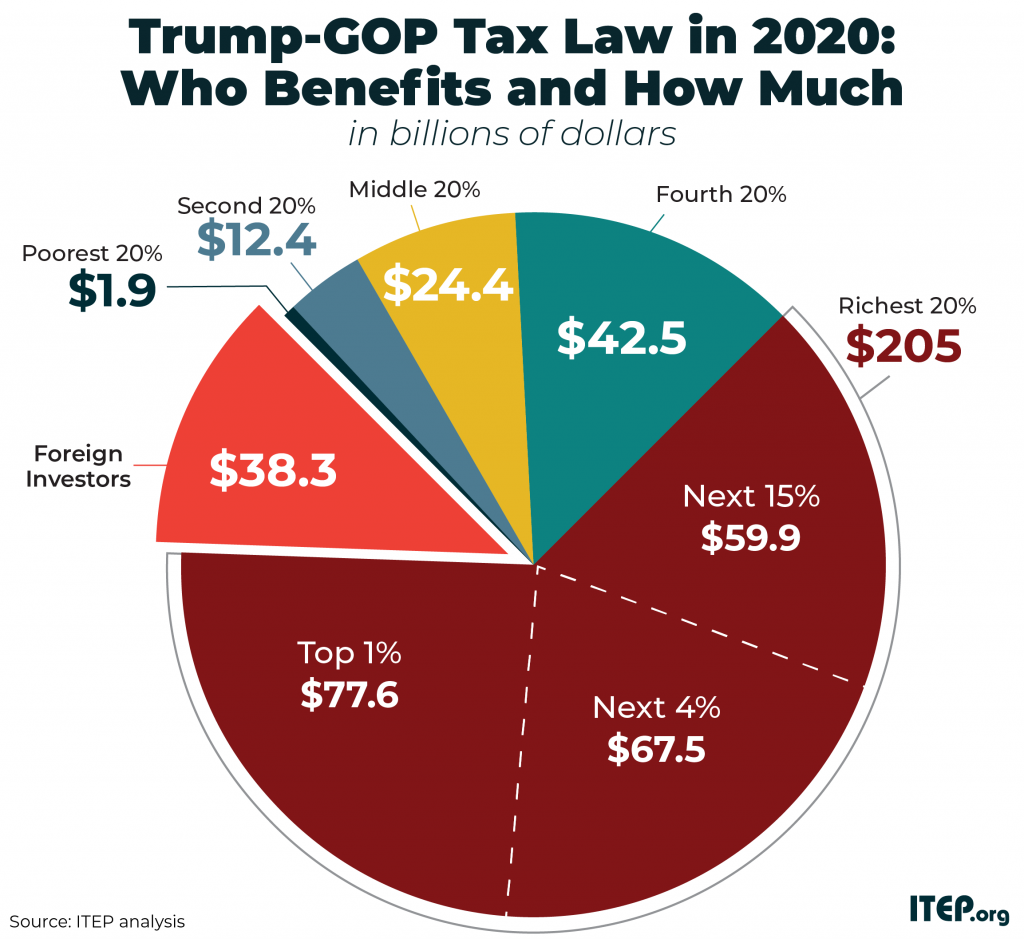

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (the Trump tax law) was overall an enormous tax cut for large businesses and their rich investors. But to make the total cost of the tax cuts smaller over the long term it included cost-containing provisions that were scheduled to take effect in later years.

The claim in 2017 was that these provisions would restrain the cost of Trump’s tax cuts. But now many of the law’s supporters, and some Congressional Democrats, want to repeal or delay the stricter limit on tax deductions for interest. Even if Congress delays the cost-containing provisions for just a year or two, this will likely start a pattern in which Congress does this routinely, meaning they are effectively, if not officially, permanently repealed, adding a huge increase to the final cost of the Trump tax cuts.

The Interest Deduction

When corporations take on debt to finance new investments, they deduct their interest payments from their revenue when they calculate taxable income that they report to the IRS. On the surface, this seems similar to how they deduct other business expenses like rent or payroll when calculating their taxable income.

However, our tax system favors corporate debt over equity, because interest paid to lenders is deductible, but dividends paid to investors is not. When a business needs money, it could either ask investors for funds or it could ask lenders for a loan, and the tax code can distort the decision by favoring the latter.

To prevent overloading businesses with debt, Congress, in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, limited the amount of interest that could be deducted to 30 percent of adjusted income. Through 2021, adjusted income was calculated without reduction for depreciation and amortization. However, beginning in 2022, TCJA tightened the interest deduction substantially: adjusted income is reduced by depreciation and amortization. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimated that reversing the tighter interest limits will cost $200 billion over the next 10 years.

Private Equity’s Pernicious Business Model

Private equity firms have been the worst abusers of overleverage. Private equity firms purchase companies for their investors, taking companies that were publicly traded and making them privately held (hence the term “private equity”). They often load up their acquired companies with debt to help finance the acquisition. And their companies claim disproportionately large amortization deductions from acquisition goodwill.

The idea is supposedly that the private equity managers will improve the performance of their portfolio companies, often by laying off workers, and when successful, they sell the newly efficient, leaner company.

But these companies, after assuming so much debt, often collapse later. It is difficult to believe that this is simply the most efficient outcome, the “invisible hand” of the market doing its work, when in fact our tax code encourages this strategy by favoring debt over equity. Tax law professor Victor Fleischer has written about the problem:

Raising money through equity is less risky because a company can suspend dividend payments when things are tight. It cannot default on interest payments without courting insolvency. And when businesses go bust, shareholders and creditors are not the only ones who get hurt. Employees get axed. Suppliers and customers struggle. Taxpayers pay for bailouts.

Much of this happened when three private equity firms bought Toys “R” Us in 2005 and loaded it up with so much debt that interest payments ate up 97 percent of its profits within a few years. The company filed for bankruptcy in 2017 and closed essentially all of its stores, laying off more than 30,000 workers. Toys “R” Us joined Sears, Payless ShoeSource and many other retailers that were unable to adapt to a changing consumer environment after being weighed down by private equity.

These doomed companies are not alone. A 2019 study found that about 20 percent of large companies acquired by private equity go bankrupt within ten years, compared to just two percent of other large companies.

Extending the Current Rule for Interest Deductions Would Be Another Big Win for Private Equity

Reversing the tighter interest limitation would not be the first tax giveaway for private equity firms this year. Sens. Schumer and Manchin included a provision in the original version of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) that would have partially closed the “carried interest loophole.” This loophole allows private equity fund managers to pay the lower capital gains tax rate on their share of gains when their funds sell companies and other assets. This portion of their compensation is no different than profit sharing or bonuses that are taxed as ordinary income in other industries. But private equity firms call this compensation carried interest and the loophole in the tax code allows them to pay a lower tax rate on it.

At the behest of Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, the provision to limit the carried interest loophole was removed from the final version of the legislation. The provision was estimated to raise $14 billion over ten years. (Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden has a more comprehensive proposal to root out the carried interest loophole that would raise $63 billion over a decade.)

Private equity is doing fine on its own and does not need another tax break. The private equity industry is expected to grow by over 70 percent between 2020 and 2025. The industry’s lobbyists have repeatedly cashed in huge tax favors from Congress. Now they want to go a step further. Congress should keep the stricter limit on deductions for interest payments —one of the few provisions in the 2017 law that asked large businesses to pay a little bit more. There is no reason for Congress to cave to the industry’s lobbyists and overturn this provision now.

We would like to thank Eileen Appelbaum at the Center for Economic and Policy Research and Steve Rosenthal at the Tax Policy Center for their helpful comments. Any errors are our own.